The federal government provided $1.6 billion in Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) monies to the state of Kentucky as part of the CARES Act that passed Congress on March 27th. As of September 9th, the state had spent or committed 52% of those monies, leaving a balance of $769 million.[1] Given doubt about additional aid from Congress in 2020, it is critical that Kentucky makes careful choices about allocating these scarce remaining dollars. The main priorities must be to: 1) combat the virus; 2) meet the needs of the most vulnerable Kentuckians facing unprecedented hardship; and 3) do what’s possible to protect critical public services from harmful budget cuts. The focus of these limited dollars should not be on an expensive and poorly targeted unemployment business tax break.

CRF monies can be used to respond to the pandemic, but are limited

The CARES Act lays out how states are allowed to allocate CRF funds. The monies may be used to cover costs that: 1) are necessary expenditures incurred due to the COVID-19 public health emergency; 2) were not accounted for in public budgets approved before the passage of the CARES Act; and 3) are incurred between March 1st and December 30th, 2020.

In guidance, the Treasury Department defines COVID-19 necessary expenditures as “actions taken to respond to the public health emergency.”[2] That includes “addressing medical or public health needs, as well as expenditures incurred to respond to the second-order effects of the emergency, such as by providing economic support to those suffering from employment or business interruptions due to COVID-19-related business closures.”

Examples of specific potential uses identified by Treasury include the cost of medical expenses like testing and treatment; public health expenses such as personal protective equipment (PPE) and tracing and quarantining; expenses due to compliance with public health measures such as distance learning at schools, sanitation and social distancing at prisons and jails, and meal delivery for senior citizens; and economic support. The guidance makes clear that CRF dollars cannot be used to replace tax revenue shortfalls caused by the recession. However, the monies can be used for “payroll expenses for public safety, public health, healthcare, human services and similar employees whose services are substantially dedicated to mitigating or responding to the COVID-19 public health emergency.”

The severity of the pandemic, depth of the resulting recession and restrictions on CRF spending mean there are many needs across the commonwealth that far outstrip the funds available through the CRF. States desperately need additional dollars to deal with budget shortfalls and fully address the crisis, but Congress is currently at a standstill on that issue and an additional round of aid is doubtful for the remainder of 2020. Given limited dollars and tremendous needs, the state must carefully prioritize the use of remaining CRF monies.

Funds should address immediate crises, including the need to combat COVID-19 and help the most vulnerable Kentuckians harmed by the recession and closures

At the top of the priority list must continue to be expenses involved in directly fighting the ongoing public health crisis of COVID-19. The more we contain the pandemic, the more lives will be saved and the better our economy will fare over time.

To date, the state has spent $91 million of CRF money directly on PPE, medical supplies, testing and emergency management costs.[3] It has also provided $159 million to the Department of Public Health to support local health departments; fund contact tracing; provide testing and support for long-term care facilities; and conduct a communications campaign to support mask wearing. And the state has provided local governments with $301.5 million to reimburse them for expenses related to COVID-19, including PPE, testing and cleaning equipment, and payroll expenses of eligible employees.

As case levels remain consistently and dangerously high, the state is likely to face ongoing costs associated with fighting the virus that will require CRF monies. Additional areas of concern include more adequate testing and inspections in prisons and jails, nursing homes and other group-living quarters, and problematic workplaces like meat processing plants.[4] Adequate funds are necessary for schools and universities to ensure any in-person classes or hybrid models can be implemented safely (including proper ventilation and sufficient safety equipment) and in ways that prevent spread of the disease to students, faculty and staff. The Department of Treasury allows states to allocate up to $500 per elementary and secondary student from CRF to cover costs associated with meeting Centers for Disease Control guidelines for in-school learning and/or distance learning without requiring specific documentation.

Another top priority must be to help individuals and families facing increased hardship due to the recession and closures. According to Census data, over 40% of Kentucky adults report a loss of household employment income in the crisis; 12% say their household didn’t have enough to eat last month; and 13% of adults with children in the household say lack of affordability meant kids weren’t eating enough.[5] Approximately 1 in 4 Kentucky adults report they are behind on rent payments, and the Public Service Commission projects $150 million is needed through 2020 to prevent utility disconnections.[6]

Despite some return to work, the state’s joblessness remains at levels exceeding the worst point in the Great Recession even while temporary layoffs are becoming permanent and the economy faces new weaknesses.[7] The conditions are worse for Black Kentuckians, who because of historical, structural barriers were more likely to be laid off in the midst of the crisis and less likely to be hired back since.[8]

Kentucky has begun allocating some CRF monies toward addressing those hardships. The state has spent or reserved for future use $29 million to deal with backlogs in the state’s antiquated unemployment insurance system. Kentucky also allocated $40 million to provide $100 a week in supplemental unemployment benefits on top of the $300 a week the Trump administration is providing for a limited period of time. And the state has assigned $15 million for eviction prevention and diversion programs and $5 million for meals for senior citizens.

Yet severe hardship continues across the commonwealth, and there are many critical needs that require more CRF dollars — especially with Congress so far failing to provide more relief for individuals and families in 2020.[9] Potential uses of CRF funds to help struggling Kentuckians include:

- Provide emergency cash assistance (to supplement Team Kentucky donations, which are first-come, first serve and limited) for people facing crises, including those who receive no or inadequate unemployment benefits or face extraordinary medical, funeral or other costs. [10]

- Provide additional funding to address the hunger faced by more Kentuckians during this pandemic.[11] Potential uses include grants to the state’s network of food banks, funding to schools and non-profits providing child nutrition programs, and funds for food assistance programs for low-income university and community college students.[12]

- Provide additional funding for rental and mortgage assistance for those facing potential eviction and foreclosure, for homelessness services across the state and for help paying utility costs to the extent and in the form allowable under Treasury guidance.[13]

- Continue supplemental unemployment benefits beyond the 5-6 week period provided by the Trump and Beshear administrations, and provide emergency unemployment benefits for those whose benefits are exhausted. Without supplemental benefits, the historically high number of unemployed Kentuckians receive only $283 a week on average. In addition, if Congress fails to extend eligible weeks of benefits (as was provided in the Great Recession), starting in October a growing number of unemployed workers will be left without any unemployment support even as jobs remain extremely scarce.[14]

- Provide financial assistance for struggling childcare centers and/or to families to support childcare costs. Because of a cut in assistance in 2013, Kentucky has lost half of the 4,400 licensed childcare providers it had at that time. The remaining 2,200 centers had to close temporarily during the pandemic, and only two-thirds of them have since reopened.[15]

- Expand outreach and provide additional assistance to ensure all eligible Kentuckians are signed up for programs like Medicaid and SNAP, including support for the Beshear administration’s goal of 100% coverage for Black and Latino Kentuckians in light of health inequities demonstrated by racially disproportionate rates of COVID-19.[16]

- Support low-income and disadvantaged students lacking broadband internet access and facing higher degrees of learning loss due to closed or hybrid schools. The state has allocated $8 million thus far from the CRF for K-12 student internet connectivity.

- Provide additional funding for increased behavioral health services in schools and communities to respond to the negative impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of Kentucky adults and children.

State should do what’s possible with CRF funds to protect public services from more cuts that will weaken communities and drag the economy down further

The basic services government provides are more important than ever in a crisis. When we cut funding to schools, universities, health and human services, infrastructure, public safety and other areas in a recession, we create new problems in our communities and drag the economy down further through public sector layoffs. State services are already stretched and limited by the 20 rounds of budget cuts the state has experienced since 2008.[17]

The uses of CRF monies to shore up the budget are restricted by CARES Act rules, which Congress should have adjusted to provide greater flexibility. But the state can still use CRF dollars to cover payroll expenses for “public safety, public health, healthcare, human services and similar employees whose services are substantially dedicated to mitigating or responding to the COVID-19 public health emergency.” Funding these services through CRF monies helps support state and local budgets, and the state should use CRF monies to the extent allowable for these purposes through the December 30 deadline.

Expensive, poorly targeted business tax break should not be focus of scarce dollars needed to address crisis

Given the limited availability of CRF dollars, the state must prioritize the use of these funds to address the immediate and essential needs described above. However, one proposal that has received some attention is to dedicate up to all remaining CRF dollars to pay off the federal loan the state has taken out to pay for state unemployment insurance (UI) benefits after Kentucky’s unemployment insurance fund was depleted.[18] But using CRF monies for this purpose at the expense of more pressing needs won’t deliver effective relief, and is also premature.

State Senate leaders have proposed using some or all remaining CRF monies to pay back the $865 million the state is authorized to borrow for UI benefits (to date, the state has borrowed $393 million of that total).[19] In paying that money back now, the proposal would provide a very small tax break to businesses that is unlikely to translate into broader benefits for the commonwealth — especially compared to the impact of using these resources to address the immediate needs described above.

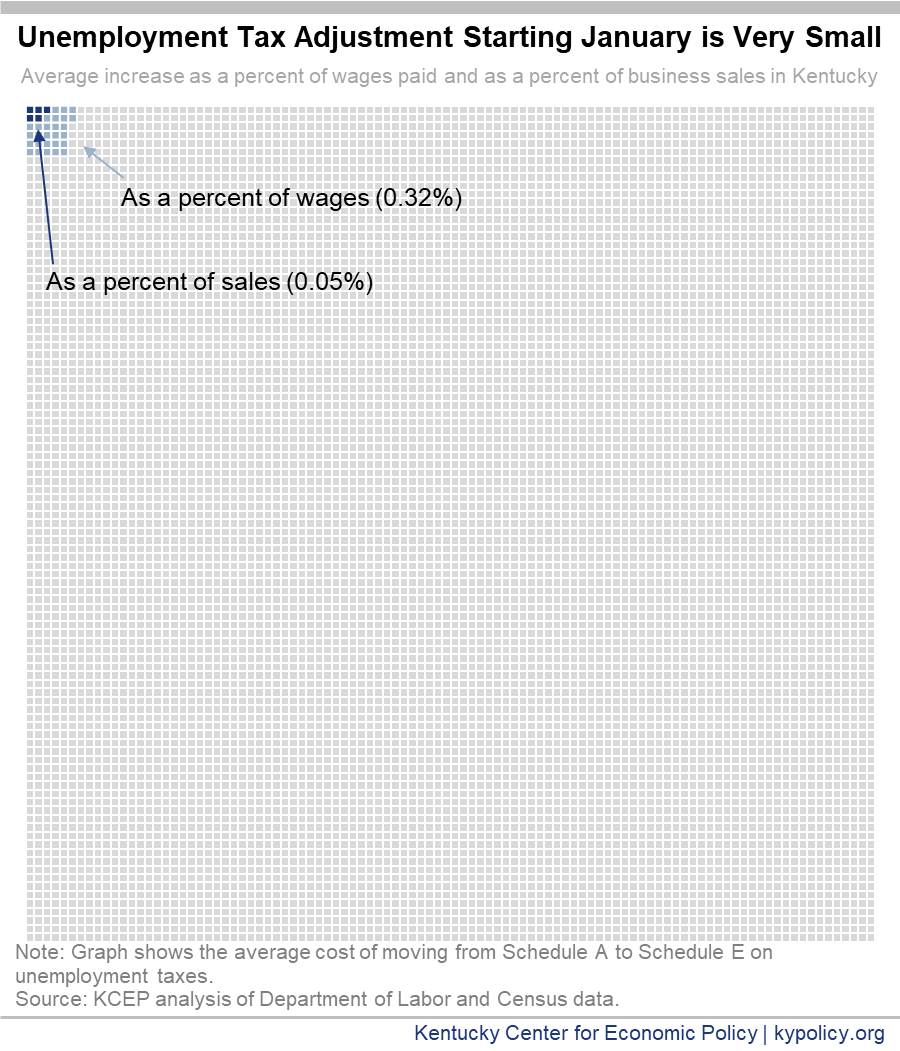

Because the state’s unemployment trust fund was used up, there is an adjustment in the unemployment tax starting in January. However, that increase adds up to only 0.32% of total wages on average and approximately 0.05% of business sales on average, as shown in the graph below.[20]

This increase is very small, and Kentucky’s average unemployment tax rate is already lower than it has ever been since 1938 when the program was created. The average rate after the adjustment will remain below where it has been approximately 82% of the time over those years.[21] Kentucky unemployment taxes are modest in part because of cuts to benefits in the past and very restrictive access for workers, and because by state law the tax only applies currently to the first $10,800 of employee wages (adjusting $300 per year until it reaches $12,000).[22] The tax applies to only 26% of total wages currently, a share that steadily declined over the decades after covering 100% of total wages when the program began in 1938. A total of 35 states apply the tax to a larger base, including 18 states in which businesses pay the tax on more than $25,000 in wages per employee. A very small tax rate adjustment to an already low tax should not be expected to have a meaningful impact on employment or business viability in the commonwealth.

It is also premature to use scarce CRF dollars to pay back the federal loan. The federal government may still take actions to address unemployment fund shortfalls, and interest payments and repayment of principal (which will require very small additional adjustments) are not due immediately. Congress suspended interest payments on the loan through the end of 2020, and the first interest payment will not be due until September of 2021.[23] A reduction in the federal unemployment tax credit for employers to begin paying back the loan principal will not begin until November of 2022.[24] Even those dates are uncertain, as additional aid on loans still may be part of future relief packages, in 2021 if not in 2020. The HEROES Act that passed the House proposes extending the interest-free period on loans by six months.[25] With 15 states having received federal loans so far, and additional ones expected to take out loans as the crisis continues, Kentucky and other states have time to advocate to Congress on potential options and terms for repayment.

Very real and pressing needs are mounting in the ongoing public health and economic COVID-19 crisis. We should not take limited dollars needed to protect health and education, safeguard families and shore up the economy in order to prepay a loan for which interest is not yet due and to provide a tiny, poorly-targeted business tax break. If there were enough relief monies to make further assistance to businesses possible, it would make more sense to provide targeted aid to small and vulnerable locally-owned businesses than an across-the-board tax break for all companies. The latter includes corporations like Amazon — one of Kentucky’s largest employers and therefore one of the biggest beneficiaries of the proposed tax break — whose profits doubled during the pandemic.[26] The state’s priority instead must be to protect lives, help Kentuckians weather this crisis and boost the economy by getting scarce dollars out where they are most needed.

[1] Letter from State Budget Director John Hicks, September 9, 2020, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/10/12842/Coronavirus%20Relief%20Fund%20response%20to%20LRC%20Office%20of%20Budget%20Review%209-9-2020.pdf. Coronavirus Relief Fund, September 4, 2020, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/10/12842/Coronavirus%20Relief%20Fund%20Summary%209-4-2020.pdf.

[2] Coronavirus Relief Fund, Guidance for State, Territorial, Local and Tribal Governments, Updated September 2, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Coronavirus-Relief-Fund-Guidance-for-State-Territorial-Local-and-Tribal-Governments.pdf. Coronavirus Relief Fund, Frequently Asked Questions, Updated as of September 2, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Coronavirus-Relief-Fund-Frequently-Asked-Questions.pdf?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery.

[3] Coronavirus Relief Fund, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/10/12842/Coronavirus%20Relief%20Fund%20Summary%209-4-2020.pdf. While this brief focuses on CRF, there are other CARES Act funding streams that partially support some of the needs mentioned.

[4] Ashley Spalding, et al., “Kentucky Must Continue Momentum Reducing Jail and Prison Population,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, September 3, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-must-continue-momentum-reducing-jail-and-prison-population/. John Cheves, “Kentucky nursing homes with the most COVID-19 deaths have this key factor in common,” Lexington Herald-Leader, September 11, 2020, https://www.kentucky.com/news/coronavirus/article245550700.html. Kentucky Equal Justice Center, et al., “Next Steps to Protect Kentucky Workers,” August 3, 2020, https://5e2859b1-1f3a-4e12-bf86-8e0de93f357b.usrfiles.com/ugd/5e2859_73a4546f4ead49e399be981fcdc4bcb2.pdf.

[5] Census Household Pulse Survey, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/household-pulse-survey/data.html. Joseph Llobrera, et al., “New Data: Millions Struggling to Eat and Pay Rent,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 23, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/new-data-millions-struggling-to-eat-and-pay-rent.

[6] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Tracking the COVID-19 Recession’s Effects on Food, Housing and Employment Hardships,” Updated September 18, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-recessions-effects-on-food-housing-and.

[7] Jason Bailey, “Continued Slow Job Growth in August, Historic Kentucky Jobs Gap Remains,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, September 18, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/continued-slow-job-growth-in-august-historic-kentucky-jobs-gap-remains/.

[8] Dustin Pugel, “Black Kentucky Workers Are More Likely to Have Been Laid Off in the Pandemic, and Less Likely to Have Been Hired Since,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, September 11, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/black-kentucky-workers-are-more-likely-to-have-been-laid-off-in-the-pandemic-and-less-likely-to-have-been-hired-since/.

[9] Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, “New Census Data on Poverty, Income, Housing Insecurity and Food Scarcity Reveal Many Kentuckians on the Brink in the Pandemic,” September 17, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/new-census-data-on-poverty-income-housing-insecurity-and-food-scarcity-reveal-many-kentuckians-on-the-brink-in-the-pandemic/. Jason Bailey, “Continued Slow Job Growth in August, Historic Kentucky Jobs Gap Remains,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, September 18, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/continued-slow-job-growth-in-august-historic-kentucky-jobs-gap-remains/. Jason Bailey, “Congress Can’t Go Home Without Passing a Strong Aid Package,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, September 18, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/congress-cant-go-home-without-passing-a-strong-aid-package/.

[10] Team Kentucky provides some financial assistance funded by individual donations. Application portal is here: https://teamkyfund.ky.gov/. Dustin Pugel, “Kentucky Response to COVID-19: Help Families with Little-to-No Income Make Ends Meet with Emergency Cash Assistance,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, March 30, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-response-to-covid-19-help-families-with-little-to-no-income-make-ends-meet-with-emergency-cash-assistance/.

[11] Jessica Klein, “More Kentuckians Are Hungry During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Congress Must Do More,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, July 17, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/more-kentuckians-are-hungry-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-congress-must-do-more/.

[12] Ashley Spalding and Jessica Klein, “More College Students Can’t Meet Their Basic Needs in the COVID-19 Pandemic, Requiring Federal and State Action,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, September 10, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/more-college-students-cant-meet-their-basic-needs-in-the-covid-19-pandemic-requiring-federal-and-state-action/.

[13] Dustin Pugel, “With Looming Expiration of Federal Aid, 1 in 4 Renting Kentuckians Might Not Make Next Month’s Rent,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, July 8, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/with-looming-expiration-of-federal-aid-1-in-4-renting-kentuckians-might-not-make-next-months-rent/. Order on Public Service Commission Case No. 2020-0085, Electronic Emergency Docket Related to the Novel Coronavirus COVID-19. In frequently asked questions, the Department of Treasury says that CRF payments cannot replace lost government revenue including utility fees that would have been paid to a government. However, “a government could provide grants to individuals facing economic hardship to allow them to pay their utility fees and thereby continue to receive essential services.” Coronavirus Relief Fund, Frequently Asked Questions, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Coronavirus-Relief-Fund-Frequently-Asked-Questions.pdf?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery.

[14] Department of Labor, Monthly Program and Financial Data for Kentucky, July 31, 2020 period, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/claimssum.asp. Chad Stone and Sharon Parrott, “Many Unemployed Workers Will Exhaust Jobless Benefits This Year If More Weeks of Benefits Aren’t in Relief Package,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 6, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/many-unemployed-workers-will-exhaust-jobless-benefits-this-year-if-more-weeks-of.

[15] Deborah Yetter, “Kentucky announces revised rules for struggling child care centers, to increase class size,” The Courier-Journal, August 31, 2020, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/education/2020/08/31/revised-rules-struggling-child-care-centers-allow-larger-classes/5656634002/.

[16] Dustin Pugel, “Covering All Uninsured Black Kentuckians Is Crucial to Achieving Universal Coverage,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, June 17, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/covering-all-uninsured-black-kentuckians-is-crucial-to-achieving-universal-coverage/.

[17] Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, “What Does Kentucky Value? A Preview of the 2020-2022 Budget of the Commonwealth,” January 2020, https://kypolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Final-online-draft.pdf. Jason Bailey, “Legislature to Pass Austere 1-Year Budget with Major Uncertainty as to Revenues,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, April 1, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/legislature-to-pass-1-year-austere-budget-with-major-uncertainty-as-to-revenues/.

[18] Letter from Senate leadership to Governor Andy Beshear, August 31, 2020, https://twitter.com/KYSenateGOP/status/1301168132409753602.

Unemployment Insurance is a joint state/federal program funded by federal and state assessments against employers. During recessions, when state trust fund balances run low, states are authorized to borrow funds from the federal government to ensure that unemployment insurance benefit payments will continue. Kentucky and 35 other states also borrowed funds during the Great Recession. Wayne Vroman, “Unemployment Insurance and the Great Recession,” Urban Institute, December 2011, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/26766/412462-Unemployment-Insurance-and-the-Great-Recession.PDF.

[19] Trust Fund Loans as of September 24, 2020, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/budget.asp.

Estimate is the additional cost of going from Schedule A to Schedule E on unemployment taxes using UI taxes as a percent of total wages reported to Department of Labor in 2019 to determine an average. Office of Unemployment Insurance, Tax Rate Schedules, https://kewes.ky.gov/Contact/contacts.aspx?strid=4. Employer Contribution Rates Calendar Year 2019, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/docs/aetr-2019.pdf. Estimate of average additional taxes as a share of sales assumes wages make up 15% of sales. According to the Economic Census, payroll costs as a share of receipts average 15% in Kentucky, including 3% in wholesale trade, 9% in retail, 10% in manufacturing, 20% in construction, 29% in accommodation and food services and 38% in healthcare and social assistance.

[21] U. S. Department of Labor, ET Financial Data Handbook 394 Report, Employment and Wage Data Report for 1938 through 2019, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/hb394.asp. Estimated Employer Contribution Rates, Calendar Year 2020, Revised September 2020, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/docs/aetr-2020.pdf.

[22] The state cut benefits in 2010 and failed to update them during the Great Recession, unlike most states did, in order to allow more workers to be eligible. Jason Bailey, “Restricted Access to Unemployment Benefits Played Role in Paying Back Loan,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, August 11, 2015, https://kypolicy.org/restricted-access-to-unemployment-benefits-played-role-in-paying-back-loan/. Adjustment of taxable wage base is at KRS 341.030.

[23] Interest payments on UI loans from the federal government must be made from sources other than the UI trust fund. Kentucky law (KRS 341.614) provides for an additional assessment against employers to make these payments if amounts included in a state fund for that purpose are insufficient. Based on the language in the statute, the maximum assessment per employee would be approximately $21 per year, and the assessment would continue until the loans are paid off. If Congress does not extend payment of interest, that added cost equals approximately 0.05% of total wages and 0.01% of total business sales, on average.

[25] HEROES Act Title by Title Summary, https://appropriations.house.gov/sites/democrats.appropriations.house.gov/files/documents/Heroes%20Act%20Summary.pdf.

[26] Alina Selyukh, “Amazon Doubles Profit to $5.2 Billion as Online Shopping Spikes,” NPR, July 30, 2020, https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/07/30/897271729/amazon-doubles-profit-to-5-8-billion-as-online-shopping-spikes