Last year, the Kentucky General Assembly passed new business subsidies and tax breaks at a cost of well over $1 billion. Especially because the state has large revenue surpluses thanks to stimulus provided by the American Rescue Plan Act, corporate special interests are pushing for even more tax breaks and giveaways this legislative session.

These subsidies are not free: They take current, and in many cases future, revenues out of the budget that could otherwise be invested in Kentucky’s public schools, human services, health and infrastructure. As the economic bump from federal stimulus fades, tax breaks will squeeze Kentucky’s investments because their cost comes off the top before the first dollar is appropriated to serve a child or a community.

In addition to proposals to cut Kentucky’s income tax rate — causing severe damage to the budget and providing a big giveaway to the wealthy — there is danger that a variety of other special interest tax subsidies may become law. Here are the breaks moving in the legislative session so far. We will update this analysis as needed.

HB 379: Tax break for data centers

HB 379 provides a big tax break to profitable tech giants like Amazon, Google and Facebook to locate “data centers” in Kentucky. These centers are nondescript warehouses filled with servers that the companies must have to process the enormous amount of data they store in the cloud. Kentucky is attractive anyway for data centers because of its low-cost electricity (a huge data center expense), reduced risk of natural hazards and central location. Tech companies must scatter these server farms across states as a technological necessity, making tax breaks unnecessary. Data centers also employ very few people.

But major tech companies and their corporate lobbyists trade on the companies’ big names to extract tax subsidies from states and localities. A 2016 study by Good Jobs First found that tax breaks to data centers were costing governments an average of $1.95 million per job. A 2021 Forbes investigation looked at just 15 data center projects that received over $800 million in tax breaks from states and localities at a cost of $1 million a job.

HB 379 provides a sales tax exemption that is broader than what is provided for any other business, even though data centers employ only a small number of employees. The bill lacks a fiscal note, but a similar version last year cost $15 million if just one data center was fully operational and one was partially operational. The program has no cap on its cost and is set to last for 30 years.

HB 447: Tax exemption for private aircraft

HB 447 would completely eliminate state and local property taxes for not-for-hire private aircraft. Aircraft already have a reduced state property tax rate of just 1.5 cents per $100 of value (the state property tax on cars, in contrast, is 45 cents per $100 or 30 times that amount). Eliminating this property tax will take $2.5 million a year from schools and local governments and $50,000 annually from the state.

Proponents claim that the tax keeps owners from parking their aircraft in Kentucky, but the Department of Revenue reports that in fact $331 million of such aircraft is sitting in the state right now. A total of 73 counties have aircraft assessed in their property tax base, including $108 million in Jefferson County and $62 million in Fayette County. Many rural counties are also home to private aircraft: $16 million in Perry County, $4 million in Martin County, $4 million in tiny Montgomery County and $17 million in Boyle County. Eliminating the tax will be a windfall to aircraft owners now paying the tax.

Proponents have made the absurd argument that many everyday people own aircraft. But the upfront cost for a small plane ranges from $8,000 to $300,000. Industry advocates stated in committee that there are 2,620 registered aircraft in Kentucky, which means that, based on their total valuation in the state, the average aircraft is worth $126,442. An aircraft owner also must pay the costs of storage, maintenance, insurance and gas and oil. Owning a plane is far out of reach of all but a few wealthy people in a state where the median wage is just $19 an hour and 1 in 7 people live in poverty.

HB 308: Investment company giveaway

HB 308 gives a huge subsidy to outside investment companies without any guarantee of job creation in Kentucky at all. This program has been peddled to state legislatures across the country by a few companies hoping to profit while claiming that rural areas will benefit. In other states where the program has been enacted, research has shown it to be problematic and ineffective.

HB 308 would cost $50 million and has no requirement that companies getting the money target it to the places that need it: investments can be made in any county except Oldham county. There is no requirement that any new jobs be projected or created with the investments. One expert said “there is no doubt this is a horrible deal for taxpayers” and that these companies’ “entire business model is to bill the taxpayers,” while in Georgia the program received a dismal audit and lawmakers are panning it as “little more than a special interest boondoggle that enriches out-of-state venture capital funds.” The General Assembly would be much better off investing that $50 million directly in the needs of rural communities ranging from clean water to broadband to child care.

HB 333: Another tax break for banks

In 2019, the Kentucky legislature completely eliminated the bank franchise tax, shifting banks over to paying the corporate income tax instead. That bill was a $56 million giveaway to banks at a time they are achieving record profits. Proponents claimed it would prevent the loss of state-chartered banks. In fact out-of-state banks were the biggest beneficiaries of the legislation, and bank consolidation has been happening in all states regardless of their tax structure since the 1990s due to interstate banking deregulation.

The banks are back with HB 333, which would unnecessarily deal them in for a profit when they loan money to community development financial institutions (CDFIs). If the state thought helping CDFIs, which provide capital to underserved populations or in poorer communities, was a top priority it could provide grants directly to CDFIs in the budget as the federal government already does. Instead, HB 333 provides a tax break of up to $20 million annually to banks for loaning or investing monies in CDFIs. Banks are already required to make investments in low-income communities under the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, and often invest in CDFIs to get credit for doing so. HB 333 would provide a windfall for what they are already doing, and waste tax dollars by unnecessarily giving private banks a profit-making role as an intermediary between the state and CDFIs.

HB 144 and HB 1: Lowering business’ unemployment taxes

HB 144 would extend for another year legislation passed last session that freezes employers’ unemployment taxes. It does that in two ways: by requiring employer taxes to be at the lowest possible rate on the state tax schedule despite the fact the trust fund is below the level that corresponds with that rate, and by again freezing the “taxable wage base,” or the portion of employee taxes that are subject to unemployment taxes, at the 2020 level. It then puts $243 million more of American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) monies into the unemployment insurance trust fund on top of the $505 million that the legislature put into the fund last year. Depositing those dollars into the fund has the effect of lowering the unemployment taxes that businesses pay in the future.

It’s important to note that Kentucky’s unemployment insurance taxes are already lower than they have ever been. The tax now applies to only 26% of wages compared to 100% when it first went into effect during the Great Depression. These tax cuts are being proposed at the same time that HB 4 passed the General Assembly, which would make severe cuts to unemployment benefits of laid-off workers, increasing hardship and making future recessions longer and more painful.

While this tax break doesn’t take dollars from the General Fund budget, HB 1 takes ARPA dollars that could otherwise be used to help those low-income Kentuckians harmed most by the pandemic and who are still facing difficulty paying for food, housing and utilities, or to provide hero pay for frontline workers, among other better uses.

HB 744: Tax break for headhunters

HB 744 is the latest proposal to use tax dollars to allegedly entice people who work remotely for out-of-state employers to move to Kentucky. Legislation with a similar goal was passed late in the session last year and would have provided a very costly tax credit of up to $15,000 over 5 years directly to people who moved to Kentucky but work remotely for an out-of-state company. Thankfully, the governor vetoed the legislation and the General Assembly did not override the veto.

HB 744 presents a new twist purportedly to achieve this same goal but by providing the tax subsidy to headhunter companies instead. The proposal provides annual payments to headhunters who “recruit” remote workers to move to Kentucky equal to 4% of the gross wages earned by everyone the headhunter recruits.1 Payments continue for a minimum of 5 years so long as the person recruited remains in Kentucky even if they change jobs, and will continue beyond 5 years unless the Department of Revenue pays the headhunter 8 times the 4% amount to get out of the deal (meaning approximately the equivalent of 13 years in which 4% of the person’s salary would go to the company).

To qualify for incentives, headhunters must apply to the Department of Revenue and must agree to spend $10 million annually on marketing, advertising, recruitment, vetting, relocating and retaining remote workers. How the headhunter spends money within these categories and how much will be spent on each person recruited is decided by them — there are no additional requirements in the legislation. HB 744 does not provide for even a minimal level of accountability and oversight. There are very few requirements for follow up and reporting, and vague standards for what the headhunter is required to do on an annual basis other than spend $10 million to continue to qualify to receive payments. There is no method for recovery of payments if a headhunter fails to comply with the requirements — in fact, it appears that the only way for payments to end is if a recruited person moves out of state or the Department of Revenue makes the “final payment” described above.

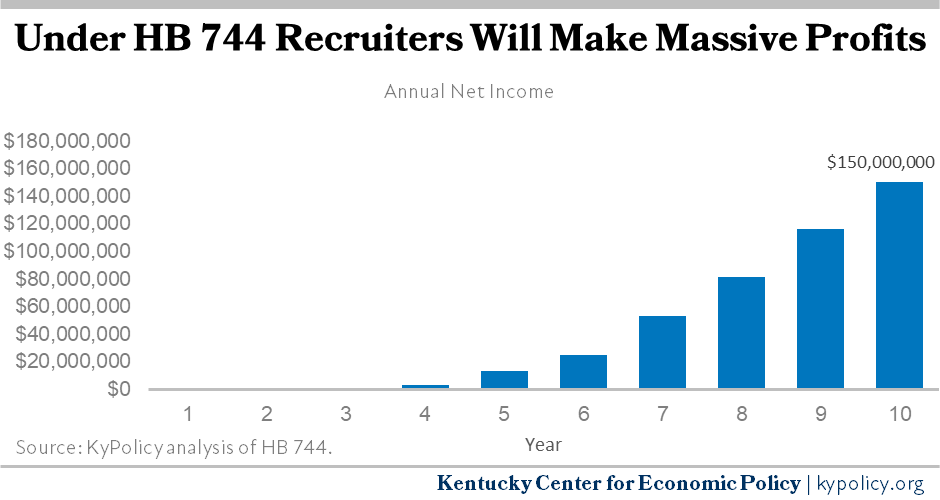

There is no fiscal note attached to HB 744, but based on projections presented by advocates of the bill in testimony before a legislative committee, after the first few years, this program will become very costly, resulting in massive profits for the headhunters. Over 10 years, the headhunters would have to spend $100 million but would receive $519 million in tax subsidies, or $150 million in net income by year 10. Even if the headhunters were half as successful as their presentation suggested, they would receive $260 million in tax subsidies over 10 years from an outlay of only $100 million.

It is important to note that approximately 40,000 tax filers move to Kentucky every year already. The headhunters could get credit for “recruiting” thousands of remote workers every year simply by paying the moving expenses of remote workers who were coming to Kentucky anyway.

- The proposed program appears to be patterned after the wage assessment used in several of Kentucky’s economic development programs that are overseen by the Cabinet for Economic Development. Those programs permit qualifying employers to impose a wage assessment of up to 4% which they then offset against income taxes withheld from employees hired as a result of the project — in this manner, the employee gets credit for having paid the taxes, and the employer retains the withheld money that would otherwise be remitted as part of the incentive package. This concept simply doesn’t work in HB 744 because the employer is not a part of the transaction — the 4% is based on the employee wages, but the payment goes to the third party headhunter and is not retained by the employer. In fact, as currently worded, it is possible that the employer could interpret the law as allowing them to retain rather than remit 4% of the amount withheld from employees, and then on top of that the Department of Revenue is directed to make quarterly payments to the headhunter (purportedly from taxes remitted on behalf of the recruited employee), resulting in a loss of tax dollars that is even larger.