Incarceration is harmful to individuals, families and communities, yet Kentucky incarcerates 40% more people per capita than the United States average, which is more than 5 times larger than other wealthy countries.1 Work groups, research studies, special legislative committees and numerous pieces of comprehensive legislation filed over the years have sought to reduce incarceration and its negative impacts. For the most part, however, these efforts have resulted in only minor, short-term changes. Thus, the upward trend of incarceration in Kentucky continues, even as several other states have made meaningful changes that are beginning to reduce mass incarceration.2

Note: This report is available as a PDF here.

Perverse financial incentives resulting from the unique state/local structure of our corrections system are a major cause of Kentucky’s failure to reduce incarceration and overcrowding where other states have succeeded. In the face of tight budgets, the state has shifted costs to counties in order to reduce its own burden, and in fact pays cash-strapped counties to house people in state custody. At the same time, counties are legally and fiscally responsible for the incarceration of those who are held pretrial or on misdemeanor sentences, with related costs determined not by the counties themselves but by state laws, state decisions about funding the justice system and separately-elected judges and prosecutors.3 To respond to those fiscal responsibilities, some county jails rely on the economies of scale created by overcrowding including the extra revenue that comes from holding people in state and federal custody and from charging fees to those who are incarcerated.4

This arrangement incentivizes counties to expand incarceration — including by building larger jails and crowding them — in order to offset their costs. The result is a vicious cycle of lives harmed by incarceration, pressure to keep the pipeline of incarcerated people full, and rising public costs for corrections driving out other investments that could better address the root causes of the challenges communities face in the first place. And while incarceration is often framed as a public safety solution and jail expansion as a necessary accommodation, jail expansion is actually a driver of mass incarceration, with harmful fiscal and human consequences.

Another consequence of this vicious cycle is that while county governments advocate for policy changes that would lower their costs by reducing pretrial incarceration, they typically oppose sentencing reforms that would reduce the number of people serving felony sentences that the state pays county jails to incarcerate. In other words, both pretrial policy changes and sentencing policy changes would reduce incarceration, but the latter would negatively impact county jails’ bottom line by limiting their revenue-generating opportunities, while the former would benefit it.5

This report provides an in-depth look at the fiscal complexities of jail funding in Kentucky that stymie progress on much-needed policy changes. While much has been written about the inconsistent and often poor living conditions of Kentucky’s county jails, as well as the collateral consequences of incarceration, this report focuses on how the broken system we use to pay for our jails contributes to the poor living conditions, fuels the construction of bigger jails and ultimately contributes to the lack of success in making systemic changes.6 It is based on state and local data, as well as in-person visits and conversations with local justice system actors in several rural Kentucky counties (rural areas are where the majority of jail incarceration in the state occurs). We begin by describing the historical, legal and fiscal context for why Kentucky’s jails are overcrowded and the barriers to reforms. The next section takes an in-depth look at these issues in several county jails. The report closes with policy recommendations to reduce incarceration while addressing counties’ fiscal constraints.

Who is incarcerated in Kentucky jails?

Kentucky is one of two states, along with Louisiana, that are unique for the extent to which they incarcerate such a large share of the individuals who are in state custody in county jails. In Kentucky, close to half of individuals serving felony sentences for the state do so in county jails, the reasons for which will be discussed below.7

Unlike Kentucky’s 13 state prisons, and 1 privately run prison, where everyone is serving a felony sentence, the people incarcerated in Kentucky’s county jails are a much more diverse group, including:

- Individuals that counties are required by law to house and pay for who are either awaiting trial or serving time for a misdemeanor conviction (no longer than 12 months);

- Individuals in “controlled intake” status who have been sentenced and are awaiting transfer to a state facility; and

- Individuals that the county has no legal obligation for, but who are in the facility because of agreements the county has with another governmental entity to be paid for housing people in their custody, including:

- Individuals in state custody serving a sentence for a Class D (the lowest-level felony) or a Class C felony conviction;8

- Individuals being held for other counties; and

- Individuals being held for the federal government.

Kentucky currently has 70 “full service” county jails and 4 regional jails that incarcerate individuals for the county, the state, other counties and, in some cases, the federal government. There are also three “life safety” jails that do not meet the standards required to incarcerate individuals in state or federal custody.9

How Kentucky’s county jails came to be overcrowded

“Tough on crime” policies enacted in the 1970s and 1980s, including harsher penalties as part of the “War on Drugs,” significantly increased the number of people incarcerated in Kentucky and across the country. In the early 1980s, after the “War on Drugs” policies filled Kentucky’s state prisons, a class action lawsuit was filed by incarcerated people for abuse they suffered including conditions related to overcrowding, resulting in a federal court order restricting the number of people that could be incarcerated in several of the state prisons.10 But because the harsh policies were still in place, the number of people sentenced to serve felony sentences continued to grow. With limitations on capacity at the state prisons, the Kentucky Department of Corrections (DOC) administratively established a “controlled intake process” that resulted in incarcerated people awaiting transfer to a state facility remaining in county jails for an extended period of time, until a spot in a state prison opened up. Implementation of this policy resulted in further overcrowding in jails that for the most part were already over their capacity.

The state did not pay the counties at the time for holding people awaiting transfer, and the large influx of these individuals in DOC custody combined with the length of time they were staying created a significant strain on county budgets. In 1987, counties and incarcerated people filed a lawsuit seeking state reimbursement, as well as quicker transfer, because of the better conditions and programs offered in state prisons.11 Rather than mandating quicker transfers, the court required the state to pay counties for holding individuals in state custody. Importantly, the court also held that individuals convicted of a felony have a right to custody and care under the state constitution, but not necessarily in a state prison. This holding opened the door for a large share of incarcerated individuals in state custody to serve their sentences in county jails.

The impact of the court decision was that, rather than opposing the incarceration of individuals in state custody in county jails, counties reversed their prior position and sought to hold individuals in DOC custody because of the associated payments. As a result, the number of individuals in state custody held in county jails under the controlled intake process continued to grow.

In 1992, because Kentucky’s prisons remained full, legislation was passed requiring individuals serving sentences for Class D felonies (the lowest-level felony) of 5 years or less to do so in county jails, followed by legislation in 2000 “allowing” jails to hold individuals serving Class C and longer Class D sentences as well.12 Under the law, jails can refuse to house individuals in state custody, but in practice very few do — despite severely overcrowded conditions — because of the financial incentives. And in many cases, the overcrowding occurs not because of the number of people for whom the county is legally responsible, but because the county receives more income the more incarcerated individuals it holds. Housing people in state custody in local jails also cuts state costs in the short term, as the average cost paid to the jail per person is $35.43 per day (the per diem from the state is $31.34 but there are other costs, for example medical, for which county jails get reimbursed). That is far less than the daily cost to incarcerate someone in a state facility, which in 2021 ranged from $83.85 at the Bell County Forestry Camp, to $237.79 at Southeast State Correctional Complex, with an average cost across all state facilities of $97.60.13

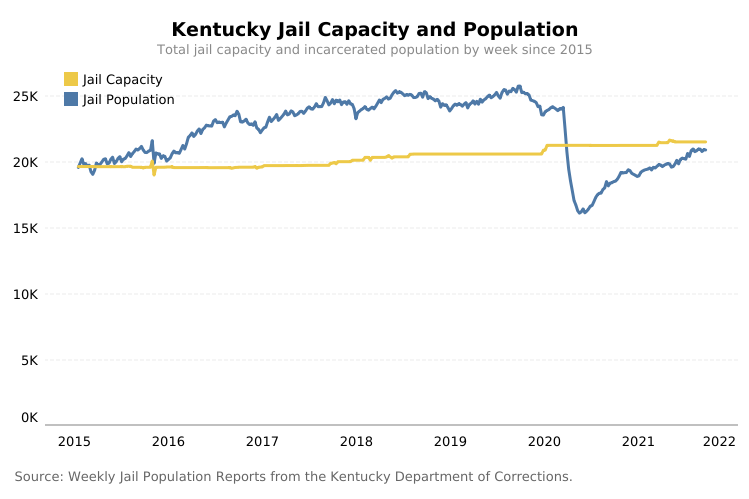

Kentucky county jails’ long history of extreme overcrowding was somewhat improved during the pandemic as many incarcerated people were released under a series of commutations and an administrative order to expand pretrial release, both to protect people from COVID-19.14 However, this progress has been steadily undermined, and today, dozens of the state’s county jails are again over capacity and overcrowded.15

Absent state-level policy change, counties have limited options to address the fiscal strains associated with county incarceration. The continued influx of incarcerated people and severe overcrowding have led many counties to build bigger facilities, often disproportionately large given the size of the county, in order to generate money by housing more incarcerated individuals for the state, other counties and the federal government. And when these large facilities are built, they fill up quickly.

How the financial structure of incarceration in Kentucky’s county jails increases incarceration

County jails are but one piece of the financial puzzle that counties are responsible for, and making all of the pieces fit to balance budgets has become more difficult over time. All Kentucky counties are experiencing increased pension costs, and rural counties in coal-producing areas are also suffering from revenue losses due to diminishing coal production. In addition, as more people relocate from rural to urban areas of the state, the ability of rural counties to generate tax revenues from other sources has diminished. All of these conditions create additional fiscal pressure for counties above and beyond uniformly increasing jail costs. This is especially true in rural counties, where most of the overcrowding and jail population increases are occurring. The ability of counties to control jail expenses is limited, in part because of the disconnect between the people making the decisions about incarceration and the county officials responsible for paying the cost of those decisions. In these circumstances, one of the few options available to balance both the jail and county budget is to find additional revenue sources within the system, as discussed in more detail below.

Incarceration costs

The human costs of incarceration cannot be overstated, in both the short and long term, on the health, wellbeing and economic security of individuals, families and communities. The experience of incarceration increases the prevalence of chronic health conditions and decreases life expectancy.16 Incarceration is associated with increased risk for overdose death.17 And new research indicates there are reduced health outcomes for family members of incarcerated people as well.18 In addition, incarceration makes it difficult to access education and high-quality employment. Negative impacts are experienced by individuals who are incarcerated while awaiting trial, even for a short period, and for those with misdemeanor convictions as well as felonies.19

Incarceration is also expensive. According to an analysis by the Vera Institute of Justice, Kentucky counties spent a total of $402 million on jail expenses in Fiscal Year 2019, with a county average of $3.4 million or approximately 15% of the total budget and $90 per county resident.20 There is a significant variance in how much counties spend on jails as a proportion of the budget — from 3% to 72% of the total budget and from $5 to $1,113 per resident — with rural counties spending a greater share of their budgets and more per capita on jail costs than counties home to smaller cities, suburban counties or Louisville/Jefferson County. The most significant jail expenditures are personnel costs (59% of jail expenditures) followed by contracted services such as health care (20%).

As previously described, counties are required by law to pay for the incarceration of people who are detained pretrial (usually because these individuals cannot afford to pay bail) or sentenced to serve time on a misdemeanor by the district and circuit courts serving the county. Misdemeanors carry a 12-month sentence or less, and along with pretrial incarceration, the length of jail time can vary significantly and can stretch on for months or even longer. The associated costs vary from county to county, but on average, the daily cost of incarceration in Kentucky’s jails is $44.21 These costs are, in large part, driven by factors beyond the control of the county jailer and include the impact of local policing practices, state laws and budgetary allocations, and prosecutorial and judicial decisions that result in people being detained.

A particular philosophy of one judge or one prosecutor, and methods such as being “tough on crime” or setting high bail amounts, can have a dramatic impact on the number of people who end up in a county jail. The resulting increase in jail populations can occur rapidly, leaving counties no time to adapt and with few options to address increasing costs. In most cases, a judge ultimately determines whether an individual is released on recognizance (ROR) or other nonfinancial types of release (without having to put money down), or is subject to money bail (and if so, how much). These practices vary widely from county to county, and overall, the rates of release without financial conditions in Kentucky are low, which leads to many Kentuckians being incarcerated pretrial.22

Chronic state underfunding and delays in Kentucky’s courts, and inadequate numbers of public defenders in the system, also contribute to increased pretrial incarceration.23 The criminal legal system has been used to respond to complex social problems too often, and prosecutors have not used their discretion to decline prosecution often enough. All of these factors keep the system clogged with too many cases, necessitating more money from state and local governments.

For people incarcerated pretrial because they cannot afford bail, these delays mean they languish in jail for longer periods of time. In many cases, people spend so much time in jail before their trial that when the trial finally happens, the sentence is actually shorter than the length of time they were detained, and they are released with time served — all of which has been paid for by the county, rather than the state.24 Counties have long argued that they should be reimbursed by the state for incarcerated people who are ultimately released after trial for time served pretrial because the judicial legal process took so long. However, this would require additional appropriations at the state level that so far have not materialized. It would also create a new perverse incentive at the front end of the system, where counties would actually be financially rewarded for pretrial incarceration.

County budgets are impacted by increasing numbers of people being held pretrial, and at the same time the per diem paid for people in state custody had not increased for over 15 years until 2021, when a temporary $2 per day increase was included in the budget funded with American Rescue Plan Act money.25 During the same period of time, jail costs have increased significantly leaving counties to make up the difference.

County budgets are also significantly impacted by state laws that drive up incarceration. Although county officials tend to focus on the negative fiscal impact to county budgets when a felony offense is reduced to a misdemeanor, county costs have also been increased significantly by the criminalization of what are referred to as “quality of life” offenses such as public intoxication and disorderly conduct, which are misdemeanors.

Incarceration revenues

All 120 counties have an elected jailer, whether the county operates a jail or not.26 All counties are required by statute to receive at least $24,000 per year from the state for operating the local jail, or, if the county does not have a jail, the cost of housing people in other counties.27 Those county allocations have not changed since they were first established in the 1980s, and are a fraction of the actual cost.

In addition to being cost centers, jails in some counties have also become significant revenue generators — in some cases to partially offset the increased cost of operating the jail, and in a few cases, to reportedly completely pay for the operation of the jail.28

Using the county jail to generate revenues in Kentucky represents one of the few ways that county governments are able to offset the cost of fulfilling a legal obligation through charging others for services. The General Assembly has supported these practices by enacting legislation that directs revenues to jails including the following:

Incarcerating on behalf of other governmental agencies: Jails receive payments for voluntarily incarcerating individuals for whom they are not legally responsible. The majority of jail revenue (58%) is intergovernmental.29 Some counties receive up to 86% of their jail revenue to house people for the DOC, while others receive up to 60% of their jail revenue to house people for the federal government — typically in larger jails in smaller counties that were built in part for this purpose.

Jails that incarcerate individuals who are in the custody of the state DOC receive a per diem of $31.34. Until a $2 temporary increase recently was approved by the General Assembly to help jails address COVID-related expenses, the per diem amount has been the same since 2008. As previously noted, for most jails, this amount is less than the actual cost of incarceration, adding to the financial pressures of operating the jail — and encouraging overcrowding to use economies of scale to help balance out the costs.

During the height of the pandemic, there was a reduction in the number of people incarcerated for the state in large part due to the governor’s commutations in response to the pandemic, which had an impact on jail budgets — resulting in some jails requesting additional funding from county fiscal courts.30 In October 2020, a local newspaper article quoted the Pulaski County jailer as saying: “Right now everyone is competing for state inmates…We’ve daily tried to seek out state inmates from other facilities but the Department of Corrections still will not allow transfer of state inmates from facility to facility.”31

Jails can also charge a locally determined per diem to other counties to incarcerate individuals held pretrial or serving misdemeanor sentences.32 This happens when the holding county either lacks room to incarcerate people or lacks a jail altogether. Amounts that counties charge to other counties to incarcerate people in their custody vary, but can be more than the amount received from the DOC for housing individuals in state custody.

Jails can also enter into an agreement with the U.S. Marshals or ICE to incarcerate individuals in federal custody for a negotiated per diem amount that is substantially higher than the state per diem, making it especially attractive.33 On Sept. 30, 2021, there were 21 county jails holding people on behalf of the federal government. Of those 21 jails, 11 were above 100% capacity. The jails with the highest proportion of federal prisoners to the overall population were Grayson County at 72% (jail at 113% of capacity), Oldham County at 60% (77% of capacity,) Crittenden County at 58% (121% of capacity), Woodford County at 55% (124% of capacity), and Laurel County with 54% (85% of capacity).34

With the largest population of people in federal custody already, the Grayson County jail was recently expanded by 200 beds, with the expansion described as follows by the jailer: “…[I]t’s mainly for female inmates, we currently have roughly 50 inmates, so we’re going to add on about 150 more inmates, so hopefully it will either be federal or state inmates.”35

Overcrowding and expanding the jail to house more people: A big problem in county jails is that overcrowding is intentionally used to take advantage of economies of scale. This approach works from a financial perspective because the fixed costs of operating a jail do not increase proportionately as more people are incarcerated, so housing two or more people in space meant for one can provide significantly more income per square foot, which helps to relieve the budgetary pressures. But allowing jails to accept payment to incarcerate people for whom they are not legally responsible creates overcrowded, unsanitary and often inhumane conditions for all those incarcerated. These dangerous conditions existed prior to, but were made worse by, the COVID-19 pandemic.36

In response to severe and chronic overcrowding, some counties move to build a bigger jail, rather than refusing to accept people from the state or the federal government to alleviate the strain. A number of Kentucky’s county jails have expanded specifically so that they can bring in revenue by incarcerating more people for the DOC, other counties and the federal government, using the money received to pay down bonds issued to construct or expand the facility. Because the payments are needed to satisfy debt, counties that use this method to finance construction or expansion become dependent on the payments until the debt is satisfied. This practice ends up increasing incarceration, as well as the county’s financial reliance on incarceration as a revenue generator long-term, perpetuating the status quo regarding state criminal justice policies.37 Policy changes to reduce sentences — which would ultimately have positive impacts on individuals, families and communities (including from a public health perspective) — would undermine the county jails’ bottom line. Therefore, counties often lobby against such changes.

Other revenue-generating options for jails: Counties often save money by organizing incarcerated people into work crews, including to do landscaping of publicly owned land and digging graves when families can’t pay for a burial, as well as cooking and cleaning in the jail, which would otherwise have to be paid for by the county. In some cases, jails even profit directly from this labor, such as having a contract with the Energy and Environment Cabinet for litter abatement.38 There are incentives for incarcerated Kentuckians to participate in these work programs — including earning time off of their sentences, getting a break from an overcrowded cell and receiving meager financial compensation.39

Jails can also charge a range of fees to people who are incarcerated, including a booking fee once an arrested person arrives at the jail, and a daily room and board fee to individuals being held pretrial or serving a misdemeanor sentence. A recent, high-profile, ongoing court case has brought attention to this practice. A man who was incarcerated pretrial in Clark County due to an inability to afford bail ended up being charged with $4,000 in jail fees even after he was ultimately released without being convicted.40

Jail commissaries make revenue from selling food and other items including e-cigarettes, which brought in more than $1.3 million in 2018 to nearly two-third of the state’s jails (with the remaining third not providing information).41 While commissary funds must be spent to benefit the lives of those incarcerated in the jail in some way, benefits can also accrue to the jail. For instance, funds have been used to purchase trucks to run a work program and an X-ray machine used when booking individuals into the jail. Also, when someone has money deposited into their account, known as money being put “on the books,” a jail can automatically apply a certain percentage of the funds to debts from various fees (determined by the county’s fiscal court).

Jails also make money from incarcerated individuals’ phone calls and video visits, which especially gained attention during the COVID-19 pandemic due to in-person visitations being reduced or eliminated (although even prior to COVID, a number of jails had eliminated in-person visitation).42 A recent state report on jail communications services found that in fiscal year 2020, 75 county jails received commissions totaling $9.7 million, and 29 jails received a total of $1.39 million from technology grants (monetary assistance awarded to the jail but not linked to a percentage of sales).43 While the average county derives just 5% of jail revenues from fees and charges, that’s still more than $24 million a year extracted from some of the state’s poorest residents.44 Approximately 47% of this revenue is from the telephone commission.

A bill passed in the 2021 Kentucky General Assembly included an appropriation for fiscal years 2022 through 2024 for additional funds for local jails when an individual serving a state sentence leaves incarceration having completed a DOC-approved program or programs resulting in a sentencing credit.45 Jails can receive between $300 and $1,000 depending on the type of program and amount of credit earned. In addition, jails will receive an increased per diem of $2 or $10 per day for each person enrolled in such programs while in the facility with the amount dependent on the program. In the past, jailers have advocated for such a “performance-based funding” initiative to be permanent, which could further incentivize jails to expand their facilities to increase program offerings.

Jail expansion is actually a driver of overcrowding

In Kentucky’s current perverse financial structure for jails, it would appear to make sense for counties to expand. One jailer we spoke with said, “You can never go too big,” and others seemed to share the sentiment. In Madison County for example, when proposing an expansion in 2019, county officials argued that it would be less expensive down the road to build a much bigger jail that could bring in income from individuals in state and federal custody.46 But as stated in the Vera Institute report, Broken Ground, “The cycle of jail growth and overcrowding is not an inevitable feature of local criminal justice systems.”47

Building larger jails doesn’t address the root causes of the overcrowding. As noted in Broken Ground:48

Although jail expansion provides additional beds to house increasing numbers of people, including local residents who had previously been outboarded to other county jail facilities, it does not fundamentally address the policies and practices — such as those related to arrest, bail, or sentencing — that directly impact the number of people sent to jail and how long they stay.

Incarceration is often framed as a solution to public safety and public health issues, rather than itself a problem, and jail expansion is often held up as a pragmatic answer to growth in the number of people in jail. However, accommodating increased incarceration not only fails to address overcrowding and overreliance on incarceration to address challenges in communities; it can actually make things worse all around. As noted by Vera, “The choice to invest in the infrastructure of confinement can virtually guarantee increased levels of confinement.”49

A limit on the number of available jail beds can act as a built-in mechanism to keep jail populations in check, while jail expansion can actually drive incarceration by alleviating the pressure to make needed changes.50 According to the Vera report, “Once jail capacity expands in these places, inertia among key institutional players (law enforcement, prosecutors, judges, etc.) may bias the local justice system to simply use a now more readily available resource: jail beds.”51 System actors may “forgo the very policies and practices — such as early release policies or decreased police enforcement — that had been implemented to accommodate previous capacity limitations.”52 Between 1999 and 2005, a time of declining crime rates, 216 county jails were constructed in the U.S., and the median jail population rose 27% after construction was completed.53 In the past couple of years in Kentucky, the new Rowan, Knox and Laurel county jails have filled up quickly and stayed full even during the pandemic.

It is also financially risky to undertake jail expansion. In some cases, the costs of constructing and operating a bigger jail exceed projected income, and in rare cases, counties find it too costly to open and operate newly built jails, leaving them shuttered. And while jail populations have been on the rise, jail projections are quite unreliable; they don’t necessarily reflect rising crime and aren’t inevitably going up.54

Some justify jail expansion based on the need to provide more jail programming for people who are incarcerated, which could accelerate if the move toward “performance-based funding” for jails in Kentucky is made permanent. The jailers we spoke with were proud of the programs and services they offered — including reentry and recovery-related programs — especially given the scarcity of jail programming in Kentucky. However, the underlying problems of Substance Use Disorders (SUDs), mental health problems and poverty are best treated in the community rather than in jail.55 And the effectiveness of jail programming still depends on a jail’s ability to link people to quality services in the community post-incarceration. As explained in the Vera report: “Expanding jail-based treatment services through jail construction ignores this gap in service provision in the community, perpetuating a system that only focuses on late-stage intervention — after someone has landed in jail — as opposed to prevention, and provides potentially higher quality interventions to people once they become harder to serve.”56

County jails demonstrate tension between need to reduce incarceration and balance budgets

County fiscal courts and jailers must balance budgets, but with very few options to address overcrowding and increasing costs related to pretrial incarceration without the support of prosecutors and judges. And they benefit financially from a large and constant stream of individuals convicted of felonies in state custody. The following detailed look at five counties illustrates how common strategies to address these issues only exacerbate incarceration and overcrowding.

Boyle County: One Judge Drives Up Incarceration

The Boyle County jail serves as a prime example of the impact that decisions made by one judge compounded by an overburdened and underfunded judicial system can have on a county. The Boyle County Detention Center, located in central Kentucky with Danville as the county seat, was built in the 1990s. Boyle County holds incarcerated people for neighboring Mercer County (which does not have a jail) pursuant to an interlocal cost-sharing agreement. Over time, the Boyle County jail became significantly overcrowded, due in part to low rates of pretrial release in both Boyle and Mercer counties. At its peak in recent years, there were 381 individuals incarcerated, despite total capacity of 220 (173% capacity). The jail population declined some in recent years, in part due to a “rocket docket” program run by the County Attorney, which expedites some cases and provides a reduced charge if a person pleads guilty. The jail population declined even more during the initial weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, although it began going back up quickly in May 2020 and is nearly at what is considered to be full capacity. As of this report publication, there are general plans in the works to expand the facility to 370 beds.57

It is well documented that many of the overcrowding issues of the Boyle County Detention Center (which pre-date COVID) are driven by low rates of pretrial release in both Boyle and Mercer counties — among the lowest in the state. In 2018, just 14% of cases in Boyle County resulted in release on nonfinancial conditions, and in Mercer County it was 17%.58 In previous years, these rates were even lower.

The Boyle County Fiscal Court commissioned an in-depth study to understand the drivers of jail overcrowding.59 It determined that the jail would not be overcrowded if changes were made to the county’s pretrial practices, including a circuit court judge’s “apparent refusal to set nonfinancial bonds” and his practice of revoking initial bonds set in district court and significantly increasing the bond amount, resulting in an arrest warrant being issued for those who had been released pretrial.60 This circuit court judge consistently sets the bond on the lowest-level felonies (Class D) at $5,000 cash, and $10,000 cash bonds are set on Class C. In some jurisdictions outside of Kentucky, similar bond schedules based on the offense alone and not taking particular circumstances into account (including ability to pay) have been found unconstitutional.

Because Boyle County circuit court arraignments are only held once a month, if the defendant is arrested due to the revocation of their initial bond after the last Thursday of the month, they will have to wait another month for arraignment, at which time the bond amount can be reconsidered. And the judge only holds one “plea day” (when a defendant can take a plea deal) per month, with a cap of 25 cases in the morning and 25 in the afternoon; if the number of defendants exceeds 50, the defendant has to wait another month. Heavy caseloads have resulted in a two-month wait to plead guilty — and if probation is a possibility the defendant has to wait yet another month for a presentencing investigation. According to the commissioned study, “An estimated 80% of felony defendants who receive a one-year sentence will be granted ‘time served’ at the point of sentencing. This is the result of having been detained for the amount of time they would have served a one-year sentence.”61 In 2017, 63% of felony defendants from Boyle and 68% from Mercer were detained during the entire pretrial period.62

Rates of pretrial release due to pleading guilty are unsurprisingly — but unfortunately — high in Boyle County, and the jail study concluded, “If the Circuit Judge had set more nonfinancial bonds the percentages…would have been much lower.”63 The report also notes: “Not shown…are the annual numbers of innocent defendants who pled guilty to avoid extended stays in jail. Interviews of attorneys in Boyle County support this contention — that some poor defendants plead guilty just to get out of jail and, thereby, avoid the long duration of case processing.”64

The study also identified that a lack of treatment facilities for addiction and mental health needs in the community was a key driver of jail overcrowding, as, according to police, they don’t have any alternatives except to take individuals to jail.65

Even though the Boyle County Detention Center would be close to capacity incarcerating only people being held pretrial or serving misdemeanor sentences, in part to offset the considerable financial costs of pretrial incarceration, the Boyle County jail brings in revenue for incarcerating individuals in DOC custody. As of Sept. 16, 2021, approximately 51% of the facility’s total population is in DOC custody (with 49% in Boyle or Mercer county custody presumably), which is a little higher than where it was prior to COVID.66

The Boyle County jail also generates some revenue by charging incarcerated individuals for various services. For example, the jail charges a $25 booking fee and $31 per day for room and board as of fall 2019 for individuals in county custody (these fees are set by the county fiscal court).67 When a person incarcerated in the Boyle County jail gets money deposited into their account, 25% of the deposit is automatically applied toward these accumulated debts before it can be used for phone calls and to purchase items through the commissary (until 2020 it was 50%).68 In fall 2019, the jailer estimated that $2.2 million was owed to the jail by formerly incarcerated individuals for these fees, debts that can be barriers to success post-incarceration.

The Boyle County jail is reportedly in poor physical condition and in need of significant renovations to the point that some have argued that it is better to build a much larger new jail instead of making repairs. However, the latest plan is to renovate the current structure while adding capacity for an additional 150 beds.69 This proposed solution does nothing to address the larger systemic issues, but provides more space to accommodate the proclivities of the Circuit Judge and to generate revenue to offset the associated financial costs.

Madison County: Pretrial Crowding from Drug Charges Leading County to Eye Expensive New Jail

The chronically overcrowded Madison County Detention Center is another example of the harms that result from local pretrial practices.70 Madison County’s overcrowding issues have received considerable media attention including coverage related to extremely poor living conditions.71 The jail, which was built in 1989, has a capacity of 184 beds and consistently operates over 150% capacity. Prior to COVID it was consistently around 200% of capacity.72

Like Boyle County, Madison County has relatively low rates of pretrial release; just 30% of cases resulted in release without financial conditions in 2018, and of those subject to money bail, 42% are able to afford release.73 The most common, most serious charge for individuals detained while awaiting trial in Madison County is drug possession, according to a snapshot study based on incarceration on Nov. 1, 2018.74 The Jan. 30, 2020 jail snapshot showed that the majority of individuals incarcerated in the Madison County jail were being held pretrial with no “corrections holders” that would make them ineligible for release.75 Few individuals incarcerated in the Madison County jail are in DOC custody because they simply do not have the space. Those in county custody are charged a one-time $50 booking fee and a $2 daily fee; 50% of money put on an individual’s books goes toward debts accrued from these and other fees.76

Madison County’s pretrial practices have driven up jail overcrowding in recent years. County officials view this crowding as putting them at risk of lawsuits, as well as costing significant money to necessarily house some individuals in other counties’ jails where they pay a per diem and the cost of transporting people to and from court dates. The county’s proposed solution in fall 2019 was to build a new jail more than four times the size of the current jail, with a cost of $45 million. The plan included additional capacity to bring in money from the state for holding individuals convicted of Class D and C felonies as well as from housing individuals in federal custody. The jail expansion, which was to be funded by a local property tax increase, was approved by the fiscal court, but a successful petition to have the tax increase put on the ballot for voter approval led the fiscal court to withdraw the project. Because the fiscal court and jailer cannot directly address overcrowding by releasing people from jail, the County Judge Executive testified before a state legislative committee in 2019 advocating for policy changes, including bail reform, to provide “relief” to the county.77

Leslie County: Jail as Revenue Generator in Face of Coal Decline

The Leslie County Detention Center, located in Hyden in the eastern part of the state, is just over a decade old and has a total capacity of 141 beds. However, it is perpetually and extremely overcrowded, and the overcrowding has increased over time. In 2015, the jail was at an average of 143% of capacity each week, and by 2019 it was at an average of 201% of capacity.78 While still overcrowded, the jail population was somewhat lower over the last year due to COVID-related releases, which a local news report framed in terms of its economic impacts: the resulting loss of income of $140,000 a month for the jail, requiring the jailer to lay off employees and take other cost-cutting measures.79 As of Sept. 30, 2021, the jail is at 160% of capacity.80

Unlike the Madison and Boyle county jails — where overcrowding is caused primarily by judges’ pretrial practices — Leslie County is overcrowded because of financial decisions made by the jailer and the fiscal court to accept payment to incarcerate people they are not legally responsible for.81 The Leslie County jail relies on being intentionally overcrowded, primarily holding individuals in state custody and from other counties for which payment is received. On the day of a site visit in October 2019, of 310 incarcerated individuals, just 47 or 16% were being held for Leslie County, with the remainder either in state custody or being held for another county.

A Vera Institute report has placed such practices in some eastern Kentucky counties in the context of decreasing revenue from the coal severance tax with the decline in coal production.82 Eastern Kentucky lost 73% of its coal jobs between 2011 and 2018, resulting in significant declines in median incomes in these counties. The Vera authors note: “At the same time that coal revenues dried up, the state’s criminal justice policies subsidized and incentivized the expansion of carceral capacity at the county level. Between 2011 and 2018, the number of people held in local jails in Kentucky under state jurisdiction increased 39 percent. During this same period, the number of people held for the counties continued to increase.”

In contrast to the other case study counties, the Leslie County jail doesn’t charge room and board fees to individuals in county custody given that, according to the jailer, most individuals just don’t have the money to pay the fees. Instead, the commissary is an important source of funds for the jail, although commissary funds can only be used for things that directly benefit the people incarcerated in the jail. While some counties only offer the commissary a couple days a week, the Leslie County jail chooses to offer the commissary every day.83 And the funds raised go toward running the jail’s extensive work programs (landscaping, grave-digging, cleaning out the animal shelter on a regular basis, etc.) by paying for work trucks and other needed items. In October of 2019, the jailer estimated approximately 100 incarcerated individuals in the jail were doing some kind of work.84

Leslie County is reportedly considering adding on to its current jail facility.

Barren County: Financial Incentives Resulting in Crowding Despite Better Pretrial Practices

In contrast to Boyle and Madison Counties, Barren County in the western part of the state is notable for its high rates of pretrial release — with 64% of cases resulting in release without financial conditions, the 3rd-highest rate in the state in 2018.85 But the jail is still crowded because the county chooses to take people from other counties and charge significant fees as well as house those in state custody. That results in the jail (built in 2011 to replace a building that was built in the 1970s) breaking even or even bringing money to the county through revenues generated there at the time of our visit in October 2019.86 Even during the initial pandemic surge, the jail was at 124% capacity as of Dec. 17, 2020, and up to 133% of capacity on Sept. 16, 2021.87

There are many similarities between Barren County and Leslie County in terms of the large share of people incarcerated in their jails for other governments. In 2019, more than a third of people incarcerated in the Barren County jail were in state custody and a large share were held for other counties, primarily Metcalfe and Monroe, which do not have their own jails.88 In the fall of 2019, the jail charged $40 per day to incarcerate individuals for other counties. According to the jailer, in 2019 the jail population typically consisted of 20-30 individuals housed for Metcalfe County, 20-30 for Monroe and 80-100 for Barren. The remaining approximately 110-150 individuals were held for the state. The jail has a total capacity of 178 beds, which it clearly exceeds.

In the Barren County jail, in fall 2019, the booking fee was $55, room and board was $40 per day and 50% of money put on the books for people who are incarcerated was diverted to satisfy these accruing debts.

Rowan County: Major Jail Expansion Brings More Income, Not Relief from Overcrowding

Rowan County built a new jail in 2018, in part because of overcrowding at the old facility, but ultimately because it was renting the building from Morehead State University and the arrangement was no longer tenable. Although the county considered building a new jail equal to the size of the building it was leaving behind which had 78 beds (total capacity), it instead built a new jail at 3.5 times the capacity with 275 beds.89

Prior to the jail’s expansion the jail was at a weekly average of 159% capacity in 2017. Demonstrating how building bigger is only a stop-gap solution to the bigger problem of policies leading to mass incarceration and overcrowding, in less than a year after the July 2018 opening, the new jail exceeded the higher capacity, averaging 111% of capacity weekly in 2019.90 Even with COVID-19, the jail was nearing 100% of capacity at the end of 2020 and was at 116% of capacity as of Sept. 16, 2021.91

While Rowan County has a relatively high rate of pretrial release on nonfinancial conditions, it opted to build bigger than was necessary in order to bring in income by holding people for the state and other counties.92 In fall 2019, the jail charged $35 a day to incarcerate individuals for Morgan and Elliott counties, which don’t have their own jails. As of 2019, the Rowan County jail’s booking fee was $50, room and board was $25 a day, and 25% of money put on the books went toward these fees. During our visit in 2019, the county treasurer praised that for the first time, the county didn’t have to pay any of the jail’s bills other than the bond payment. The cost of building the jail was $20.7 million.93

Two more eastern Kentucky counties — Knox and Laurel — have opened expanded facilities to incarcerate more people in DOC custody in the past year or so, and in the case of Laurel to incarcerate individuals in federal custody as well. Both counties (and Knox especially) are small communities that have invested in disproportionately large jails. In Knox County, with a population of just over 30,000 people, there is a relatively new 294-bed jail. Laurel County (population 61,000) now has 915 jail beds, with more than half of incarcerated individuals held there in federal custody.94

Policy Recommendations

Overcrowding and jail expansion exacerbate, rather than resolve, the many harms related to incarceration, including on county budgets. The list below is a non-exhaustive set of policy ideas that would move the state forward on these issues, resulting in fewer people incarcerated in both the short and long term. Some of these policies — such as pretrial reforms — would immediately benefit counties financially, while others — such as cannabis legalization — are expected to have a minimal impact on county budgets given the relatively small number of people who actually end up incarcerated for cannabis possession, though would still be beneficial over time. Given the perverse incentives and financial tensions described in this report, the changes described below necessarily work together to move the commonwealth forward in reducing incarceration while at the same time addressing county fiscal constraints and the resulting pressures opposing meaningful change.

Make needed changes to the state’s pretrial system

Kentucky has a disparate pretrial system that unduly punishes people with lower incomes. The experience of Kentucky and other states with expansion of the administrative release program in response to COVID-19 demonstrates that it is possible to release more people pretrial without compromising public safety. Making these changes permanent would both reduce the societal harms of incarceration and help to alleviate the fiscal strain counties are experiencing.

Absent the full elimination of money bail, Kentucky should limit the number of offenses for which money bond can be set, and guarantee people charged with crimes more robust due process. Such reforms would prohibit money bail from being used to detain individuals due to a lack of financial resources. Another reform that would help to address harms and provide fiscal relief to counties is a fast and speedy trial provision such as what Senator Brandon Storm proposed in Senate Bill 223 in the 2021 General Assembly.95 As noted previously, cases in Kentucky’s court system can drag on for months and sometimes years, resulting in people who cannot afford bail being detained for long periods of time.

Enact meaningful sentencing policy changes

Some felony charges, such as drug possession and possession of a forged instrument, among others, should be reduced to misdemeanors, building on the changes the state legislature passed in the 2021 session related to theft and being behind in child support payments (“flagrant nonsupport”).96 This would reduce the number of Kentuckians in state custody, both pretrial and after sentencing, who are incarcerated and later face the damaging collateral consequences of a felony conviction in terms of access to employment, housing, education and more. And while sentencing reform could increase the number of individuals in county custody serving misdemeanor sentences whose incarceration must be paid for by the county, if taken together with other reforms that reduce county costs described in this section, these measures could be a net benefit for county jails, and clearly for the communities in which they operate. In addition, sentencing for misdemeanors doesn’t have to involve incarceration and can be a non-custodial sentence or diversion; these are choices available to prosecutors and judges.

Other misdemeanor offenses should be decriminalized or reduced to prepayable violations, which would mean fewer court proceedings, no arrest or jail expenses and no supervision costs for counties, among other benefits. The Department of Public Advocacy recommends the following as possible misdemeanor offenses to be reduced to violations: controlled substance not in proper container, possession of drug paraphernalia, unlawful access in the third and fourth degree, criminal trespass in the second and third degree, criminal possession of a noxious substance, criminal littering, unlawful assembly, disorderly conduct in the second degree, public intoxication and unlawful transaction with a minor in the second degree (truancy), among others.97

Given the ineffectiveness of increasing criminal penalties for drug-related offenses in decreasing overdose deaths or the prevalence of SUDs, the state specifically needs to enact policy changes that impact individuals with underlying SUDs — such as legalizing cannabis and making simple drug possession a misdemeanor rather than a felony.

Kentucky should also eliminate, or at least severely limit, its “Persistent Felony Offender” (PFO) law, which is among the broadest and most severe mandatory minimum laws in the country.98 While these long sentences are not served in county jails, by more broadly reducing incarceration in the state, it takes pressure off the system that has created the perverse incentives for the state to support the practice of housing individuals serving Class C and D sentences in county jails. Parole eligibility, which is limited for individuals serving PFO sentences as well as sentences for what are considered to be violent offenses, should also be expanded (absent full elimination of PFO).

Invest more in community-based treatment and alternatives to incarceration

The most appropriate setting for SUD treatment is in the community. If counties spend less on incarceration, additional resources can be made available for needed investments in community services. And while incarcerated individuals do not qualify for Medicaid (medical care is largely covered by the county and/or the state, with jails often charging fees as co-pays for some medical services), if individuals receive services in the community, rather than in jail, they are Medicaid eligible. There should be more diversion efforts that provide access to care and resources before arrest. In terms of diversion post-arrest, clinicians need to be integrated into the decision about connecting people to community-based care before booking or at booking (when people are still Medicaid eligible).

Statewide and local efforts should be made to connect individuals in need of services pretrial to supports in the community. The Kentucky General Assembly heard testimony in 2020 about several counties in other states that have successfully provided these services pretrial for individuals with mental health needs and co-occurring SUDs — including Bexar County, Texas and Johnson County, Iowa — in part as a response to jail overcrowding.99

It is important that the state avoid “performance-based funding” for jails or other policies that expand programming in jails, and to instead use these resources to provide them in the community.100

Stop wave of jail expansion

In order to permanently reduce our state’s high rates of incarceration, counties must stop expanding their jails. As described in the Vera Institute report Broken Ground, new jail beds are often inevitably filled.101 While expanding jails may seem like common sense for county budgets, it causes more problems than it solves, and it makes it difficult for the state to move forward with much-needed reforms that are occurring successfully in other states. It is also an expensive financial risk to counties. Kentucky’s response to the pandemic has shown that incarceration, and jail overcrowding, can be successfully reduced.102

The legislature should develop a comprehensive plan to phase out the use of local jails completely for people in state custody over a set number of years, in partnership with local governments and the DOC, in a manner that helps to identify and address local fiscal issues and concerns through the transition period.

Work together locally to make needed changes in multiple systems to reduce incarceration

As prior recommendations indicate, there are many changes needed at the state level to address the punitive nature of our criminal system, and to reduce the harms to families and communities caused by the system. But there are also actions that can and should be taken locally at the same time, especially in communities faced with jail overcrowding and increasing jail costs. Rather than building bigger jails, county governments can and should do research to better understand where and how decisions about incarcerating people are made, and the impact of those decisions, like Boyle County did. The state should provide financial support for this research.

Counties can also facilitate community conversations that include law enforcement, prosecutors, judges, defense attorneys, incarcerated people and other community members to better understand the impacts of the current criminal system, how the community is both hurt and helped, and what changes can be made locally to address the issues, beyond building bigger jails or holding more people for payment.

- Prison Policy Initiative, “Kentucky Profile,” https://www.prisonpolicy.org/profiles/KY.html. According to the most recent (2019) data from the U.S. Department of Justice, Kentucky is tied for the 5th-highest rate of incarceration in jails and prisons per-capita. U.S. Department of Justice, “Correctional Populations in the United States 2019 – Statistical Tables,” Bureau of Justice Statistics, July 2021, https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/cpus19st.pdf.

- Ashley Spalding, “Kentucky Has Much to Learn from Other States on Criminal Justice Reform,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy,” Jan. 30, 2019, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-has-much-to-learn-from-other-states-on-criminal-justice-reform/.

- In its goals for the 2021 legislative session, the Kentucky Association of Counties (KACo) listed as one of its top priorities “jail relief,” noting that: from 2011 to 2019, the total population in Kentucky grew by about 2%, and that over the same period, county jail populations grew by more than 30%, having a significant impact on county budgets. Almost half of county officials in the KACo poll said that jail costs are the biggest pressure on their budgets.” Kentucky Association of Counties, “Jail Relief,” KACo Priority, https://www.kaco.org/legislative-services/current-session/jail-relief/.

- It is worth noting that these conditions occur despite state regulations for physical conditions and space in jails. Physical Plant, 501 KAR 3:050, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/kar/501/003/050.pdf. While jails voluntarily hold many of these individuals in state and federal custody, there is also a “controlled intake” population of people that jails are statutorily required to hold who have been sentenced and are waiting to be transferred to a state prison. Jails are paid a per diem for holding these people.

- At the same time, pretrial detention can have a downstream impact on both felony and misdemeanor sentences given that being incarcerated while awaiting trial makes a person more likely to plead guilty or be found guilty if the case goes to trial. Ashley Spalding, “Disparate Justice: Where Kentuckians Live Determines Whether They Stay in Jail Because They Can’t Afford Cash Bail,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, June 11, 2019, https://kypolicy.org/disparate-justice-where-kentuckians-live-determines-whether-they-stay-in-jail/”

- John Cheves, “Caged,” Herald-Leader, Aug. 21, 2019, https://www.kentucky.com/news/local/watchdog/article231443768.html

- Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Prisoners in 2019,” October 2020, https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/p19.pdf. Department of Corrections “Weekly Jail Population Reports,” https://corrections.ky.gov/About/researchandstats/Pages/WeeklyJail.aspx. For context, states with the highest number of state prison populations housed in county jails other than Kentucky and Louisiana include Mississippi, Utah, Tennessee and Virginia, which all house approximately a quarter of their state prison populations in jail.

- Individuals convicted of felony sex crimes cannot serve their sentences in county jails. Place of imprisonment, 532.100 KRS, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=50895.

- Department of Corrections, “Weekly Jail,” https://corrections.ky.gov/About/researchandstats/Pages/WeeklyJail.aspx. The Lewis County and Lincoln County jails have closed in recent months.

- Kendrick v. Bland, 541 F. Supp. 21 (W.D. Ky. 1981), https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/541/21/2288628/.

- “Campbell County v. Commonwealth,” 762 S.W.2d 6 (1988), https://cite.case.law/sw2d/762/6/.

- Robert G. Lawson, “Turning Jails into Prisons — Collateral Damage from Kentucky’s War on Crime,” University of Kentucky, 2006, https://uknowledge.uky.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1139&context=law_facpub.

- Kentucky Department of Corrections, “Cost to Incarcerate – FY21,” https://corrections.ky.gov/About/researchandstats/Documents/Annual%20Reports/Cost%20to%20Incarcerate%202021.pdf.

- Ashley Spalding, “New Data Helps Pave the Way for Bail Reform in Kentucky,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 21, 2021, https://kypolicy.org/new-data-helps-pave-way-for-bail-reform-in-kentucky/. Crime and Justice Institute, “How Criminal Justice Systems Are Responding to COVID-19,” https://www.cjinstitute.org/corona/.

- Cheves, “Caged.” Carmen Mitchell and Dustin Pugel, “Despite Continued Risks from COVID-19, Kentucky Jail Population Continues to Increase,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Feb. 4, 2021, https://kypolicy.org/despite-covid-19-risks-kentucky-jail-population-continues-to-increase/. As noted by Kentucky legal scholar Robert Lawson, “Professionals say that penal facilities are full when eighty-five percent of the beds are occupied, an observation that at least provides perspective on the overcrowding that exists in Kentucky jails … Without a doubt, overcrowding is a truly overwhelming problem from one end of the jail system to the other, an unmanageable condition that affects every aspect of life inside jail living areas.” Lawson, “Turning Jails into Prisons.”

- J. Acker, P. Braveman, E. Arkin, L. Leviton, J. Parsons and G. Hobor, “Mass Incarceration Threatens Health Equity in America,” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Dec. 1, 2018, https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2019/01/mass-incarceration-threatens-health-equity-in-america.html.

- Elias Nosrati, Jacob Kang-Brown, Michael Ash, Martin McKee, Michael Marmot and Lawrence P. King, “Economic Decline, Incarceration, and Mortality From Drug Use Disorders in the USA Between 1983 and 2014: An Observational Analysis,” Lancet Public Health (2019), pp. 326-333, https://perma.cc/75LT-TARA.

- Emily Widra, “New Data: People with Incarcerated Loved Ones Have Shorter Life Expectancies and Poorer Health,” Prison Policy Initiative, July 12, 2021, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2021/07/12/family-incarceration/.

- Terry-Ann Craigie, Ames Grawert and Cameron Kimble, “Conviction, Imprisonment, and Lost Earnings: How Involvement with the Criminal Justice System Deepens Inequality,” Brennan Center for Justice, Sept. 15, 2020, https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/EconomicImpactReport_pdf.pdf. Léon Digard and Elizabeth Swavola, “Justice Denied: The Harmful and Lasting Effects of Pretrial Detention,” Vera Institute of Justice, April 2019, https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/Justice-Denied-Evidence-Brief.pdf.

- Jasmine Heiss, Beatrice Hallbach-Singand Chris Mai, “The Cost of Jails in Kentucky,” Vera Institute presentation to the Interim Joint Committee on Judiciary, July 8, 2021, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/8/13370/Jul%2008%202021%20KY%20Jail%20Costs%20Vera%20Inst.pdf.

- Vera Institute, “What Jails Cost – Kentucky,” https://www.vera.org/publications/what-jails-cost-statewide/kentucky.

- Ashley Spalding, “Disparate Justice.”

- Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, “What Does Kentucky Value,” January 2020, https://kypolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Final-online-draft.pdf.

- Public Advocate Damon Preston and Deputy Public Advocate Scott West, personal communication.

- HB556 21RS, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/21RS/documents/0194.pdf. The increased amount was intended to be retroactive for one year, and to apply for the 2021-22 budget year, but the jails didn’t actually receive the retroactive payments because of limitations on the use of ARPA money retroactively.

- Kentucky is the only state that has a publicly elected jailer; in most states, the sheriff is responsible for the local jail.

- Kentucky Revised Statutes 441.206, “State Contribution for Jail – Allocation – Payments to be made Annually – Use of Funds,” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=39615.

- Alyssa Williams, “The Laurel Co. Correctional Center Is One of the Only Self-Sufficient Facilities to Date,” WYMT, July 22, 2021, https://www.wymt.com/2021/07/22/laurel-co-correctional-center-is-one-only-self-sufficient-facilities-date/. Matt Lasley, “Jail Cuts Ribbon on New Expansion,” The Grayson County News-Gazette, March 27, 2021, https://www.messenger-inquirer.com/grayson_county/news/jail-cuts-ribbon-on-new-expansion/article_813e8681-6d6a-5fce-9ec0-7c68f23d3c3d.html.

- Heiss, Hallbach-Singh and Mai, “The Cost of Jails in Kentucky.”

- Don Sergent, “COVID Takes Bite Out of Jail Budget,” Bowling Green Daily News, March 26, 2021, https://www.bgdailynews.com/news/covid-takes-bite-out-of-jail-budget/article_90a37b49-5afa-5729-9276-0c685d24a61e.html.

- Janie Slaven, “Jail Budget Estimate Holding as County Waits for More State Inmates,” Commonwealth Journal, Oct. 8, 2020, https://www.somerset-kentucky.com/news/local_news/jail-budget-estimate-holding-as-county-waits-for-more-state-inmates/article_525f4fd6-e45f-5f92-9da9-4b9c856162d6.html.

- By law, the amount cannot be more than three times the state per-diem, or more than the actual cost to incarcerate. Transfer of Prisoners to Secure Jail, KRS 441.520, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=49957.

- Katie Pickens, “Jail to See Additional Revenue with Increased Per Diem Rate for Federal Inmates,” The Owensboro Times, May 27, 2020, https://www.owensborotimes.com/news/2020/05/jail-to-see-additional-revenue-with-increased-per-diem-rate-for-federal-inmates/.

- Department of Corrections, Weekly Jail Population Report, Sept. 30, 2021, https://corrections.ky.gov/About/researchandstats/Documents/Weekly%20Jail/2021/09-30-21.pdf. Note that some jails operate multiple facilities and that figures reported relate only to facilities operated by jails where people in federal custody are held.

- Anna Medina, “Grayson County Detention Center Expansion Project Successfully Complete,” Channel 13 WBKO, March 29, 2021, https://www.wbko.com/2021/03/30/grayson-county-detention-center-expansion-project-successfully-complete/. Lasley, “Jail Cuts Ribbon on New Expansion.”

- Cheves, “Caged.”

- Chris Mai, Mikelina Belaineh, Ram Subramanian and Jacob Kang-Brown, “Broken Ground: Why America Keeps Building More Jails and What It Can Do Instead,” Vera Institute of Justice, November 2019, https://www.vera.org/publications/broken-ground-jail-construction.

- Sergent, “COVID Takes Bite Out of Jail Budget.” Slaven, “Jail Budget Estimate Holding as County Waits for More State Inmates.”

- Prison Policy Initiative, “State and Federal Prison Wage Policies and Sourcing Information,” https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/wage_policies.html.

- Ryland Barton, “Kentucky Supreme Court Hears Case Over Jail Fees,” WFPL, April 21, 2021, https://wfpl.org/kentucky-supreme-court-hears-case-over-jail-fees/.

- R.G. Dunlop, “How These Jail Officials Profit From Selling E-Cigarettes to Inmates,” Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting and ProPublica, Jan. 29, 2020, https://www.propublica.org/article/how-these-jail-officials-profit-from-selling-e-cigarettes-to-inmates.

- Kentucky Revised Statutes 441.265, “Required Reimbursement by Prisoner of Costs of Confinement – Local Policy of Fee and Expense Rates – Billing and Collection Methods,” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=19341. Kentucky Revised Statutes 534.045, “Assessment of Reimbursement Fee Against Jail Prisoners – Collection – Fee Determination – Relevant Evidence – Modification,” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=20099.

- Mike Harmon, Auditor of Public Accounts, “Data Bulletin: An Examination of County Jail Communication Services and Equipment Contracts,” July 15, 2021, http://apps.auditor.ky.gov/Public/Audit_Reports/Archive/2021JailCommServicesDataBulletin.pdf.

- Heiss, Hallbach-Singh and Mai, “The Cost of Jails in Kentucky.”

- Ashley Spalding, Carmen Mitchell and Pam Thomas, “The 2021 Legislative Session Criminal Justice Wrap Up,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, April 16, 2021, https://kypolicy.org/2021-legislative-session-criminal-justice-wrap-up/.

- A newspaper article described Laurel County’s decision to expand its jail, which opened in January 2020, in the following way: “[Jailer] Mosley said the new center will house between 200 to 250 federal prisoners, which will generate revenues to offset the construction and operational costs of the new facility. ‘With 200 to 250 federal inmates, that will generate around $8 million a year,’ Mosley explained. ‘That has been my goal from the beginning – to make this jail self-sufficient and at no costs to the taxpayers.’” Nita Johnson, “New Laurel County Jail Opens Next Week,” The Sentinel Echo, Jan. 10, 2020, https://www.sentinel-echo.com/news/local_news/new-laurel-county-jail-opens-next-week/article_29619dd2-d136-5674-857a-f400f94bd607.html.

- Mai et al., “Broken Ground.”

- Mai et al., “Broken Ground.”

- Mai et al., “Broken Ground.”

- Mai et al., “Broken Ground.”

- Mai et al., “Broken Ground.”

- Mai et al., “Broken Ground.”

- Mai et al., “Broken Ground.”

- Mai et al., “Broken Ground.”

- Mai et al., “Broken Ground.” Carmen Mitchell, “Waiver to Provide Substance Use Disorder Treatment to Incarcerated People Shouldn’t Increase Incarceration,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Nov. 10, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/comments-re-medicaid-waiver-1115-sud-incarceration-services/.

- Mai et al., “Broken Ground.”

- Boyle County Fiscal Court Meeting, Nov. 10, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LFeozqpI2zA.

- Spalding, “Disparate Justice.”

- Brandstetter Carroll, Inc., “Boyle-Mercer County Detention Center Study,” November 2018, http://boyleky.com/boyle-mercer-county-detention-center-study/. Despite the first half of the report outlining specific ways the jail overcrowding issue could be addressed at the county level, the report concludes with a recommendation to rebuild the jail due to concerns about the physical state of the facility and provides several scenarios for expanding jail capacity at the same time. This is common in jail studies conducted by architectural firms. Mai et al., “Broken Ground.”

- This judge serves both Boyle and Mercer counties.

- Brandstetter Carroll, Inc., “Boyle-Mercer County Detention Center Study.”

- Brandstetter Carroll, Inc., “Boyle-Mercer County Detention Center Study.”

- Brandstetter Carroll, Inc., “Boyle-Mercer County Detention Center Study.”

- Brandstetter Carroll, Inc., “Boyle-Mercer County Detention Center Study.”

- Brandstetter Carroll, Inc., “Boyle-Mercer County Detention Center Study.”

- Vera Institute, “Kentucky Jail Population, January 2020 – September 2021,” https://public.tableau.com/profile/in.our.backyards#!/vizhome/KentuckyJailDashboard/Summary?publish=yes.

- The cost of video visits was $9.90 for 30 minutes as of fall 2019 when we visited the jail. A Vera analysis shows 30% of revenue from jail fees and charges in Boyle County ($71,413) in 2019 was from the telephone commission. Vera Institute of Justice, “What Jails Cost – Kentucky,” https://www.vera.org/publications/what-jails-cost-statewide/kentucky.

- Ben Kleppinger, “Who Should Pay for Jail? Boyle Reducing Fee on Families Sending Money to Inmates,” The Advocate-Messenger, Feb. 14, 2020, https://www.amnews.com/2020/02/14/boyle-planning-to-reduce-fee-levied-on-families-sending-money-to-inmates/.

- Boyle County Fiscal Court Meeting, Nov. 10, 2020.

- Unlike other counties, we did not speak directly with the Madison County jailer or tour the jail facility; however, we attended community meetings and spoke with several local officials and actors related to the jail expansion. This location was added to our analysis after the pre-COVID jail visits to the other four counties were conducted in fall 2019.

- Cheves, “Caged.”

- Department of Corrections, weekly jail population reports, https://corrections.ky.gov/About/researchandstats/Pages/WeeklyJail.aspx.

- Spalding, “Disparate Justice.”

- Ashley Spalding, “Newly Available Data Shows Madison County Jail Crowding Driven by Low and Moderate Risk Defendants Awaiting Trial for Low Level Offences,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Sept. 9, 2019, https://kypolicy.org/newly-available-data-shows-madison-county-jail-crowding-driven-by-low-and-moderate-risk-defendants-awaiting-trial-for-low-level-offenses/.

- Corrections holders include federal detainers, probation/parole detainers, serving a state or county sentence and civil holds. May, “Kentucky Pretrial Population: One Day Snapshot Findings.”

- Madison County Detention Center, “Inmate Services,” http://www.madisoncountydetention.com/Inmate_Services.html. Personal communication, Madison County Detention Center staff.

- Ashley Spalding, “Building a Huge, Expensive Jail Would Be a Big Mistake for Madison County,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Sept. 6, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/op-ed-building-a-huge-expensive-jail-would-be-a-big-mistake-for-madison-county/. Susan Riddell, “KACo Presents 2020 Legislative Priorities,” Kentucky Association of Counties, Nov. 22, 2019, https://onthefloor.kaco.org/stories/kaco-presents-2020-legislative-priorities/.

- KyPolicy calculations. At the time of our visit in October 2019, there were 40 women in a 20-person pod, with women sleeping on the floor. The jailer noted that in order for the state to allow the facility to take in more individuals for the state, given how overcrowded the jail is, they have to make sure the maintenance of the building is kept up (i.e., when there are plumbing problems they are addressed quickly).

- Will Puckett, “Jails Feeling Pinch as Budgets Take Hit From COVID-19,” WYMT, May 13, 2020, https://www.wymt.com/content/news/Jails-feeling-pinch-as-budgets-take-hit-from-COVID19-570445891.html.

- Department of Corrections, Weekly Jail Population Report, Sept. 30, 2021, https://corrections.ky.gov/About/researchandstats/Documents/Weekly%20Jail/2021/09-30-21.pdf.

- Leslie County actually has low rates of pretrial release on nonfinancial conditions, but it doesn’t cause a big financial strain because of the vast majority of individuals housed in the county jail being held for the state or other counties (in other words, bringing in revenue). Spalding, “Disparate Justice.”

- Jack Norton and Judah Schept, “Keeping the Lights On: Incarcerating the Bluegrass State,” Vera Institute, March 4, 2019, https://www.vera.org/in-our-backyards-stories/keeping-the-lights-on.

- According to the jailer, there was $600,000 in the commissary account in October 2019. Personal communication.

- Most receive $0.65 a day, and for every 40 hours of work their sentence is reduced by a day.

- Spalding, “Disparate Justice.”

- However, it should be noted that the jailer asserted he does not view this as what the purpose of a jail should be.

- Vera Institute, “Kentucky Jail Population, January 2020 – September 2021.”

- Metcalfe County and Barren County have the same judges.

- Correctional News, “Rowan County to Build New Jail,” Oct. 7, 2015, https://correctionalnews.com/2015/10/07/rowan-county-build-new-jail/.

- KyPolicy analysis of DOC data.

- Vera Institute, “Kentucky Jail Population, January 2020 – September 2021.”

- The rate of pretrial release on nonfinancial conditions in 2018 was 55% of cases. Spalding, “Disparate Justice.”

- Brad Stacy, “New Jail Ribbon Cutting, Tours Are Friday,” The Morehead News, July 18, 2018.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Vera Institute, “Kentucky Jail Population, January 2020 – September 2021.”

- SB223 21RS, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/21rs/sb223.html.

- Spalding, Mitchell and Thomas, “The 2021 Legislative Session Criminal Justice Wrap Up.”

- Kentucky Department of Public Advocacy, “Over Incarceration,” https://dpa.ky.gov/News-and-Public-Information/issuesinpublicdefense/Pages/Over-Incarceration.aspx.

- Kentucky Department of Public Advocacy, “Over Incarceration.”

- Jasmine Heiss, Testimony to the House Budget Review Subcommittee on Justice, Public Safety and Judiciary, Feb. 11, 2020.

- Carmen Mitchell, “Waiver to Provide Substance Use Disorder Treatment to Incarcerated People Shouldn’t Increase Incarceration.”

- Mai et al., “Broken Ground.”

- Recent concerns over individuals released through the governor’s commutations committing new crimes exaggerate what the data shows, which is that the rates of recidivism for these individuals are comparable to recidivism rates more generally for people leaving prison or jail. There are significant barriers to successful reentry that should be better mitigated through policies like automatically providing photo IDs upon release, among many others. Carmen Mitchell, “IDs Are a Necessity for Successful Reentry,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Oct. 1, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/ids-are-a-necessity-for-successful-reentry/.