Introduction

The General Assembly faces a critically important opportunity with the 2024-2026 Budget of the Commonwealth. A strong national economy has resulted in robust recent state revenue growth, but the legislature is putting an excessive amount of money away in its Budget Reserve Trust Fund (BRTF) that can be better used to reinvest in education, health, social services and other critical needs after more than a decade of state budget cuts. These monies give Kentucky the chance to begin charting a better course.

The Budget of the Commonwealth reflects Kentucky’s values and priorities. Adequately, equitably funded schools would mean all Kentucky children, regardless of their zip code, could receive a high-quality education. Well-resourced supports for the elderly, children and people with disabilities would help families thrive. Less spending on incarceration, and more on mental health, infrastructure and college affordability, could enhance well-being. These kinds of policy choices remove barriers to opportunity and security that people face because of race, gender, wealth and the part of the state where they live. They also can create a state where people want to live, raise a family, work and do business.

Unfortunately, Kentucky falls short because of budget austerity that has limited investment in the essential public goods and services needed to support thriving communities. Long-term growth in tax expenditures, which take money off the top for various tax credits, deductions, carve-outs and other breaks, has historically limited the resources available for the budget. And more recently, a focus on reducing the individual income tax – and building up reserves to protect against the inevitable budget shortfalls if that effort is successful — has meant meager budgets despite more available resources.

This report describes in detail the funding opportunity and the imperative to reinvest in Kentucky. It describes the condition of the budget across different areas of government over time, and how everyday Kentuckians are affected by these policy choices – including important areas where expiring federal COVID relief funds provided support in the previous biennium. The report further warns against continuing to overfund the state’s BRTF in order to finance additional income tax cuts, which benefit the wealthy at the expense of investments Kentucky needs to thrive.

Part 1: Revenue

Kentucky has a historic opportunity to invest

For the first time in many years, the General Assembly will enter a budget session with billions of dollars that can be used to craft a budget that better invests in community needs and delivers for the people of Kentucky. This money is there due to economic stimulus provided by federal policies including pandemic aid, but the legislature has largely stockpiled the resulting billions in the BRTF. Lawmakers face a historic choice this legislative session. Do they finally reinvest in pressing community needs and prevent funding cliffs created by the end of federal pandemic aid? Or do they continue putting excessive money in reserves in order to fund future additional income tax cuts and the immense revenue loss those cuts will cause?

The benefits of federal policy continue to result in strong revenues

The past three years have seen unusually strong revenue growth because of the economic stimulus provided by federal COVID relief, which has driven the unemployment rate to historic lows. In addition, tax receipts rose as shifts in buying patterns and global shutdowns during COVID (in addition to the war in Ukraine) resulted in temporarily high inflation, and as corporate profits reached record highs. Kentucky is not alone in this situation, with a majority of states seeing revenues exceed expectations in recent years.1

Moving into the next budget cycle, these conditions are changing. The economy is currently expected to remain strong, buoyed in part by subsequent federal investments in infrastructure, clean energy and onshore manufacturing. But COVID funds must be expended by Dec. 31, 2026, and higher interest rates could still dampen economic growth.2 In addition, Kentucky’s revenues will be further reduced by new rounds of tax cuts enacted by the General Assembly during the 2022 and 2023 legislative sessions.3

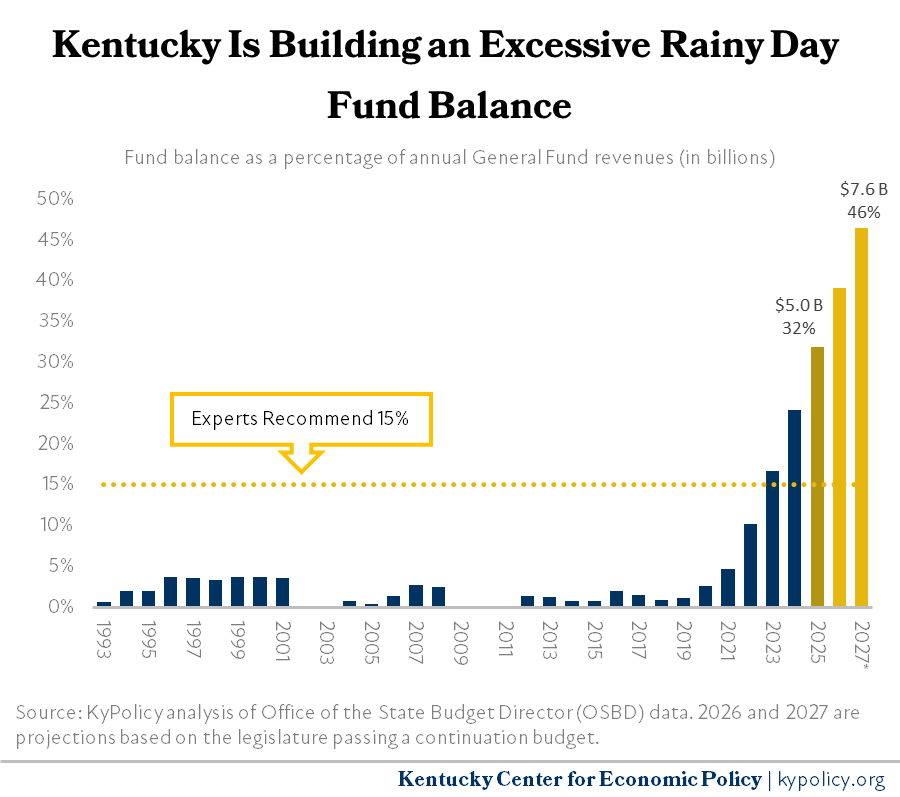

House Bill (HB) 8, passed in 2022, allows for cuts to the individual income tax rate in 0.5% increments if certain conditions are met.4 The formula, which relies on a one-time snapshot of the state’s fiscal picture to make permanent tax cuts, includes a two-part trigger. The first is that the BRTF balance must be greater than 10% of General Fund receipts during the fiscal year. The second is that revenues must exceed spending by at least the cost of a 1% cut in the income tax (which at current levels is around $1.2 billion). Efforts to reach the second trigger in this formula require that spending remain far below revenues each year, building an excessive balance in the BRTF far beyond what is necessary to address future emergencies. Amounts stockpiled in the BRTF include significant recurring revenues that provide an opportunity for the General Assembly to invest more in ongoing critical budget needs without compromising the safeguards needed for emergencies.

Revenue growth slowed in fiscal year 2023 due primarily to income tax cuts

After moving to a 5% flat income tax in 2018, the General Assembly lowered the income tax rate to 4.5% in January 2023 and then followed its newly enacted formula to implement another cut to 4% that will start in January 2024. As these cuts are implemented, General Fund revenue growth slowed significantly in FY (fiscal year) 2023 to just 3% following two years of double-digit increases. Within the General Fund, tax receipts actually fell by 5.4% in the fourth quarter of FY 2023, indicating that General Fund receipts were propped up by non-tax receipts, including interest on investments from the large BRTF balance and lottery dividend payments.5

Despite the slower growth, receipts remained up because of record low unemployment and inflation that, though decreased from 2022, has still been comparatively high. The state ended FY 2023 with a surplus of $1.4 billion, because the General Assembly did not appropriate additional revenues during the 2023 legislative session despite a revised forecast showing higher receipts were expected. Some notes on the major receipt categories for FY 2023:6

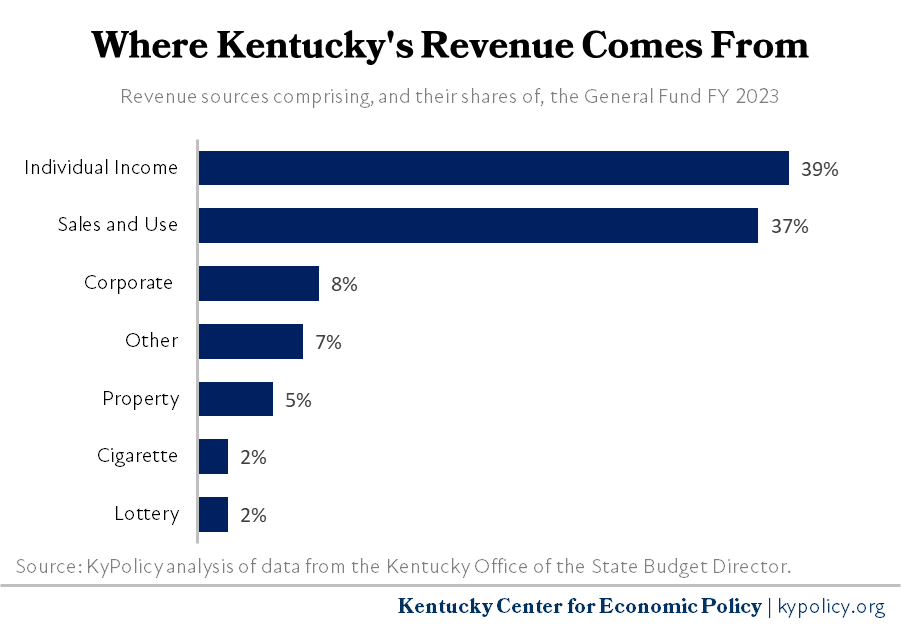

- As a result of the rate cut from 5% to 4.5% beginning Jan. 1, 2023, individual income tax receipts were down 3.4% compared to 2022. Despite this reduction, the individual income tax was responsible for the largest portion of the surplus at 36% due to strong underlying income growth.

- Sales and use tax receipts increased 10.1% year over year — a double-digit increase for the third year in a row. This increase was due to inflation, which drives up prices and, consequently, sales taxes, along with higher wages and a low unemployment rate resulting in more purchasing by consumers. Sales tax receipts were responsible for 21% of the surplus.

- Combined corporate income and Limited Liability Entity Tax taxes grew by 3%, or $35 million, year over year. This modest growth follows two years of extraordinary increases of 38.1% in FY 2021 and 34.4% in FY 2022, due in large part to record corporate profits that have continued since the pandemic. Revenues from these two taxes have increased from $939.2 million in FY 2020 to $1.2 billion in FY 2023. Business taxes were responsible for 22% of the surplus.

- Property taxes had an unusual year in FY 2023, increasing by 7%. The increases were primarily due to a 9.7% increase in collections from tangible personal property and a 10.2% increase in collections on motor vehicles due to inflation in vehicle values. Property taxes accounted for 7% of surplus revenues.

- Of particular note in FY 2023 is the strong growth in the “Other” category, which consists of 59 smaller accounts including less significant taxes, fees and other receipts. Within this category, income from investments was $150 million more than in FY 2022 due to the substantial balance of the BRTF. Receipts in this account also included a one-time legal settlement of $225 million from Poker Stars, and $15.9 million from five months of collection of the new ride sharing tax.7

As illustrated by the graph on the next page, despite the rate reductions, the individual income tax remains the strongest revenue source for the General Fund. But the gap between revenues from the individual income tax and sales tax is shrinking, with the individual income tax falling from 41% of General Fund revenues to 39% since the tax rate reductions began. As additional cuts are implemented, revenue from the individual income tax is projected to fall behind sales tax revenue in the next biennium. Reducing the most productive revenue source, and doing nothing to replace it, will inevitably squeeze the resources needed to support schools, health care, infrastructure and other public investments.

Forecast shows modest revenue growth that doesn’t keep up with inflation after the impact of tax cuts are considered

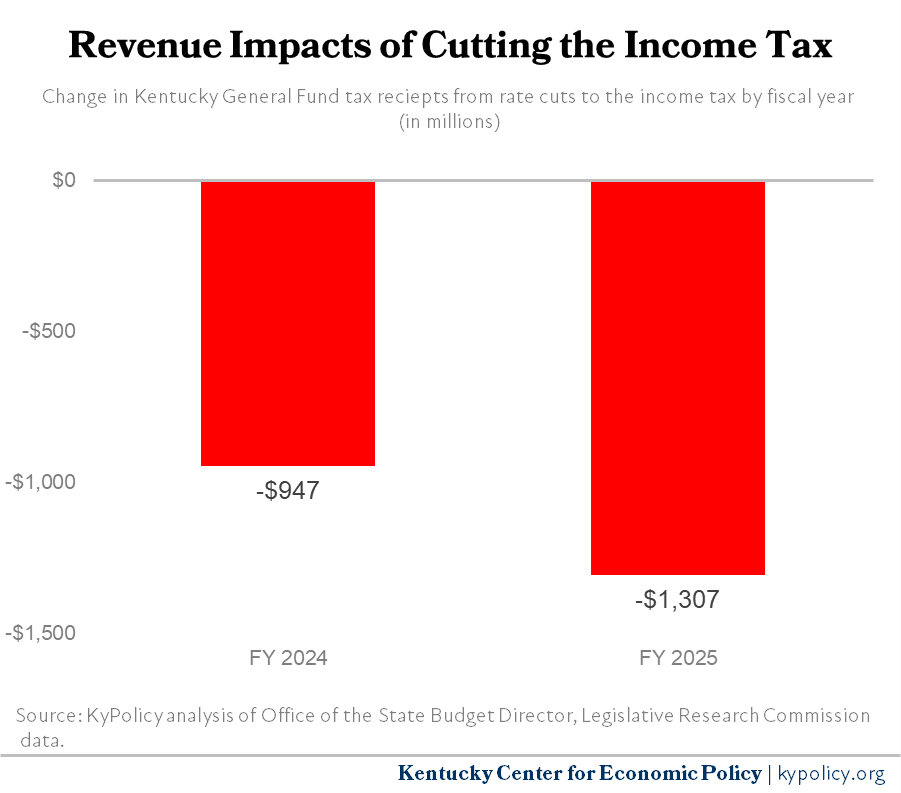

Although tax returns reflecting the cut from 5% to 4.5% will not be filed until April of 2024, the cuts show up before then in reduced “withholding” revenues, which is the income tax collected from individuals’ paychecks, and in reduced declaration payments, which are quarterly payments made by individuals on other types of income. In the first six months of FY 2023, withholding tax revenues grew by an impressive 7.7% compared to the prior year. However, after the cut went into effect, withholding revenues declined by 3.9%, or approximately $172 million. Declaration payments were down 19.9% overall.8 As illustrated in the graph below, as the 2023 cuts fully phase in and the 2024 cuts begin, General Fund revenues will be reduced by over $1.3 billion in the first year of the next biennium.

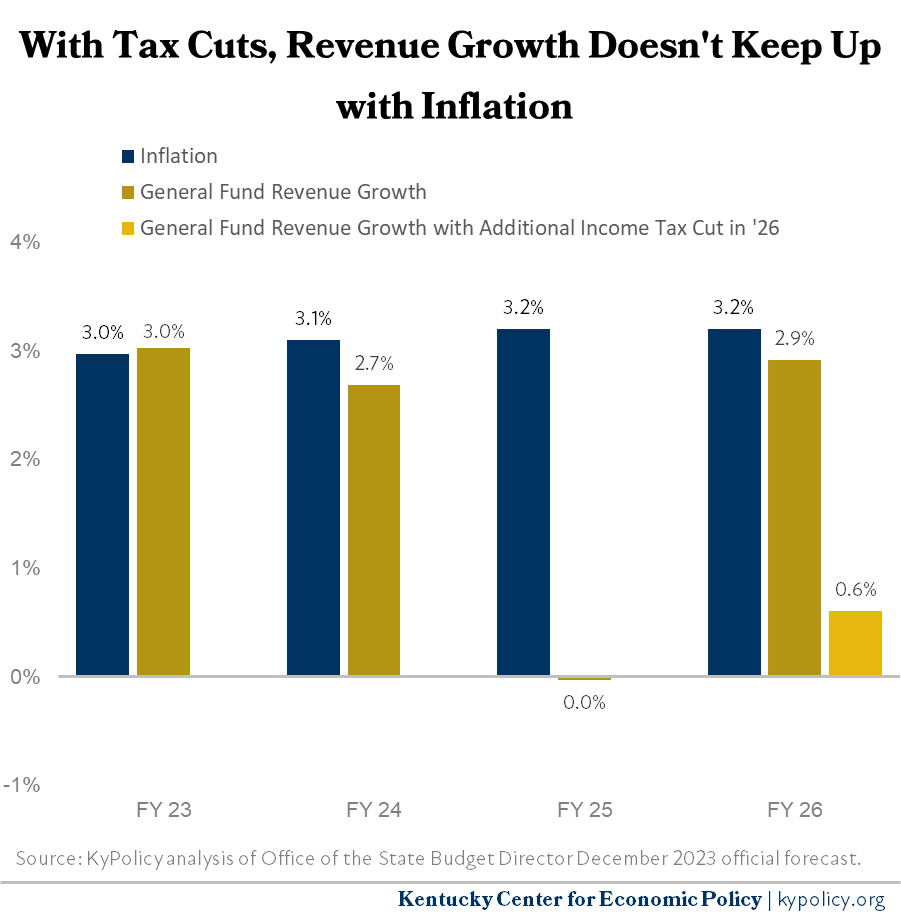

Moving forward, taking these and other tax cuts enacted by the General Assembly into account, revenues are projected to grow 2.7% this year, not at all in 2025 and 2.9% in 2026. These estimated growth rates do not keep up with projected inflation of 3.1% to 3.2% annually over the next few years, as shown in the graph below.9 FY 2026 comes closest, but that will change if an additional half-point cut in the income tax rate is triggered next year and approved by the 2025 General Assembly (taking effect in January 2026).

Income tax cuts provide huge benefit to the wealthiest and nothing for those most in need

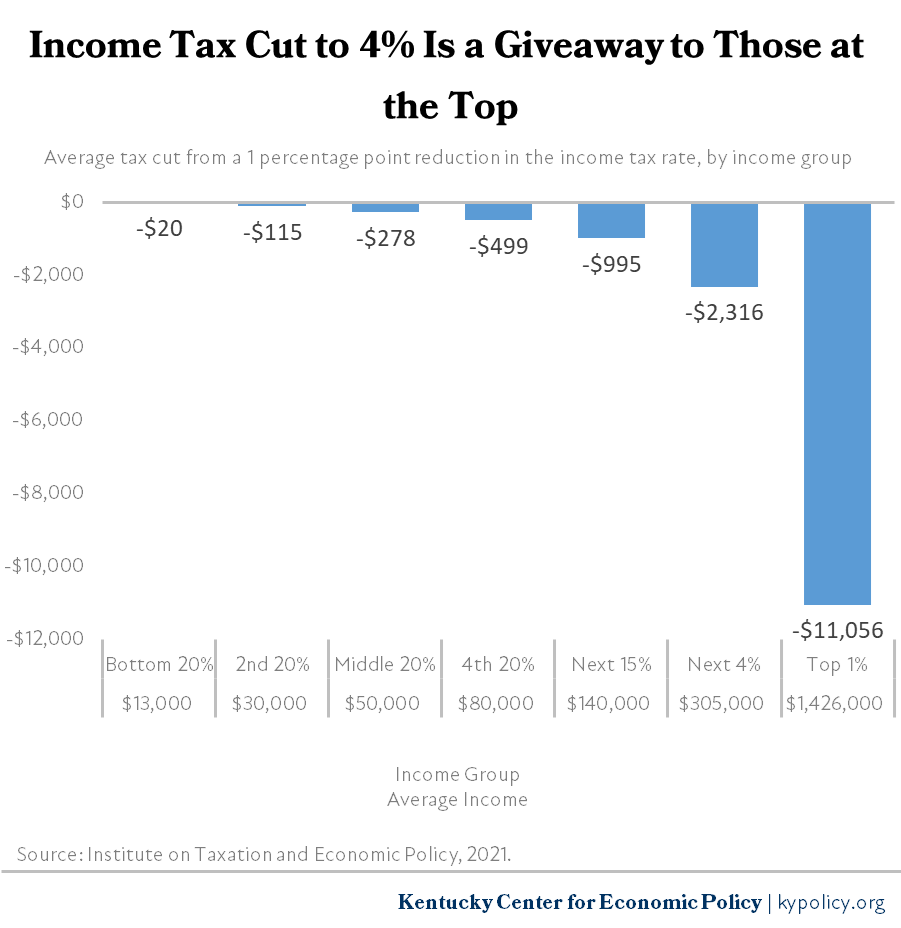

A close look at who benefits most from the income tax cuts already enacted reveals that the richest 1% of Kentuckians, who make $1.4 million a year on average, will receive $11,056 annually on average from the reduction of the income tax rate from 5% to 4%. In contrast, the middle 20% of Kentuckians will receive $278 on average, or $5.35 a week.

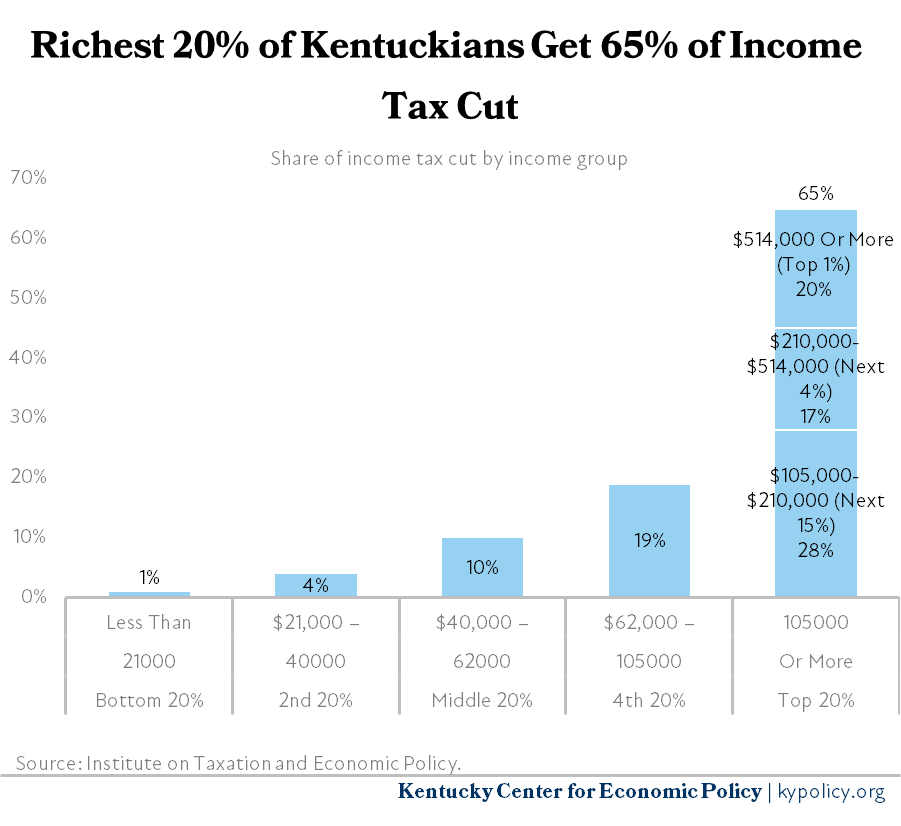

The total dollars in benefit will also flow overwhelmingly to the people at the top because of Kentucky’s substantial and growing income inequality. The 20% of people with the highest incomes will get 65% of the tax cuts, as shown below. The richest 1% of Kentuckians alone will get 20% of the cuts, while the poorest 20% will get only 1%.

Because Kentucky has a “family size tax credit” that entirely exempts people below the poverty line based on family size from the income tax, the tax cuts will be of no help to Kentuckians most in need of aid.10 The credit also phases out between 100% and 133% of poverty, meaning those individuals already have their income tax liability reduced between 10% and 90% before the tax cut. Thus, a family of four with modified gross income below $30,000 pays no income tax already and will not benefit from the income tax rate reductions, while a family of four with a modified gross income between $30,000 and $39,000 already has their income tax reduced by the family size credit.11

Most of the state’s 768,000 seniors also do not benefit from these tax cuts. The state already exempts Social Security income from the income tax and exempts the first $31,110 of other retirement income from the tax. The median non-Social Security retirement income in Kentucky is only $12,000, and of the 548,000 retirees who receive retirement income other than Social Security, 79% receive less than $31,110.12 We therefore estimate that approximately 85% of all retirees will receive no benefit from the tax cuts.

These tax cuts also worsen racial inequities. A total of 92% of Kentuckians in the top 20% of tax filers are white, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, while 86% of total tax filers are white. In contrast, only 4% of Black Kentuckians are in the top 20% of filers, despite being 8% of all filers. The Black poverty rate is 24.4% compared to the white poverty rate of 15%, meaning nearly a quarter of Black Kentuckians most in need of the help will receive nothing from the tax cuts already enacted.13

General Assembly is holding down the budget and excessively building up the rainy day fund

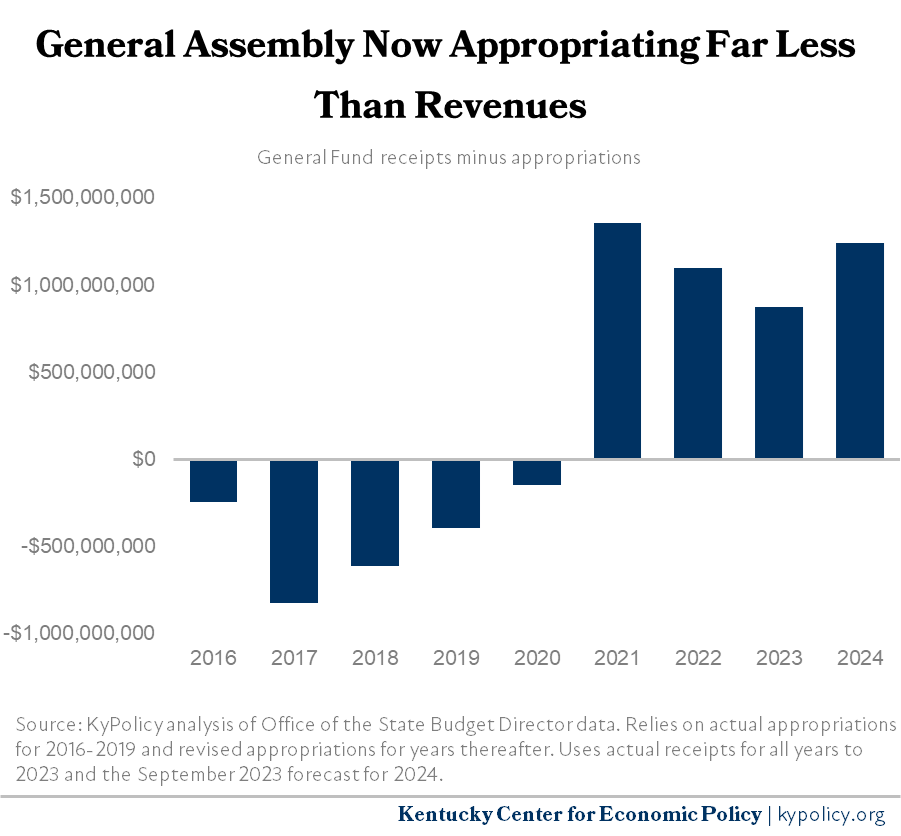

To try to meet the triggers to further cut taxes, lawmakers have suppressed spending relative to revenues since 2021, which has resulted in an excessively large balance in the BRTF. As shown in the graph below, budgeted appropriations regularly exceeded revenues in years prior to 2021, with the legislature using fund transfers — which are resources moved from other accounts in state government to the General Fund — to fill the resulting gap. The picture dramatically reversed starting in 2021, with the state now receiving approximately $1 billion more each year in General Fund receipts than it spends through General Fund appropriations. Like nearly all states, revenues rose due to the positive economic effects of federal pandemic stimulus and temporarily higher inflation, but Kentucky largely has not used those added resources to meet budget needs.14

Instead, the legislature is using these revenues to justify tax cuts and build up the BRTF. Currently, the BRTF balance exceeds $3.7 billion, or 24% of the state’s expected revenues this year.15 With revenues projected to exceed appropriations by $1.2 billion again this year, the balance may grow to $5 billion, or 32% of revenues, by next year. That amount far exceeds a careful savings level of 10% to 15% of revenues most experts say is needed to protect against a future recession.16 For comparison, the National Association of State Budget Officers last spring estimated the median rainy day fund balance for states in FY 2023 to be 12% of General Fund expenditures, putting Kentucky’s balance as the sixth highest as a percentage of General Fund expenditures among all states.17

Because the formula to further reduce taxes requires expenditures to be over a billion dollars below revenues, continued efforts by the General Assembly to reduce appropriations will result in ongoing budget surpluses, further increasing the already excessive balance in the BRTF at the expense of all other public service needs. As illustrated in the graph above, at the current pace and if the General Assembly continues to focus on meeting the triggers for income tax cuts in the next two-year budget, the BRTF balance could reach nearly 50% by the end of the budget biennium.

The challenge of cutting the budget enough to meet the formula was made clear this fall. Despite an effort to hold down appropriations, the condition requiring suppressed spending was not met in only the second year the formula was in effect.18 Thus, an additional half-point cut will not occur in January of 2025. The considerable costs of disaster relief from the eastern Kentucky floods, among other pressing needs, made hitting the trigger this year impossible.

Part 2: Investments

Reinvestment through the budget is imperative

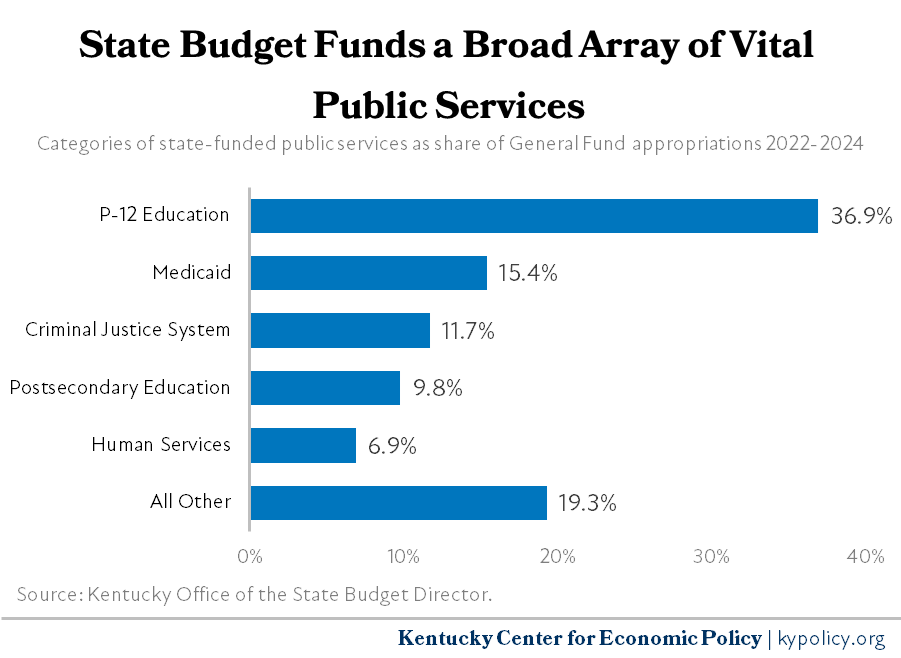

While the previous section of this report looked at the revenue context for what is possible in the 2024 General Assembly, this section will explore the need to restore critical areas of the budget and address immediate concerns associated with the end of pandemic funds and with natural disasters that have hit the state. In addition to providing an overview of state spending, including federal relief funds, the following analysis gives examples of the compounding impact of a decade or more of cuts. As context, the chart below illustrates the major ways the state’s General Fund, which totals over $14 billion in 2024, is spent.

Education

State funding for P-12 education

P-12 education remains the largest area of General Fund investment in the state budget, although in recent years it has declined as a state priority. In the eight budgets between 2006 and 2021, P-12 education received between 43% and 45% of total General Fund appropriations. In the current biennial budget, it received just 37%.19 The state faces growing inadequacies and inequities in public school funding, even while research shows increased school spending improves student outcomes and spending cuts correlate with lower college-going rates, lower test scores and larger test score gaps by income and race.20

SEEK funding has declined in real dollars

The largest component of education funding is the Support Education Excellence in Kentucky (SEEK) formula, which provides state funding to school districts based on wealth and local effort. SEEK includes what is called a “base guarantee” of funding for every student. The amount of this guarantee is established in the budget. The SEEK formula also includes additional funds (referred to as “add-ons”) for students eligible for free lunches, students with disabilities, students with “limited English proficiency,” and home and hospital services, in addition to transportation, which will be discussed in more detail later in this section.

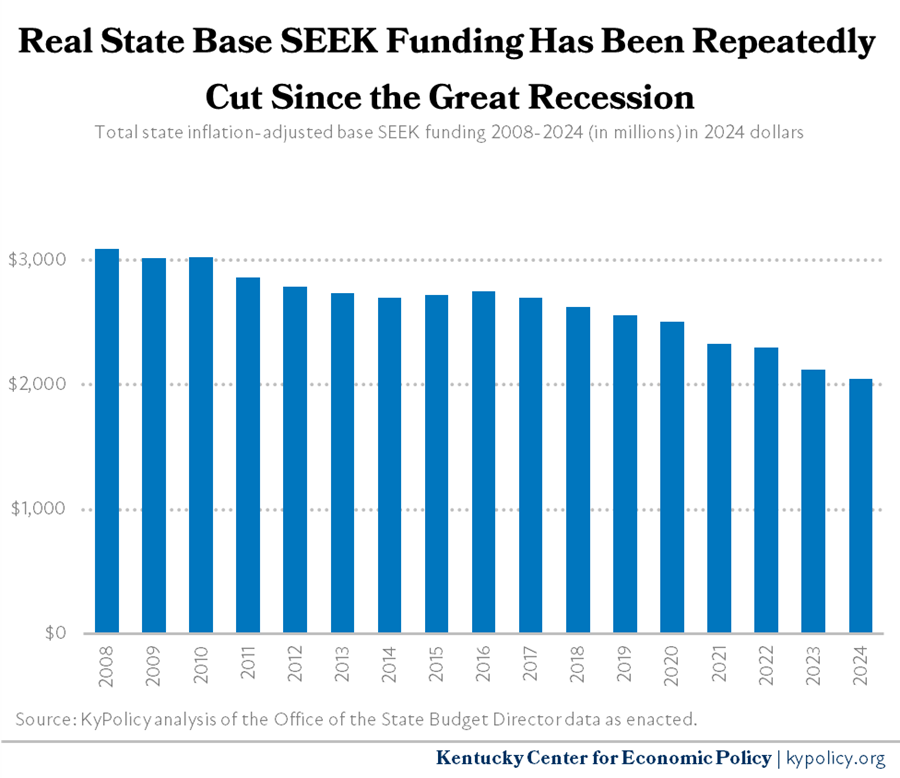

For 2024, the state appropriated $2.044 billion dollars for total base SEEK, compared to $2.097 billion in 2008, prior to the Great Recession.21 As reflected in the graph on the next page, in inflation adjusted terms, this is a 34% decline in base SEEK funding from 2008, and significantly lower than 2022 as well.

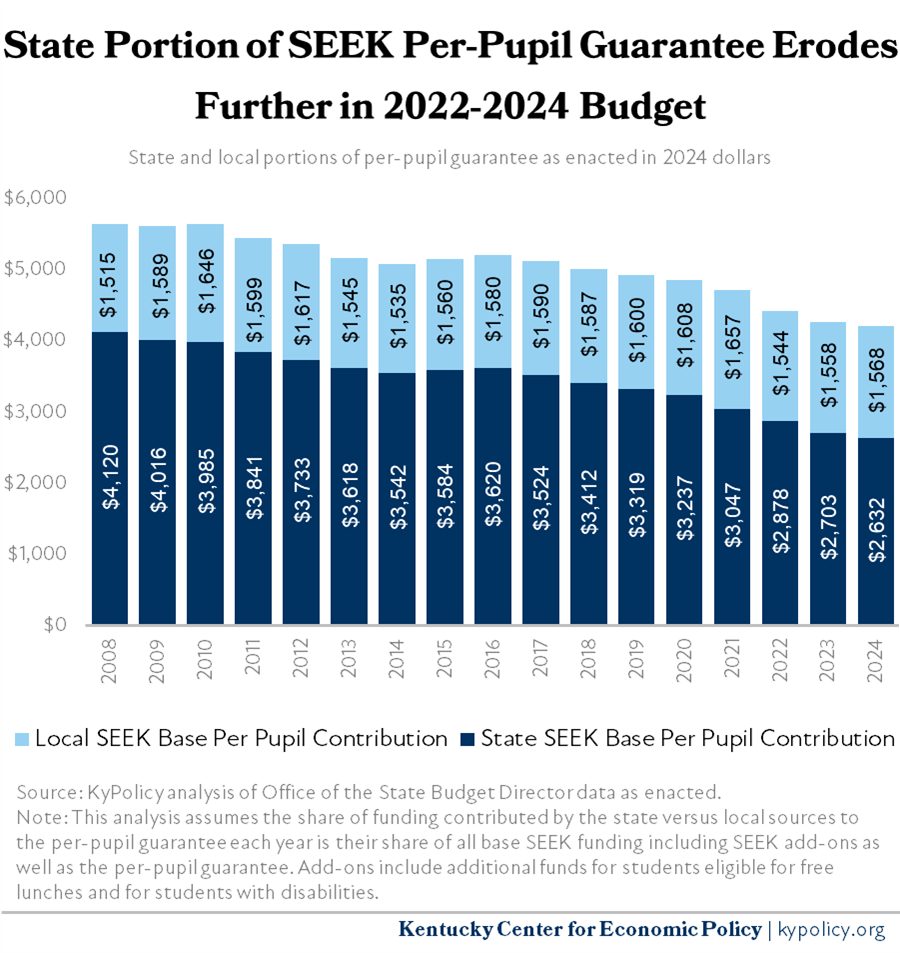

The base per-pupil guarantee amount, which is funded through a combination of state and local funding, with the state contributing more to districts that have less property wealth to equalize the lack of local capacity, increased from $4,000 in FY 2022 to $4,100 in FY 2023 and $4,200 in FY 2024.[i] These increases resulted in the state portion of base funding actually declining in inflation-adjusted terms, as illustrated below.[ii]

The state portion declined on a per-pupil basis by $162 between 2008 and 2024, while the local portion grew by $540. Thus, the cost of the nominal increase in base funding is being borne primarily by local school districts. When inflation is factored in, as shown in the graph below, the combined state and local per-pupil guarantee is lower in 2024 than it was in 2008 by $1,435 per student, a decline of 25.5%.

[i] Ashley Spalding, Dustin Pugel and Jason Bailey, “Budget Agreement Includes Only Modest Increase in Most Areas of Budget, Salary Increases for State Workers,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, March 29, 2022, https://kypolicy.org/budget-agreement-includes-only-modest-increases-in-most-areas-of-budget-salary-increases-for-state-workers/.

[ii] As noted in the official enacted budget published by the Office of State Budget Director, “For the last ten years, the base per pupil amount for Kentucky’s formula funding program for elementary and secondary schools has only grown 2.5 percent and has been static for the last four. In the last four years, the SEEK program’s base per-pupil has been $4,000. The budget raises that to $4,100 in fiscal year 2023 and to $4,200 in fiscal year 2024. Despite the increase in the base per pupil amount, a decline in estimated school headcount and an increase in local property valuation, result in the base SEEK allocation decreasing from the enacted fiscal year 2022 amount. Office of State Budget Director, “2022-24 Budget of the Commonwealth.”

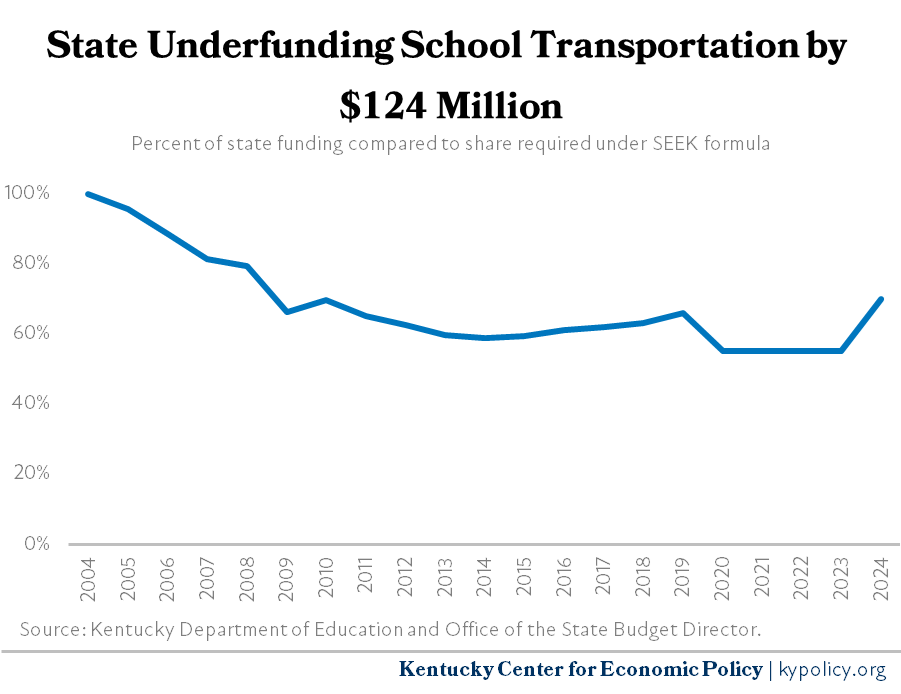

In addition to shouldering more of the burden to support the base SEEK formula, local districts must also make up for shortfalls in transportation funding. Despite statutory language requiring 100% state funding for estimated district transportation costs, the state has not fully funded the transportation formula since 2004. The most recent budget increased the funding level from roughly 55% to 70%, a modest improvement from prior years but still short of what the statute requires.22

A recent analysis from The Kentucky Council for Better Education estimates that an additional $1.2 billion investment this year would be needed to get SEEK funding back to what it was in inflation-adjusted 2008 levels.23

Mechanisms that improved school equity under KERA rely on adequate state funding

The growing shift from state to local funding for public education described above has increased inequities between poor and wealthy school districts. These inequities now arguably surpass those that existed in 1989 when the entire education funding system was declared unconstitutional in Rose v. Council for Better Education.24

In response to the Rose decision, the General Assembly passed the Kentucky Education Reform Act (KERA) and enacted major tax increases that raised over a billion dollars for public education. These revenue increases were key to ensuring the state had sufficient resources to establish and support the SEEK formula and ensure important strides toward equitable funding. Now, over three decades after Kentucky’s landmark effort to create more equity in education across the commonwealth, that progress has been erased.

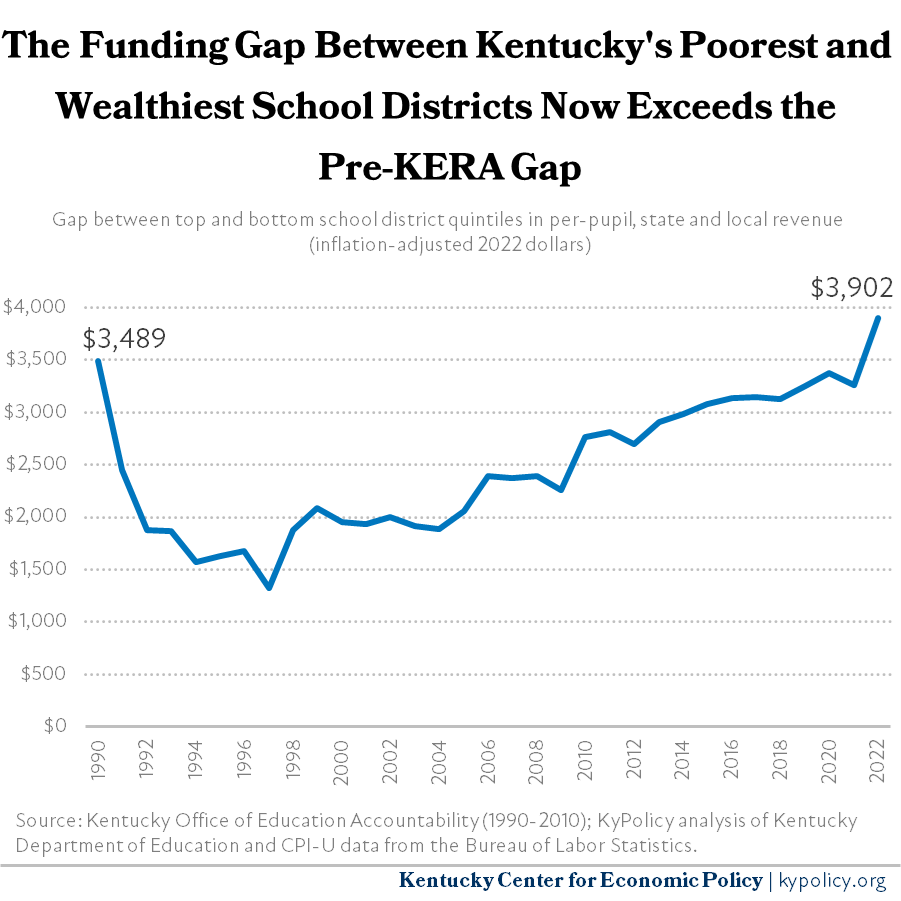

A recent KyPolicy report provided an update on the funding gap between wealthy and poor school districts using a measurement methodology previously utilized by the Office of Education Accountability (OEA). The report showed that in current dollars, the 2022 per-pupil funding gap between schools in the top and bottom quintiles was $3,902, which is $413, or 11.9%, more than it was in 1990, as illustrated in the graph below.25

The most significant drivers of these inequities are the chronic lack of state investment coupled with the drastically differing abilities of school districts to generate resources locally. In finding the system unconstitutional in 1989, the court explained:

The system of common schools must be adequately funded to achieve its goals… [and] must be substantially uniform throughout the state. Each child, every child, in this Commonwealth must be provided with an equal opportunity to have an adequate education. Equality is the key word here. The children of the poor and the children of the rich, the children who live in the poor districts and the children who live in the rich districts must be given the same opportunity and access to an adequate education. This obligation cannot be shifted to local counties and local school districts.

Teacher and staff shortages occur as pay and respect remain growing issues

There were no raises for teachers or school personnel mandated or specifically funded in the 2022-2024 state budget. Instead, it was up to local districts to stretch state and local dollars to cover often competing needs, and as a result, school employee salary increases in 2023 (the most up-to-date information available) were relatively modest, and were nonexistent in 10 school districts despite historically high levels of inflation.26 Among the districts with no raises are some of the smallest districts with the lowest property wealth, including at least two districts affected by relatively recent natural disasters.

A recent report from the OEA showed that Kentucky teachers are leaving their jobs at growing rates and fewer people are applying for teaching jobs and entering teacher training programs.27 Low pay and perceived lack of respect for the profession are among the major factors contributing to recruitment and retention challenges. Turnover is higher in schools with more low-income students and students of color, traits associated with fewer dollars and/or greater student needs for which more resources are necessary.

The report also documents major losses in “classified” staff, or employees whose jobs do not require a teaching certificate. Bus drivers and food service staff are leaving for the private sector and doubling their salaries on average. Compared to 2019, there are now 1,225, or 12.9%, fewer bus drivers; 7.3% fewer custodians and other operations staff; and 3.7% fewer food service staff.28

Federal funding helped supplement state funding and even fill in some gaps, but it is expiring

Kentucky received a significant amount of financial support for schools from federal COVID relief funds that were available to help offset COVID-related expenses, address student needs and begin making investments to help improve health and safety in the school environment. The vast majority of these resources were through a program called ESSER (Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief). These funds were distributed to schools based on the same formula as Title I funding, meaning that districts with a higher proportion of low-income students received more funds than wealthier districts.29 Districts have until Sept. 30, 2024, to spend remaining ESSER funds.30

Kentucky has been identified as one of 15 states facing the most complex challenges in addressing the funding cliff that will come when ESSER funds are gone. That analysis is based on three factors, including the amount of ESSER funds as a proportion of state education revenue (12.03% for Kentucky), how many districts serve students living in poverty (63% in Kentucky) and how many students are in a high-need district (51% in Kentucky). Since ESSER funds were distributed based on the Title I formula, within Kentucky those districts that serve a higher population of low-income students will be hit hardest by the loss of these funds.31

OEA recently reported that a total of 3,890 school positions are currently funded with pandemic dollars through ESSER. Of those, 2,133, or 55%, are existing positions for which other funding will have to be identified when the money runs out. Of the other 1,757 new positions created with ESSER funds, only 349 are expected to be retained when the monies end, meaning a loss of services that are currently being provided.32

Full-day kindergarten funding needs to be continued

Under state statute, the SEEK formula only includes funding for half-day kindergarten. Prior to 2021, nearly all school districts were providing full-day kindergarten but were partially funding it with local dollars. In 2021, for the first time, the state legislature included full-day kindergarten in SEEK so that all schools could offer a full-day program with less of a burden on limited local resources. The 2022-2024 budget also included this investment. Full-day kindergarten is associated with important academic benefits; studies have found that children who attend full-day kindergarten learn more in reading and math than children who attend half-day programs.33

Non-SEEK P-12 education funding includes few additional investments

In terms of funding for education programs outside of SEEK in the most recent budget, there were some increases for Family Resource and Youth Services Centers (FRYSCs) — which provide services for families to help address non-educational barriers to learning. These centers operate in schools where at least 20% of students are eligible for free and reduced-price lunches.34 The 2022-2024 state budget raised the funding amount from $184 per eligible student to $210. In addition, $7.4 million was provided for mental health professionals for schools. And Career and Technical Education funding nearly doubled, with a $127 million investment per year compared to $65 million in 2022. However, preschool and Extended School Services received no funding increases, and there continue to be no funds dedicated in the state budget for professional development or textbooks and instructional materials.

The Center for School Safety was funded at $13 million each year as in the previous biennial budget; school districts use these funds for School Resource Officers, alternative education programs, intervention services, security equipment, training programs, in-school suspension and community-based programs.35

Prior to the current biennium the School Facilities Construction Commission (SFCC), which assists local school districts with building needs, calculated the unmet facilities need to be over $6 billion.36 The Commission is responsible for extending offers of financial assistance to school districts for approved building or renovation projects that have demonstrated a reasonable local effort to provide adequate school facilities but still have unmet building needs.37 The 2024-2026 state budget authorized the SFCC to extend $85 million in new offers of assistance in anticipation of debt service availability during the biennium.

The budget also included an additional $170 million for Local Area Vocational Education Center Renovation grants and $27.6 million in General Fund dollars to meet commitments for school construction and renovation projects in HB 556 (2021).38 In addition, the General Assembly appropriated $4.3 million from the General Fund for repairs to facilities in four districts affected by the December 2021 tornadoes in western Kentucky.39

Still, the current unmet facilities need going into the 2024 legislative session is approximately $6.4 billion.40

Budget pressures mounting for school districts in next budget

As mentioned previously, the state’s school districts will be facing an “ESSER fiscal cliff” at the same time education costs have been rising with inflation, among other budget pressures. The $15 million in federal COVID funding (through the “GEER” program) that the governor allocated to FRYSCs has also been expended.41

In addition, it is possible that we may see state funding cuts to SEEK due to student attendance declines resulting from post-pandemic absenteeism. The funding formula as currently designed is based on average daily attendance. That means when there is a drop in students, districts receive fewer state funds even though their overhead and facility costs may be relatively unchanged. The poorer districts experiencing the biggest recent decreases in attendance rates are in eastern Kentucky counties already disproportionately harmed by state erosion of the SEEK per-pupil funding level, as well as recent flooding.42 More than half of superintendents responding to an OEA survey say they will have to cut staff if SEEK funding is reduced for this reason.43

Lawmakers are also considering a constitutional amendment in 2024 that would allow public tax dollars to go to private schools. This attempt to amend the constitution follows a unanimous state Supreme Court ruling in December that nullified the legislature’s law creating a program of state-funded tax vouchers for private schools. The ruling described how Kentucky’s strong constitutional commitment to public schools disallows public funding of private schools unless approved by a vote of the people.44

Early childhood education

Expanding preschool is an opportunity to strengthen early childhood education

Participation in preschool is associated with improved academic outcomes for children, and the benefits can even extend to better health and economic stability later in life.45 An analysis by the University of Kentucky’s Center for Business and Economic Research found there would be a $5 benefit for every $1 the state invested to expand the state’s preschool program.46 Universal preschool can help to provide greater economic and racial equity in school by ensuring all kids, regardless of barriers their families encounter, enter kindergarten with the skills they need to be successful.47

And yet, preschool is not guaranteed to Kentucky’s four-year-old children, with only $84.5 million appropriated for preschool to school districts in 2023 and 2024 (compared to over $250 million a year needed for universal preschool for four year olds).48 Eligibility for tuition-free preschool is currently restricted to four-year-olds in families with incomes below 160% of the poverty level ($48,000 for a family of four) and three- and four-year-olds with developmental delays and disabilities, regardless of income.49

Kentucky urgently needs to make a large investment in child care

Although funding and administration of child care assistance lies within the Cabinet for Health and Family Services and not the KDE, child care can be considered a part of the continuum of education because it has such profound effects on a child’s academic career and outcomes even into adulthood. Despite its importance to children, their parents and the broader economy, child care has not historically been a budget priority of the commonwealth.

However, in 2020 and 2021, Congress passed four laws that invested a total of $1 billion in Kentucky’s child care industry and made a significant difference in the availability, affordability and quality of child care, particularly the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), which accounted for three-quarters of that total. Specifically, these federal investments have greatly improved eligibility for assistance, provider reimbursement rates, help with starting new centers and the development of the child care workforce. And yet those funds are temporary, and either have already expired or will expire during the fiscal year 2025.

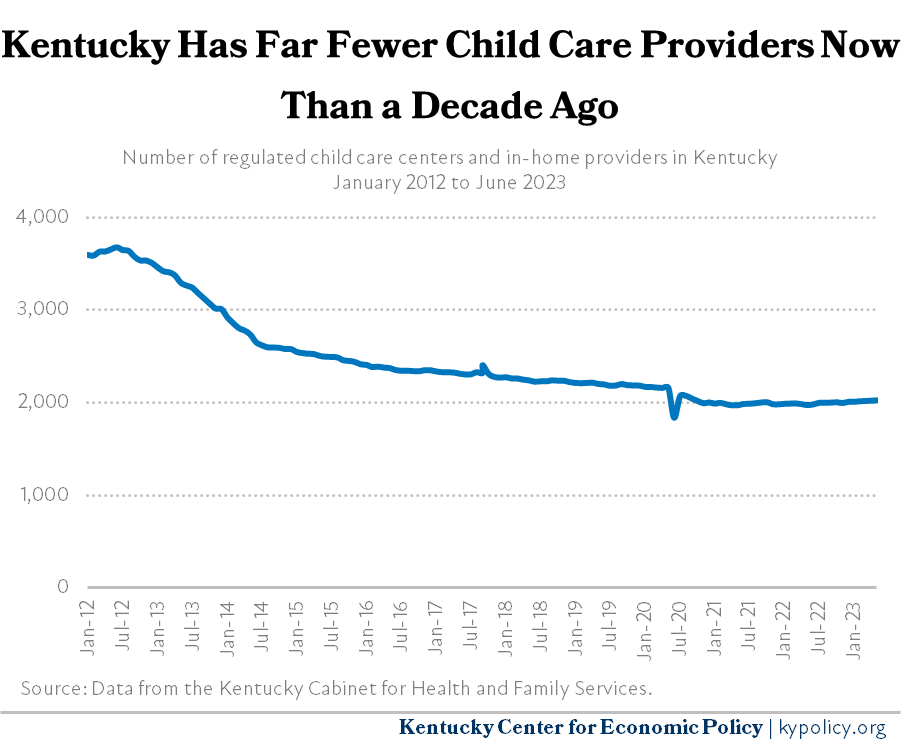

Past policy choices have made child care difficult for parents to find, recent federal aid has helped

One in three Kentucky counties is a child care desert, meaning child care is either unavailable or there are three or more children per child care spot.50 This disparity is largely driven by a decrease in the state’s child care providers, the number of which has fallen by 44.8% since the high-water mark in 2012.51 In 2013, a budget shortfall led the state to put a moratorium on new entrants to the state’s Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP), which provides help with child care costs for low-income families. When fewer children were enrolled in child care centers as a result, it was difficult for centers to operate and many closed their doors. Although this moratorium was lifted the following year, the trend never reversed, and the decline continued until 2020.52

The closure of child care centers only stabilized when the federal government began pumping a billion dollars into Kentucky’s child care system to sustain it during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic and consequent downturn.

The largest portion of ARPA’s child care investment in Kentucky came in the form of $470 million in quarterly sustainability payments. These funds are distributed to providers based on the number of children in care and the starting wage of the workforce (with $13-per-hour the top tier), as long as the center had been open for six months when the program began back in 2021. The average payment has been roughly $33,000 per-quarter per-center, and over $50 million per-quarter has been distributed. Those funds helped increase wages for the workforce, prevent higher tuition for families and even prevented some providers from closing altogether.53 The federal funding for those payments expired in September 2023, and while the state funded one additional payment for December 2023, there are no more sustainability payments scheduled moving forward.54

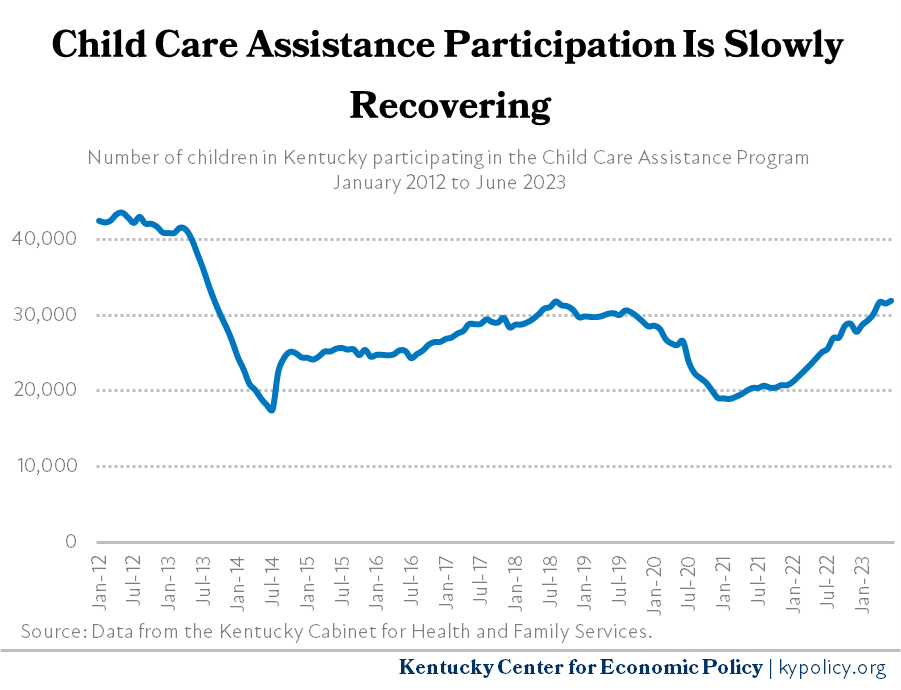

CCAP helps families with child care and federal investment made it much better

Today, nearly 32,000 Kentucky kids benefit from CCAP.55 Beginning in the 2016–2018 budget, the General Assembly included a $10.6 million increase in funding to raise the CCAP eligibility threshold for families from 150% of the 2011 federal poverty level (FPL) to 160% of the current FPL, or $42,400 for a family of 4 in 2021.56 More recently, through the large influx of federal funds, the eligibility limit was increased again to 85% of the state median income (SMI), which is around $66,000 for a family of four this year.57 Also, the new federal funding Kentucky started receiving since 2020 has allowed the state to waive family co-pays, which helps eligible families use CCAP without barriers once they are approved. Increasing the income eligibility limit and eliminating co-pays has helped CCAP participation begin to rise again.

Low state reimbursement rates to child care centers that care for kids participating in CCAP have made it difficult for providers to afford their operating expenses. In parts of the state where the share of children participating in CCAP is high, low reimbursements have historically contributed to child care shortages. Attempts to begin improving this situation started in 2016 with an increase of the reimbursement rate to providers by about $1-per-child per-day, and then again in 2021 with a $12 million appropriation to further increase the provider reimbursement by an average of $2-per-child per-day.58 Pandemic-era federal funds allowed the state to make a more meaningful increase in reimbursement rates. Reimbursement rates can now be up to $47-per-child per-day and are close to the recommended 75th percentile of market rates as laid out in the federal grant that pays for much of Kentucky’s child care assistance.59

These increases are small steps toward fostering the availability and viability of child care centers in Kentucky, but are still below what is needed to ensure that all of our child care is high-quality, which is when the best outcomes for children are achieved.60 The average cost for child care for a toddler in Kentucky is nearly a third of what it would cost to provide high-quality care, according to one study.61

The temporary federal funding has been used to address child care needs in other ways as well. In Kentucky, funding from ARPA specifically has been used to:

- Provide start-up grants to five employers to open new centers attached to their workplace,

- Provide smaller start-up grants to 62 individuals to open family care homes (regulated child care providers that operate out of a home),

- Provide start-up grants to 25 child care centers in a child care desert,

- Provide 581 child care employees scholarships to pursue early childhood degrees and certifications,

- And offer one-time facility improvement grants of up to $10,000 per center.62

The ARPA funds also allowed child care workers to bring their young children with them to the center where they work, without cost to the worker. The state decided to exclude child care employees’ income when determining their eligibility for CCAP, allowing centers to get paid for caring for the children of their workers. Between October 2022 and October 2023, 5,661 kids of 3,233 child care workers in Kentucky have been able to use this benefit in 1,019 child care centers.63 This expansion alone is a $22 million annual benefit.64 It proved to be an innovative solution to both retention issues for child care employees and child care affordability, for which Kentucky has received national praise.65

Federal funding is coming to an end, leaving a large fiscal cliff for Kentucky’s child care providers

These recent rounds of federal funding, particularly ARPA and the ways the state has deployed that funding, have shown what large investments can accomplish. These funds stopped the acceleration of center closures and began to address the low pay of the child care workforce and the quality of care provided. But there is no sign that Congress will continue that funding, meaning the General Assembly will need to make up for the $300 million annual shortfall this federal fiscal cliff from expiring ARPA funds will leave. States across the nation are exploring ways to address the end of the federal influx of funds for child care.66 The General Assembly will need to meet the full funding gap if it wishes to keep the status quo of our child care industry.

The new Employee Child Care Assistance Partnership Program that is currently being piloted in Kentucky is an attempt to plug part of that funding hole. But despite a large marketing campaign and a $15 million budget, only 113 children have benefitted from it as of October 2023.67 This employer-focused pilot by itself is not a sufficient solution to the coming funding crisis for our child care industry.

Postsecondary education

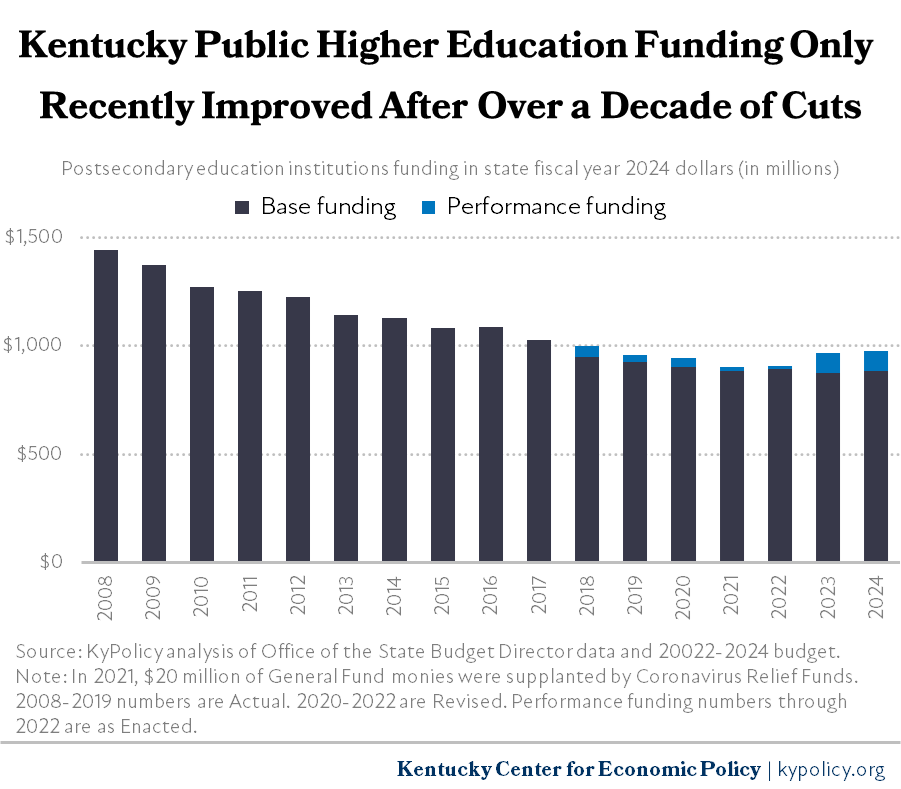

Kentucky’s investment in public higher education has also declined significantly in real dollars since 2008, with modest increases in recent years making up little ground. The cumulative effect is leading to significant challenges in affordability, quality and equity in Kentucky’s system of public higher education.

The 2022-2024 state budget increased funding for the state’s public universities and community colleges by an inflation-adjusted 6.3% between 2022 and 2023.68 However, the funding level in 2024 is still 32.4% lower than in 2008 in inflation-adjusted terms.69

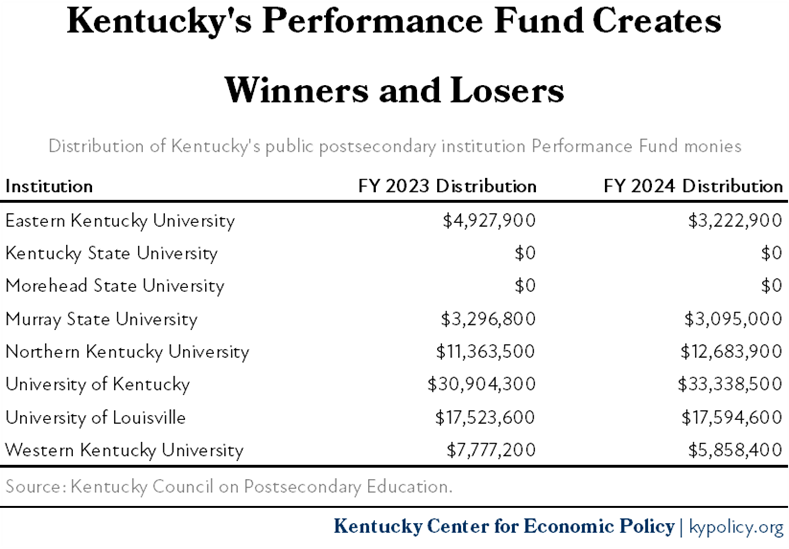

A growing share of Kentucky’s public higher education funding is distributed through the state’s performance funding models (there are two: one for the universities and another for the community college system). This model has exacerbated funding inequity between the state’s flagship institution and the smaller, regional universities which disproportionately serve more low-income students and students of color and are more likely to be situated in rural parts of the state. In the 2022-2024 budget, $97 million of state funding for public postsecondary education was distributed through the performance funding models for universities and community colleges in each year of the biennium; in contrast, this amount was $17 million in 2022.

In both 2023 and 2024, Kentucky State University (KSU), the state’s only public HBCU (Historically Black Public Colleges and Universities), and Morehead State University (MoSU), located in rural eastern Kentucky, received no performance funding dollars.70

Out of the 16 community colleges in the Kentucky Community and Technical College System, four institutions located in poorer parts of the state, out of the 16 total, received no performance funding dollars in 2023 and 2024: Big Sandy, Hazard, Henderson, and Southeast Community and Technical Colleges.

Several proposals for improving the higher education performance funding system are currently under consideration.71 For the university model, stakeholders’ proposals have included increasing the premium universities receive when low-income students graduate with a degree; modifying the small school adjustment so fewer funds available for MoSU and KSU are run through the performance model; eliminating the “degree efficiency” index weighting that rewards institutions when students graduate in a relatively short period of time; and adding a “new adult learner” metric that rewards enrollment, retention or completion of adult learners. Changes under consideration for the community college performance funding model include adding an “adult learner” metric and promoting equity by making adjustments for regional economic differences.

KSU faces unique funding challenges brought on by state underfunding

KSU faces additional financial challenges that have compounded over the past decade from state underfunding and the limited options school administrators have faced because of constrained resources.

Kentucky is one of 16 states that recently received a letter from the federal government notifying them that they have been underfunding their public HBCUs in violation of the law requiring equitable funding of land grant institutions.72 The letter indicates that for KSU the inequity in funding, compared to the state’s original 1862 land-grant institution the University of Kentucky, totals $172 million over the last 30 years. This restriction of resources has forced difficult choices on school leadership and is partly to blame for a revolving door of presidents and challenging working conditions for faculty and staff.

These problems came to a head in 2022. To address a financial crisis, the General Assembly passed HB 250 in 2022 loaning funds as a stop-gap measure to cover an immediate cash shortfall and instituting oversight measures.73 The legislation included a $23 million non-interest-bearing loan for KSU in fiscal year 2022 to help address financial instability from prior year deficits and structural imbalances, and appropriated $5 million in 2023 and $10 million in 2024 to be distributed based on meeting goals and benchmarks set out in a “management improvement plan.” An additional $1.5 million went to CPE for oversight in 2023.74

Lawmakers may further explore adding a public university in southeastern Kentucky, but report offers cautions

The 2023 Kentucky General Assembly directed CPE to study the possibility of adding public higher education capacity to southeastern Kentucky by 1) opening a new regional, residential, four-year university; 2) acquiring a private university; or 3) establishing a residential campus as a satellite of an existing regional public university.75 The study found that all of these proposed options are problematic in some way due in part to declining population and college enrollment in the region.76 The report suggests that without larger investments in job creation and economic development in the region, an expanded public postsecondary option may not be viable.

The cost of college is out of reach for many Kentuckians

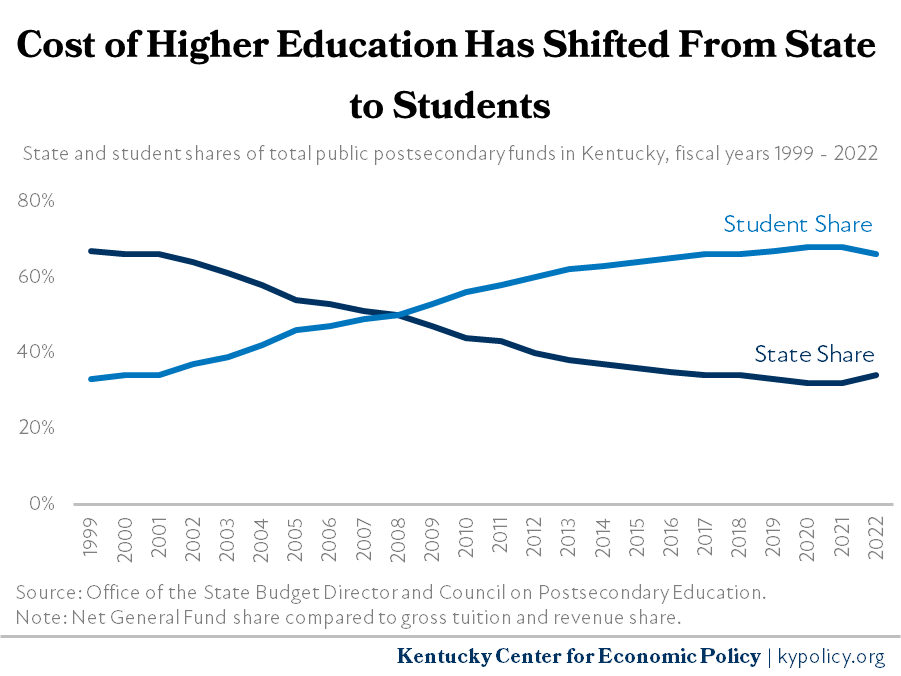

Cumulative budget cuts have also contributed to student cost increases at Kentucky’s public universities and community colleges, as institutions have increased tuition and fees in order to make up for some of the revenue losses from the state’s General Fund at the same time that fixed and other unavoidable costs – including inflation – have continued to increase. Since 2009, more than half of total public funds for higher education have come from student tuition and fees – making up 66% of public funding for Kentucky’s public postsecondary institutions in 2022, compared to 34% coming from the state’s General Fund.

Reductions in state funding have directly led to higher debt burdens for Kentuckians. Despite only small tuition increases in the most recent years, a growing share of individuals and families in Kentucky have taken on student debt as the cost of attending college has grown while wages and Pell Grant amounts have not kept pace.77 There is also a growing recognition that many Kentucky college students struggle to even meet basic needs.78

Supported by an increase in lottery revenues, the 2022-2024 state budget did include the full statutory funding for college financial aid, a 42% increase in funding for the College Access Program (CAP) need-based scholarships compared to the prior budget. Due to this increase in state funding for CAP, scholarship amounts have increased, which will help eligible students better cover the growing costs of college at the same time that wages and Pell grant amounts haven’t kept pace. While in 2022 the maximum CAP amount was $2,200 for a two-year college and $2,900 for a four-year institution, in 2023 it increased to $2,500 for a two-year and $5,300 for a four-year institution.79

Additional investments to address nursing shortage needed

Investments in higher education targeted to addressing the state’s nursing shortage are also needed. The Kentucky Hospital Association (KHA) convened a workforce committee to study the workforce shortage, and recently released a range of recommendations that include investing state funding in scholarships for healthcare students.80

Hospitals responding to the Kentucky Hospital Association’s 2023 workforce survey reported 10,776 full-time equivalent (FTE) vacancies, a vacancy rate of 15.3%.81 These hospital workforce shortfalls are expected to increase in the coming years as the aging population grows and several thousand nurses over the age of 55 are expected to retire. Reported vacancy rates for nurses were especially high, with registered nurses making up the largest group of direct care providers in hospitals. Reported vacancy rates were 19.7% for registered nurses, 20.1% for licensed practical nurses and 16.9% for nursing assistants.

Inadequate funding reduces quality and equity in public higher education in Kentucky

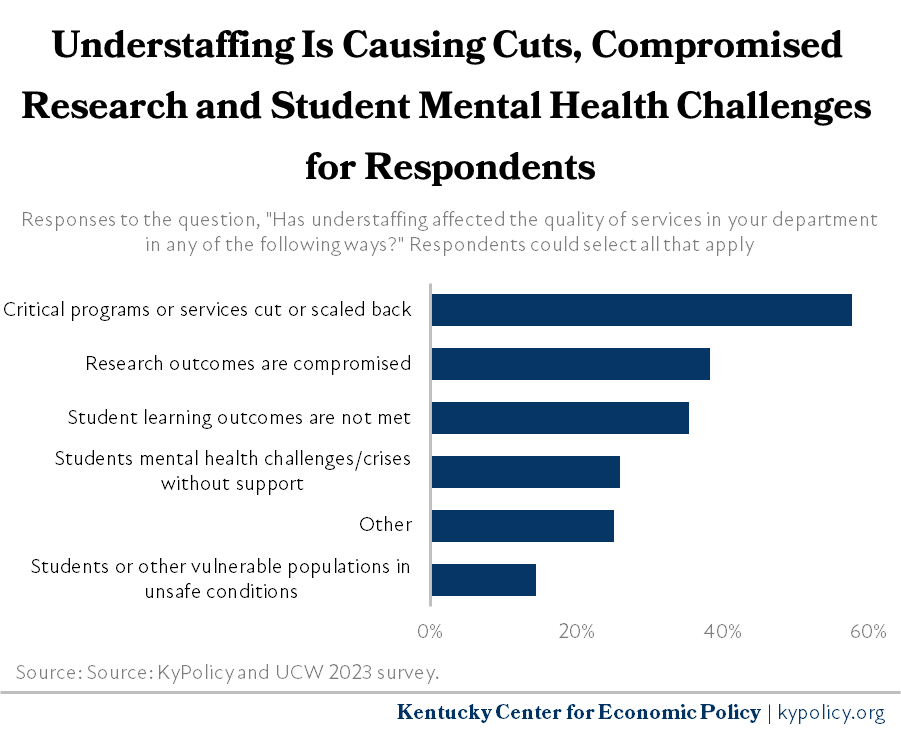

At the same time that tuition is much higher than it was historically at the state’s public universities and community colleges, and many students are going into debt but can’t afford to continue until they earn a degree, the quality of education being provided at these institutions cannot realistically be maintained while state funding levels decline.82 In order to balance budgets higher education institutions are reducing faculty and limiting course offerings, among other measures that reduce quality.83

A recent survey of Kentucky’s public higher education workforce conducted by KyPolicy and United Campus Workers (UCW), to which 1,367 faculty and staff responded, provides insight into how funding pressures are affecting compensation, workload, morale, job longevity and along with the ability to effectively conduct research, teach and support students, and provide services across Kentucky communities.84 These conditions are not conducive to sustaining high-quality educational programs, a diverse student body, enrollment growth, research activity and academic success, particularly for first generation college students, students from low-income family backgrounds and students of color.

The survey found that job quality is worsening on public higher education campuses across the state, resulting in declining student and research outcomes:

- Over half (53%) of respondents selected pay as their top concern, with nearly one in three respondents saying they have not received a pay raise in the past year and two in three selecting pay as the number one consideration as to whether they will leave their job.

- 66% of respondents said their department is understaffed, and three quarters (77%) said staffing levels are worsening or not getting better. Respondents said lack of funding and low pay making it harder to recruit and retain staff are primary drivers of these staffing shortages.

- 63% of faculty respondents said their departments have cut tenure-track positions, and over half (55%) said they have lost administrative support.

- The cumulative result of these and other job quality issues is that seven in 10 respondents said they have considered leaving in the past year for reasons other than retiring.

- Faculty reported that a loss of administrative support is leading to more of their time spent on administrative paperwork (83%), recruitment efforts (57%) and supporting students through mental health challenges or crises (37%).

- 58% of respondents said the challenges they face are leading to critical programs or services being scaled back or cut altogether.

- One in three respondents reported that research outcomes are being compromised and that student outcomes are not being met.

Physical buildings on campus are also deteriorating, creating unhealthy and even unsafe environments for some students. The 2022-2024 state budget included a number of capital projects on public higher education institution campuses.85

Federal Higher Education Emergency Relief funds helped some but have ended

Kentucky was awarded $942.2 million in Higher Education Emergency Relief COVID relief funds.86 The three largest categories of funding awarded were $376.4 million to students, $481.8 million to support public and private higher education institutions and $28.9 million was specifically for HBCUs. This funding expired in June 2023, other than money allocated to schools that received a one-year extension. As of Sept. 30, 2023, 95.5% of the total amount of Kentucky’s awarded funds had been spent.

Human services

Higher wages are slowing turnover in Kentucky’s child welfare and family support systems

The Department of Community Based Services (DCBS) is the largest agency in state government. It provides social services ranging from the child welfare system to public assistance caseworkers. Recent budgets have begun to address the social worker shortage and workload burdens through raises, and these investments in recruitment and retention are working. Adequate pay and manageable caseloads are not just necessary for the workers but are critical to ensuring children are removed from their homes only when absolutely necessary, family preservation is prioritized, and errors are avoided. Any time a child is removed from their home is a traumatic experience with ripple effects throughout life, and having a well-trained, experienced and fully staffed child welfare system can mitigate that harm.

The starting salary for all social workers was increased from $33,644 to $50,754 because of funding improvements in the last budget. Several other salary improvements have been implemented as well: social workers in Jefferson County received a $4-per-hour locality premium in recognition of their higher cost-of-living, and a $5-per-hour shift premium for work outside of the normal work day. On top of these changes, DCBS created “critical incident leave” for when social workers are involved in especially traumatic cases. The department also now offers special training programs and flexible workplace and hours policies. All these efforts have led to a significant reduction in turnover – falling from 40.5% in 2021 to 33.9% in 2022, and even lower in the first half of 2023.87

To ensure Kentucky continues to slow its revolving door of social workers and maintains a quality workforce for Kentucky’s kids and families, additional cost-of-living raises will be critical in the next biennium. Front-line public assistance caseworkers in the Division of Family Supports also have high rates of turnover, and, until recently, had very low pay. Improvements from the last budget and HB 444 from the 2023 legislative session helped slow turnover in that workforce as well.

Evidence suggests that robust social services play a role in helping Kentuckians get and stay healthy. A study published in Health Affairs shows that a higher ratio of spending on social services and public health services yields better health outcomes, particularly for conditions such as asthma, adult obesity, poor mental health, lung cancer, heart attacks, Type 2 diabetes and even mortality. While the study did not suggest an ideal ratio, it did suggest that policymakers need to think of social service spending as a form of public health intervention.88

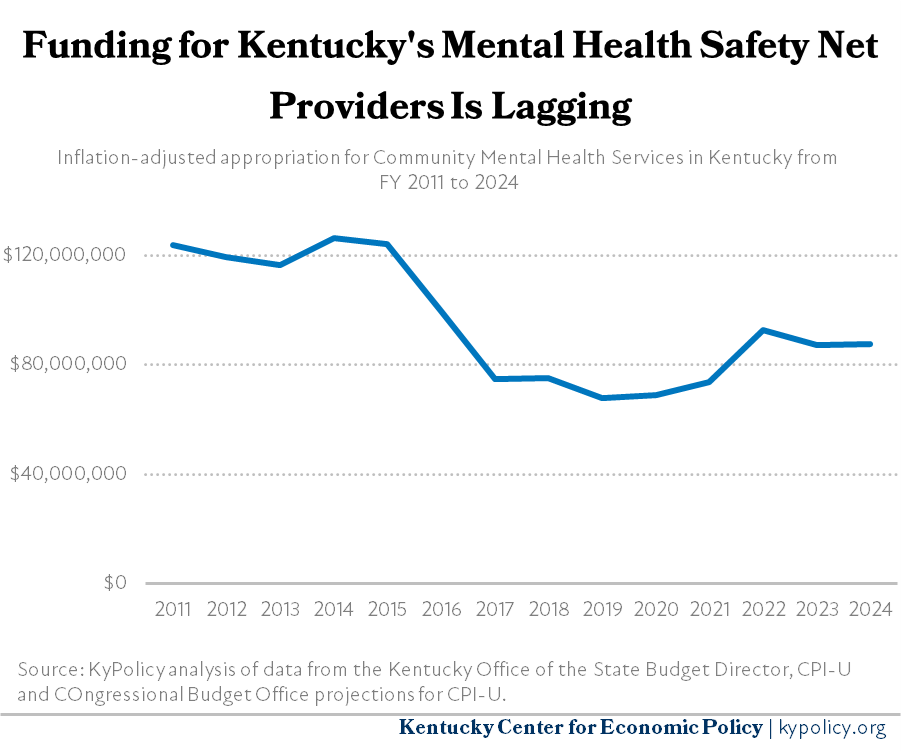

Mental health services dealing with decreased funding

Kentucky’s Department for Behavioral Health, Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities provides a wide range of services for addiction treatment, community living for dependent adults, long-term institutional care for those with severe needs and outpatient mental health services. Kentucky’s 14 Community Mental Health Centers (CMHCs) are funded through this department, and while Kentucky was the first state to provide a system of mental health safety net centers, the state has failed to maintain sufficient funding. Over the past decade, inflation-adjusted appropriations for CMHCs have fallen. The decline was slightly reversed only recently due to new funding for the 988 suicide crisis hotline, which was implemented last year for the first time in Kentucky, and for increased pension contributions. But the latter dollars go to pay increased state liabilities and not to expand mental health services.

Senior feeding program waitlist was temporarily eliminated with federal funds that are now expiring

In addition to Medicaid services for people with disabilities, which are discussed in the following section of the report, Kentucky also cares for people who are aging or have a disability through the Department for Aging and Independent Living (DAIL). DAIL administers both federally and state-funded programs that help to keep dependent adults out of institutionalized care. One important service DAIL provides is the state’s senior feeding program, which provides meals to Kentuckians over 60 through the Area Agencies on Aging and Independent Living (AAAs), including meals in senior center dining rooms and meals delivered to home-bound Kentuckians with low incomes.

In the previous budget, the state allocated $21.7 million in ARPA funds to eliminate the waiting list for those services.89 That allowed DAIL to expand the program to provide over 2.5 million meals to an estimated 156,700 older adults in 2023.90 It also allowed the AAAs administering these programs some flexibility to get more meals to more seniors by implementing drive-thru meals, increasing deliveries, expanding the number of days meals are available and ultimately eliminating the waitlist of 36,000 older adults in Kentucky. Those funds will expire in 2024, so a minimum of $14.4 million in General Funds would be needed in order to prevent the build-up of another waiting list.

Medicaid

Medicaid played a critical role during the pandemic, but federal aid has expired

Medicaid is the second-largest General Fund appropriation in the state budget, behind only P-12 education. It makes up roughly one in eight General Fund dollars and one in three dollars the state spends overall (with the latter including federal dollars that flow through the state budget).91 Investments in health care create long-term dividends in the economy and well-being of the state. One of the starkest examples of Medicaid’s power is the huge decline in uninsured Kentuckians, with the rate of uninsured falling from 14.3% in 2013 (the year before Medicaid expansion) to 5.6% in 2022 (the most recent year for which data is available) — a 61% decline overall. Medicaid’s ability to cover groups that have had historical and structural barriers to coverage is profound, virtually erasing the coverage disparity between white and Black Kentuckians in 2022, for example.92

The impact of Kentucky’s Medicaid program on the state budget are almost entirely driven by three factors:

- The number of people who are covered,

- The cost of providing medical care and

- The federal share of overall Medicaid expenditures known as the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP).

Kentucky has two different Medicaid FMAPs:

- One for eligibility categories that existed prior to the Affordable Care Act, such as pregnant women, children, people with disabilities and older Kentuckians who are indigent, which is referred to as traditional Medicaid, and

- A second FMAP for all other Kentuckians covered by Medicaid who have incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level, often called Medicaid expansion.

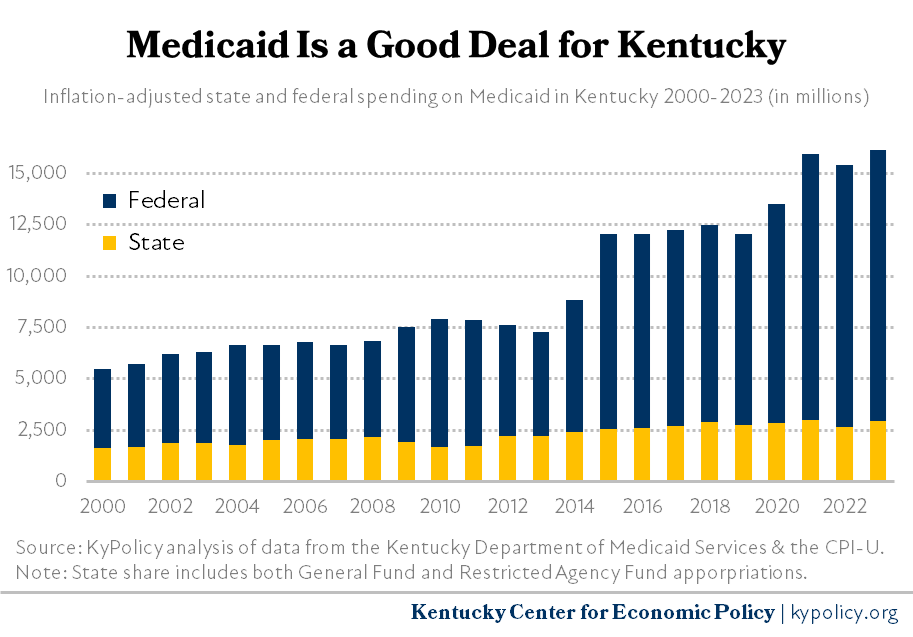

Because Medicaid is funded through an FMAP, it is a great financial deal for the commonwealth given the federal government pays for such a large share. As of 2023, although the state paid $2.9 billion in combined General Fund and restricted agency funds for Kentucky’s Medicaid program, the federal government paid $13.2 billion. This means that for every state dollar invested in Medicaid in 2023, the federal government invested $4.48.93

Since 2016, the final year that the federal government still paid for all of the state’s Medicaid expansion, General Fund spending on Medicaid has fallen an inflation-adjusted 2.0%, while federal spending has increased 39.7%.

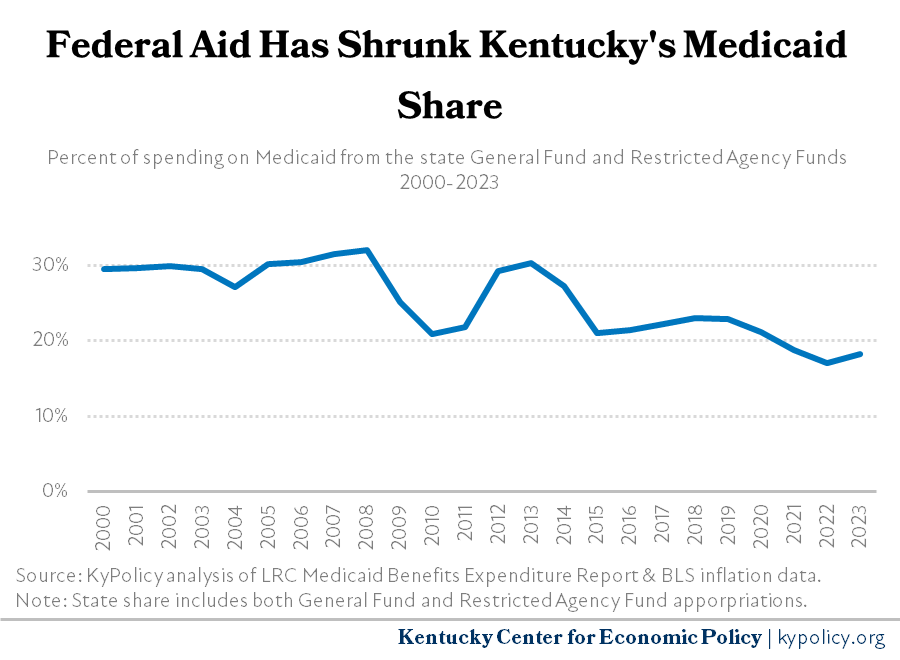

As previously mentioned, Kentucky has two different FMAPs and they are both a significant determinant for the overall cost of Medicaid to the state. The first of these is for Medicaid expansion which is the more generous and more stable of the two. Kentucky has paid 10% of those costs since 2020, which came out to $562.8 million in state fiscal year 2023.

The traditional Medicaid FMAP, on the other hand, depends on the economic well-being of each state, and ranges from around 50% to just under 75%. Due to the state’s high poverty rate, Kentucky’s traditional Medicaid FMAP is 71.8% as of federal fiscal year (FFY) 2024.94 But because of the COVID-19 pandemic and economic downturn, the federal government paid for an additional 6.2 percentage points of total costs from 2020 to June of 2023. That resulted in a traditional Medicaid FMAP of 80.3% in state fiscal year 2023.

This extra federal spending was worth approximately $621.8 million in FY 2023 and since 2020, when the temporarily higher FMAP went into effect, the cumulative benefit to the state has been $2.3 billion.95 But the debt ceiling agreement enacted by Congress early in 2023 resulted in a planned, gradual reduction in the enhanced FMAP, so that by January 2024 it will phase out entirely, leaving Kentucky with its standard 71.8% FMAP for traditional Medicaid. In total, Kentucky’s blended FMAP (the combination of expanded and traditional Medicaid) was approximately 81.8% in state fiscal year 2023, with Kentucky’s General Fund and restricted agency funds paying the remaining 18.2% — the second lowest in at least the past 21 years. But starting in 2024 and certainly in the next biennium, the 6.2 percentage point increase for traditional Medicaid will be gone, leaving Kentucky with a share of closer to the 21% to 22% it had been prior to 2020. The Kentucky Department of Medicaid Services reports needing an additional $395 million in fiscal year 2026 to account for the loss of the 6.2 percentage point federal increase, higher prescription drug costs and higher reimbursement rates in long term services and supports.96

While much has been made of the cost of the 2014 expansion of Medicaid eligibility in Kentucky, Medicaid expansion doesn’t comprise much of overall Medicaid spending. General Fund spending on Medicaid expansion totaled $562 million in state fiscal year 2023, far less than the $2.4 billion in General and Restricted Agency Fund spending on traditional Medicaid.97 This lower spending level is because there are more Kentuckians enrolled in the traditional forms of eligibility (the majority of whom are children), the federal government covers less of the cost of traditional Medicaid than for expansion, and expansion participants cost less per-person to cover than those enrolled in traditional Medicaid, who are more likely to have a disability or are older requiring greater medical care.

The state has resumed determining if Kentuckians on Medicaid are eligible, and many are losing coverage

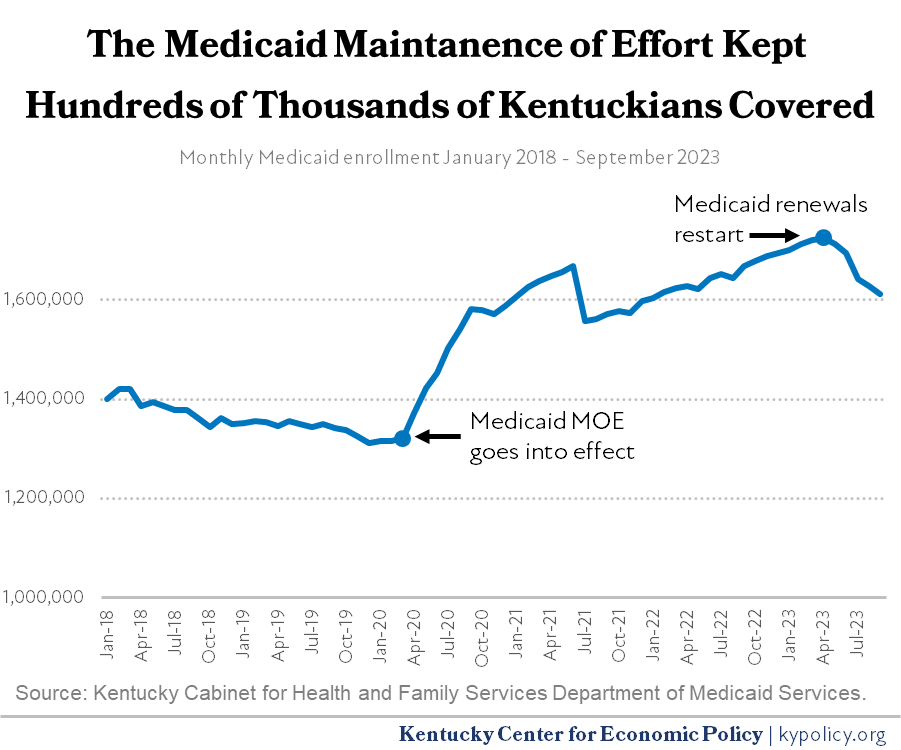

When the pandemic-triggered economic downturn led to tens of thousands of Kentuckians losing employment-based health coverage, many turned to Medicaid for their health coverage. To ensure these Kentuckians did not see coverage disruptions during such a tenuous time, the 6.2 percentage point increase in federal funding came with a continuous eligibility requirement, barring the state from terminating coverage for anyone unless they moved out of state or asked to have their Medicaid coverage ended.

This requirement was incredibly successful in keeping people insured, covering 400,000 additional Kentuckians between March 2020 and April 2023. However, that mandate came to an end in April of 2023 with the expiration of the federal Public Health Emergency (PHE), and the state once again began determining if those covered by Medicaid are still eligible. The state has 12 months to initiate that process for 1.7 million Kentuckians and must finish acting on redeterminations within 14 months. This process has resulted in 90,000 fewer people on Medicaid than at Kentucky’s peak in April of 2023.

Recent Medicaid spending growth is largely due to special programs that pay hospitals more

Total Medicaid spending growth was largely driven by a dramatic increase in spending from Medicaid’s restricted agency fund (63.4%).98 This increase was to pay for three General Assembly-created “directed payment” programs, which mostly increase payments to hospitals so that Medicaid payments are similar to commercial rates.99 Collectively, the new directed payment programs increased total Medicaid spending by $3.0 billion out of Kentucky’s $16.6 billion total budget in FY 2023 in a combination of restricted agency and federal funds.

It is important to note that this large increase in Medicaid spending due to the directed payment programs will not have a budgetary impact on the General Fund because the programs are being paid for through higher provider taxes (which the providers lobbied for) that comprise part of Medicaid’s restricted agency funds.

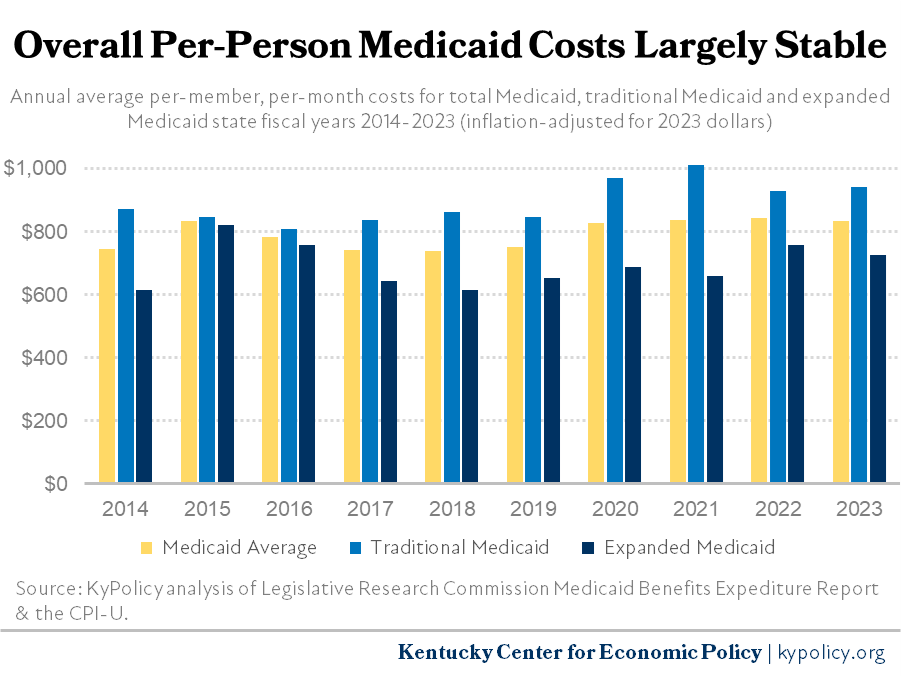

Medicaid enrollee costs have largely stabilized

Besides the FMAP and projected enrollment, the cost of providing medical care is an indicator of future budgetary needs, and that has largely stabilized in recent years. The per-member, per-month average cost fell an inflation-adjusted 1.0% between 2022 and 2023. Traditional Medicaid costs grew 1.4% year-over-year, rising from an inflation-adjusted $929 to $942. Meanwhile, the cost of covering each Medicaid member under the expansion actually fell 3.9%, from $757 to $728.100

In the 2024-2026 Budget of the Commonwealth, state lawmakers will need to appropriate for the increase in the state share of Medicaid spending, while accurately accounting for the reduced enrollment – both stemming from the end of the PHE. Barring another economic downturn (when, historically, Medicaid enrollment grows the most), enrollment growth itself will likely not be a major driver of cost during the next biennial budget.

Improvements needed for programs that provide Kentuckians with care at home and in their community

Traditional Medicaid pays for in-home care for individuals with significant health care needs, such as intellectual or developmental disabilities and brain injuries, through 1915c waivers, sometimes called Home and Community Based (HCB) service waivers. These programs are vital to supporting Kentuckians with disabilities so they can stay in the community rather than in nursing homes or state-run institutions, which are more expensive and less desirable for many people. As of July 2023, Kentucky had 33,412 spots for these waivers filled by 31,686 Kentuckians.101

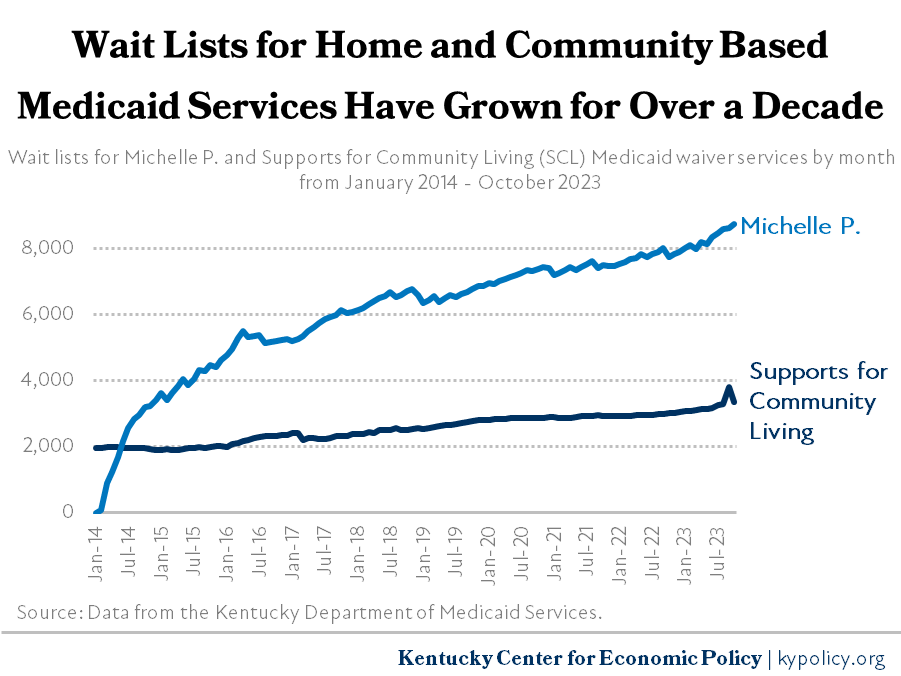

One major issue for these programs is that waiting lists have grown by thousands, while only 200 slots have been added in the previous three budgets. This growth in the waiting lists was driven entirely by increases in Kentuckians seeking services through the Michelle P. (community and home-based care for Kentuckians with intellectual or developmental disabilities) and Supports for Community Living (SCL) programs. Michelle P. in particular has had a significant increase in Kentuckians waiting for its services — in January 2014 it had no waiting list, but now it has swelled to 8,740 as of October 2023.102 Additionally, for the first time in the history of the program, the HCB waiver briefly had a waiting list in June of this year before the new fiscal year began and previously vacated spots opened up. In total, a lack of sufficient state funding led to 12,088 people waiting for the state to tell them if they can receive services from the Michelle P. or SCL waivers by the end of fiscal year 2023.103

Michelle P. and SCL services are costly, at $36,000 and $97,700 per slot per year respectively, so reducing or eliminating the waiting list is a significant budget expense.104 Another budgetary need for these programs is addressing chronically low reimbursement rates that have led to difficulties in hiring and retaining a qualified workforce. The previous budget appropriated a 10% increase in the reimbursement rate per fiscal year for all the waiver programs except Model II.105

Disability advocates are calling for an end to these waiting lists. One proposal is to cover all spots through an eight-year window, costing approximately $58.6 million in additional funds each of the eight years, and creating 1,590 new spots each year. Doing so, would draw down $152.1 million in additional federal funds coinciding with each year’s increase in state investment.106

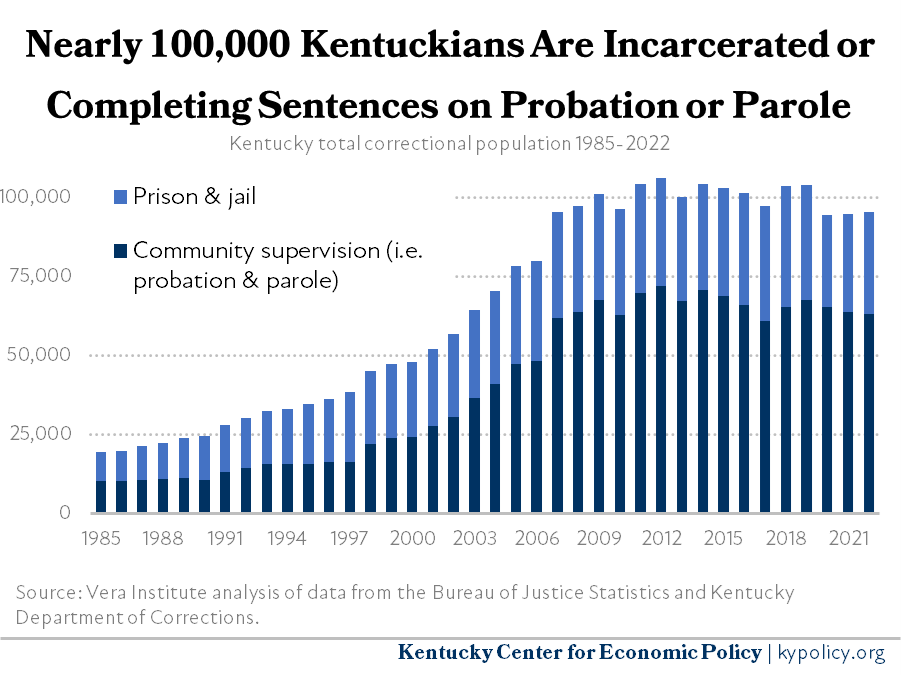

Criminal legal system

If Kentucky were a country, it would be the seventh most incarcerated place in the world, with almost 30,000 people in a jail or prison on any given day. Many of those individuals have not been convicted of a crime but remain incarcerated because they cannot pay bail. There are also over 63,000 people on probation or parole.107 Unlike other areas of the state budget, where increased investment usually leads to improved quality of life for Kentuckians, spending more to incarcerate and supervise people often has the opposite effect. Incarceration is expensive – the Department of Corrections (DOC) General Fund appropriation for the current fiscal year is $722 million – money that could be better spent on services communities need and in efforts to prevent crime and the poverty that is often criminalized.108

Research shows increased punishment and longer sentences do not make us safer.109 Involvement in the criminal legal system is harmful to individuals, their families and the greater community. When compared to the general population, individuals who have been incarcerated are in worse physical and mental health and experience a lower life expectancy.110 Regardless of sentence length, people who are incarcerated also experience greater financial instability and higher rates of substance use disorder and overdose upon release.111

These negative consequences disproportionately impact Black Kentuckians, who make up only 7.7% of the state population, but 21% of the prison population.112 Kentucky women are also disproportionately impacted, as Kentucky incarcerates women at a higher rate than any other state in the country.113 Most of these women also have minor children.114

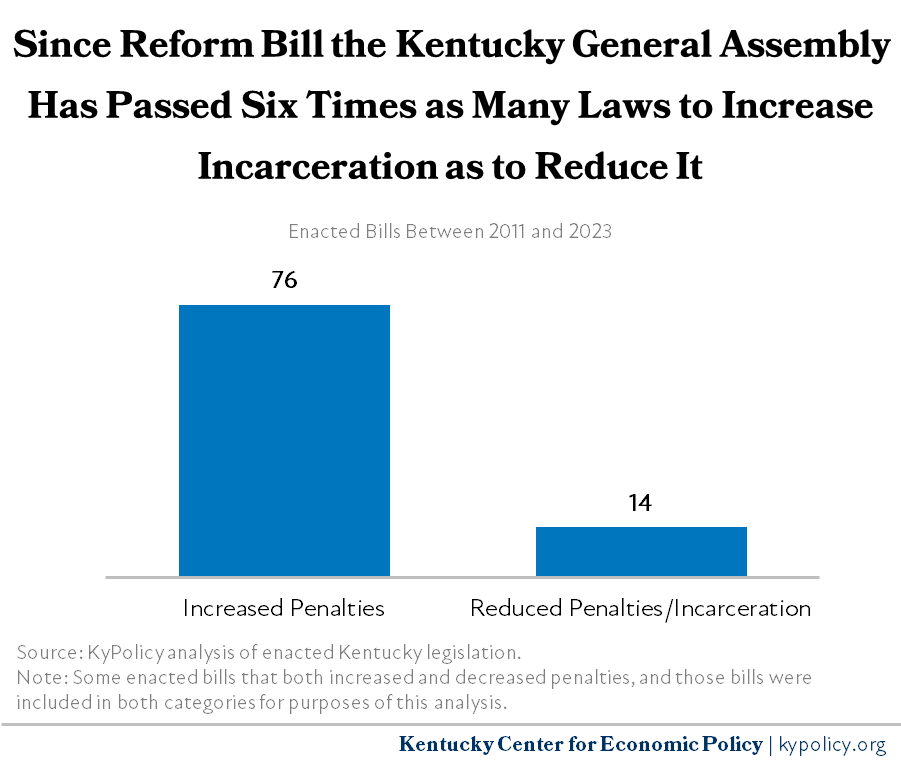

In the past 12 years, the General Assembly passed six times as many laws that increase incarceration than to reduce it – including last session where the General Assembly expanded who is eligible for the death penalty and created new crimes of Hazing and Vehicular Homicide.115

State prison populations, system financial needs on the rise

State appropriations to the Department of Corrections (DOC) have been steadily increasing over the past few years due to a higher number of incarcerated individuals and increasing operating costs. For fiscal year 2024, the DOC General Fund appropriation in the state budget was $722 million, and an additional $30 million was appropriated during the 2023 legislative session to increase starting pay for correctional officers to $50,000 and to provide retention incentives for existing employees.116

Included in this appropriation is debt service to support two significant projects, including the expansion of the Little Sandy Correctional Facility by 816 beds and the construction of a new psychiatric treatment unit building on the site of the Blackburn Correctional Complex in Fayette County.117 These two projects are intended to replace the Kentucky State Reformatory, located in Oldham County, which has been severely understaffed, and is in need of extensive repairs.

The 2022-2024 biennial budget also directed the DOC to produce a strategic master plan for its prisons and to present the plan to the Interim Joint Committees on Appropriations & Revenue and Judiciary by July 1, 2023. That plan identified over $277 million in immediate capital needs for the next biennium, primarily related to maintenance.

The number of incarcerated people in DOC custody decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic, but now numbers are on the rise again and have exceeded the 2022-2024 prison population forecast, on which the budget was based, in every month since October of 2022. Prison population forecasts for the 2024-2026 budget predict additional increases over the next biennium.118 Unlike most states, Kentucky houses nearly half of those serving state sentences in local jails, so population forecasts include individuals in DOC custody in jails as well as prisons.119

The cost of incarceration in a state prison ranges from $85.41 to $204.16 per day, with an average cost of $105.23 per day.120 In contrast, the average payment by DOC to a local jail is $40.11 per day for people not enrolled in substance use programming and $50.11 for those who are.121 Therefore, it is financially beneficial to the state to house Kentuckians convicted of felonies in county jails, and to pay the county to incarcerate them. Even though this results in severe crowding in local jails, many counties rely heavily on this revenue to fund their local operations because the cost to house someone serving a state sentence is less than what the jail is paid by the state, resulting in a profit for the jail.122 These perverse incentives have led many counties to build larger jails to house more individuals in state (DOC) custody serving felony sentences, or simply overcrowd their existing facilities. The ability of counties to profit off of people who are ultimately convicted of felony offenses also makes it more difficult to advocate for defelonization of certain offenses such as drug offenses, or for local law enforcement and prosecutors to charge only misdemeanor offenses.123

There has been progress in drug policy in recent years, but much more is needed to curb incarceration harms

Kentucky’s current “tough on crime” approach is especially harmful when it comes to helping Kentuckians who are battling substance use disorder. In 2023, over a quarter of all Kentuckians serving state sentences were serving for a drug-related offense (not including those detained pretrial or those serving misdemeanor drug-related sentences in county jails).124 And while attitudes around drug policy are evolving – as seen with the passage of legislation permitting medical cannabis and fentanyl testing strips in the 2023 legislative session – there is still more to be done to ensure Kentuckians experiencing substance use disorder receive the help they need rather than prison or jail time.

Investment in drug policy reform and treatment is especially critical given the overdose crisis plaguing the nation and our state. Last year, over 2,100 Kentuckians lost their lives to an overdose. The highest rate of overdose deaths are in rural counties, and fentanyl remains the most common cause with its presence in over 70% of overdose cases. While overall overdose rates have decreased recently, the rate is rising among Black Kentuckians.125

Fortunately, funding is available for investment in drug policy improvements and programs through Kentucky’s nearly $900 million share of opioid settlement monies from pharmaceutical companies responsible for the opioid crisis. These settlements were finalized at the beginning of 2022, and the monies will be periodically distributed to the state over the coming years.126 Distribution of the funds is overseen and monitored by the Kentucky Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission, with 50% going to the state, and the remaining half going to local governments.127 Thus far, over $32 million has been awarded in grants to various organizations – 23 prevention grants and 36 treatment and recovery grants.128

Investing these funds wisely can lead to decreased incarceration and lives saved. Potential effective uses include expansion of medication assisted treatment (MAT), increased harm reduction programs such as syringe exchanges and Naloxone distribution, establishment of overdose prevention centers and expansion of wrap-around services for those in active addiction or recovery.129 In addition, there is a need for investment in social services known to stabilize communities and promote recovery, such as access to affordable housing.

An award of $10.5 million in opioid settlement funding is going toward the implementation of 2022’s Senate Bill (SB) 90, which aimed to reduce incarceration and criminal system involvement by implementing an 11-county, four-year “conditional dismissal” pilot program. This program diverts people with mental health and substance use disorders who meet the eligibility requirements from the court system, instead providing them with supports and services in the community.130 As of Nov. 3, 2023, the program had begun operating in eight of the 11 pilot counties.131

Opportunity to invest in reentry supports for Kentuckians leaving incarceration

In addition to drug policy reform, Kentucky lawmakers have an opportunity to better support those who are returning from incarceration. Improvements to reentry services would help people reintegrate into their communities and find employment and other services that lower the rate of recidivism. Reentry support is essential with 12,821 Kentuckians returning home from state prison in 2022 alone, and with at least 95% of people who are sentenced to serve time in prison returning home one day.132 While Kentucky’s recidivism rate is at a historic low of 21.75%, more can be done to ensure it continues to drop.133

Kentucky advocates have long called for a better process for those released from incarceration to obtain state identification cards (IDs).134 Having a photo ID is a necessity to access services and employment opportunities to rebuild lives after incarceration.135 Currently, state law requires photo IDs be provided to people upon release, but the DOC and Department of Transportation lack needed funding to provide this service.136 A 2021 pilot program funded by charitable dollars issued hundreds of IDs to Kentuckians exiting the DOC.137 The Warren and Russell County jails have established similar programs.138However, to expand the impact of these programs and make them permanent, Kentucky needs to fund a statewide ID program to be operated at every state prison and local jail for those who are in need of a valid photo ID upon release. While the costs of the actual IDs are relatively low, a few million dollars per year investment would be needed to get ID programs running at all state prisons and local jails.