Thanks to federal pandemic aid that helped keep Kentucky residents and businesses afloat, the state ended 2021 with a substantial revenue surplus, and currently expects another large surplus in the summer of 2022. That offers a tremendous opportunity to help Kentucky families who continue to struggle in the pandemic, begin reversing years of budget cuts, and create the conditions for a strong and sustained economic recovery that benefits everyone.

Note: A PDF version of this report is available here.

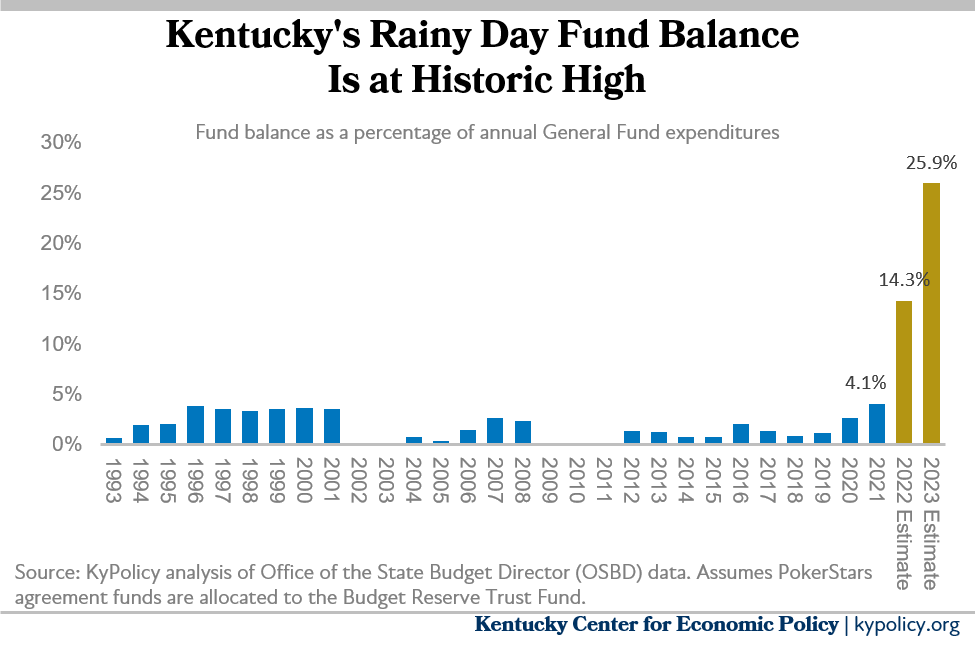

Current projections are for the surpluses to increase the balance in the state’s Budget Reserve Trust Fund (BRTF) – also known as the rainy day fund – in July 2022 to $3.2 billion, or 25.9% of the state’s General Fund budget. As described in this brief, a reserve of this level is not necessary at this time given the state’s immediate needs, the purpose of a rainy day fund, and what experts and experience tell us about responsible fund amounts. Kentucky’s leaders should set the BRTF at 5% of the state’s budget in the next two-year budget – which would be larger than its balance at any point between 1993 and 2021 – and use the rest of the surplus to reinvest in public services and a robust recovery from the pandemic.

This approach would free up over $2 billion over the next several years that can provide relief to Kentuckians still struggling and allow critical reinvestments in schools, health, human services and other vital needs depleted by over a decade of budget cuts. At the same time, the General Assembly should avoid giving away the surplus in tax cuts that would benefit corporations and wealthy individuals and other poor uses that would take away from the opportunity to make historic investments in Kentuckians.

Kentucky’s leaders also should use this moment to reform the BRTF to make it a more reliable fiscal tool going forward. Under current rules, the BRTF has been kept too small, and policymakers have been able to use it for non-emergency needs, resulting in a very small reserve as the state entered the pandemic. The General Assembly should amend the BRTF law to require building the reserve to a reasonable level over a period of years, and to prevent the fund from being used outside of emergency needs.

There is a tremendous need to invest in Kentucky’s families and economy right now

Although Kentucky has a budget surplus, the state has by no means recovered from the pandemic. Many Kentucky residents continue to struggle from the effects of the pandemic, and the damage may last for years. Kentucky’s decision makers must take into account the enormous challenges we still face to achieving full recovery from the COVID-19 recession. That is why the best approach to using the recent surplus is to invest it back in Kentucky families and public services.

As of August, the state still had 76,000 fewer jobs than before the pandemic hit in February 2020. While the unemployment rate was only 4.3% in August, there were 92,000 fewer Kentuckians in the labor force than before the pandemic who were not counted in that figure, which means the real unemployment rate was approximately twice that high.1

The Delta variant threw a new wrench into the recovery process, including by keeping people out of the labor market as they deal with illness and care responsibilities. The Federal Reserve does not expect the U.S. unemployment rate to return to pre-pandemic levels until 2023.2 The length and pain of the recession depends substantially on the willingness of states and the federal government to spend dollars to help stimulate recovery.

With a still weak economy, needs for families and communities continue to be extraordinary, and the state surplus can be a tool for providing relief. More than 1 in 4 Kentucky adults still report “difficulty covering usual household expenses” according to Census data; 21% of renters are behind on rent payments; and 9% of Kentucky parents say children in their household are not eating enough because they cannot afford it.3 The end of the eviction moratorium, the expiration of expanded unemployment benefits, the upcoming resumption of student loan payments and the expiration of other support programs are increasing hardship even as the economy is still weak and the pandemic is far from over.

There were also increases in drug overdose deaths and mental health challenges during the pandemic that need public investment and services to help address. It is clear that people in Kentucky are still hurting, and that significant investments are needed to help all Kentuckians move forward.

In addition, Kentucky’s ability to create a robust recovery and address future challenges is limited due to the harms from 19 rounds of budget cuts since 2008. Kentucky is somewhat unusual among states in its failure to begin to restore cuts made during and after the Great Recession through reinvestment prior to COVID. The General Assembly passed another austere budget in 2021.4

Core functions of government are severely depleted, which left us unprepared to respond to the challenges of COVID. There is chronic underinvestment in areas ranging from child welfare to college affordability, community-based services for people with disabilities, mental health and substance use disorder treatment, school-based services, child and elder care, and more. Prior to COVID, the state was already having difficulty delivering essential services in some areas because of outdated technology and high employee turnover due to low wages and compensation in many parts of government, with state employees not receiving raises for 9 of the last 11 years.5

Kentucky’s historically large surplus is thanks to federal aid that kept the state afloat

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in enormous damage to the U.S. economy, and forecasters predicted similar harm to state tax revenues. However, in Kentucky, state General Fund revenues actually grew by 1.5% in fiscal year 2020 and then by 10.9% in 2021.6 The surprising result stemmed from the unprecedented federal aid passed by Congress through the CARES Act, American Rescue Plan Act and other relief packages.

This aid was essential to offsetting the steep economic decline and to keeping residents and businesses from falling into deeper hardship. For example, net earnings from work in Kentucky fell by $9 billion due to massive layoffs in the second quarter of 2020 when COVID-19 first hit. Despite that huge decline, total personal income in the state actually rose by $21 billion because transfer payments from the federal government increased by $31 billion.7 The federal response to COVID-19 was much more substantial and in proportion to the need than the response to the Great Recession, which was widely understood to be inadequate relative to the size of the downturn, resulting in sluggish economic recovery for most of the 2010s.8

Federal COVID aid boosted household incomes directly and kept businesses open. Aid included stimulus checks, expanded unemployment benefits, increased food aid, assistance to state and local governments, Paycheck Protection Program grants to businesses and much more. This aid increased sales and income tax receipts as Kentuckians spent these dollars in the economy and as financial markets bounced back. In other words, the state’s surplus is largely due to the actions of the federal government.9

The commonwealth ended the 2021 fiscal year in July with a surplus of $1.1 billion, which was deposited in the rainy day fund. Along with money already in the BRTF and a deposit of $154.9 million scheduled for this year, the balance increased to $1.92 billion. Since then, the legislature appropriated $411 million from the BRTF through Senate Bill 5 passed in the September 2021 special session to provide subsidies for large industrial projects.10 In addition, the state announced a final agreement with online gambling site PokerStars following over a decade of litigation, bringing in $225 million that goes to the General Fund surplus account, which makes it eligible to be deposited in the BRTF. The addition of this $225 million to the $1.5 billion in the BRTF would result in a balance of $1.7 billion or 14.3% of Kentucky’s General Fund.

The state’s Consensus Forecasting Group is projecting another surplus of $1.5 billion next summer as of its preliminary estimate established at its October meeting. If that surplus materializes, it would bring the state’s potential balance to $3.2 billion or 25.9% of the General Fund, as shown in the graph below.

Kentucky has not managed its rainy day fund well

The purpose of a rainy day fund is to help finance public services during economic downturns or other external shocks, when state revenues typically decline or grow more slowly.11 Kentucky’s constitution, like that of almost every other state, requires a balanced budget even during recessions. States tap rainy day funds to help fill budget gaps when revenues sag or new costs arise due to unforeseen circumstances.

Rainy day funds play a critical economic role. Using a rainy day fund during bad economic times is good for the economy. Doing so injects spending that then circulates through communities, creating jobs, supporting businesses and helping recovery get off the ground. Conversely, when rainy day funds are inadequate and states must cut their budgets during recessions, it makes downturns worse by further reducing spending in the economy. That exacerbates job and income loss and can make recessions longer and more painful. Credit rating agencies support using rainy day funds during downturns, and building them up during good times.12

Tapping rainy day funds when the economy is weak also helps people and communities at their time of greatest need with supports like health coverage, assistance with food and household expenses, mental health and substance use disorder services, monies for people to go to college or training when jobs dry up, and much more. As the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities notes, states “should not start rebuilding reserves until they have adequately addressed the hardships people are facing.”13

Despite this critical role, Kentucky has not managed its rainy day fund well. Contributions during good times have been insufficient, and the state has drawn money from the fund when the economy was strong and when the balance was still small.

Going back to 1993, Kentucky’s BRTF never reached even the legislatively established modest goal of 5% of General Fund expenditures, and between 2002 and 2020 it never exceeded 3% of expenditures. As discussed below, state fiscal experts recommend building up reserves during good times to 15% of the state’s budget. That means Kentucky entered both the pandemic and the Great Recession in 2008 with woefully inadequate rainy day reserves.

Meanwhile, state decision makers have drawn dollars from the rainy day fund for purposes not related to an economic or natural disaster emergency. Between 2014 and 2018, the state withdrew over $160 million from the BRTF during times the economy was relatively strong even though the fund balance at the time was in all cases less than 2%.

The poor use of Kentucky’s rainy day fund reflects in part limitations in the statute that established it, which provides minimal direction and guidance. It requires an automatic deposit of surplus General Fund revenues at the end of each fiscal year into the BRTF until the fund balance reaches 5% of General Fund receipts.14 But that goal is inadequate, and the statute does not establish a process or standards for when and how the BRTF should be replenished absent a General Fund surplus, or describe conditions in which the BRTF should be used. Further, the General Assembly regularly suspends that statute and directs the General Fund surplus for other uses. That results in a situation where deposits to the BRTF are irregular, and until 2020, were insufficient to provide the kind of reserves necessary to weather an economic downturn without having to significantly cut expenditures.

How big should Kentucky’s rainy day fund be today?

Kentucky’s rainy day fund is clearly flawed and has not prepared the state well for economic downturns. As the state emerges from the pandemic, and as decision makers consider what to do with the surplus, it is an important time to consider reforms to rainy day fund law, and to consider how big the rainy day fund should be at the current moment.

Determining what is an appropriate amount to hold in a rainy day fund is multifaceted. One way of understanding what is needed is to “stress test” the state’s budget based on past experience. There are several factors that are important to consider when estimating how much the state might need in its fund to prepare for the next downturn:

- The expected frequency of recessions or downturns;

- The expected depth of recessions or downturns and the impact on revenues;

- The expected willingness of the General Assembly to raise revenue during recessions or downturns to help fill the resulting budget gap;

- The state budgetary costs that go up during recessions or downturns;15

- The expected extent of federal aid during a recession or downturn, and how that will impact the need to draw down the rainy day fund.

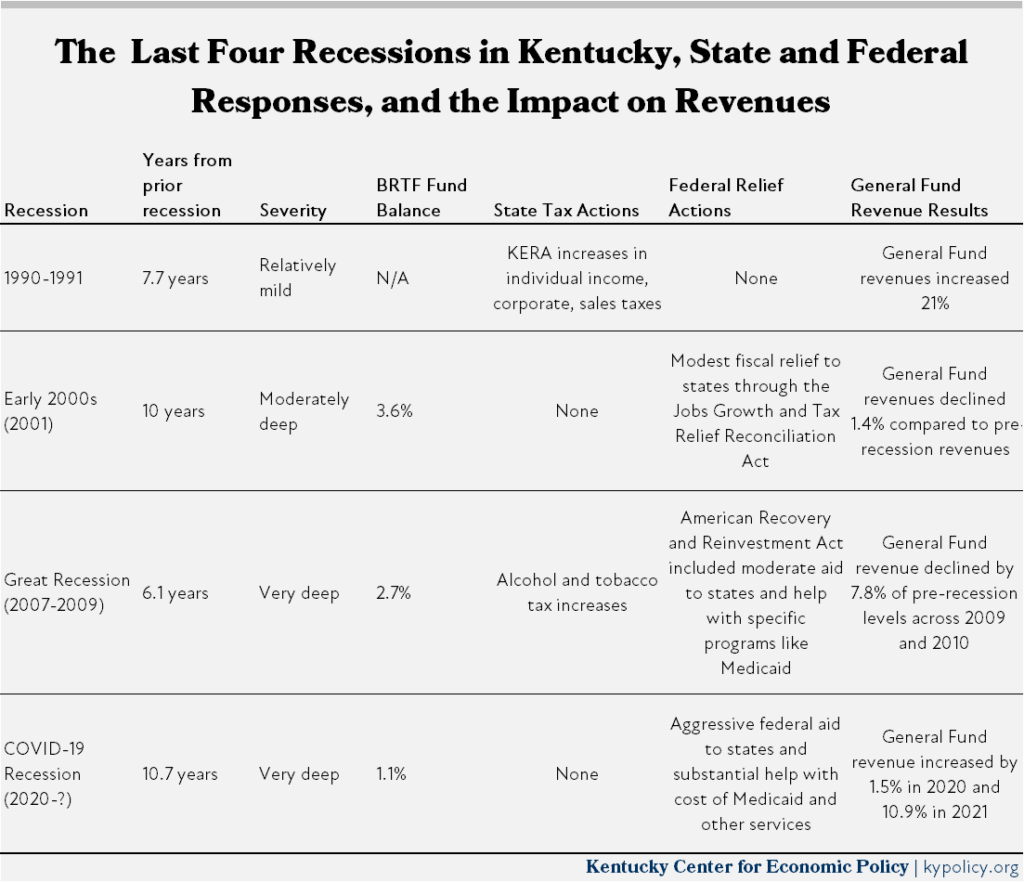

There is no way to predict these factors with certainty or precision. We can, however, look at recent history and use that experience to inform planning for the future. The most recent four recessions in Kentucky looked as follows:

Kentucky’s challenges managing the budget during recessions have varied significantly. The state should have had a much bigger rainy day fund balance in place before the Great Recession, which Kentucky entered with a balance equal to only 2.7% of General Fund expenditures.16 In other instances, the milder nature of the recession, aggressive federal aid and/or state willingness to raise revenue have lessened the need to tap the BRTF, as shown in the table above.

In recent years, many states have increased the targets for their rainy day funds, in part due to the increased severity of the last two recessions related to the growing volatility of the global economy. Some experts suggest 15% of the state General Fund as a more adequate goal. Connecticut, Georgia, Michigan, Oklahoma and Virginia raised their goal to 15% following the Great Recession.17

It is important to note that whatever the target for a fully funded rainy day reserve, Kentucky and other states should expect reserve balances to rise and fall over time as they are used and replenished. Rainy day balances should dip during economic crises and national disasters and then should be built up as state economies recover. Given that most economic recoveries last several years, it is reasonable to build up rainy day funds over a number of years in preparation for the next downturn.

As discussed below, we recommend reforming the BRTF to set a goal of 15% of the General Fund. This target does not need to be met immediately, especially given that the economy is still so fragile, but instead can be built up over a period of years.

Recommendations

Kentucky should use a substantial portion of its surplus to provide relief and seed budget reinvestment over the next few years

Given that we are not yet out of the current recession, a rainy day fund balance of 26% of the budget, as currently projected for FY 2023, is excessive. It is imperative that Kentucky reinvest a portion of its surplus into restoring recent budget cuts and providing relief and stimulus to help get out of the COVID-19 recession. The state can do so while also setting aside a portion to begin rebuilding the BRTF and while making structural changes to the fund that will result in more adequate contributions in the future.

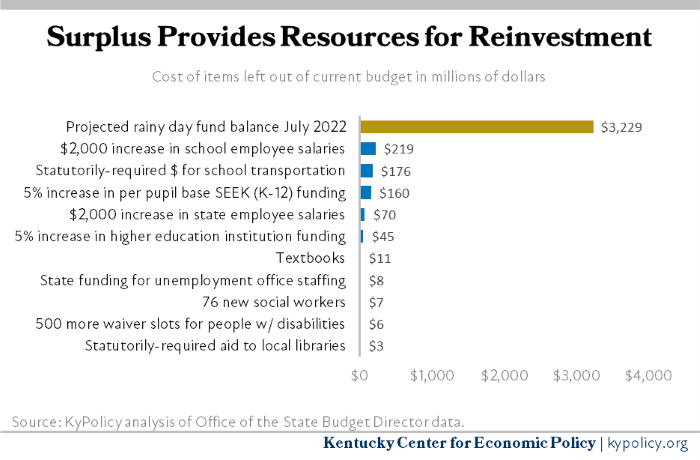

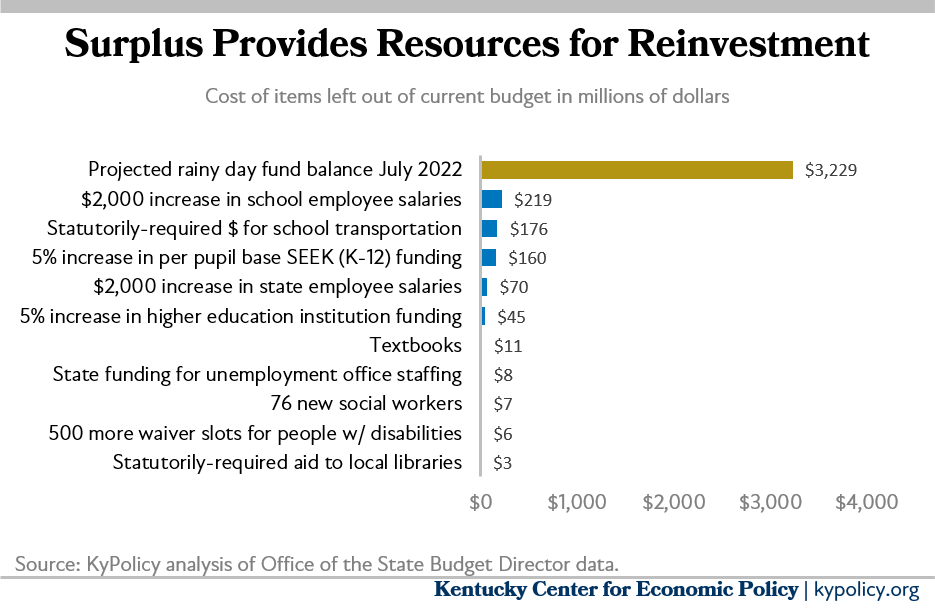

As illustrated in the graph below, the costs of a sample of needs left out of the current budget are modest compared to the expected size of the rainy day fund. We could do these things and more and still leave a healthy rainy day fund.

A BRTF balance of 5% of the General Fund at this time would make sense because the state should prioritize spending to address widespread economic pain and to support a strong recovery. An adequate rainy day fund is needed in time for the next recession, but not at all periods in between. With an average of 8.6 years between recessions over the last few decades, it is reasonable to expect that there will be a number of years to build the fund further before it will be needed again.

Setting a rainy day fund equal to 5% of the General Fund for FY 2022 and FY 2023 reflects a balanced approach. First, it would be more than the state has had in fund in any of the previous 29 years. Second, the state could develop a plan to build its reserves over the next several years to reach the 15 percent target. Third, this approach would give Kentucky access to more than $2 billion to spend over the next 2-4 years to begin reinvesting in essential services and programs and to provide immediate relief to people and communities.18

Tax cuts and other poor uses of the surplus should be rejected

The state must be careful not to give away the surplus on tax cuts and giveaways for corporations and wealthy interests. There is no evidence supporting claims that broad tax cuts attract businesses and individuals and grow economies, but ample evidence that they take resources away from investments in schools, health, infrastructure and more that do work.19 In fact, states that moved away from income taxes in recent years have grown no faster economically than other states.20 Tax cuts for special interests are also typically permanent and come off the top before a single dollar goes to the budget, impairing our ability to sustain public investments in the future that benefit everyone.

The state should not use any of the surplus to build more jails or prisons, or on other policies that further increase Kentucky’s damaging levels of mass incarceration. Experience across states show that “if you build it, they will fill it,” meaning that constructing more of these facilities will just create a new and bigger crowding problem in the future. Mass incarceration has harmful impacts on individuals, families and communities. Kentucky needs criminal justice reforms to reduce incarceration, and investments in alternative public services like housing and health to improve community well-being

Additionally, some are noting the size of Kentucky’s pension liabilities when discussing ways to use the surplus. But Kentucky has dramatically increased contributions to its pension plans in recent years and is now contributing on an annual basis using the most conservative assumptions in the country for the state employees’ plan (including investment return assumptions that are more conservative than the plans are actually delivering). These are resulting in growing fund balances. Also, reinvesting in the budget, including by providing raises to employees and hiring for positions previously cut, is one of the best actions we can take to improve the long-term health of the pension plans. It will increase payroll and bring new members into the systems whose contributions will bolster the plans.

The state should improve how it structures its rainy day fund to increase savings in the future

The General Assembly should update the BRTF statute to replace the current 5% cap. It should set a more reasonable goal, such as achievement of a BRTF balance equal to 15% of the General Fund by 2 years prior to the end of the average time period between recessions. Given the history of the last 4 recessions described above and the proposed 5% starting point, that would mean increasing the balance of Kentucky’s rainy day fund from 5% to 15% over a period of 6.6 years, or an average additional contribution of approximately 1.5% of the budget per year. The law should set goals accordingly to achieve the 15% target over time, with a requirement that when year-end surpluses do not achieve those goals by themselves, additional contributions to the BRTF be made in the budget in years where revenue growth is significantly higher than average.21

In addition, the General Assembly should amend the BRTF statute to limit its use to instances of an economic downturn or other external shock, and to include commonsense rules that are not overly complicated or onerous allowing the BRTF to be accessed. The state could also require regular stress tests of the BRTF to inform legislative decision-making, with the results of these tests reported to the Appropriations and Revenue Committee.

Kentucky will also need additional sustainable state revenues to keep moving forward

Utilizing a portion of the existing budget surplus now as seed dollars for reinvestments in schools, health, human services and more will help to ensure a robust recovery. But making these investments now is only the beginning. Kentucky will need to generate additional state revenues that will sustain over time to continue these investments in the future – a need that has long been understood. There are dozens of tax policy options the state could enact in order to close loopholes and ask those at the top to better chip in and create a tax system that grows with the state’s economy.22

- KyPolicy analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

- Federal Reserve Board and Federal Open Market Committee, “Summary of Economic Projections,” September 22, 2021, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20210922b.htm.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Tracking the COVID-19 Economy’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships,” September 10, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-economys-effects-on-food-housing-and.

- Jason Bailey, “Legislature to Pass Austere Budget, Prevent Governor from Using New Federal Aid Without Authorization,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, March 13, 2021, https://kypolicy.org/legislature-to-pass-austere-budget-prevent-governor-from-using-new-federal-aid-without-authorization/. Office of the State Budget Director, “2020-2022 Governor’s Recommended Budget,” February 4, 2020, https://osbd.ky.gov/Publications/Documents/Presentations/20-22%20Budget%20Presentation%20to%20House%20and%20Senate%20A%20and%20R%20-%202-4-20%20-%20FINAL.pdf. Dustin Pugel, et al., “Defeating the Pandemic and Building a Robust Recovery: A Preview of the Budget of the Commonwealth,” December 14, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/defeating-the-pandemic-and-building-a-robust-recovery-a-preview-of-the-budget-of-the-commonwealth/.

- Pugel, “Defeating the Pandemic.” Bailey, “Legislature to Pass.”

- Office of the State Budget Director, 4th Quarter Fiscal Year 2021 Economic and Revenue Report, https://osbd.ky.gov/Publications/Quarterly%20Economic%20and%20Revenue%20Reports%20%20Fiscal%2017/21-4thQrtRevenue.pdf.

- Numbers are quarterly but annualized. Bureau of Economic Analysis, State Personal Income by Major Component.

- Josh Bivens, “Why is recovery taking so long—and who’s to blame?” Economic Policy Institute, August 11, 2016, https://www.epi.org/publication/why-is-recovery-taking-so-long-and-who-is-to-blame/.

- Not all states are in the same positive fiscal condition. Kentucky is among 20 states whose 2020 calendar year receipts grew compared to 2019, while the remainder of states experienced revenue declines. Major declines were seen in states dependent on oil revenue and on tourism, including Alaska, North Dakota, Hawaii, Oregon, Nevada, Texas and Florida. The existence of a diverse set of taxes in Kentucky including corporate and income taxes also helped the state achieve a surplus. Barb Rosewicz, et al., “States Close Out 2020 with Widespread Tax Revenue Gains, Pew, July 27, 2021, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2021/07/27/states-close-out-2020-with-widespread-tax-revenue-gains.

- Senate Bill 5, 2021 Special Session, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/21SS/documents/0003.pdf.

- Elizabeth C. McNichol and Ed Lazere, “States Should Improve the Design of Their Rainy Day Funds,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 3, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/states-should-improve-the-design-of-their-rainy-day-funds.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Rainy Day Funds and State Credit Ratings,” May 2017, https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2017/05/statesfiscalhealth_creditratingsreport.pdf.

- McNichol and Lazere, “States Should Improve.”

- KRS 48.705, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=22575.

- Recessions do not only harm revenue, they also put pressure on public spending. Additional costs typically include Medicaid (for which more people are automatically eligible), increased enrollment in higher education, larger pension contributions due to lower investment returns and increased spending to address rising social needs. However, as mentioned earlier, some of those increased costs may be offset with federal aid (or more than offset, in the case of the COVID response). For example, in the COVID recession the federal government both sent general direct aid to states and helped fund particular programs such as through a higher federal match for Medicaid expenditures and direct funding for schools and universities.

- Jason Bailey, “Lessons from the Great Recession: Kentucky and Other States Need More Federal Relief,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, April 29, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/lessons-from-the-great-recession-kentucky-and-other-states-need-more-federal-relief/.

- McNichol and Lazare, “States Should Improve.”

- Jason Bailey, “Historic Surplus Leaves State in Strong Place to Begin Reinvesting in Kentucky’s Needs,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, August 4, 2021, https://kypolicy.org/historic-surplus-leaves-ky-in-strong-place-to-invest-in-state-needs/.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Tax Cuts and State Economies,” https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/resource-lists/tax-cuts-and-state-economies.

- Michael Leachman and Michael Mazerov, “State Personal Income Tax Cuts: Still a Poor Strategy for Economic Growth,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 14, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-personal-income-tax-cuts-still-a-poor-strategy-for-economic.

- For example, Washington State has a rule that growth in general fund state revenues that exceed by one-third the average biennial percentage growth in general state revenues over the prior five fiscal biennia be deposited in the rainy day fund.

- Jason Bailey and Pam Thomas, “Revenue Options that Strengthen the Commonwealth,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, March 2, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/revenue-options-that-strengthen-the-commonwealth/. Jason Bailey, “Tax Plan Would Fix Kentucky’s Budget Challenges by Addressing Upside Down Tax Code,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, February 13, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/tax-plan-would-fix-kentuckys-budget-challenges-by-addressing-upside-down-tax-code/.