The economy as a whole has been slowly improving and Kentucky’s unemployment rate has fallen from 10.9 percent in June 2009 to 4.8 percent now — the lowest rate since 2001. While the low unemployment rate suggests an economy almost fully recovered, another measure of employment shows Kentucky still has a ways to go.

The unemployment rate only counts people who have sought work in the last four weeks – not the individuals who, because of the depth of the job losses in the Great Recession and a slow and regionally uneven recovery, have become discouraged and stopped looking for work. Since those “missing workers” aren’t counted, the unemployment rate paints an incomplete picture of the strength of the economy.

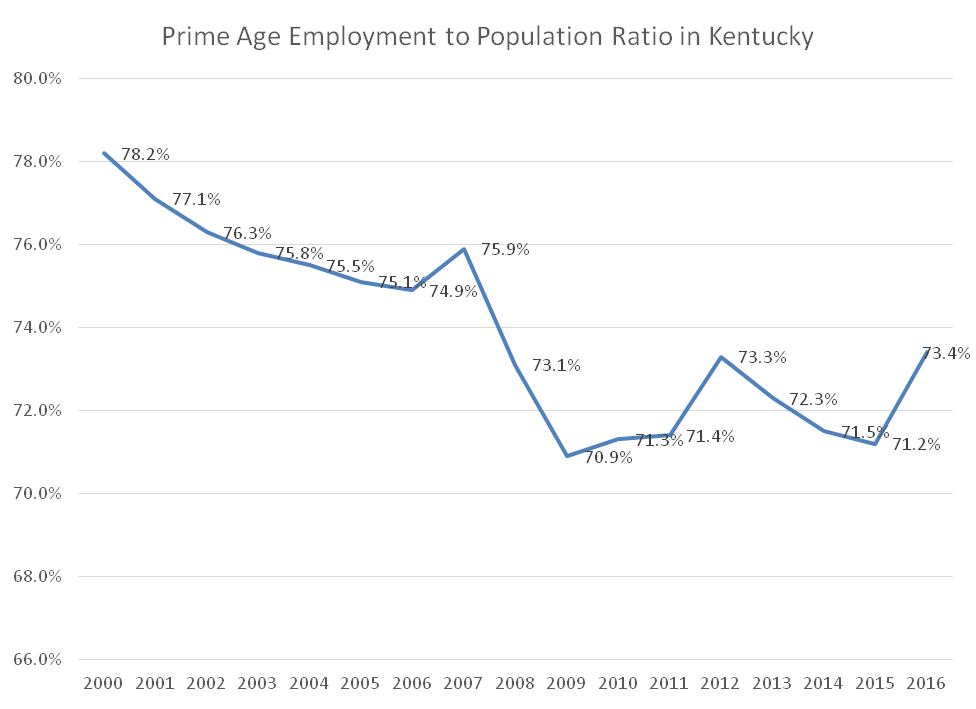

A different measure, the employment to population ratio, simply looks at the share of people with a job. By focusing on the percentage of Kentuckians employed who are of prime working age (ages 25 to 54), we can get a better sense of where the job recovery stands.

In 2016, 73.4 percent of prime age Kentuckians were employed, as shown in the graph below. That is an improvement from recent years, but still below the 75.9 percent reached in 2007 and far below the 78.2 percent in 2000.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data.

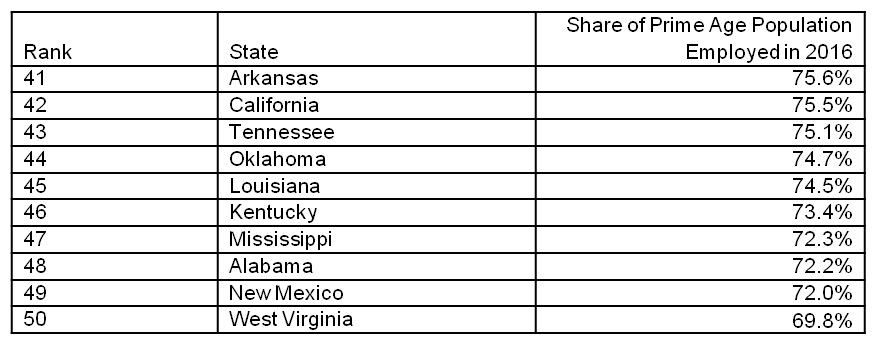

To put that gap in context: if the same share of prime age workers was employed in 2016 as in 2000, 80,000 more Kentuckians would have a job. In a typical month, Kentucky adds only about 2,000 jobs, so a jobs gap of 80,000 people is large. The state’s share of prime age population employed is the 5th worst among states, as seen in the table below, and the national average is 4.5 percentage points higher (77.9%).

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data.

Although some are quick to blame individuals’ moral failings as the cause for unemployment, the vast majority of Kentuckians are willing to work when more jobs are available, as is shown when the economy is stronger. An overall shortage of jobs in a still-recovering economy is the primary reason the ratio is still depressed. The regionally lopsided nature of the economic recovery is part of the problem, with job growth strong in more urbanized areas like central Kentucky and weak in parts of rural and eastern Kentucky. Two strategies that could create more jobs today are expanded federal investment in infrastructure and targeted job creation in distressed communities through subsidized employment programs.

Besides a lack of jobs, individuals can be unemployed because they are pursuing education, taking care of children or family members, or dealing with health problems. But it can also be because there are barriers to getting and staying employed. That can include inability to afford child care and transportation, especially with so many jobs being low wage; not enough income supports like an Earned Income Tax Credit; a criminal record that makes it difficult to find employment; and a lack of affordable access to higher education and training aligned with available jobs.

Through better policies, we can make more jobs available and increase the number of Kentuckians who can access them. But we also need to recognize what won’t work or will make the job situation worse. Kentucky is now a Right to Work state, but there is no evidence that means stronger job growth (most of the states in the table above are RTW). Repealing the Affordable Care Act will eliminate an estimated 56,000 jobs in Kentucky. And tax “reform” that is really about cutting taxes for corporations and high-income individuals won’t spur growth but cut revenue needed for the work-supporting investments described above, as states like Kansas have learned the hard way.