The COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing economic downturn reshaped Kentucky’s economy in ways that are still revealing themselves thirty months after the virus arrived in the commonwealth. Part of the story is good news for workers. Aggressive federal pandemic aid has stimulated a record fast recovery and a tight labor market that have begun to drive up wages, increase job opportunities and accelerate unionization efforts. This progress is much needed after years of eroding job quality and stagnant wages.

This report is available as a PDF here.

Despite these gains, hardworking Kentuckians still find it difficult to make ends meet and provide for their families. Job quality and opportunities lag behind for some workers, including women, Black Kentuckians, those in the public sector and rural residents. Rapidly rising prices are eating away at wage gains even while federal pandemic aid comes to an end. Rising interest rates are increasing the odds of a recession in the near future. And recent state policy decisions to roll back unemployment benefits and other attempts to make cuts to the safety net will only make it harder for families to get by when a recession eventually comes.

To support workers, their families and the economy as a whole, Kentucky should focus on policies that improve job quality and wages, address rising family costs by bringing down the price of childcare and other essentials, and reinvest in creating good public sector jobs that meet important community needs in rural and urban areas. These policy needs are not new, but the unique risks of the moment add to their urgency.

Kentucky’s recovery is rapid but uneven

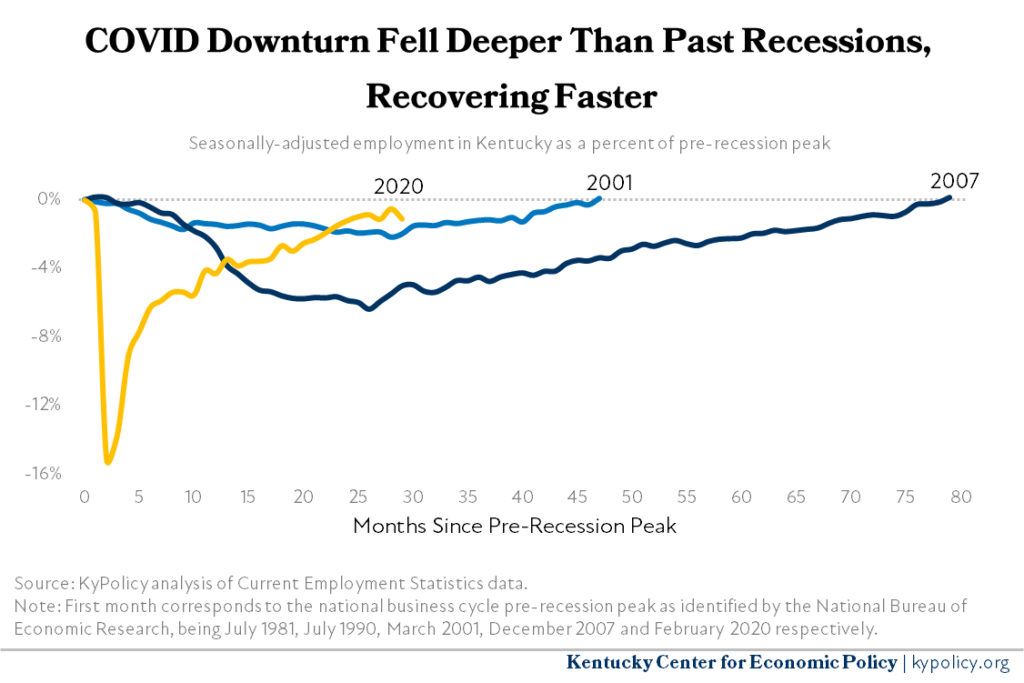

The early months of the COVID-19 pandemic took a significant toll on Kentucky’s economy, especially the labor force. Between March and April of 2020, Kentucky lost 294,900 — or more than 1 in 7 — jobs. That decline was deeper and faster than any previous downturn in Kentucky by a wide margin. Yet, the recovery has also been rapid by historical standards, with the state averaging 6,200 net new jobs a month since July 2020 and putting us on pace to return to pre-pandemic levels of employment much faster than the previous two downturns.1

This rapid recovery is thanks in large part to the four rounds of federal relief, which provided an array of financial assistance to nearly every Kentuckian beginning in March 2020.2 In addition to several programs that pre-dated the pandemic, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and state unemployment insurance, the four COVID-19 related packages provided direct checks, a boosted child tax credit, expanded unemployment benefits, state and local aid, and other programs that kept hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians out of poverty and, by stimulating the economy, brought jobs back.3 In doing so, consumer spending remained high, returning to pre-pandemic levels by January 2021, and has been much higher than pre-pandemic spending levels since.4 For example, in 2020 when unemployment insurance claimants were receiving an additional $600 weekly benefit, it was estimated that the increased spending supported roughly 49,750 jobs.5 There is evidence that these benefits were well targeted toward alleviating hardship and increasing consumer spending while having minimal effect on people’s choices about returning to work.6

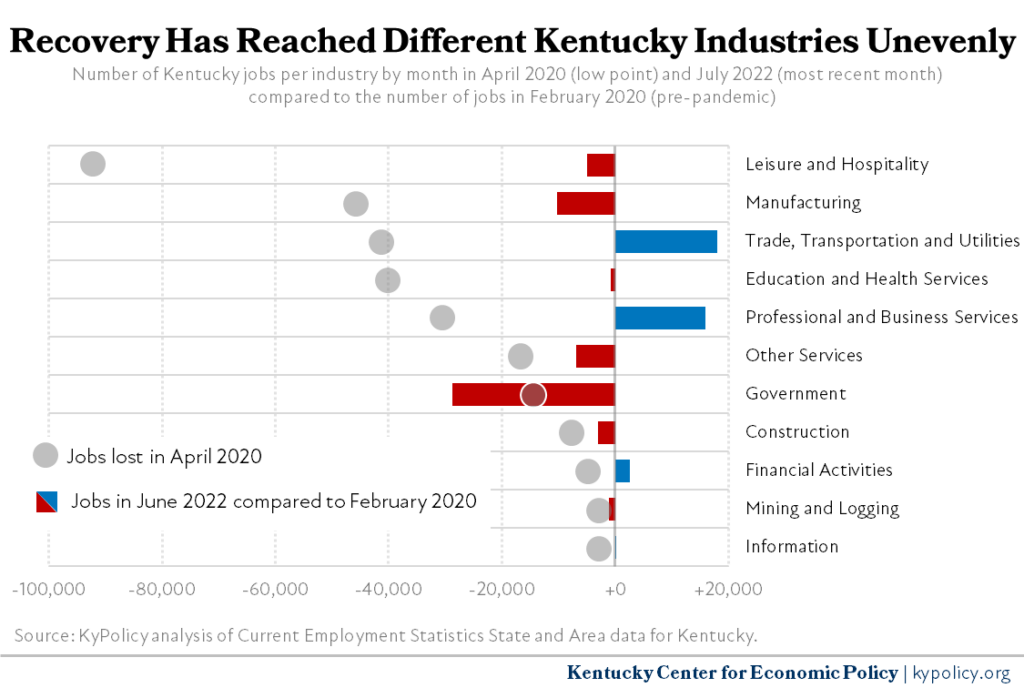

While the jobs recovery has been robust overall, it hasn’t been so across the board. For example, industries including Trade, Transportation and Utilities (a category in which warehousing jobs have particularly grown) and Professional and Business Services (which has seen a bump in temp agency employment and other administrative support) are now well above pre-pandemic levels of employment, and the Financial Activities category (such as banking, insurance, real estate, etc.) is now slightly above. But other industries, such as Leisure and Hospitality, Manufacturing, and Other Services (which includes everything from machinery repair to nonprofit organizations) have yet to fully recover.

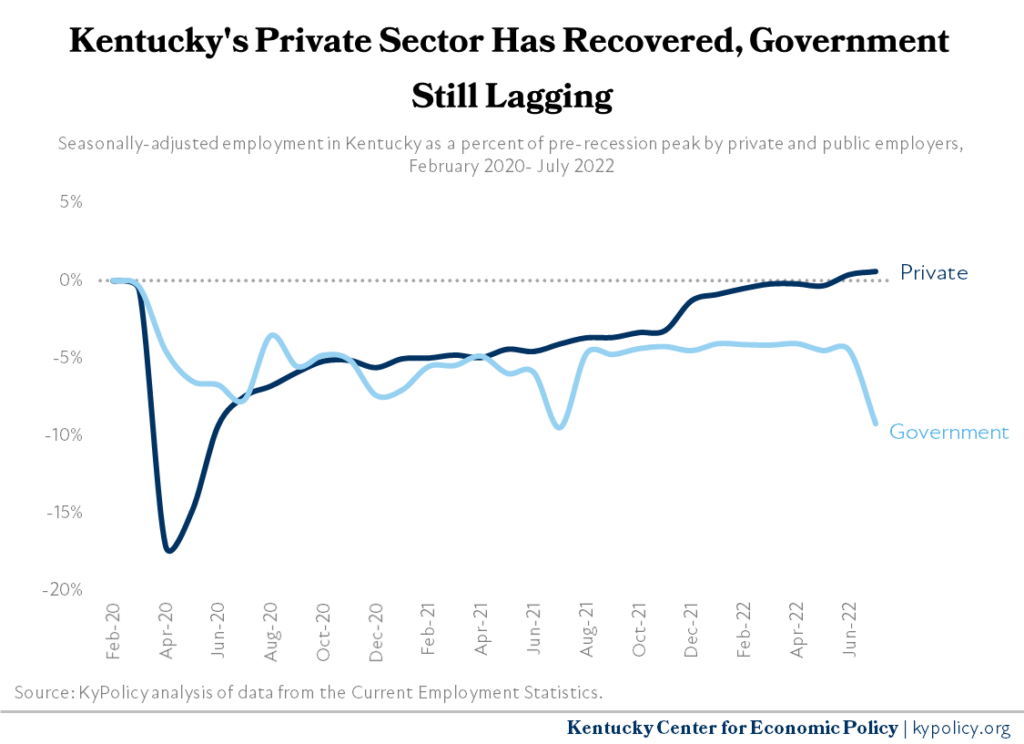

Government employment, specifically in state and local government, has actually worsened since the overall employment trough of April 2020, and it’s the only sector to have done so. In fact, job growth has been so robust in the private sector, and so poor in the public sector, that total private sector employment has fully recovered to pre-pandemic levels, while government employment has remained consistently low.7

A longer-term decline in public employment over the last 15 years has been driven primarily by budget and tax cuts that have reduced the number of public sector jobs in the state. Another particularly important contributor in the current labor market is the low pay and reduced benefits in the public sector.8 While state employee pay recently improved after the General Assembly approved an 8% raise in 2022, the staffing shortage remains high and stems from significantly less generous benefits than in the past and an outdated pay grade system. Addressing total compensation through improved benefits and an overhaul of the pay grade system that results in higher wages with sustained cost of living adjustments will be necessary to increase the state workforce and improve retention.9

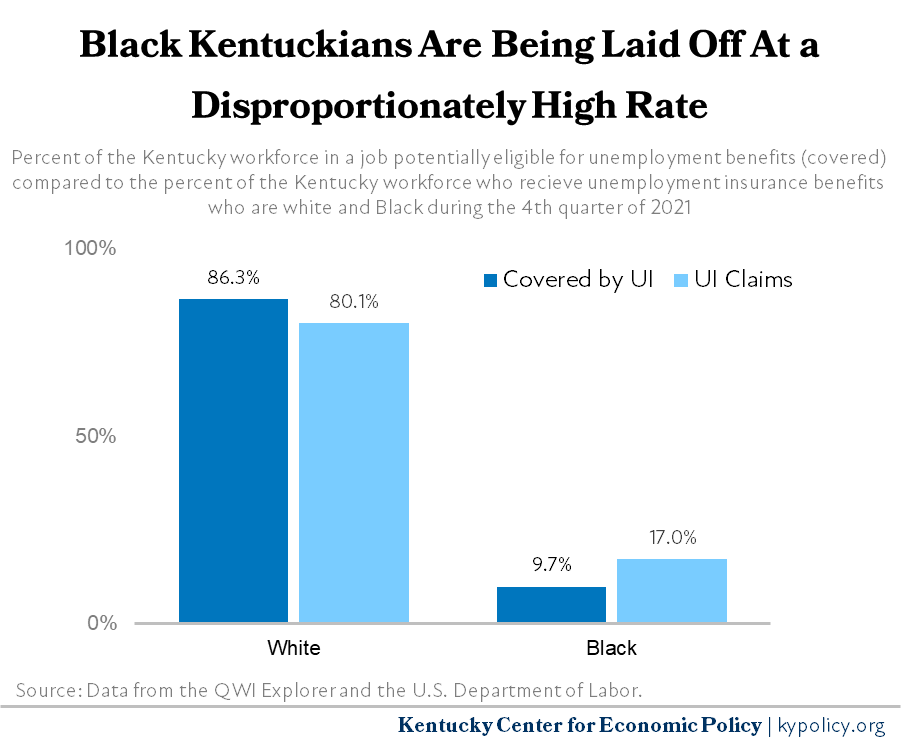

When broken out by race, the uneven recovery is also stark, with evidence that Black Kentuckians were laid off at a disproportionately high rate in the COVID-19 recession. As of the 4th quarter of 2021 (the most recent data available disaggregated by race) total employment among employees was still 0.1% below the first quarter of 2020 (before pandemic-related job losses hit the economy). However, employment among white Kentucky employees was 0.2% below the first quarter of 2020, while the number of Black employees was 2.2% below.10

When looking at Kentuckians who claim unemployment benefits, meaning they have a work history but have been laid off through no fault of their own, Black workers were laid off at a disproportionately high rate into the 4th quarter of 2021 (the most recent data available):

- 17.0% of Kentucky unemployment insurance claimants were Black workers despite making up 9.7% of the workforce covered by unemployment insurance.

- 80.1% of Kentucky unemployment insurance claimants were white workers despite making up 86.3% of the workforce covered by unemployment insurance.11

When looking at job growth by geography, the picture is extremely divergent between rural and urban counties. While the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic is still underway and scattershot, looking back 15 years to before the Great Recession shows a consistently bleak picture for rural counties, which have collectively lost nearly 76,000 jobs or 9.8% of employment since 2007. At the same time, urban counties have added over 116,000 jobs, or 9.9% growth.12 In part, this reflects a long decline in traditional industries such as manufacturing and mining in rural counties, and the jobs they supported. Mining employment in eastern Kentucky fell from 13,372 in 2007 to 2,797 by the first quarter of 2022.13 At the same time, service sector positions, which are disproportionately located in urban counties, grew rapidly.

Kentucky has made substantial progress in improving participation in the labor force since the worst part of the COVID crisis. In February 2020, Kentucky’s labor force participation rate (those working and those looking for work compared to the whole civilian population age 16 and up) was 58.6% and by June 2020 it had bottomed out at 54.7%. As of July 2022, it has recovered to 58.1%, roughly 2,700 fewer people than before the pandemic out of a labor force of over 2 million.14

However, there are still barriers for some to join the workforce that existed before the downturn and have only worsened since. Women were particularly hard-hit during the downturn. Men nearly always comprise the majority of unemployment insurance claims in Kentucky, but women made up the majority for five months during 2020, an unprecedented stretch. This phenomenon was primarily due to women making up the majority of the industries hit hardest by 2020 job losses.15 By the 4th quarter of 2021 (the most recent quarter for which data disaggregated by sex is available), employment among male employees was 1.3% above pre-pandemic levels (Q1 2020), while employment for women was still 1.4% below.16

A primary barrier for many women (and men to a lesser degree) returning to the workforce is a lack of available and affordable child care. National labor force participation statistics from December 2021 illustrate that barrier. They showed that 70% of prime-age mothers of children under 5 years old were working, compared to 80% of mothers of children age 5-17, and over 90% of fathers of children at any age.17 While many mothers may voluntarily stay home with young children, 12.6% of children age 5 and under had a caregiver who reported an employment disruption related to child care.18 Among women outside the workforce and not seeking employment, over a third reported that lack of available child care was the reason.19 Kentucky is not an exception to this phenomenon, as half of the state is a child care desert with little to no child care availability nearby; 46% of centers have closed their doors over the past decade, and for those who can find child care, it often costs as much as public university tuition.20

Retirees are another group that has increasingly left the labor force. The share of Americans who are retired has been on the rise since 2010 as baby boomers aged out of the workforce, but that increase accelerated when COVID hit.21 This trend will continue as Kentucky’s population ages over time, with the share of Kentuckians age 65 and older increasing from 17.1% in 2020 to 20.1% of the population in 2035.22

A tight labor market and high inflation are creating mixed results for job quality and wages

While businesses have been hiring at a blistering pace, they have also reported a large number of openings as they attempt to keep up with steady demand. The number of Kentuckians looking for work who are not currently employed (which is what being unemployed means) is also historically low, putting pressure on employers to make their positions attractive to potential applicants.

One way to measure this “tightness” in the labor market is to compare the number of Kentuckians who are looking for a job to the number of available job openings.23 In 2012, there were far more workers looking for a job than available jobs. But because of a steady rate of hiring over the next several years, by the end of 2017 it was roughly 1:1, and remained so until the worst of the downturn. So far in 2022, however, there have been nearly twice as many open positions than unemployed workers, evidence of a tight labor market.

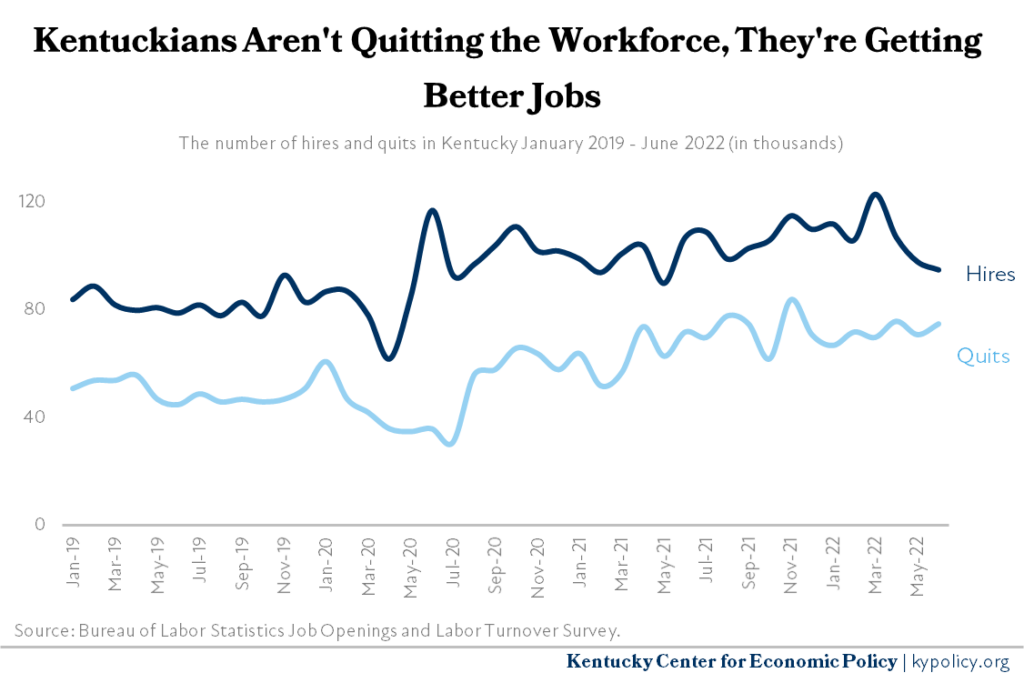

This combination of a large number of openings and very few unemployed job-seekers has allowed some currently working to leave their positions in favor of jobs that pay better, offer better benefits or offer more flexibility. In fact, while the number of workers who voluntarily quit their jobs has risen to historically high levels, hires have significantly outpaced quits every month in Kentucky. Since the recovery began in May 2020, there have been 40,000 more hires than quits every month on average.24

The result of this “great reshuffling” has been badly needed and long overdue raises, particularly for low- and middle-income earners. Recently increasing wages are both a product of people moving to higher-paying jobs, and employers raising wages to retain the employees they already have. But for most workers in Kentucky, wages have been stagnant over much of the past few decades, meaning the increases over the past couple years have not made up for already too-low wages. Prior to 2019, the average annual wage in Kentucky was essentially unchanged going back to 2015 (the average wage was $49,577 and $49,964 in 2015 and 2018 respectively). But an increasingly tight labor market in Kentucky pushed the average annual wage higher in 2019, when it increased 1.3% over the previous year. It rose another 4.5%, to $52,860, between 2019 and 2021 as employers began rehiring post-pandemic.25 The average, however, is much higher than the median, which is an annual $40,165 for a full-time employee.26 This is largely due to the fact that Kentuckians in the top 10% of earners make double the median wage and 4 times the bottom decile on average.

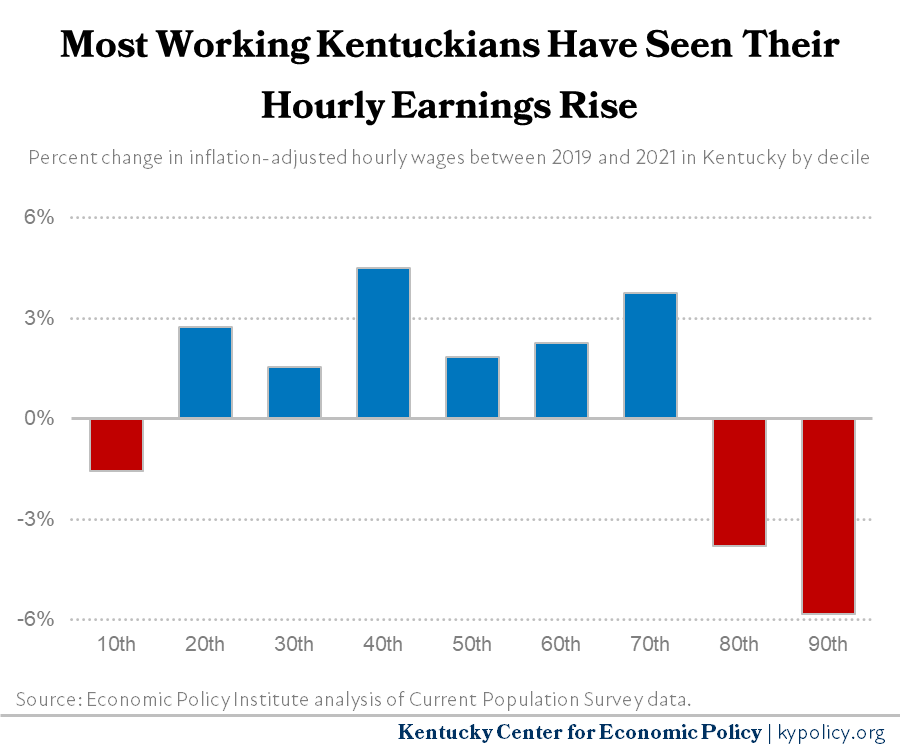

Unlike the past, when higher-earners’ incomes rose more quickly than middle- and lower-wage-earning Kentuckians, those at the top have not been the primary beneficiaries of a tighter labor market (although those with significant stock portfolios gained substantial investment income from strong financial markets through the end of 2021). For example, although the top 20th percentile of earners in Kentucky actually saw their inflation-adjusted wages fall between 2019 and 2021, Kentucky workers in the 20th-70th percentiles saw inflation-adjusted hourly wage gains anywhere between 1.5% and 4.5%.

This tighter-than-usual labor market has been met with some increase in unionization efforts as workers gain more confidence to organize given a wider range of options if they should get fired for speaking out. While the rate of Kentucky workers covered by a union has significantly fallen over the past 25 years — 2020 marked a low point of 9.3% — recent activity within existing unions and in the development of new unions made 2021, when 9.7% of Kentucky workers were in unions, the first in five years without a decrease in union coverage.27 The staff of the Courier-Journal, an Amazon warehouse, public defenders in Louisville and various coffee shops have recently made headlines in Kentucky for their efforts to form new unions.28

Despite wage gains, price increases are making it harder for families to make ends meet

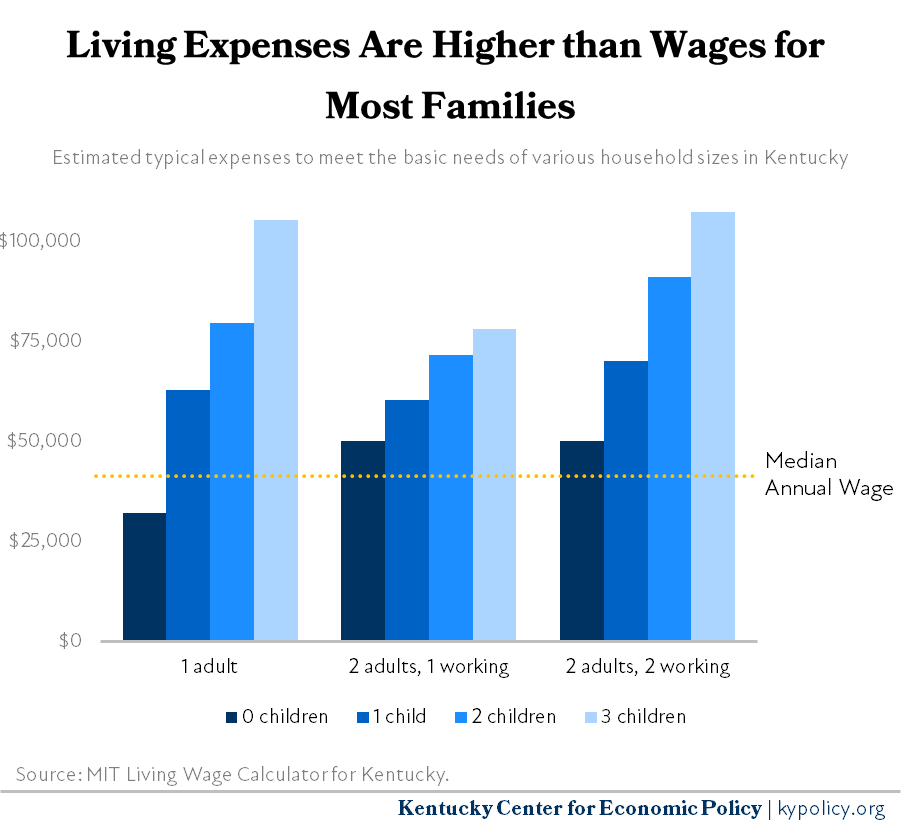

Even with recently rising wages, typical pay in Kentucky is not sufficient to adequately meet a family’s financial needs. Researchers at MIT, for example, routinely update the minimum income needed to cover basic family expenses at different household sizes at the state and local level. In Kentucky, the median annualized full-time wage of $40,165 is not enough to cover the basic needs of families with children, particularly single-parent households and households with only one employed parent. While a single adult without children can get by on $32,147 per year, a family of 5 with both parents employed need $107,389 before taxes.29 Food, housing and transportation are all significantly more expensive for households with children, particularly two or more children. However, child care is the most significant expense, and most jobs don’t pay well enough for one parent to stay at home with their children, making it a necessary and large expense.

The statewide average cost of living masks the disparity in family budget needs based on where in the state you live. Some areas, particularly in urban counties, have much higher costs of living than others. For example, according to the Family Budget Calculator from the Economic Policy Institute, it is 36% more expensive for a family of 4 to live in Boone County than it is to live in Knox County, with housing costs as the primary driver of that difference.30 However, there are also expenses unique to living in rural areas, including the transportation costs associated with access to basic amenities.

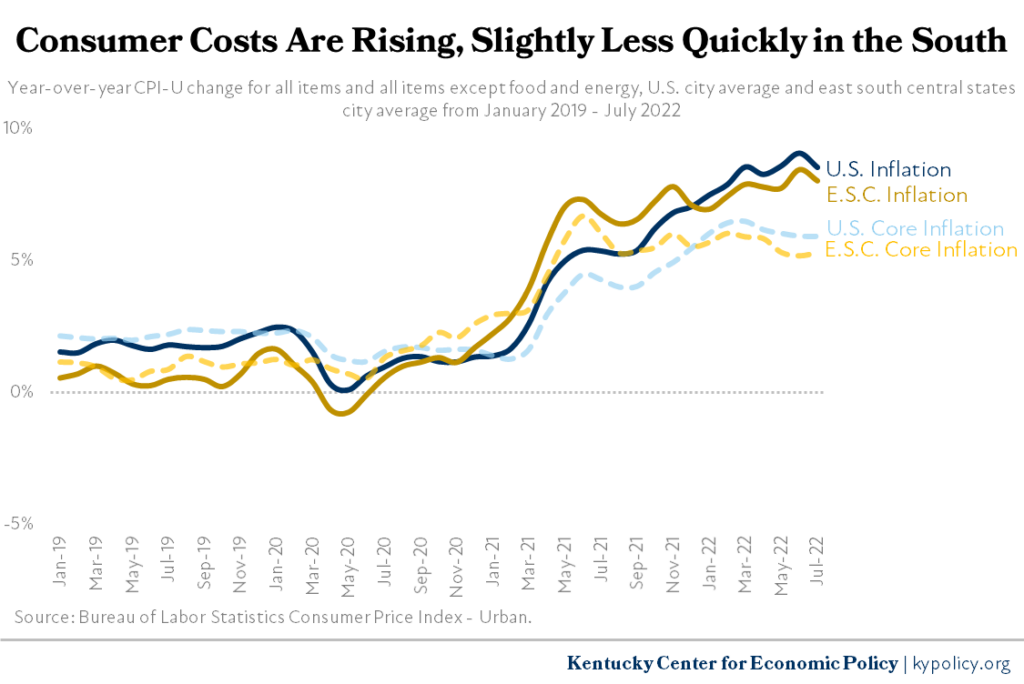

The high cost of living relative to the median wage in Kentucky is exacerbated by the fact that inflation has made it harder to afford basic needs. In the east south central states — which include Kentucky — year-over-year inflation was 8.0% in July, which was slightly down from June, but still close to the highest it has been for decades. Core inflation, which doesn’t include food or energy prices, was 5.3%. This increase in everyday costs has been disproportionately hard on lower-earning households, who have to spend a greater share of their income than wealthier families in order to meet their basic needs.31 Additionally, although personal consumption expenditures remain high, the personal savings rate at the national level was 5.0% of disposable income as of July 2022, which is below pre-pandemic levels of between 7% and 8%, and total national personal savings is roughly 2/3 of what it was February 2020.32 This means families have even less of a cushion to fall back on in the face of rising prices.

While Kentucky’s regional price increases have recently been slightly lower than the national average for inflation, they are still high and in some cases outpace wage growth. The fact that wages are not keeping up with inflation means that wage increases are not exacerbating inflation through what is known as a “wage-price spiral.” That would involve higher wages leading businesses to raise prices in order to cover higher labor costs, which in turn would create pressure on employers to further raise wages so their employees could afford living expenses, and so on. Instead, we’re seeing wages not even keeping up with the rise in prices. This means that slower wage growth is actually putting downward pressure onprice growth.33

Inflation stems from many causes, but there have been two major shocks over the past two years that have been major contributors. First, the spike in prices was the result of a switch from buying services to buying goods at the same time people all around the world were not making those goods because they were trying to avoid getting COVID.34 Since 2020, the entire world’s production and supply chain has been playing catch-up, with factories coming back online, transportation struggling to move things quickly enough and ports backing up with shipping containers.35 This dip in supply was not met with lower demand, and so costs rose. More recently, the shift has turned back toward an uptick in purchasing services, particularly travel, which has led to further price increases in those sectors as well.36

The second shock to prices was the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Russia and Ukraine collectively produce about 30% of the world’s wheat, 20% of the world’s corn, fertilizer and natural gas, and 11% of the world’s oil.37 With financial sanctions making the transactions of these commodities difficult in Russia, the Russian blockade of Ukrainian ports preventing the export of agricultural commodities and the general disruption that an active war causes in the production of crops, the war in Ukraine is having a severe impact on global food and energy prices.

In contrast, federal fiscal stimulus in the United States was not a major contributor to inflation, and is a major reason why the economy did not slip into a depression.38

Continued hardship and decreasing federal, state aid leaves Kentucky vulnerable to economic harm

Federal relief programs from 2020 and 2021 have poured $45.5 billion into Kentucky over the past 2 years, which has kept our economy afloat.39 But much of this money has already been spent by individuals, businesses and state and local governments, with very little left for future disbursement.40 Thus, while consumer demand and new hiring are high now, the policies driving the economy are in reverse, and long-term supports will continue to be necessary to address future downturns and individual crises.

As federal fiscal stimulus related to COVID-19 is winding down, the Federal Reserve has been aggressively raising interest rates in an attempt to bring down inflation.41 Higher interest rates lead to lower business investment, which in turn can (and often has) resulted in lower rates of hiring, higher rates of layoffs and more unemployment. The potential for lower employment and less consumer demand point toward the possibility of a recession in the coming months, but whether that actually happens remains uncertain.

Regardless of the potential for a recession, many families are already finding it difficult to make ends meet. This is particularly true among families with children, nearly half of whom report they are having difficulty affording usual expenses, up from a third in August of last year.42 Maintaining a robust set of supports through food, medical and basic cash assistance are critical to alleviating that hardship. Although many people are returning to work, and many others are seeing wage gains, the recovery is not being felt everywhere, and many Kentuckians still need help.

Among those in need of assistance are Kentuckians whose lives were disrupted by the recent natural disasters in western and eastern Kentucky. Some disaster-specific aid like the Disaster-Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and Disaster Unemployment Assistance are quickly available to those whose incomes and lives have been disrupted in the immediate aftermath of a disaster.43 Aid provided through FEMA was also quickly deployed, but woefully inadequate for sustaining a family or rebuilding a home.44 Recovering from these and future natural disasters takes years, and preserving the public assistance programs is especially important for these communities, and more like them as climate change increases the frequency and severity of such disasters.

While Kentucky has been recovering from the pandemic and natural disasters, talk of a “worker shortage” (which, as has already been mentioned, is simply a tight labor market putting upward pressure on wages) has been used to justify harmful cuts to safety net and unemployment insurance programs. These claims are unjustified given the historically rapid rise in hires, and the lingering hardship from the pandemic.45 Far from being a hindrance to participation in the workforce, public assistance programs like SNAP, Medicaid and the Child Care Assistance Program support workers and their families as they struggle under low wages and underemployment.

This is especially true of unemployment insurance, which has a track record of improving job quality among claimants in states with generous programs, and reducing the harmful effects of economic downturns.46 Yet during the 2022 General Assembly, lawmakers passed House Bill 4, which severely undermines those benefits, under the misguided assumption that Kentucky’s labor force required benefit cuts to compel laid off workers to take jobs more quickly. The legislation deeply weakens the effectiveness of unemployment insurance by cutting the maximum available weeks a worker could claim benefits by up to 54%, ramping up burdensome reporting requirements and new complex rules, and requiring that recently laid-off Kentuckians take any job available — even if it pays roughly half of what their previous job paid. The restricted number of weeks unemployment benefits would be available is based on the statewide unemployment rate from anywhere between 3 and 12 months prior to when a laid-off worker files a claim. For example, should a worker file for unemployment benefits next June, the number of weeks available to them would be based on the unemployment rate in July-September of this year, when the unemployment rate is at a 50-year low. In fact, if HB 4’s indexing scheme had been in place in the first half of 2020, when unemployment exceeded 15% of the labor force, just 12 weeks of benefits would have been available.47 This leaves Kentucky’s economy dangerously unprepared for the next recession, and Kentucky’s families vulnerable to job loss at any time.

Lawmakers should act to improve the quality of life, and work, in Kentucky

Despite the benefits of the tight labor market on wages, the effects of inflation, threat of recession and impact of decades of stagnant wages mean more should be done to help Kentuckians make ends meet and to improve job quality. While the policy needs are not new, the shifting context adds urgency to how badly Kentuckians need better policies.

Help Kentucky families weather rising prices with policies that lower family costs

As already stated, one of the largest expenses families face is child care, which averages 17% of household median income for families with one toddler.48 For many families, child care is not even available nearby, let alone affordable; half of Kentucky’s kids live in a child care desert, where there are either no child care spots available nearby, or there are at least three times as many kids as available spots.49 Yet child care is consistently one of the most important components of consistent employment, especially for mothers.50 While Kentucky’s Child Care Assistance Program helps approximately 18,000 children each year, it and the rest of the child care industry is being sustained by a massive amount of federal money through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), which will expire in the next two years. The ARPA funding has allowed the state to raise the income eligibility threshold, provide a phase-out for those no longer eligible, increase reimbursement rates to providers, incentivize providers to pay their workers more and improve the quality of care at centers. When that funding expires in two years, it will be incredibly difficult for many child care centers to remain open without significantly raising rates, which are already unaffordable for most families.51 Additional federal or state funds will be absolutely critical to staving off that coming fiscal cliff.

Another need for families with very low incomes, those harmed the most by rising consumer prices, is more robust basic cash assistance. Our basic cash assistance program, known as the Kentucky Transitional Assistance Program (KTAP), provides roughly $100 per person, per month for up to 60 months, an amount that has not been adjusted for inflation since before the program was reformed at the federal level in 1996. Additionally, the income eligibility limit is based on a dollar amount, not indexed to the federal poverty level or median income, and so has effectively shrunk each year with inflation. This has resulted in a long, steady decline in the value of the program and the number of people it serves, with just 3,400 adults and 16,900 children currently participating.52 The program can be improved in several ways including raising the benefit amount and income threshold, phasing benefits out more gradually so as to not penalize participants for earning income, and removing several arcane rules that predate 1996 welfare reform and keep families from participating.

Kentucky can also help families afford basic costs through cash assistance in the form of a state-level child tax credit (CTC) and earned income tax credit (EITC). The temporary monthly federal CTC cut child poverty nearly in half in Kentucky, but unfortunately Congress let it expire at the end of 2021.53 So far nine states have enacted and funded state CTCs that provide hundreds of dollars of aid to families.54 The EITC provides additional income to low-wage workers based on family size, and 30 states have enacted state versions of that program.55

Support workers and the economy with policies that raise wages

One policy that would have an immediate impact on wages in Kentucky is raising the minimum wage, which has not been increased in 13 years. This is the longest it has been since the most recent increase in the history of the minimum wage, and as a result, the value of today’s $7.25 minimum wage is the lowest it has been since 1956, and 27.4% lower than it was when it was last increased.56 While the regular minimum wage is extremely low, tipped workers face an even lower minimum wage of $2.13 per hour, a level that has not been increased since 1991.57 Additionally, employers are allowed to pay Kentuckians with disabilities and some other groups less than the federal minimum wage after obtaining a certificate from the U.S. Department of Labor.58 Kentucky should ban that practice, as disability advocates have sought and as other states have recently done, ensuring a true minimum wage for all workers in the commonwealth.59

If Kentucky were to raise the minimum wage to $15 per hour by 2025, an estimated 1 in 4 Kentucky workers would get a raise to that amount, and 1 in 3 would get a raise of some kind, as some higher earners would need further increases reflecting their seniority or managerial status. This would result in an average wage increase of $4,182 per year (19.3%) for those affected. In total, this would lead to $2.7 billion more in wages, which would spur demand and increase economic activity across the state.60

Though not directly a wage increase, paid sick and parental leave ensures workers don’t lose wages when they or loved ones are sick, or even lose a job when they have a baby. But Kentuckians are not guaranteed any paid parental or sick leave. In 2021, 71% of workers in east south central states — which includes Kentucky — reported access to paid sick leave, and just 20% reported their job offered paid parental leave. For lower-wage employees, it’s far worse: Just 53% and 12% of workers (nationally) in the bottom quartile of earners report having a job with paid sick and parental leave, respectively.61

There are 14 states and the District of Columbia that have laws requiring employers to provide paid sick leave, but Kentucky is not one of them.62 Paid parental leave not only helps new parents recover and adjust to life with children (or additional children), but it also improves attachment to the labor force. First-time mothers who use employer-provided paid leave are 26% less likely to quit their jobs after giving birth than mothers who do not have paid leave.63

Wages can also be improved by making sure people get the hours they need. About 2 in 5 workers nationally know their schedule less than one month in advance, and roughly 1 in 5 have less than a week’s notice of their work schedule. Workers without a high school degree, and those who are Black or Hispanic are even more likely to have little notice of their work hours.64 Additionally, many employees are required to work “split shifts,” where they must work two shifts in the same day with a significant gap in between, or “clopening” shifts, where an employee must close the business and then open the next morning. Even worse, some employers use “just-in-time” scheduling, wherein an employee may be called in the same day without advance notice, or sent home early without pay, depending on how busy the employer is at that time.65 These practices can be extremely disruptive to employees and tend to land most frequently on those in the leisure and hospitality or retail industries, which employ 199,900 and 211,000 Kentuckians, respectively — a combined 21% of all non-farm employment in Kentucky.66 Other states have addressed these issues through laws that give employees the right to request changes to their schedules, advance notice of schedules, guaranteed pay for schedules regardless of whether shifts are cut after the fact, additional compensation for required split shifts, and minimum rest time between shifts.67

Finally, the recent efforts to unionize have been promising, but face headwinds in the commonwealth. Workers covered by a union have wages that are approximately 23% higher than non-union workers, and are able to negotiate for safer working conditions.68 Yet, employers and lawmakers have successfully weakened workers’ rights to organize over the past several years, including by passing so-called “right-to-work” legislation in Kentucky in 2017. Additionally, illegal union-busting activities are rampant, with employers charged with unlawful activities including firing, threatening or retaliating against employees who are attempting to unionize in 41% of all union election campaigns. Most of the ways unionization efforts can be supported are at the federal level, such as stricter enforcement of anti-union-busting laws, reforming the National Labor Relations Act and passing the Protecting the Right to Organize Act.69 The state can also help by repealing “right-to-work” and giving preference to state vendors with a unionized workforce in the contracting process.

Support growth of good jobs in the public sector by investing in the public workforce

Because public sector workers operate across the state, their incomes are also an investment in local economies, particularly in rural parts of the state where private-sector incomes are low and private-sector jobs are less common. The lack of growth in government employment during the COVID recovery, as described above, is a drag on the overall economy. It’s part of a longer trend that has seen state budget cuts and lack of raises reduce the state workforce by 34.6% over the past 30 years, despite the state population (and therefore the need) growing 21.1% over the same period of time.70

Kentucky now has $2.7 billion in its Budget Reserve Trust Fund that it can use to begin rehiring key positions to address pressing needs, including flood prevention, the opioid crisis, education and more.

The monies can also be used to address the crisis in public sector compensation. Public employees tend to earn less than private sector workers in total compensation, a problem that has worsened over the past decade because of multiple rounds of budget cuts.71 The 2022 General Assembly provided the first meaningful state employee raise in 14 years, and set aside money to provide an additional raise in 2023 based on the recommendations of the Personnel Cabinet. Additional compensation and improved benefits will be necessary to attract and retain an adequate workforce. Moving forward, the state also needs to address several compensation equity issues laid out in the Personnel Cabinet’s report to the General Assembly, including fixing wage compression in several agencies, addressing the pay grade scale and returning to annual cost of living adjustments.72

In addition, the state needs to fund raises for school employees, such as bus drivers and cafeteria workers, along with teachers, whose average wages have fallen 8.1% since 2008 and even further in some poorer counties.73 A shortage in these positions is a real and growing problem that weakens job opportunities locally and will make the state’s economy less productive in the long term. The legislature did not fund school employee raises in the budget, and many school districts were not able to afford adequate raises with the limited increase in state funding the legislature provided.74

- Dustin Pugel, “Kentucky’s Jobs Recovery is Very Strong – False Claims to the Contrary Are Being Used to Justify Harmful Benefit Cuts,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Feb. 21, 2022, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-jobs-recovery-is-strong-false-claims-to-the-contrary-being-used-to-justify-benefit-cuts/. The state has averaged job growth of 6,200 since July of 2020, which is after the initial call-back of workers after the governor’s healthy at home orders largely phased-out. If May and June are included, the average monthly job growth rises to 10,200.

- Dustin Pugel, “Federal Relief Programs Cut Poverty in Kentucky by Two-Thirds This Year,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Aug. 5, 2021, https://kypolicy.org/federal-relief-programs-cut-poverty-in-kentucky-by-two-thirds-this-year/.

- Laura Wheaton, Linda Giannarelli and Ilham Dehry, “2021 Poverty Projections: Assessing the Impact of Benefits and Stimulus Measures,” Urban Institute, July 2021, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104603/2021-poverty-projections_0_0.pdf.

- Personal Consumption Expenditures data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’ Federal Reserve Economic Data, accessed on July 27, 2022, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PCE.

- Josh Bivens, “Cutting off the $600 Boost to Unemployment Benefits Would Be Both Cruel and Bad Economics,” Economic Policy Institute, June 26, 2020, https://www.epi.org/blog/cutting-off-the-600-boost-to-unemployment-benefits-would-be-both-cruel-and-bad-economics-new-personal-income-data-show-just-how-steep-the-coming-fiscal-cliff-will-be/.

- Peter Ganong et. al., “Spending and Job-Finding Impacts of Expanded Unemployment Benefits: Evidence From Administrative Micro Data,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Aug. 2022, https://www.nber.org/papers/w30315.

- The dip in July for government jobs reflects a routine decline in jobs for local governments in July each year, likely stemming from temporary layoffs in school districts.

- Dustin Pugel and Pam Thomas, “A Decade Without Raises and Weakened Benefits Have Created a State Workforce Crisis. Addressing it Adequately Should Be a Top Priority in the New Budget,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 11, 2022, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-state-workforce-crisis-should-be-a-top-priority-in-2022-2024-budget/.

- Dustin Pugel and Pam Thomas, “Personnel Cabinet Recommends Improving Compensation to Stave off State Workforce Crisis,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, July 13, 2022, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-personnel-cabinet-recommends-improving-compensation-to-stave-off-state-workforce-crisis/.

- KyPolicy analysis of data from the Census Bureau’s Quarterly Workforce Indicators application, accessed Aug. 31, 2022.

- KyPolicy analysis of data from the Census Bureau’s Quarterly Workforce Indicators application and Characteristics of the Unemployment Insurance Claims from the U.S. Department of Labor, accessed Aug. 31, 2022.

Dustin Pugel, “Black Kentucky Workers Are More Likely to Have Been Laid Off in the Pandemic, and Less Likely to Have Been Hired Since,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Sep. 11, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/black-kentucky-workers-are-more-likely-to-have-been-laid-off-in-the-pandemic-and-less-likely-to-have-been-hired-since/. - KyPolicy analysis of June 2007 and June 2022 Local Area Unemployment Statistics for Kentucky and Rural Classifications from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service.

- Kentucky Department for Energy Development and Independence, “Kentucky Coal Facts 11th Edition,” 2011, https://eec.ky.gov/Energy/Coal%20Facts%20%20Annual%20Editions/Kentucky%20Coal%20Facts%20-%2011th%20Edition%20(2009-2010).pdf.

Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet, “Kentucky Quarterly Coal Report (2022-Q1),” https://eec.ky.gov/Energy/News-Publications/Quarterly%20Coal%20Reports/2022-Q1.pdf. - KyPolicy analysis of seasonally-adjusted Local Area Unemployment Statistics data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- Sam Keathley, Barett Ross and Kris Stephens, “Kentucky Labor Force Update: Gender Employment Disparities During the Coronavirus Pandemic,” Kentucky Center for Statistics, Dec. 23, 2020, https://kystats.ky.gov/Content/Reports/WP-LF_Update_December_2020.pdf?v=20210127061933.

- KyPolicy analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Quarterly Workforce Indicators application.

- Ana Hernandez Kent and Sam Evans, “Child Care Remains Central to an Equitable Recovery,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Feb. 17, 2022, https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2022/feb/child-care-remains-central-equitable-recovery?utm_source=Federal+Reserve+Bank+of+St.+Louis+Publications&utm_campaign=12f86329df-BlogAlert&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_c572dedae2-12f86329df-57450045.

- Caleb Easterly et. al., “Childcare and Employment Disruptions in 2020 Among Caregiviers of Children With and Without Special Health Care Needs,” JAMA Pediatrics, June 13, 2022, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2792832?guestAccessKey=a859b3db-bf05-4fb3-b30a-ff56a29fabae&utm_source=For_The_Media&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=ftm_links&utm_content=tfl&utm_term=061322.

- AnnElizabeth Konkel, Svenja Gudell and Tara Sinclair, “Women Lag Men in Pandemic Economic Recovery,” Hiring Lab, July 18, 2022, https://www.hiringlab.org/2022/07/18/women-lag-pandemic-economic-recovery/.

- Dustin Pugel, “Child Care in Kentucky is Crucial and in Dire Need of Public Investment,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Nov. 11, 2021, https://kypolicy.org/report-child-care-in-kentucky-is-crucial-and-needs-public-investment/.

- Miguel Faria e Castro, “The COVID Retirement Boom,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Oct. 15, 2021, https://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/economic-synopses/2021/10/15/the-covid-retirement-boom.

- KyPolicy analysis of Vintage 2022 Projections of Population and Households from the Kentucky State Data Center, accessed Aug. 31, 2022, http://ksdc.louisville.edu/data-downloads/projections/.

- David Andolfatto and Serdar Birinci, “Is the Labor Market as Tight as it Seems?” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, June 21, 2022, https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2022/jun/is-labor-market-as-tight-as-it-seems?utm_source=Federal+Reserve+Bank+of+St.+Louis+Publications&utm_campaign=74ec78ede3-BlogAlert&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_c572dedae2-74ec78ede3-57455617.

- The remainder of the difference between the outpacing of hires to quits and the monthly job growth numbers are discharges and layoffs. For example, quits, discharges and layoffs in May 2022 totaled 92,000 (of which, quits were 67,000), while hires totaled 96,000.

- KyPolicy analysis of data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages.

Note: The average wage in 2020 was higher than in 2021, but that is likely due to changes in the composition of the workforce as lower-paying jobs were laid off in greater numbers than higher-paying jobs, skewing the average upward, rather than reflecting a real change in wages. - Data from Economic Policy Institute’s analysis of data from the Current Population Survey. Assumes 40 hours a week for 52 weeks a year at the median hourly wage of $19.31.

- Economic Policy Institute analysis of data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- Chris Otts, “‘Louisville Deserves Better’ Courier Journal Newsroom to Unionize,” WDRB, Aug. 30, 2022, https://www.wdrb.com/news/business/louisville-deserves-better-courier-journal-newsroom-to-unionize/article_661b207c-2898-11ed-a107-13973c884b87.html.

Leah Hunter, “Why an Amazon Worker at a Kentucky Facility is Trying to Unionize his Workplace,” Lexington Herald-Leader, July 12, 2022, https://www.kentucky.com/news/business/article263286438.html.

Jared Bennett, “Louisville Public Defenders Claim ‘Retaliation’ Against Union Effort,” Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting, May 23, 2022, https://kycir.org/2022/05/23/louisville-public-defenders-claim-retaliation-against-union-effort/.

Dakota Sherek, “Heine Brothers’ Workers File for Election in Effort to Get Union Recognized,” WDRB, July 25, 2022, https://www.wdrb.com/news/heine-brothers-workers-file-for-election-in-effort-to-get-union-recognized/article_056eb45e-0c60-11ed-a239-171170d493c9.html.

Adam Raymond, “Louisville Starbucks Is First in Kentucky to Unionize,” May 27, 2022, https://spectrumnews1.com/ky/louisville/news/2022/05/27/louisville-starbucks-is-first-in-kentucky-to-unionize.

Ana Rocío Álvarez Bríñez, “Baristas and Other Employees With Another Louisville Coffee Company Say They’re Unionizing,” Courier-Journal, Aug. 26, 2022, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/local/2022/08/26/louisville-sunergos-coffee-employees-union-push/65458305007/. - Amy K. Glasmeier, “Living Wage Calculator for Kentucky,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology, May 20, 2022, accessed on Aug. 8, 2022, https://livingwage.mit.edu/states/21.

- Elise Gould and Zane Mokhiber, “Family Budget Map,” Economic Policy Institute, March 1, 2022, accessed Aug. 8, 2022, https://www.epi.org/resources/budget/budget-map/.

- KyPolicy analysis of the Consumer Price Index for Urban All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), accessed on Aug. 31, 2022, https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm.

Jeanna Smialek and Ben Casselman, “In an Unequal Economy, the Poor Face Inflation Now and Job Loss Later,” New York Times, Aug. 8, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/08/business/economy/inflation-jobs-economy.html. - Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Federal Reserve Economic Data, Personal Saving Rate, accessed Aug. 24, 2022, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PSAVERT.

KyPolicy analysis of Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Federal Reserve Economic Data, Personal Saving seasonally-adjusted data for February 2020 and July 2020, accessed Aug. 26, 2022, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PMSAVE. - Josh Bivens, “Wage Growth Has Been Dampening Inflation All Along – and Has Slowed Even More Recently,” Economic Policy Institute, May 12, 2022, https://www.epi.org/blog/wage-growth-has-been-dampening-inflation-all-along-and-has-slowed-even-more-recently/.

- Kristen Tauber and Willem Van Zandweghe, “Why Has Durable Goods Spending Been So Strong During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, July 7, 2021, https://www.clevelandfed.org/en/newsroom-and-events/publications/economic-commentary/2021-economic-commentaries/ec-202116-durable-goods-spending-during-covid19-pandemic.aspx.

- Justin Ho, “Port Congestion is Easing. But Supply Chain Congestion Isn’t Going Away Soon,” Marketplace, June 10, 2022, https://www.marketplace.org/2022/06/10/port-congestion-is-easing-supply-chain-still-congested/.

- David J. Lynch, “Consumers Are Shifting Their Spending From Goods to Services,” Washington Post, May 28, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2022/05/27/consumer-spending-goods-services/.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, “The Price of War: OECD Economic Outlook June 2022,” June 2022, accessed Aug. 2, 2022, https://www.oecd.org/economic-outlook/.

- Josh Bivens, Asha Banerjee and Mariia Dzholos, “Rising Inflation is a Global Problem, U.S. Policy Choices Are not to Blame,” Economic Policy Institute, Aug. 4, 2022, https://www.epi.org/blog/rising-inflation-is-a-global-problem-u-s-policy-choices-are-not-to-blame/.

- Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, “COVID Money Tracker,” accessed Aug. 9, 2022, https://www.covidmoneytracker.org/.

Note: This includes funds from legislative, administrative and Federal Reserve actions. - Ashley Spalding, Dustin Pugel and Jason Bailey, “Budget Agreement Includes Only Modest Increases in Most Areas of Budget, Salary Increases for State Workers,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, March 29, 2022, https://kypolicy.org/budget-agreement-includes-only-modest-increases-in-most-areas-of-budget-salary-increases-for-state-workers/.

- Christopher Rugaber, “Fed Unleashes Another Big Rate Hike in Bid to Curb Inflation,” Associated Press, July 27, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/federal-reserve-interest-rate-hike-live-updates-6dab38b8235bc62bdf69b4710c6b84f5.

- Patrick Drake and Elizabeth Williams, “A Look at the Economic Effects of the Pandemic for Children,” Kaiser Family Foundation, Aug. 5, 2022, https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/a-look-at-the-economic-effects-of-the-pandemic-for-children/.

- United States Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service, “Kentucky Disaster Nutrition Assistance,” July 26, 2022, accessed Aug. 9, 2022, https://www.fns.usda.gov/disaster/kentucky-disaster-nutrition-assistance.

Crystal Staley, “Gov. Beshear: Disaster Unemployment Assistance Available for Those Impacted by Severe Storms, Flooding in Eastern Kentucky,” Office of the Governor of Kentucky, Aug. 4, 2022, https://kentucky.gov/Pages/Activity-stream.aspx?n=GovernorBeshear&prId=1445. - Jason Bailey and Pam Thomas, “State Must Go Beyond FEMA Aid to Adequately Address Housing Need From Eastern Kentucky,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Aug. 22, 2022, https://kypolicy.org/state-must-address-housing-need-eastern-kentucky-floods/.

- Dustin Pugel, “Kentucky’s Jobs Recovery is Very Strong – False Claims to the Contrary Are Being Used to Justify Harmful Benefit Cuts,” Feb. 21, 2022.

- Arash Nekoei and Andrea Weber, “Does Extending Unemployment Benefits Improve Job Quality?” American Economic Review Vol. 107 (2), Feb. 2017, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20150528.

William J. Congdon and Wayne Vroman, “Extending Unemployment Insurance Benefits in Recessions: Lessons from the Great Recession,” Urban Institute, Feb. 2021, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103720/extending-unemployment-insurance-benefits-in-recessions-lessons-from-the-great-recession_2.pdf. - Dustin Pugel, “HB 4 Would Slash Unemployment Benefits, Harming the Economy and Deeping Hardship for Kentucky Workers,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Feb. 4, 2022, https://kypolicy.org/hb-4-would-slash-unemployment-benefits-harming-economy-and-deepening-hardship-for-kentucky-workers/.

- Dustin Pugel, “Child Care in Kentucky Is Crucial and in Dire Need of Public Investment,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Nov. 11, 2021, https://kypolicy.org/report-child-care-in-kentucky-is-crucial-and-needs-public-investment/#easy-footnote-bottom-23-17477.

- Rasheed Malik et. al., “America’s Child Care Deserts in 2018,” Center for American Progress, Dec. 6, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/reports/2018/12/06/461643/americas-child-care-deserts-2018/, https://childcaredeserts.org/2018/?state=KY.

- Lowell Ricketts, “Child Care and School Disruptions Continue to Burden Working Parents,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Aug. 9, 2021, https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2021/august/child-care-school-disruptions-burden-working-parents.

- Pugel, “Child Care in Kentucky Is Crucial and in Dire Need of Public Investment.”

- KyPolicy analysis of PA-264 reports from the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services.

- Jason Bailey, “Expansion of the Child Tax Credit Is a Landmark Victory in the Fight Against Child Poverty,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, July 23, 2021, https://kypolicy.org/expansion-child-tax-credit-landmark-victory-against-child-poverty-dont-let-it-expire/.

- Samantha Waxman and Iris Hinh, “States Should Create and Expand Child Tax Credits,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 22, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/states-should-create-and-expand-child-tax-credits.

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Policy Basics: State Earned Income Tax Credits,” Oct. 13, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-earned-income-tax-credits.

- David Cooper, Sebastian Martinez Hickey and Ben Zipperer, “The Value of the Minimum Wage Is at its Lowest Point in 66 Years,” Economic Policy Institute, July 14, 2022, https://www.epi.org/blog/the-value-of-the-federal-minimum-wage-is-at-its-lowest-point-in-66-years/.

- Sylvia Allegretto and Dave Cooper, “Twenty-Three Years and Still Waiting for Change,” Economic Policy Institute, July 10, 2014, https://www.epi.org/publication/waiting-for-change-tipped-minimum-wage/.

- 803 KAR 1.090.

- Commonwealth Council on Developmental Disabilities, “Legislative Priorities 2020-2021 Policy Statements: Subminimum Wage,” 2020, https://ccdd.ky.gov/Documents/SMW.pdf.

Adrian Mojica, “Tennessee Law No Longer Allows for Subminimum Wage for Disabled Workers,” News Channel 9, April 21, 2022, https://newschannel9.com/news/local/tennessee-law-no-longer-allows-for-subminimum-wage-for-disabled-workers. - Dave Cooper, Zane Mokhiber and Ben Zipperer, “Raising the Federal Minimum Wage to $15 by 2025 Would Lift the Pay of 32 Million Workers,” Economic Policy Institute, March 9, 2021, https://www.epi.org/publication/raising-the-federal-minimum-wage-to-15-by-2025-would-lift-the-pay-of-32-million-workers/.

- U.S. Department of Labor, “National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in the United States, March 2021,” Sept. 2021, https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2021/employee-benefits-in-the-united-states-march-2021.pdf.

- Katharine Marshall and Rich Glass, “Roundup: State Accrued Paid Leave Mandates,” Mercer, April 29, 2022, https://www.mercer.com/our-thinking/law-and-policy-group/roundup-state-accrued-paid-leave-mandates.html.

Drew Desilver, “As Coronavirus Spreads, Which U.S. Workers Have Paid Sick Leave – and Which Don’t?,” Pew Research Center, March 12, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/12/as-coronavirus-spreads-which-u-s-workers-have-paid-sick-leave-and-which-dont/. - Institute for Women’s Policy Research and Impaq International, “Paid Leave and Employment Stability of First-Time Mothers,” Jan, 2017, https://t.co/XoNmhqiMr9.

- Katherine Guyot and Richard Reeves, “Unpredictable Work Hours and Volatile Incomes Are Long-Term Risks for American Workers,” Brookings, Aug. 18, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/08/18/unpredictable-work-hours-and-volatile-incomes-are-long-term-risks-for-american-workers/.

- Bridget Ansel, “The Pitfalls of Just-In-Time Scheduling,” Washington Center for Equitable Growth, Jan. 27, 2015, https://equitablegrowth.org/pitfalls-just-time-scheduling/.

- Katherine Guyot and Richard Reeves, “Unpredictable Work Hours and Volatile Incomes Are Long-Term Risks for American Workers,” Aug. 18, 2020.

Author calculations of Current Employment Statistics data for Kentucky, July 2022. - National Women’s Law Center, “State and Local Laws Advancing Fair Work Schedules,” Oct. 2019, https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Fair-Schedules-Factsheet-v2.pdf.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Nonunion workers had weekly earnings 81 percent of union members in 2019,” Feb. 28, 2020, https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2020/nonunion-workers-had-weekly-earnings-81-percent-of-union-members-in-2019.htm.

Hayley Brown, “The Union Advantage for Young Workers: Higher Wages and More Benefits,” The Center for Economic and Policy Research, Sept. 1, 2022, https://cepr.net/the-union-advantage-for-young-workers-higher-wages-and-more-benefits/. - Celine McNcholas et. al., “Why Unions Are Good for Workers — Especially in a Crisis Like COVID-19,” Economic Policy Institute, Aug. 25, 2020, https://www.epi.org/publication/why-unions-are-good-for-workers-especially-in-a-crisis-like-covid-19-12-policies-that-would-boost-worker-rights-safety-and-wages/.

- Dustin Pugel and Pam Thomas, “Personnel Cabinet Recommends Improving Compensation to Stave off State Workforce Crisis,” July 13, 2022.

Population estimates for Kentucky were 3,722,328 in 1991 and 4,509,394 in 2021 according to the Kentucky State Data Center, http://ksdc.louisville.edu/data-downloads/estimates/. - Jeffrey H. Keefe, “Public Versus Private Employee Costs in Kentucky: Comparing Apples to Apples,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, July 18, 2012, https://kypolicy.org/public-versus-private-employee-costs-kentucky-comparing-apples-apples/.

- Kentucky Personnel Cabinet, “Classification and Compensation Report,” July 6, 2022, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/39/20710/070622-3-ExBrClassCompRptJul22.pdf.

- Pugel and Thomas, “A Decade Without Raises.”

- Ashley Spalding, “Most Kentucky Teachers and School Staff Start Year Without Meaningful Raises,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Aug. 10, 2022, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-teachers-and-staff-start-year-without-meaningful-raises/.