Despite living through the longest economic expansion on record, before COVID-19, 16.3% of Kentuckians were still living below the poverty line and median state incomes were relatively stagnant, according to new 2019 Census data from the American Community Survey (ACS) released today. The numbers reflect a recovery following the Great Recession that ultimately did not reach all Kentuckians.

Since the pandemic hit, hardship has deepened and become even more widespread, particularly for Kentuckians of color and those with low incomes. New data from the Census Bureau’s ongoing Household Pulse Survey (HPS), which gauges hardship in the pandemic, paints a grim picture of the economic reality for too many Kentucky families.

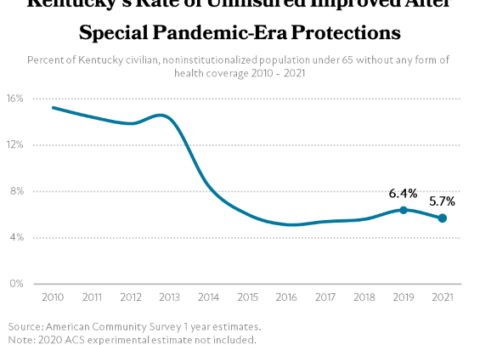

According to the new ACS data, the state’s poverty rate of 16.3% in 2019 was not a statistically significant difference from the 16.9% in 2018. The state’s poverty rate continues to be among the highest in the country and the poverty rate was 21.7% for children and 24.4% for Black Kentuckians (compared to 15.1% for white Kentuckians). At $52,295, median household income grew a little in 2019 compared to the year before (when it was an inflation-adjusted $51,157), but is at an amount below what experts consider to be a simple yet secure budget for many families. Median household income for Black Kentuckians was $39,690 compared to $54,148 for white Kentuckians. And new Census data from earlier this week shows 2019 marked the third year in a row that saw an increasing share of Kentuckians without health insurance.

“The modest progress we made on measures like median income before the pandemic wasn’t enough for Kentucky families, and since March, things have only gotten worse,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy Research Director, Ashley Spalding said. “Policy choices like lawmakers’ unwillingness to raise the minimum wage to a living wage, for example, have kept Kentuckians’ incomes stagnant for quite some time and perpetuated race and gender income gaps. Inadequate COVID-19 relief is pushing people right over the edge.”

Weekly HPS data show a worsening in hardship across Kentucky in 2020. In August, an astounding 43% of Kentucky adults reported a loss of employment income in their household since March 13. Additionally, HPS data collected this summer show that:

- Nearly one in ten Kentucky adults reported that their household sometimes or often didn’t have enough to eat in the last seven days.

- 15% of adults with children reported their kids sometimes or often didn’t eat enough in the previous week because they couldn’t afford it.

- 23% of adults who live in rental housing reported they were behind on rent.

- 42% of children in renter households in Kentucky live in a family that is not getting enough to eat and/or is behind on housing payments.

Structural barriers to economic security and well-being for Kentuckians of color – which before the pandemic were visible in indicators like higher poverty, higher uninsured rates and lower incomes – also mean that the pandemic is visiting greater hardship on them. For example, Black Kentuckians made up 16.2% of Kentucky unemployment claims in July, even though they make up only 9.8% of the workers covered by unemployment. And Black Kentuckians have been less likely to be rehired in the recovery: While there has been a 29.3% decline in white Kentuckians with unemployment claims since April, there has been only a 4.1% decline in claims from Black Kentuckians.

Amidst an ongoing public health crisis, uneven and slowing job growth is insufficient to pull families and the state’s economy back. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that, as of July, Kentucky has only recovered 52% of the jobs lost between the start of the pandemic and the low point for jobs in April; and job growth slowed down significantly in July compared to the previous two months. Nationally, temporary layoffs are becoming permanent, meaning more people who are still sidelined are not expecting to go back to their jobs.

Federal spending in a recession buffers economies from the vicious cycle of job loss leading to reduced demand. Until the pandemic is behind us and the country is in a robust recovery, federal aid is the best policy lever to pull states back from a spiral of unnecessary hardship and recession.

“Without federal aid to keep us going through the pandemic, Kentuckians will continue to struggle, especially people who were already having difficulty making ends meet because of societal barriers. Kentuckians need help paying for groceries, rent and utilities, and state and local governments need aid to keep from laying off more people and cutting vital services. In this context, much more in federal aid is the most important policy action that can be taken to alleviate poverty and bolster inadequate incomes,” Spalding said.