Kentucky’s Medicaid waiver proposal frames the issue of health coverage for low-income Kentuckians largely as a problem of Medicaid participants’ lack of understanding about private insurance and failure to engage in work to obtain employer-based coverage. This approach includes several important misconceptions about who is receiving Medicaid, what’s happened to private insurance and how to best promote economic mobility in Kentucky.

Most Non-Disabled Adults With Medicaid Are Already Working

A key component of the 1115 waiver proposal is the addition of work requirements for non-disabled adults without children — making Medicaid coverage contingent upon working and/or doing community activities such as volunteer work and educational classes or programs. However, in contrast to the assumption that “able-bodied” adult Medicaid participants need to be incentivized to work, most already are. The majority of those who gained coverage through the Medicaid expansion in 2014, which increased eligibility to 138 percent of the federal poverty level or $33,534 for a family of 4, were low-wage workers — primarily employed in food service, construction, temp agencies and retail stores.

It is also important to note that there is already a “churn” in Medicaid enrollment in Kentucky, with participants regularly leaving Medicaid (i.e., due to income increases) at the same time that new members are enrolling.

Fewer Employers Offer Health Insurance and Its Costs Have Long Been Rising Faster than Wages

The Medicaid waiver proposal places emphasis on transitioning low-income workers to employer-sponsored health plans without addressing the main reasons they are not participating. The proposal initially encourages participants who have access to a workplace plan to participate — and ultimately requires enrollment in the workplace plan for these employees and their children, with the Medicaid program providing reimbursement for premiums (minus the premium the member is required to pay for Medicaid). The waiver plan also assumes lack of participation in private insurance has much to do with Medicaid members not understanding how private insurance works and focuses on educating members about private insurance. It does not acknowledge that employer-based insurance has been eroding for decades. The share of Kentucky workers with employer-based health coverage has declined from 70 percent in 1980 to 56 percent today.

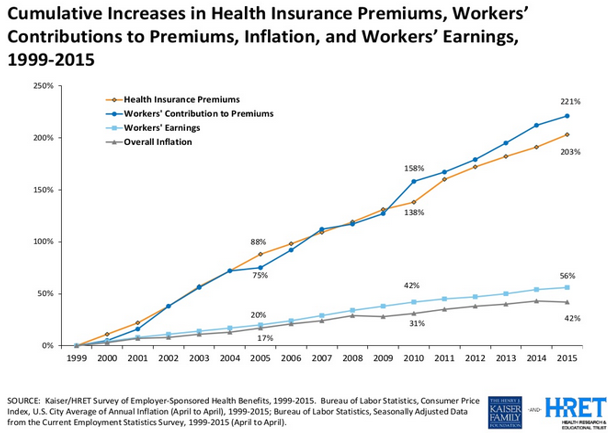

Private insurance has become more expensive, which prices many workers out of the market even when their workplace offers a plan. Nationally average premiums for family coverage have increased much faster than workers’ earnings, which overall have barely kept up with inflation (see below). Education about how private insurance works does not increase a person’s ability to afford premiums.

Source: “How Consumers’ Cost Increases Far Outpace Wage Growth,” Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, http://www.healthpopuli.com/2015/09/23/health-consumers-cost-increases-far-outpace-wage-growth/

Those Who Aren’t Working Face Significant Barriers to Employment Not Addressed in Waiver

The barriers to employment faced by Kentuckians who are not working are typically much more difficult than simply being incentivized or punished by the state’s Medicaid program. These Kentuckians find themselves looking for work in a limited job market in large parts of the state. Those with little education and/or issues in their past that prevent them from passing a criminal background check have even fewer opportunities (and the new expungement process for non-violent felonies is an important step but expensive). Other obstacles include care responsibilities for children or family members and not having access to or being able to afford reliable transportation on a low income. Meanwhile, higher education, which can improve employment prospects, is increasingly unaffordable — even at the state’s community colleges.

Measures Like Work Requirements and Premiums Are Not Successful at Improving Economic Situations for Individuals and Families

Decades of solid research show that work requirements, premiums and other punitive measures don’t move people into better jobs and can actually drive people deeper into poverty.

According to an extensive body of research, even premiums that may seem small create a barrier for health coverage for many with low-incomes. For instance, Oregon received approval in 2003 to increase the premiums it charged participants in its Medicaid waiver program and also impose a six month lock-out period for non-payment of premiums; a study found that following these changes, enrollment in the program dropped by almost half. Similar effects occurred with programs in Utah, Washington and Wisconsin. Meanwhile, those without health coverage are vulnerable to catastrophic out-of-pocket health care costs, which are the cause of the majority of personal bankruptcies in the United States.

In addition, an array of rigorous evaluations of programs tying work requirements to public assistance show this approach is not effective at promoting employment and reducing poverty. These studies found that any employment increases were modest and faded over time; stable employment for participants proved the exception rather than the norm; most with significant barriers to employment never found work; and the large majority remained poor and some became poorer.