The pension bill that passed the General Assembly last week, House Bill 358, reduces retirement security for future employees and jeopardizes pensions for thousands of current workers and retirees at quasi-governmental organizations like regional universities and community mental health centers. It will also shift costs to the state at the same time the General Assembly weakened its own ability to make those contributions by passing expensive new tax cuts this session.

Manufactured crisis forced decision about quasis

It is important to remember why the contribution rate for quasi-governmental organizations in the Kentucky Employees Retirement System (KERS) non-hazardous pension plan was set to rise from 49 percent of employees’ pay to 83 percent this summer. In 2016, the governor expanded the size of the Kentucky Retirement Systems board, adding members without the statutory authority to do so (which the General Assembly later changed the law to affirm). The new board then proceeded to make a sudden drop in the actuarial assumptions of the plan.

These changes were about 10 times greater than a responsible level of adjustment pension plans typically make in a single year. The long time horizon of pensions (benefits are owed in small increments over 50+ years) allows any changes to be made gradually.

That decision forced contribution requirements to spike, but the quasi-governmental organizations lacked the resources to make those payments. The General Assembly gave them a year of relief in the enacted 2018 budget, but that set up a crisis in 2019 with many quasis warning of insolvency if the relief was not extended.

Bill ends pensions for new employees and jeopardizes them for current workers and retirees

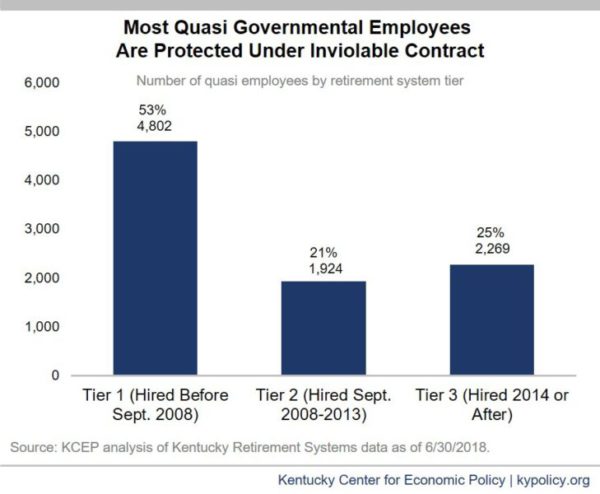

As the price of extending that relief, the General Assembly cut retirement security for workers. First, quasi-governmental organizations that cannot make the new, higher payments must leave the retirement system. Their future workers are required to receive 401k-style defined contribution (DC) plans rather than pensions. In addition, employees hired since 2014—who currently receive a hybrid cash balance retirement plan—have their benefit under that system frozen and are moved into DC plans. Approximately 2,269 employees fall into that category (known as Tier 3), as shown in the graph below.

Receiving a DC plan rather than a DB plan will put these workers in a tiny minority among public employees; only 2 percent nationwide are in DC plans rather than a form of defined benefit pensions, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. These workers will receive a lower benefit for the same price; it costs 42 to 93 percent more to provide the same benefit through a DC plan due to inefficiencies.

Receiving a DC plan rather than a DB plan will put these workers in a tiny minority among public employees; only 2 percent nationwide are in DC plans rather than a form of defined benefit pensions, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. These workers will receive a lower benefit for the same price; it costs 42 to 93 percent more to provide the same benefit through a DC plan due to inefficiencies.

In addition, current Tier 1 and Tier 2 employees are at risk of having their benefits frozen and retirees are at risk of having their pensions cut off. If a quasi-governmental organization is more than 30 days behind in making payments on its remaining liabilities after leaving the system (assuming quasis choose a payment plan option), current workers’ benefits can be frozen and retirees’ checks can be suspended. That would mean a massive benefit loss for up to 6,726 current Tier 1 and Tier 2 workers and thousands of retirees. These changes clearly are at odds with the inviolable contract. But the bill creates an institutional incentive for quasi-governmental organizations to fail to make payments because their liabilities would be lower.

Forces additional state contributions and creates difficult payment schedule for quasis

By providing terms that offer relief to quasis, HB 358 will require the state to come up with $1.04 billion more in contributions over the next 23 years, according to the actuary (who made the calculations assuming the quasis take the option to pay liabilities up front). However, the state’s ability to make those contributions worsened this session, as the General Assembly passed $106 million in tax cuts to banks and other special interests.

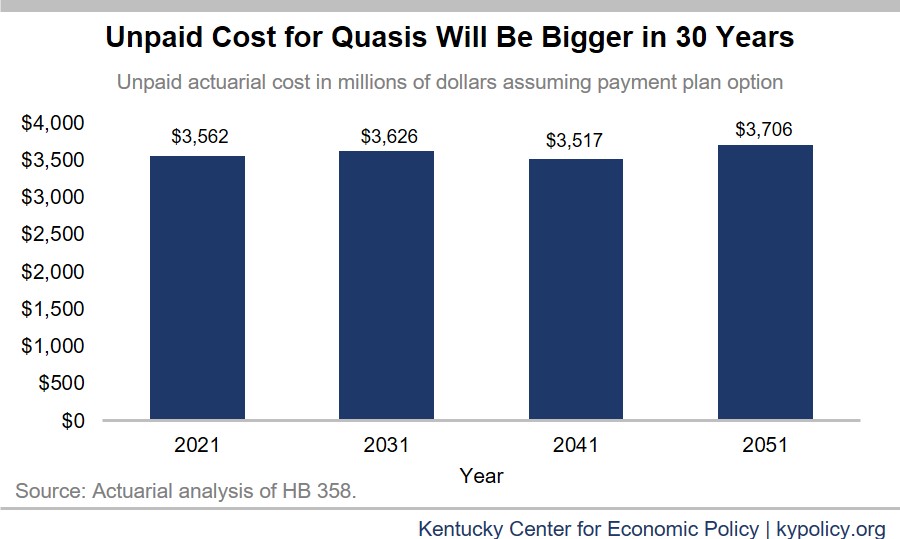

And despite short-term relief for quasis, the situation they face will still be very difficult. If they cannot finance their unfunded liabilities up-front and opt instead for the payment plan, many will not reduce their liabilities any time soon. In fact, the actuary projects that 74 of the 118 quasi agencies will still be making payments in 30 years and quasi liabilities will be bigger at that time than they are today, as shown in the graph below.

Relaxing payment schedule and raising revenue are practical ways forward

Kentucky is headed for a major crunch in the next state budget. We should be examining ways to relax the unreasonable payment schedule on pensions while fully protecting benefits. That includes questioning the wisdom of the catch-up payments we are making on retiree healthcare that most states ignore in favor of a more manageable pay-as-you-go approach, as well as the wisdom of forcing a plan that is almost totally depleted to be 100 percent funded in just 24 years using the most cautious assumptions in the country. We need more commonsense approaches to our pension challenges.

And we need to clean up the tax code to generate new revenue to help with contributions, not continuing with expensive tax breaks—like those for banks—that leave us with less.