The calendar now marks one year since COVID-19 hit Kentucky. Over that time, the impact on human health has been enormous: over 422,000 Kentuckians have contracted the virus and nearly 6,000 have died. The coronavirus has also wreaked havoc on the economy as consumers pulled back spending and avoided public places and travel, as families dealt with extended illness and as the state put in place restrictions to save lives.

Now as more Americans get vaccinated, there is light at the end of the tunnel. But as we take note of a year under the pandemic, it’s a good time to take stock of how the economy has been harmed and make clear what ground needs to be made up. New data shows slight improvement in the Kentucky economy again in February, but a pace of job growth that is too slow considering the large jobs deficit the state faces.

The recently enacted American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) will inject over $17 billion into Kentucky, providing much-needed relief that will help jump-start faster growth. Kentucky’s state government must do its part by not hindering the recovery through idling excessive monies in the state’s rainy day fund and blocking the deployment of $2.6 billion in ARPA funds intended to address hardship and prepare for recovery.

Employment growth is slow, need for jobs is still widespread

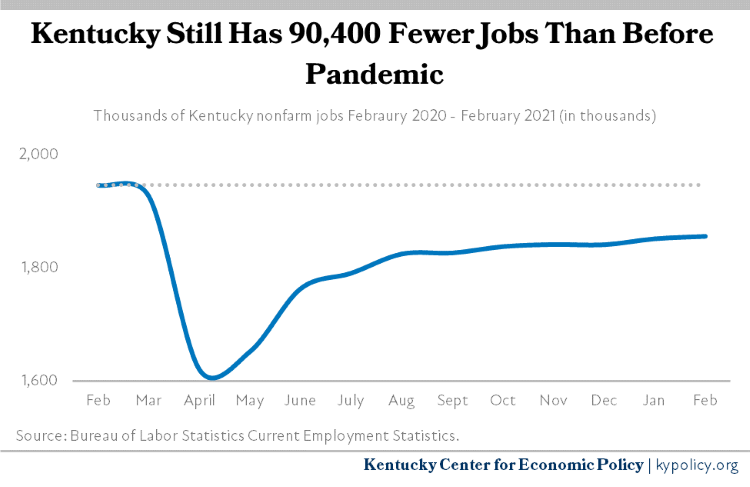

Kentucky employers added 4,300 jobs in February, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ monthly survey of businesses. But that still leaves the state with 90,400 fewer jobs in February 2021 than in February 2020, before the pandemic hit.

The pace of the job growth has slowed since an initial burst last summer. Whereas the state added an average of 51,200 jobs a month from May through August, it added only 5,200 jobs a month on average since then. The initial job growth was associated with the spending of stimulus checks and expanded unemployment benefits from the CARES Act as well as phased reopening of certain businesses. But when CARES Act aid began expiring in July and Congress passed no additional relief until the end of December, growth slowed.

Job loss and recovery have varied by industry

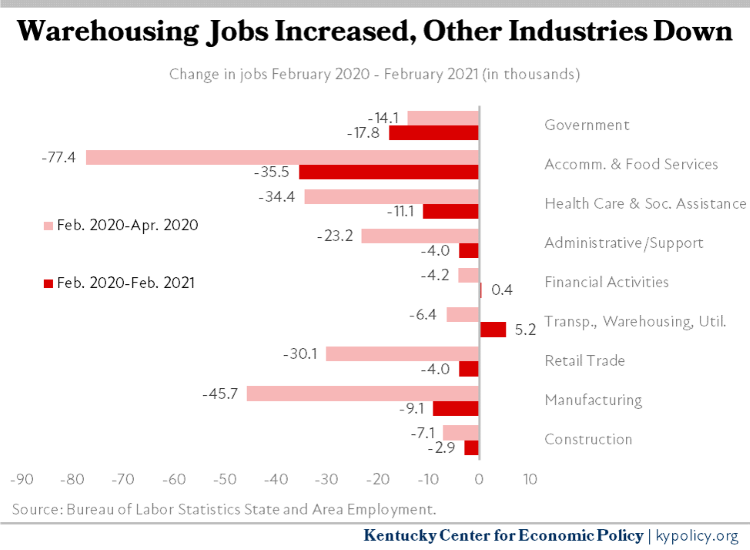

Every sector was hit hard in April 2020, as shown in the graph below. There has been improvement since then with the exception of government, where budget cuts have resulted in further decline in public sector jobs. Major gaps still persist in the sectors that have seen growth since April.

For example, the accommodation and food services sector lost 77,400 jobs by April and despite improvement still had 35,500 fewer jobs in February 2021 than the year before. Among sectors with large employment, manufacturing has 9,100 fewer jobs than a year ago, and healthcare and social assistance has 11,100 fewer jobs. Of the major industries, only the transportation, warehousing and utilities sector (think Amazon) had significantly more jobs in February 2021 compared to February 2020, with growth of 5,200 jobs.

Low-wage workers, Kentuckians of color and women are hardest hit

The disparate impacts across industries have implications for workers of different incomes and demographics. For example, Kentucky has 14.1% fewer low-wage jobs (with incomes less than $27,000 a year) than before the pandemic hit, according to Opportunity Insights. The state has 4.7% fewer middle-wage jobs ($27,000-$60,000) and 1.5% more high-wage jobs ($60,000 and above). Layoffs have hurt those who were already struggling even before the pandemic.

People of color and women are also more likely to be have been laid off due to long-standing structural barriers, a history of discrimination and the distribution of industry layoffs. Black Kentuckians made up 14.8% of those laid off and collecting unemployment benefits in January 2021, the most recent month available, while making up only 9.8% of the labor force. Women were the majority of Kentucky unemployment claimants from the summer of 2020 through November for the first time since the 1990s. That fact in part reflects disproportionate layoffs in industries like hospitality, restaurants, education, healthcare and government that have predominantly female workforces, and the distribution of care responsibilities in society.

Depressed labor force reflects lack of job opportunities, care needs

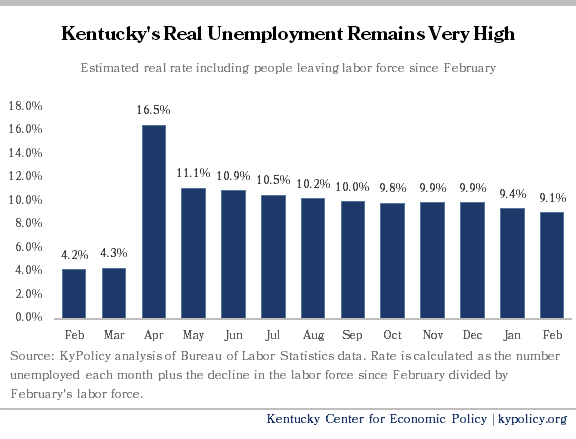

In a separate survey of households, 6,720 more Kentuckians reported being employed in February compared to January, with 2,978 fewer people reporting being unemployed. The unemployment rate ticked down slightly from 5.3% to 5.2%.

However, that rate doesn’t count the net 84,776 Kentuckians who have left the labor force during the pandemic. That number is inflated due to care responsibilities, illness and a lack of available employment opportunities in industries in which individuals work and the region of the state in which they live. Counting the reduction in the labor force since February 2020, Kentucky’s real unemployment is approximately 9.1%, as shown below.

American Rescue Plan Act is a lifeline, and state government must do its part

In a number of ways, the ARPA will help address the job gaps and provide relief to those hurting in the crisis. The combined federal spending of over $17 billion in Kentucky will circulate through the economy, creating jobs and boosting incomes.

ARPA will result in the direct employment of people in the public sector, from schools to local health departments to human services. It will result in increased consumer demand at private businesses as the newly employed and those receiving extended jobless benefits spend their money, and as Kentuckians spend $1,400 stimulus checks, child tax credit payments, food aid and more. There will be additional stimulus as people pay less out of pocket for healthcare thanks to ARPA’s premium subsidies, as restaurants and bars get targeted assistance from ARPA and as people pay rental back debt owed to landlords with ARPA assistance. And the $764 million the state will get from ARPA for child care centers will create jobs in that industry as well as allow more home caregivers to return to paid employment.

To maximize the benefit of ARPA to Kentucky, state government must do its part. Kentucky was already expecting over $600 million in one-time surplus state tax revenues thanks to stimulus from the CARES Act and prior federal aid. However, the General Assembly is proposing not to use that extra money to restore services and provide relief, but to park $743 million into the state’s rainy day fund. The General Assembly is also attempting to stop the governor’s use of the $2.6 billion from ARPA without the authorization of the General Assembly.

Yet it is clearly a downpour for people and communities across the state, and it is important that state government get these dollars out as soon as possible to provide relief and stimulate recovery. Aid should be released and prioritized to those most in need in a state with 90,000 fewer jobs than a year ago and 36% of Kentuckians reporting difficulty affording basic household expenses.

Of the ARPA monies, $2.4 billion can be used to respond to the public health emergency including the negative economic impacts on people and communities, provide “premium pay” to essential workers, protect government services harmed by lost tax revenue and/or make needed investments in water, sewer and broadband infrastructure. Another $185 million can be used to support work, education and health projects.

The faster Kentucky gets its aid and one-time money out the door to those who most need it, the less Kentuckians will suffer hardship through the remainder of the pandemic and the stronger the state’s economy will emerge from the other side.