In the 2021 short legislative session, the Kentucky General Assembly will be tasked with crafting a new state budget for 2022. In addition to protecting Kentucky’s existing critical services, there is great need for new state investments to defeat the pandemic and keep people whole through the recession and into a recovery. Although continuing public health and economic crises related to COVID-19, an unclear timeline for vaccinations and uncertainty around federal investments in the economic recovery mean there is much we still do not know about the context for the next budget, we do know that resources will be limited to deal with the enormous challenges in front of us.

To read this preview in PDF format, click here.

Kentucky entered the COVID-19 recession with structural revenue inadequacies that — in combination with an inadequate federal response to the Great Recession — had already led to more than a decade of compounding cuts across budget areas.1 Without significant new resources (which would require a 3/5 vote during a short session), underfunding in schools, family services and more will remain. The harms of continuing to underfund will fall hardest on Kentuckians of color, low-income Kentuckians, people in rural communities and others already facing systemic barriers to economic security.

Budgets are typically created in even-numbered years for two years at a time, but due to uncertainties caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2020 General Assembly passed only a one-year budget. That budget flatlined funding across most areas of investment. Underlying challenges remain unaddressed even as new budget pressures have emerged as the state grapples with COVID-19. Revenue has been shored up thanks to federal aid and some budget holes have been partially filled with CARES Act monies, but much more is needed to fight the virus through a vaccine and support a strong recovery for all Kentuckians regardless of race, class, location and other demographics.

The General Assembly will be crafting a budget in a damaged and uncertain economy

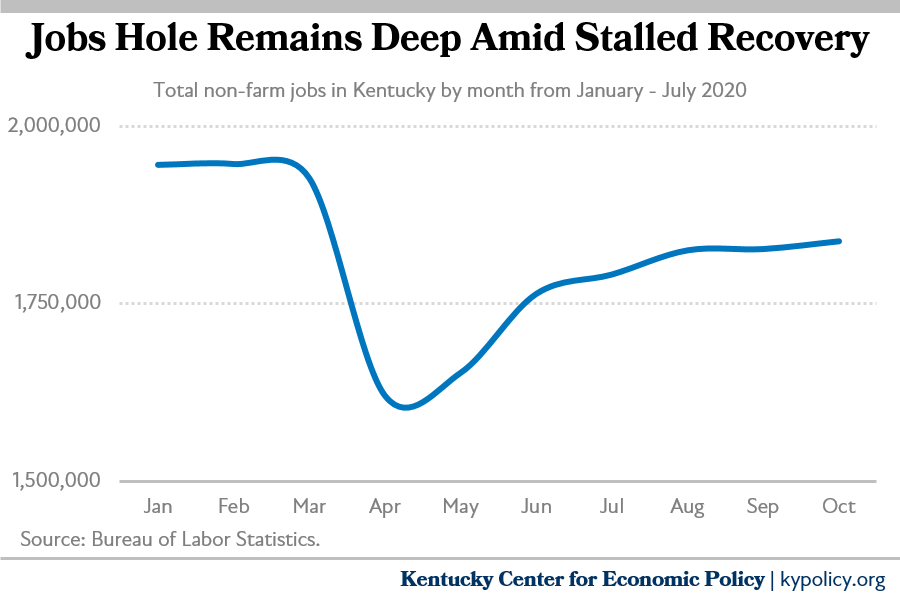

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a deep toll on the nation’s economy, and Kentucky is no exception. Between February (before cases were recorded in Kentucky) and April, Kentucky employment fell by over 326,000, or 16.8%.2 At the same time, claims for unemployment insurance (UI) surged like never before, with initial filers rising from an average of around 3,000 per week to over 100,0000 per week during the month of April.3 According to weekly Census data collected during the pandemic, 45.1% of Kentucky adults who responded reported a loss of employment income in their household between March 13 and November 23.4

What job recovery we have experienced since the worst point of the crisis has been inadequate, and the recovery has slowed in recent months. As of October, 1 in 8 Kentucky workers remained unemployed.5 The economic damage from the pandemic will also continue to be felt for years to come — in wages and employment, but also in reduced public revenue growth. National economic projections estimate that the recovery will continue, but slowly, over the next two years.6

With surging cases of COVID-19, it is unlikely the recovery will accelerate in the short-term, and could even backtrack, until the pandemic is under control and new cases fall significantly. In April, when the bulk of the job losses occurred, consumer spending plummeted, and the freefall was halted only after the federal CARES Act provided billions in stimulus in Kentucky through boosted unemployment benefits, stimulus checks and other forms of assistance.7 As a result, General Fund revenues were not as badly affected as initially predicted; however, without additional federal aid to stimulate the economy, Kentucky will likely face a drop in public revenue as the economy weakens.8

Education faces new budget pressures due to COVID-19 with past underfunding unaddressed

As in other areas, the 2021 spending plan that passed the General Assembly was a continuation budget for P-12 and higher education. There were no new cuts, but education funding fell further behind because there was no new funding to address inflation or reverse prior cuts that have been made for more than a decade. Federal aid through the CARES Act has helped some, but additional needs are mounting in the context of COVID-19.

P-12 education

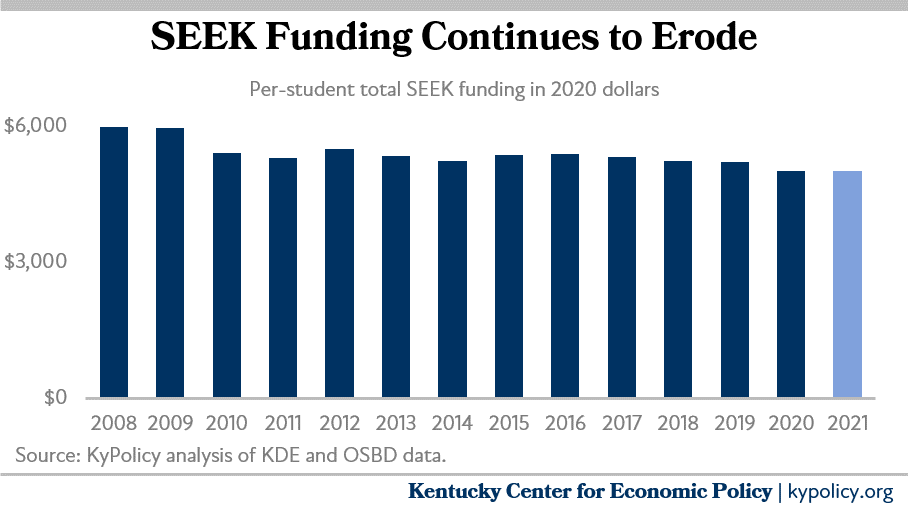

Funding for local schools through the SEEK (Support Education Excellence in Kentucky) formula remained stagnant in the 2021 budget, which means that when compared to 2008 funding levels, the state is spending 16.2% less per student when inflation is taken into account, as shown in the graph below.9 Kentucky was already 4th-worst among states for per-pupil cuts in core funding since 2008.10 These per-student, inflation-adjusted cuts have caused districts to make reductions to staff, course offerings, school-based services and more.11

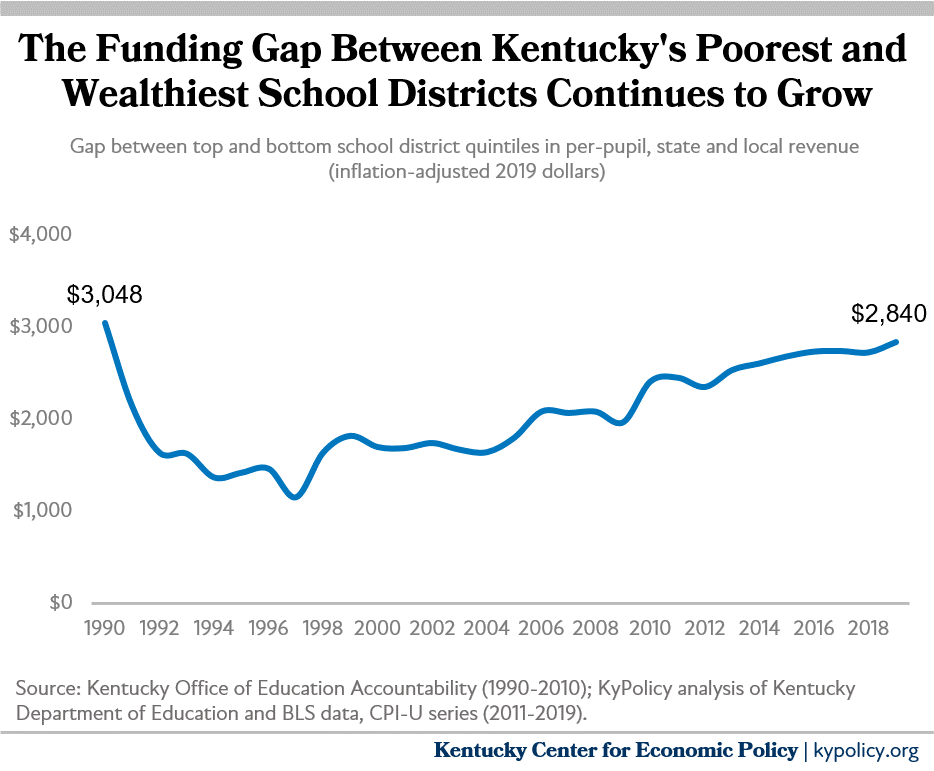

Without additional state funding for SEEK in 2021, the funding gap between Kentucky’s poorest and wealthiest school districts continues to grow. These inequities are almost as pronounced as they were prior to the 1990 passage of the Kentucky Education Reform Act (KERA), which addressed the state’s unconstitutionally inequitable school funding by creating SEEK. The SEEK formula is designed to distribute funding in an equitable way by providing more state funds to poorer districts that are less able to raise local dollars with equivalent effort due to lower property tax bases, and setting an upper limit on the amount wealthier districts can raise to prevent the gap from growing too large. However, because the amount the state contributes under the formula has not been sufficient, local districts have needed to raise more revenues, and with wealthier districts having more capacity to do so, that gap has widened significantly. As a result, wealthy districts had $2,840 more in state and local revenue per student than poor districts in the 2019 school year (the most recent for which data is available).12 The gap increased $122 in 2019 compared to the prior year, and is now just $208 shy of the pre-KERA gap in inflation-adjusted terms.

Non-SEEK learning support services were also largely flatlined in 2021, which means that teacher professional development and instructional resources received no funding, and preschool funding did not increase. Family Resource and Youth Services Centers (FRYSCs) — which provide services for families in schools where at least 20% of students are eligible for free and reduced-price lunches — also received flatlined funding in 2021, resulting in spending that is 14.8% lower than what the state invested in FRYSCs in 2008 in inflation-adjusted terms.13 This funding level is particularly concerning given the need for services such as those provided by FRYSCs have increased during the pandemic.

In addition to the continuation budget not addressing the inadequate funding of P-12 education in Kentucky, there have been and will be new costs associated with safely providing public education to Kentucky families for the near future — whether it’s in person, virtually or a combination of the two. School districts have invested in Chromebooks for students to be able to access their classrooms online, as well as stocking up on masks, disinfectant and deep-cleaning over the summer, among other safety measures. Fortunately federal CARES Act funds specifically for schools (a total of $203.9 million for Kentucky) have been available to mitigate some of these costs; however, the financial impacts of COVID-19 on school districts are continuing to rise.14

Higher education

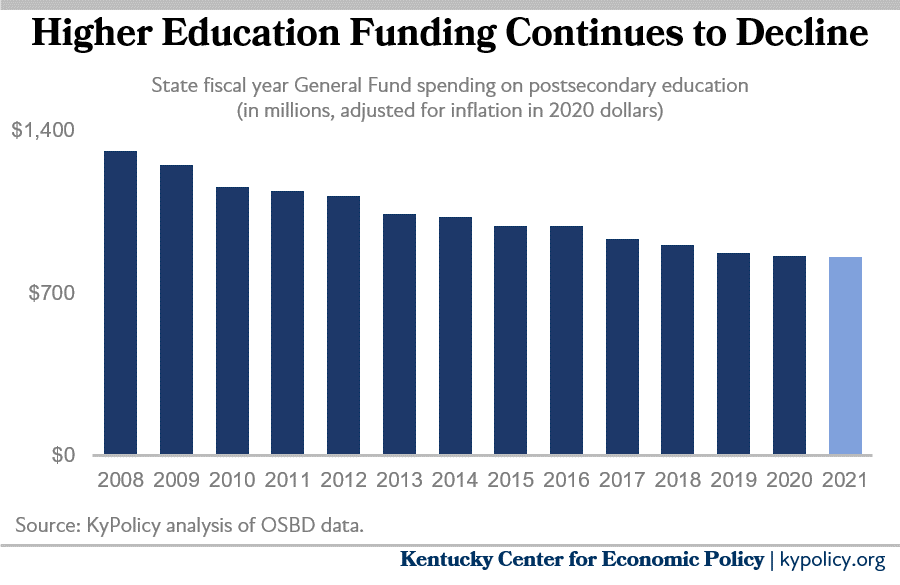

State funding for higher education in 2021 continued at 2020 levels, which is 34.7% lower than state funding for the state’s public universities and community colleges in 2008 once inflation is taken into account, as shown in the graph below.

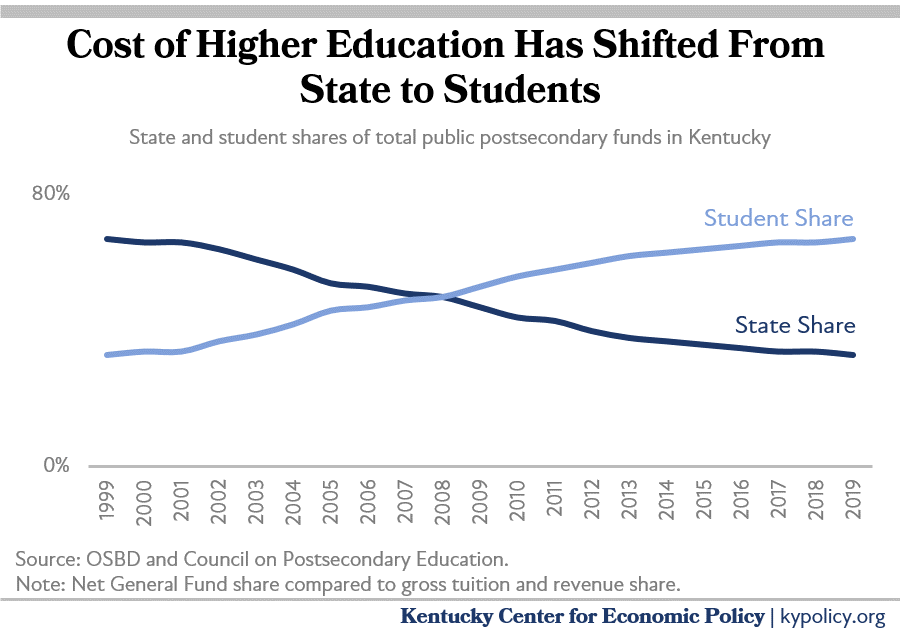

While just a few of Kentucky’s public postsecondary institutions increased tuition this year — and those that did implemented very modest increases — without additional investment the trend of higher education costs shifting from the state to students, as shown in the graph below, will continue into the next budget year.

Approximately $71.2 million in federal CARES Act funds were provided to Kentucky’s public institutions (with an additional $54.6 million going to students attending these universities and community colleges).15 However, according to the Council on Postsecondary Education, the CARES Act funds only covered about a quarter of the additional COVID-19 related costs and forgone revenues caused by the transition to online classes, housing and dining refunds and fewer students enrolling, among other causes.

In addition, approximately 2% of the funds appropriated to public universities in 2021 were in a “performance funding pool,” distributed according to a formula through which small schools and those serving more students with low incomes and students of color are disadvantaged. As a result, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University and 6 of the state’s 16 community colleges experienced a funding cut in 2021 because they did not receive any performance funds.16

Looking ahead to 2022, all state funds for public higher education institutions will run through the performance funding formula unless the legislature takes action, which would mean even deeper cuts for the institutions facing systemic barriers to faring well under the formula. For instance, Kentucky State (the state’s historically black public university or “HBCU”) would be cut by an estimated 38%, Hazard Community and Technical College by 32% and Southeast Community and Technical College by 23% (both of which serve eastern Kentucky communities).17 A performance funding workgroup composed primarily of university presidents has been meeting to review the model and make recommendations to the General Assembly for some needed changes. Their recommendations focus primarily on the immediate budget situation and the need to keep all institutions at least at their 2021 funding levels in the 2022 budget with only additional funds on top of that floor being distributed through the performance formula.18

COVID-19 has driven an increase in need for health and other social services

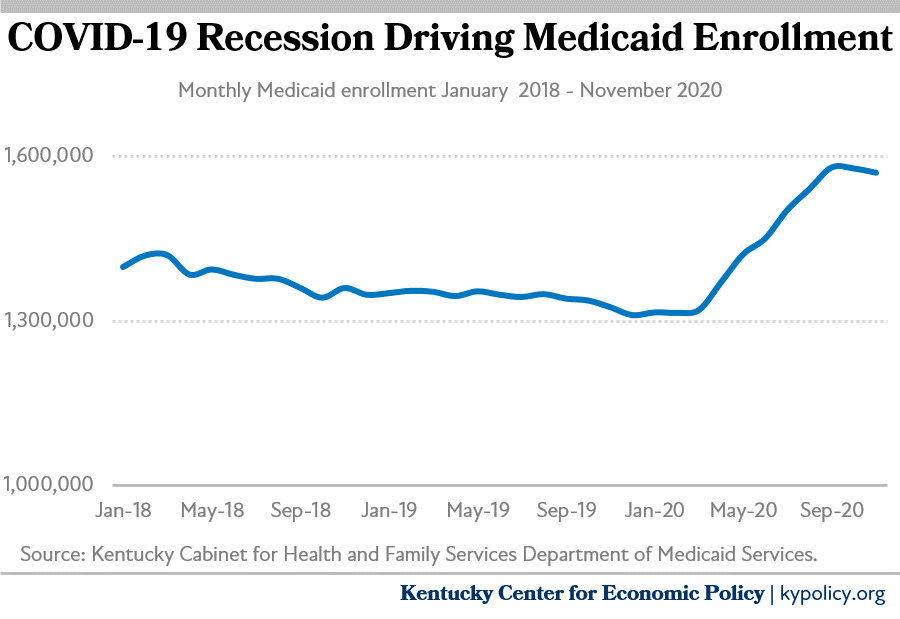

Many Kentuckians lost the health insurance they were receiving from their employer when they were laid off, and with many still jobless, the share of uninsured Kentuckians has spiked. Nationally, an estimated 14.6 million people lost health coverage due to layoffs between February and June 2020.19 Kentucky is no exception to this trend, contributing to a large increase in Medicaid enrollment of 255,645 (or a growth of 19.4%) between February and November. That growth was thanks in part to a new, temporary form of coverage known as presumptive eligible Medicaid for those uninsured and under 65 years old. Presumptive eligibility has been especially helpful for Black Kentuckians who have been disproportionately more likely to be laid off, more likely to become infected with COVID-19 and historically have been less likely to have health coverage.20

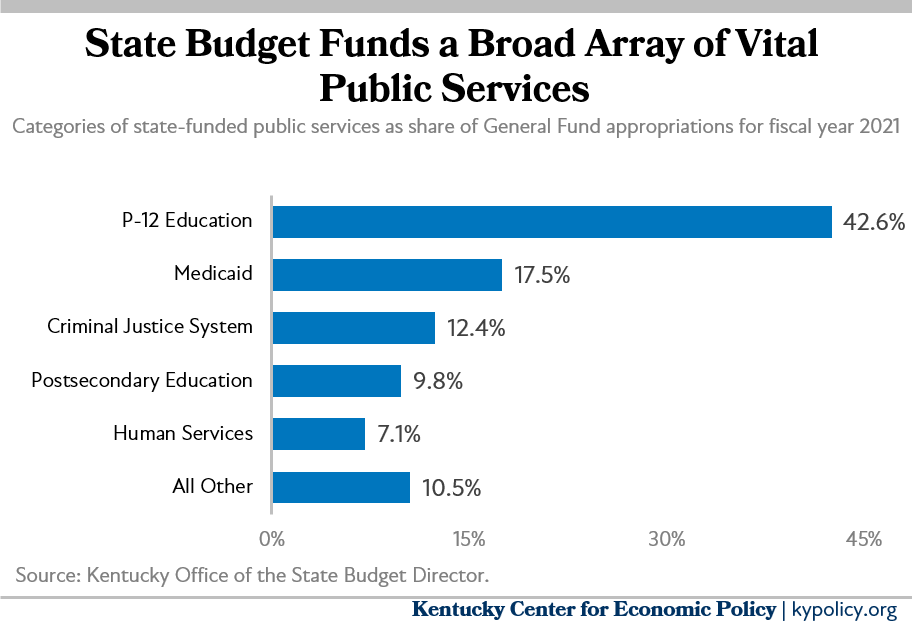

Medicaid is the second single-largest state General Fund expenditure with just under $2 billion in General Fund dollars during state fiscal year 2020, and $11.6 billion from all sources (the largest being federal funds). Federal action has helped to mitigate the added costs associated with the growth in Medicaid enrollment. Early in the pandemic, Congress enacted a 6.2 percentage point increase in its share of traditional Medicaid program costs, shifting the federal share up from 71.82% to 78.02% of costs. This increase was retroactive to the beginning of 2020 under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and expires only at the end of the quarter when the national public health emergency ends.21 According to state officials, this larger federal match rate has meant the state has had to cover $454 million less in Medicaid costs through mid-November 2020 than would otherwise be the case.22 If the national public health emergency declaration is not renewed in January when it is set to expire, Medicaid would be a larger driver of the budget than usual starting in April.

And while Kentucky has been paying a larger share of Medicaid expansion costs each fiscal year since 2017, the 2022 budget will be the first since then that will not contain an additional increase in the state’s share. Kentucky will now be paying 10% of the cost of Medicaid expansion without any further increase, while the federal government will pay 90%. In 2020, when Kentucky was paying roughly 9% of Medicaid expansion costs, the state paid a total of $281.3 million for expanded Medicaid.23 Medicaid expansion has been a lifeline to those who lost employer coverage during the pandemic and has helped to keep health care providers, including and especially rural hospitals, afloat during the downturn.24

Kentucky’s local public health departments (LPHDs) are also experiencing added strain as front-line responders to the pandemic. Heading into the COVID-19 pandemic, LPHDs had lost 34.2% of their workforce between 2012 and 2019 due to repeated rounds of budget cuts and added required pension contributions, resulting in a decrease to 2,269 public heath employees in 2019 spread across 60 health departments.25 Then in the 2020 General Assembly, House Bill 129 (supported by the Kentucky Health Departments Association) created a funding formula that ties state funding to the LPHD’s service area population — locking in staffing at close to 2019 levels.26 Although the governor provided $159 million in federal funds to the Department for Public Health to assist LPHDs, this money is temporary, and the LPHDs will be struggling to contain the virus, provide vaccinations and help local businesses comply with public health guidance well into the future. They will need further resources to be successful, especially in light of potentially devastating additional increases in their required pension contributions.27

Child care is another critical service that has been hit hard by the pandemic and resulting downturn. Like LPHDs, the child care industry has suffered over the past several years in part due to budget cuts, with the number of regulated child care providers falling from 4,460 in 2013 to 2,442 in 2019.28 According to the Cabinet for Health and Family Services, which regulates child care providers, this number fell again to 2,057 licensed centers and certified homes in late October (although there have also been a steady number of new provider applications in 2020 compared to 2019).29 Even before the pandemic, Kentucky did not have enough child care capacity, with half of Kentuckians living in a “child care desert” where there is not enough supply to meet the demand.30 The state received $65 million to help stabilize the child care industry through the CARES Act, but like other forms of federal aid, that money has been spent in 2020, and without further congressional action, the General Assembly will need to continue providing significant aid to help the industry weather the pandemic.31

Corrections budget includes savings from commutations but also increased costs due to COVID-19

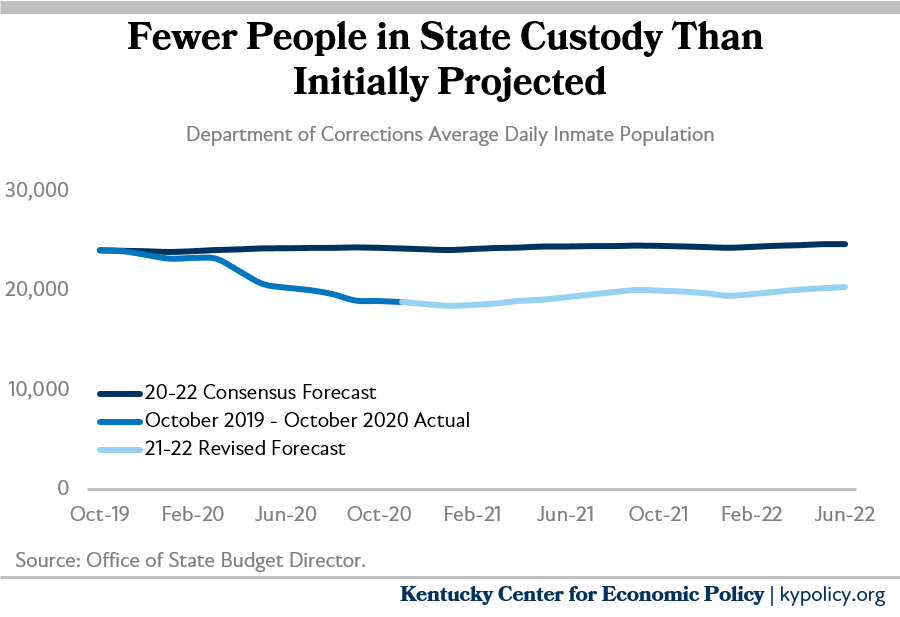

The costs of Kentucky’s criminal justice system have been going up in recent years along with the number of people the state incarcerates. A short-term counterforce to this trend, the Governor’s four rounds of commutations (three in April and one round in August), have meant that 1,881 fewer individuals are serving felony sentences in the state’s prisons and jails. That has led to lower costs, although as Secretary of Justice and Public Safety Mary Noble recently testified, there have been significant cost increases related to COVID-19 as well, such as for sanitation materials and practices and the provision of PPE (food prep, medical staff, etc.).32 Other recent factors leading to the decline (shown below) in the number of people serving felony sentences are recent increases in the parole rate and fewer people beginning felony sentences during this period.33 Secretary Noble indicated that it is not yet clear what these factors mean, on net, for the Cabinet’s 2022 budget request.

Meanwhile, some areas of the Justice Cabinet — such as the Department of Public Advocacy — continue to be underfunded in the 2021 continuation budget the General Assembly passed last year.34

Spiking pension payments still loom for quasi-governmental agencies

Because of House Bill 1 passed during the 2019 Special Session, 113 agencies with over 9,000 public employees like regional public universities, public health departments, domestic violence shelters and community mental health centers will be required to increase their contributions for their employees’ pensions from 49% to 85% of payroll or else buy their way out of the system altogether. No quasi-governmental agency chose to leave the system by the first deadline in spring 2020.35 In the 2020 General Assembly, the one-year continuation budget froze the contribution level at 49% and gave agencies another year to decide.36 In order to hold off potentially crippling increases in the pension contributions in the midst of a pandemic, the General Assembly will have to again freeze the contribution rate in the budget, provide additional funding for the quasis to make their increased pension costs, or otherwise provide relief to address the impossible choice set up by HB 1.

Federal aid has helped, but more is urgently needed

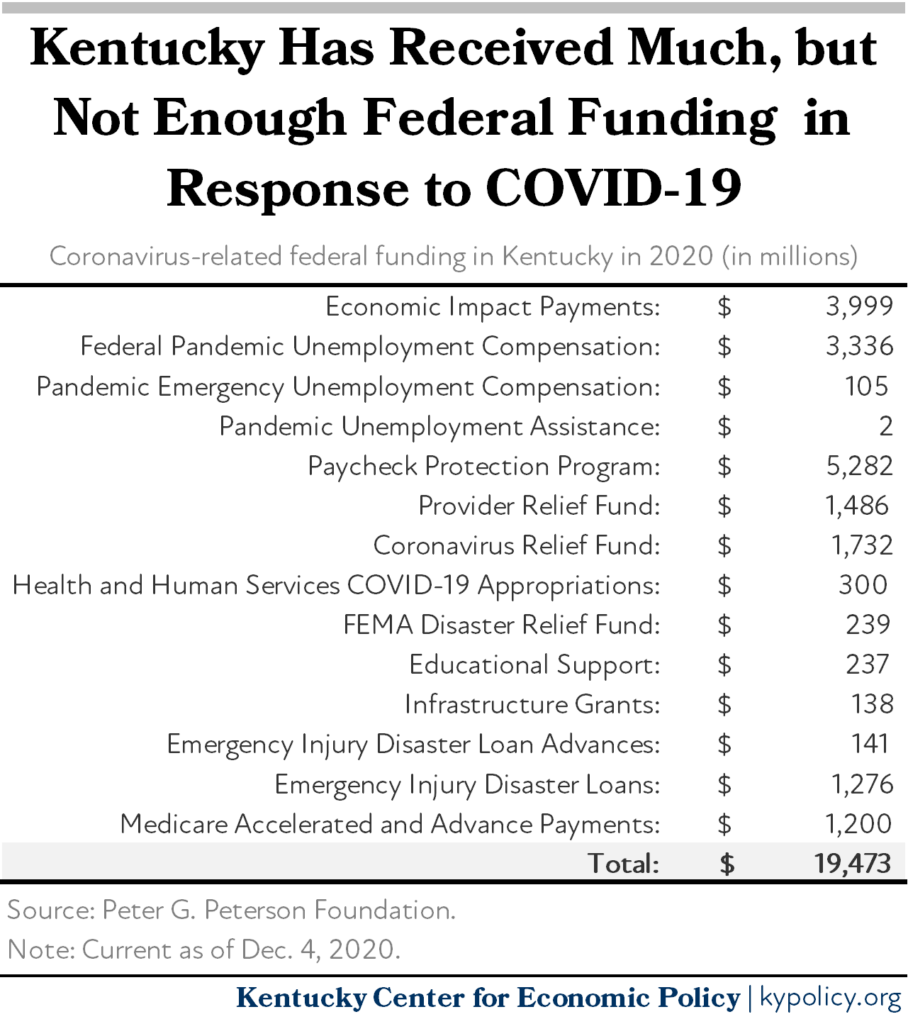

Through four rounds of federal legislation in March and April, Kentucky has received $19.5 billion in federal funds aimed at institutional and individual aid throughout 2020.37 This aid has been critical to stave off deeper hardship, shore up public revenues and keep the economy from freefall.

Combined, the Economic Impact Payments (stimulus checks), the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (or PUC, the extra $600/week in unemployment benefits from March to July), and the Paycheck Protection Program (or PPP, forgivable loans for businesses to meet payroll and halt layoffs) accounted for $12.6 billion — nearly 2/3 of Kentucky’s federal aid related to COVID-19. Kentucky’s state government received $1.6 billion in Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) monies, which, by and large, cannot be used to pay for normal government services. Whether to families, businesses or public agencies, much of this aid has expired, or will expire by year’s end. The one round of economic impact payments has largely been spent, PUC expired mid-July, the bulk of PPP has been deployed, and the CRF must be spent by the end of the year along with several other important sources of aid and economic security that expire in December 2020.38

State revenue insufficient to meet budget needs

In the new budget year, state tax revenue is expected to have very modest growth compared to the range of budget needs and without more federal aid. Understanding this inadequacy requires a look at both current impacts of the pandemic and long-term impacts of harmful tax policy choices.

Heading into the 2020 budget session, the Consensus Forecasting Group (CFG) projected that General Fund revenues would be the weakest since 1996, when the CFG was established, with anticipated growth of just 1.3% in 2021 and 1.8% in 2022. The weak projections were largely due to significant tax cuts passed by the General Assembly in 2018 and 2019 that primarily benefited banks, corporations and the wealthy.39 Given the projected lack of new revenues, compounding budget needs and the significant use of one-time revenue sources to balance previous budgets, the 2020 revenue outlook was already problematic even before COVID.40

Then COVID-19 hit during the middle of the 2020 session. In response, faced with a shortened legislative session and significant uncertainties about the economic impact of the pandemic on revenues and expenditures, the General Assembly elected to pass an austere one-year spending plan. The budget was based on a more pessimistic revenue forecast than the one provided by the CFG in December, reducing expected receipts by $128 million in Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 and $130 million in FY 2021.41

Kentucky ended FY 2020 with receipts that were $104.6 million better than those revised estimates, but that amount was still less than the very weak estimates from the CFG in December. 2020 receipts were bolstered by stronger-than-expected, year-over-year revenue growth of 3.9% during the first three (pre-pandemic) quarters of the year. However, receipts in the fourth quarter were significantly impacted by COVID-19, with an overall decline compared to the same period of the prior year of 4.5%. Absent the injection of over $19 billion in federal relief payments to businesses, individuals and the state discussed earlier in this report, the fourth quarter would have been significantly worse.42 The federal stimulus payments helped the state revenue picture including through increased spending subject to the sales tax, particularly through online retailers and big box stores, and increased withholding payments from unemployment benefits, which are subject to the state income tax.43

Kentucky ended FY 2020 with a General Fund surplus of $177.5 million, which included the additional revenues of $104.6 million, and reduced spending of $72 million helped by the use of federal aid monies to replace General Fund appropriations in some cases.44 Most of the surplus was deposited in the Budget Reserve Trust Fund (BRTF) or “rainy day fund” — which along with a scheduled contribution increased the balance by $163 million to $466 million. This brought the balance of the BRTF to 4% of FY 2020 General Fund revenue, the largest ratio in the state’s General Fund history. The purpose of the BRTF is to have resources on hand for unanticipated expenses and to provide funds if revenues are less than projected — a situation we will likely face in FY 2022.

Long-standing reliance on one-time monies will impact new budget

One way the General Assembly has addressed inadequacies in revenues in the past is through the use of “one-time” or non-recurring revenue sources to balance the budget, including fund transfers and lapses — often from accounts that receive revenues for a specific statutory purpose. In the 2021 budget, the General Assembly transferred or lapsed a total of $144 million from various agency-restricted funds or appropriations to the General Fund. Just to get back to the same inadequate starting point in the new 2022 budget, these revenues will need to be replaced.

General Fund revenue eroding as a share of Kentucky’s economy

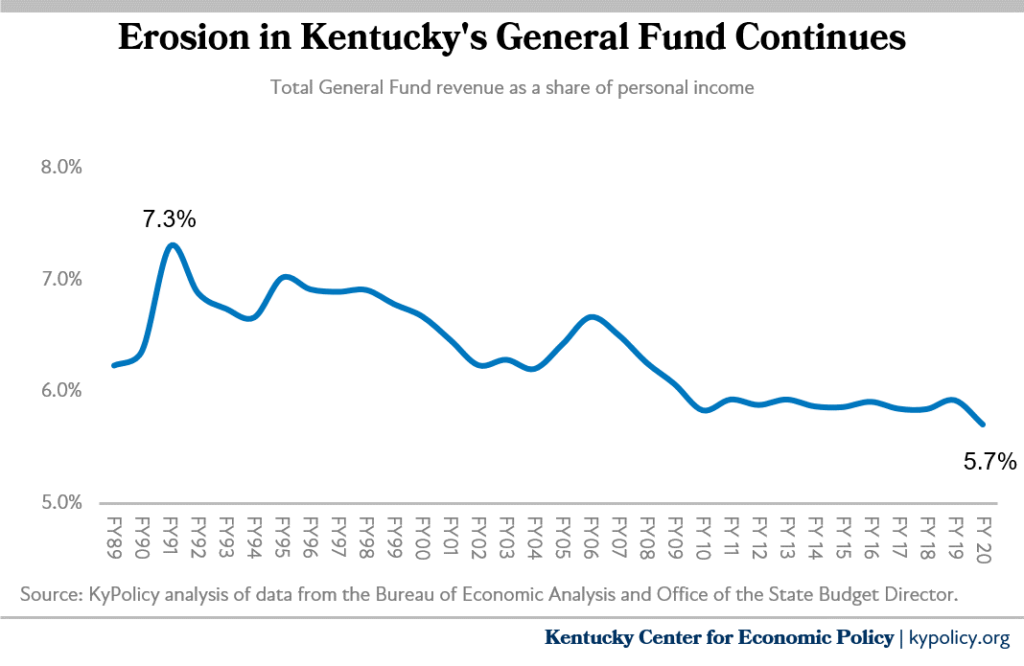

Revenue that is consistently inadequate to meet budget needs is the result of tax policy choices. Due to the legislature’s regular passage of new tax breaks as well as the growing impact of existing tax exemptions, revenue is actually eroding relative to the size of our economy. Kentucky’s General Fund as a share of total personal income has been shrinking and will continue to do so without policy changes that restore the connection between taxation and economic growth. Specifically, changes must address that the wealthiest Kentuckians, taking home the lion’s share of economic growth, currently pay the lowest total effective state and local tax rate, while Kentuckians of color and low- to moderate-income Kentuckians, for whom wages are largely stagnant, pay a larger share of their income in taxes.

The graph below shows that General Fund revenue has eroded from 7.3% of personal income in 1991 — after the Kentucky Education Reform Act raised revenue for the new school funding formula —down to 5.7% of personal income in 2020. That erosion amounts to $3.2 billion less in revenue than there would have been in 2020 had the General Fund simply maintained its size relative to the economy. Erosion is likely to continue after the 2018 and 2019 legislation reduced taxes even further for wealthy Kentuckians, banks and other special interest groups and shifted to reliance on slower-growing consumption and cigarette taxes.

This disconnect between Kentucky’s tax system and growth in the economy means that regardless of the level of economic growth, relative General Fund performance will likely continue to decline, resulting in revenues that chronically fall short of what is needed to support an adequate budget.

Consensus estimate adopted by the CFG assumes modest growth

The CFG met on Dec. 4, 2020, to recommend revenue estimates for the current and next fiscal year that will provide the starting point for the one-year budget the General Assembly must pass in the 2021 legislative session. Faced with continuing uncertainties about the trajectory of the pandemic and additional federal aid, the CFG adopted the control forecast, with a small upward revision of coal severance tax receipts.45 The control forecast assumes the phasing out of prior federal stimulus with no additional federal fiscal relief, and that even though there will likely be a vaccine in the middle of the fiscal year, there will be additional COVID-19 restrictions due to increasing infection rates throughout the winter.46

The CFG projects revenue growth of 1.4% in the current fiscal year, with receipts of $126 million more than assumed by the General Assembly in enacting the budget, for a total of $11.7 billion. Receipts have remained stronger than expected in the first part of this fiscal year due to the continued impact of federal fiscal relief. For FY 2022, the CFG estimate projects growth of 2.3%, with expected total revenues of $12 billion, $53 million more than the pre-pandemic estimate it provided for FY 2022 prior to the 2020 session.

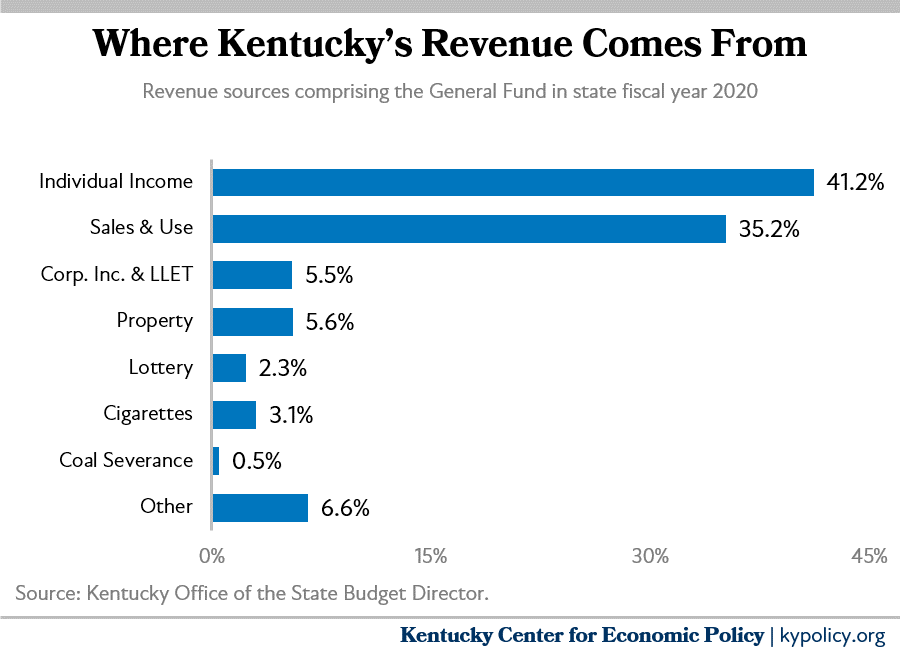

Individual Income tax

The individual income tax (IIT) has historically been Kentucky’s largest, best-growing and most progressive (based on ability to pay) single source of revenue, generating $4.8 billion in FY 2020 and accounting for 41% of the total General Fund. Because of the tax changes made in 2018 and 2019 that shift reliance away from the IIT to slower growing (sales) and declining (cigarette) consumption taxes, the share of revenues coming from the IIT has declined, further compromising the ability of revenues to keep pace with budgetary needs.

The CFG expects the IIT to grow $47 million over the enacted estimate of $4.8 billion for 2021, which is $53 million more than was collected in 2020. For FY 2022, the CFG predicts 4.5% growth in individual income tax receipts, with total receipts of $5 billion.

Sales tax

The sales and use tax is Kentucky’s second-largest source of revenue at 35%, generating $4 billion in FY 2020. Between 2019 and 2020, sales and use tax receipts grew by $133.3 million, experiencing strong growth over the first three quarters of FY 2020, followed by a decline of 5.9% in the fourth quarter.

The primary drivers of sales and use tax growth are significantly increased online sales and historically strong receipts from big box retail chains.

Sales tax revenues are expected to grow by 4% to $4.2 billion in 2021. The CFG estimates the sales tax revenues will grow by 2.7% to $4.3 billion in 2022.

Corporate taxes

Kentucky imposes two income-type taxes on corporations: the corporate income tax (CIT) and the limited liability entity tax (LLET). The taxes work together, with amounts paid under the LLET credited against the corporate income tax.47

Kentucky’s CIT and LLET generated $763 million in 2019, comprising 6% of the General Fund. In 2020, corporate income tax receipts fell by 16.2% to $639 million. The CFG projects revenues to fall by another 11.2% in 2021 followed by an increase in 2022 of 3.9%. Because the growth in 2022 is off of a significantly smaller base, projected revenues in 2022 are estimated to be $174 million less than in FY 2019. The relatively large increase projected for 2022 is due to banks moving from payment of the bank franchise tax to payment of the CIT, a move that is expected to result in an overall loss of revenues to the General Fund of $56 million beginning in 2022. The shift from the franchise tax to the CIT constitutes a tax reduction for banks.48

Road Fund revenues were significantly impacted by COVID-19 and remain weak going forward

The Road Fund, which is the primary source of state funds for road construction and maintenance, was hit hard by COVID-19, ending the 2020 fiscal year down 4.8% compared to the prior year, or $74 million short with all accounts experiencing reductions.49 The forecasts adopted by the CFG for 2021 and 2022 anticipate $86 million in new revenues for 2021 with total receipts of $1.57 billion (off of the significantly reduced base from 2020), and new revenues of $31.5 million for 2022.50

What needs to happen for a better budget

In order to continue providing crucial public services during this economic downturn, additional resources are needed.

Additional federal fiscal relief is needed

Unlike the federal government, Kentucky operates under a constitutional balanced budget requirement. That makes it harder for states to meet needs in recessions when revenue growth typically declines even while needs go up, and makes the federal government’s role in stimulus essential.

It is clear that the federal fiscal relief provided early in the pandemic has helped to sustain Kentuckians, the state’s economy and thus the General Fund so far. Research is clear that this kind of spending shortens and reduces the severity of recessions, putting the economy on a better long-term trajectory. With the announcement of several successful vaccine trials and the earliest phases of vaccine distribution launching in December and January, there is hope going forward. However, in the short term, the outlook is bleak without additional federal aid. There has been some recovery, but it has been slow, and there is evidence that it is slowing further.51

Many federal relief programs have ended, including the loss of $600 in supplemental unemployment benefits in July, and more recently, the end of $400 in additional benefits the Beshear administration chose to provide with federal matching funds. At the end of December, many other critical relief programs will also run out, including unemployment assistance for the self-employed, gig workers and independent contractors, and extended benefits beyond the 26 weeks states provide to unemployed workers. On December 31, federal rent and utility assistance, a moratorium on evictions and programs providing paid sick and family leave will all expire.52 In addition, funds provided to state and local governments to battle COVID will all be gone. Without these crucial supports, many Kentucky families will face unimaginable hardship, and our efforts to combat the virus and to repair our economy will be significantly compromised.

More state revenues are needed

As noted previously, Kentucky entered the 2020 budget session with significant revenue issues that have not been addressed, but have instead led to over decade of budget cuts and the use of one-time resources to balance the budget. Recently passed legislation has shifted reliance from the individual income tax, which requires more from those who have more, to consumption taxes, which require more from those who have the least. In addition, this shift harms the ability of our General Fund to grow with the economy.

The added fiscal strain created by the increased need for public expenditures to combat COVID, coupled with the economic fallout of the pandemic, make it more crucial than ever that action be taken to increase state revenues. In the long term, the state should return to a graduated income tax structure, as exists in 32 other states, and with a higher top rate than 5%, as exists in 26 other states.53 That will ensure the wealthiest Kentuckians — whose incomes have largely been protected during the pandemic — are pitching in adequately to prevent further cuts to education, health and other budget areas. While the short session presents the challenge of a supermajority vote requirement for revenue bills, tax policy changes that will create shared prosperity should be considered by the General Assembly in 2021 and in 2022.54 At the same time, the General Assembly must refrain from passing new tax breaks or shifts to consumption taxes that will damage the state’s ability to invest in communities.

Use rainy day fund as intended to provide relief and jump start the recovery

The purpose of the state rainy day fund is to provide additional resources during economic downturns to prevent harmful cuts that would make the state fall further behind. In crafting the 2021 budget, if federal aid is not adequate then monies in the BRTF should be used as intended — to provide the resources necessary to support continued investments in Kentucky and provide immediate relief for families and communities. While it is good policy to build up rainy day fund balances during good times, it is also good economic policy to spend these balances in hard times in order to help jump start the recovery. Especially if Congress fails to provide any or enough aid, Kentucky should do everything it can to provide relief to individuals and families struggling to get by through this crisis. Key needs include rental and utility assistance, food assistance through monies for food banks, emergency cash assistance and supplemental unemployment benefits.

- Jason Bailey, “Lessons from the Great Recession: Kentucky and Other States Need More Federal Relief,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy,” Apr. 29, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/lessons-from-the-great-recession-kentucky-and-other-states-need-more-federal-relief/.

- Dustin Pugel, “Tracking the Economic Fallout of COVID-19 in Kentucky,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Nov. 19, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/tracking-the-economic-fallout-of-covid-19-in-kentucky/.

- U.S. Department of Labor, “Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims Data,” accessed Nov. 17, 2020, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/claims.asp.

- U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, “Employment Table 1. Experienced and Expected Loss of Employment Income, by Selected Characteristics: Kentucky,” Week 19, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp19.html.

- Jason Bailey, “Kentucky’s Too-Slow Economic Recovery Faces New Threats,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Nov. 19, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/kentuckys-too-slow-economic-recovery-faces-new-threats/. The “real unemployment rate” refers to the combination of both those who have looked for work in the past four weeks at the time the survey was conducted (the official unemployment rate) in addition to the number of people who have lost work since February.

- Federal Open Market Committee, “Table 1. Economic Projections of Federal Reserve Board Members and Federal Reserve Bank Presidents, Under Their Individual Assumptions of Projected Appropriate Monetary Policy, September 2020,” Sept. 16, 2020, https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20200916.pdf.

- Jason Bailey, “Stimulus Payments Have Propped Up Weak Economy, and Harm Will Grow Without Additional Support,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jul. 14, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/stimulus-payments-have-propped-up-weak-economy-and-harm-will-grow-without-additional-support/.

- Pam Thomas, “Federal Relief Shored Up Kentucky’s Budget, but New Projections Raise Big Concerns About Remainder of Year,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Sept. 2, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/federal-relief-shored-up-kentuckys-budget-but-new-projections-raise-big-concerns-about-remainder-of-year/.

- This calculation is of total SEEK funds in the 2021 budget. State CARES Act funds were used in December 2020 in place of some of the state portion of SEEK.

- Ashley Spalding, “Cuts to K-12 Funding in Kentucky Among Worst in the Nation,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Mar. 6, 2019, https://kypolicy.org/cuts-to-k-12-funding-in-kentucky-among-worst-in-the-nation/.

- Ashley Spalding, “State Budget Cuts to Education Hurt Kentucky’s Classrooms and Kids,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 29, 2018, https://kypolicy.org/state-budget-cuts-education-hurt-kentuckys-classrooms-kids/.

- Anna Baumann, “Inequality Between Rich and Poor Kentucky School Districts Grows Again Even as Districts Face New COVID Costs and Looming Revenue Losses,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Sept. 2, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/new-analysis-inequality-between-rich-and-poor-kentucky-school-districts-grows-again-even-as-districts-face-new-covid-costs-and-looming-revenue-losses/.

- This calculation includes both the Education and Cabinet for Health and Family Services line items.

- Kentucky Department of Education, “CARES Act Allocations – 51520,” https://education.ky.gov/districts/fin/Pages/Federal-Grants.aspx. Kentucky Department of Education, Presentation to Budget Review Subcommittee on Education, Nov. 10, 2020.

- Dr. Aaron Thompson, Council on Postsecondary Education, Presentation to Budget Review Subcommittee on Postsecondary Education, Nov. 10, 2020.

- Council on Postsecondary Education, “RE: Distribution of 2020-21 Postsecondary Education Performance Fund,” Letter to State Budget Director, May 28, 2020, https://twitter.com/ASpaldingKY/status/1279888902468317189/photo/1.

- Postsecondary Education Working Group, Performance Funding Model Review, Nov. 4, 2020, http://www.cpe.ky.gov/aboutus/records/perf_funding/agenda-2020-11-04-pf.pdf.

- Postsecondary Education Working Group, Dec. 2, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AZVyqZOZ9cA&feature=youtu.be.

- Paul Fronstin and Steven Woodbury, “How Many Americans Have Lost Jobs with Employer Health Coverage During the Pandemic?” The Commonwealth Fund, Oct. 7, 2020, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/oct/how-many-lost-jobs-employer-coverage-pandemic.

- Dustin Pugel, “Black Kentucky Workers Are More Likely To Have Been Laid Off in the Pandemic, and Less Likely TO Have Been Hired Since,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Sept. 11, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/black-kentucky-workers-are-more-likely-to-have-been-laid-off-in-the-pandemic-and-less-likely-to-have-been-hired-since/. Kentucky Department of Public Health, “KY COIVD-19 Daily Summary,” accessed on Dec. 10, 2020, https://chfs.ky.gov/agencies/dph/covid19/COVID19DailyReport.pdf. Dustin Pugel, “Covering All Uninsured Black Kentuckians Is Crucial to Achieving Universal Coverage,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jun. 17, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/covering-all-uninsured-black-kentuckians-is-crucial-to-achieving-universal-coverage/.

- MaryBeth Musumeci, “Key Questions About the New Increase in Federal Medicaid Matching Funds for COVID-19,” Kaiser Family Foundation, May 4, 2020, https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/key-questions-about-the-new-increase-in-federal-medicaid-matching-funds-for-covid-19/#:~:text=Recent%20federal%20legislation%2C%20the%20Families,to%20the%20COVID-19%20pandemic.

- Eric Friedlander and Eric Lowery, Presentation to the Budget Review Subcommittee on Human Resources, Nov. 10, 2020, https://youtu.be/rWJ8VmPc8ZQ.

- Kentucky Department of Medicaid Services, “Medicaid Yearly Comparison,” received through an open records request on Dec. 9, 2020.

- Dustin Pugel, “Kentucky Has Much to Lose if Supreme Court Strikes Down the Affordable Care Act,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Oct. 14, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-has-much-to-lose-if-supreme-court-strikes-down-the-affordable-care-act/.

- KyPolicy analysis of Kentucky Retirement Systems Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports from 2012 to 2019, https://kyret.ky.gov/About/Board-of-Trustees/Pages/CAFR-and-SAFR.aspx.

- HB129 20RS, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/20rs/hb129.html.

- Jason Bailey, Pam Thomas and Dustin Pugel, “How Kentucky Should Spend Remaining Coronavirus Relief Fund Monies,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Sept. 28, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/how-kentucky-should-spend-remaining-coronavirus-relief-fund-monies/.

- Dustin Pugel, “Child Care Assistance Is a Great Investment for Kentucky, but Remains Inadequate,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 22, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/child-care-assistance-is-a-great-investment-for-kentucky-but-remains-inadequate/.

- Data provided to KyPolicy by CHFS by email on Nov. 10, 2020.

- Sheryl F Means, “Kentucky Child Care Deserts and Where to Find Them,” Prichard Committee, May 10, 2019, https://www.prichardcommittee.org/kentucky-child-care-deserts-and-where-to-find-them/.

- Jason Bailey, “What’s in the CARES Act for Kentucky?” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Apr. 3, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/whats-in-the-new-covid-19-relief-bill/.

- Robyn Bender, “Inmate Early Release Due to COVID-19,” Kentucky Justice and Public Safety Cabinet, Presentation to Interim Committee on Judiciary,” Dec. 3, 2020, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/8/12950/Dec%2003%202020%20Inmate%20Early%20Release%20Due%20to%20COVID-19%20Burikhanov%20KJPS%20PPT.pdf. Secretary Noble, Presentation to Budget Review Subcommittee on Justice and Judiciary, Nov. 10, 2020.

- Information provided by OSBD by email Dec. 4, 2020.

- Ashley Spalding, “Governor’s Proposed Additional Investment in Justice System Still Limited,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Feb. 26, 2018, https://kypolicy.org/governors-proposed-additional-investment-justice-system-still-limited/.

- John Cheves, “KY Lawmakers Urged Universities, Public Agencies to Leave Pension System. None Have.” Lexington Herald-Leader, Jan. 30, 2020, https://www.kentucky.com/news/politics-government/article239798938.html.

- Jason Bailey, “Legislature to Pass Austere 1-Year Budget with Major Uncertainty as to Revenues,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Apr. 1, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/legislature-to-pass-1-year-austere-budget-with-major-uncertainty-as-to-revenues/.

- Peter G. Peterson Foundation, “How Much Coronavirus Funding Has Gone to Your State?” Oct. 29, 2020, accessed Nov. 23, 2020, https://www.pgpf.org/understanding-the-coronavirus-crisis/coronavirus-funding-state-by-state.

- Jessica Klein, “With Many Forms of Assistance Ending in December, Kentuckians Need Federal Relief Before the New Year,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Nov. 16, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/with-many-forms-of-assistance-ending-december-31-kentuckians-need-federal-relief-before-new-year/.

- Jason Bailey, “Tax Cuts Causing the Worst Revenue Projections Since Consensus Forecasting Began,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 23, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/tax-cuts-causing-the-worst-revenue-projections-since-consensus-forecasting-began/.

- “What Does Kentucky Value? A Preview of the 2020-2022 Budget of the Commonwealth,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, January 2020, https://kypolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Final-online-draft.pdf.

- Bailey, “Legislature to Pass Austere 1-Year Budget with Major Uncertainty as to Revenues.”

- Office of State Budget Director, “Financial Outlook Report,” John Hicks, Janice Tomes, Kevin Cardwell, Greg Harkenrider, J. Michael Jones, presented to the Interim Joint Committee on Appropriations and Revenue, Aug. 19, 2020, https://osbd.ky.gov/Publications/Documents/Presentations/OSBD%20Presentation%20to%20AR%20Comm-8.19.2020.pdf.

- Thomas, “Federal Relief Shored Up Kentucky’s Budget, but New Projections Raise Big Concerns About Remainder of Year.”

- Thomas, “Federal Relief Shored Up Kentucky’s Budget, but New Projections Raise Big Concerns About Remainder of Year.”

- Office of State Budget Director, Consensus Forecasting Group Revised Revenue Estimates, Dec. 7, 2020, https://osbd.ky.gov/Publications/Documents/Official%20Revenue%20Estimates/Revised%20FY21-FY22%20Offical%20CFG%20Estimates.pdf.

- J. Michael Jones, Office of State Budget Director, Presentation to the Consensus Forecasting Group, Dec. 4, 2020, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/209/12954/CFG%20Economy%20slides%2012042020.pdf. The CFG is presented with three sets of estimates each time it meets including a control (most likely) estimate, as well as optimistic and pessimistic scenarios based on differing assumptions about the economy.

- Because these taxes are interrelated, the Consensus Forecasting Group (CFG) started forecasting them together beginning with the Aug. 2017 planning estimates.

- Pam Thomas, “Bank Tax Break Passed This Session Was Not What Proponents Claimed,” Mar. 27, 2019, https://kypolicy.org/bank-tax-break-passed-this-session-was-not-what-proponents-claimed/.

- Office of State Budget Director, Governor’s Office of Economic Analysis, “Commonwealth of Kentucky, Quarterly Economic & Revenue Report, Fourth Quarter Fiscal Year 2020, Annual Edition,” Aug. 27, 2020, https://osbd.ky.gov/Publications/Quarterly%20Economic%20and%20Revenue%20Reports%20%20Fiscal%2016/20-4thQrtRevenue.pdf.

- Office of State Budget Director, Consensus Forecasting Group Revised Revenue Estimates.

- Bailey, “Kentucky’s Too-Slow Economic Recovery Faces New Threats.”

- Klein, “With Many Forms of Assistance Ending in December, Kentuckians Need Federal Relief Before the New Year.”

- Federation of Tax Administrators, “State Individual Income Tax Rates,” https://www.taxadmin.org/assets/docs/Research/Rates/ind_inc.pdf.

- Jason Bailey and Pam Thomas, “Revenue Options that Strengthen the Commonwealth,” March 2020, https://kypolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Revenue-Options-April-2020-web.pdf.