To view KCEP’s comments for the federal comment period, click here.

To view this brief in PDF form, click here.

Kentucky is applying to modify its Medicaid program through a waiver under Section 1115 of the Social Security Act. The proposed changes will result in fewer Kentuckians covered and decrease health care access, which will ultimately harm the health status of Kentuckians and move the state backwards in its recent health care gains. And while the proposal is framed in terms of increased financial sustainability and reduced costs, it can end up costing the state more overall as it introduces new, expensive and complex administrative burdens, and limits access to the preventative care that improves health. In the end, rolling back Kentucky’s historic gains in healthcare coverage would be antithetical to the goals of the Medicaid program and the 1115 waiver process and hurt the many Kentuckians who benefit from the Medicaid program in its current form.

How far we’ve come, and what is at stake

Kentucky’s Medicaid participants include thousands of working families, veterans, pregnant women and people with disabilities, as well as hundreds of thousands of children and seniors. Current enrollees include the following:

- Children: 561,326 (39 percent) of enrollees are children.

- Working adults: The majority of Medicaid-eligible adults who gained coverage under the expansion in 2014 in Kentucky were low-wage workers 1.

- Veterans: An estimated 9,500 uninsured Kentucky veterans and 5,300 uninsured spouses of veterans became newly eligible for Medicaid under the expansion.

- Pregnant women and infants: 43.6 percent of all births in Kentucky were covered by Medicaid in 2010 (the most recent year for which data were published).

- Seniors: 90,794 of current Kentucky Medicaid enrollees are ages 65 and older.

- Disabled or requiring long-term care: 161,380 Kentucky Medicaid enrollees are eligible through disability, blindness, long-term care needs or brain injury for which they require care either in a facility or at home.

Kentucky is a national leader in its substantial reduction in the uninsured rate under the Affordable Care Act; the share of the population without insurance dropped from 20.4 percent in 2013 to 7.5 percent in 2015, according to Gallup. The Medicaid and marketplace enrollment counts show these coverage gains were driven largely by the Medicaid expansion in 2014, which increased eligibility to up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. Coverage alone is not the end goal, but it is the basis for better access to care, prevention of disease, cost-efficiency of long-term health spending and (over time) tremendous public health gains including reductions in preventable mortality.

As summarized by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Numerous studies show that Medicaid has helped make millions of Americans healthier by improving access to preventative and primary care and by protecting against (and providing care for) serious diseases. For example, expansions of Medicaid eligibility for low-income children in the late 1980s and early 1990s led to a 5.1 percent reduction in childhood deaths. Also, expansions of Medicaid coverage for low-income pregnant women led to an 8.5 percent reduction in infant mortality and a 7.8 percent reduction in the incidence of low birth weight. 2 ” When compared to Texas in 2014, which did not expand its Medicaid program, low-income Kentuckians were more likely to take prescribed medicines; more likely to receive regular care for chronic diseases such as asthma, hypertension, and depression; were more able to pay medical bills; and were less likely to use the ER as a usual source of care 3 .

In Kentucky, increased coverage has led to better access to services, including many forms of preventative care. State Medicaid data shows hundreds of thousands of people are using their new coverage for such cost-effective purposes. Comparing 2013 to 2014, the following services were funded by Medicaid:

- Cholesterol screening, 80,769 to 170,514 (up 111 percent).

- Preventative dental services, 73,739 to 159,508 (up 116 percent).

- Hemoglobin A1c tests (diabetes), 52,685 to 101,360 (up 92 percent)

- Cervical cancer screenings, 41,613 to 78,281 (up 88 percent).

- Breast cancer screenings, 24,386 to 51,292 (up 111 percent).

- Annual influenza vaccinations, 14,090 to 34,305 (up 143 percent).

- Colorectal cancer screenings, 17,164 to 35,633 (up 108 percent).

- Tobacco use counseling and interventions, 406 to 1,094 (up 169 percent).

Although each service does have a cost, the services being used by the expansion population are, for the most part, not the services that drive overall Medicaid spending. These enrollees are relatively inexpensive to cover and the coverage allows them to maintain health and continue working and caring for their families. And when a screening does indicate cancer or diabetes, it is still money well-spent 4 . Left undiagnosed or untreated, these conditions worsen and become more complicated (and expensive) to treat later on.

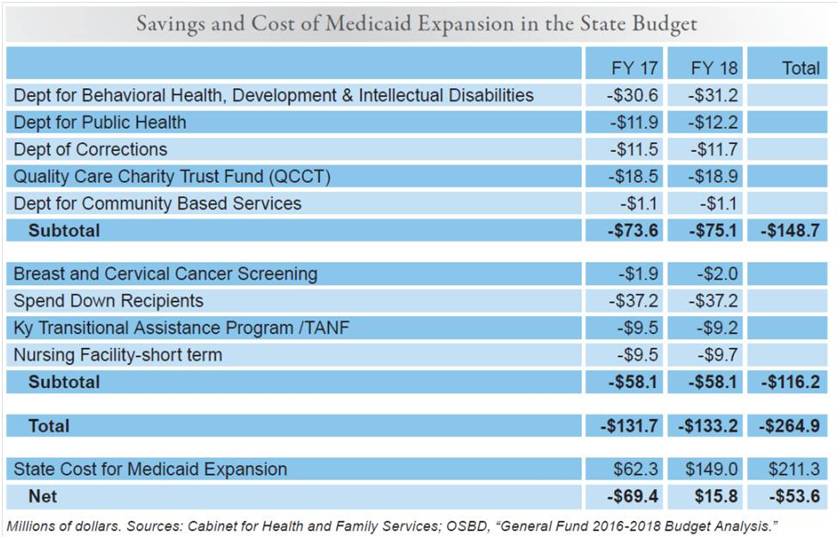

Kentucky’s current Medicaid program also has a positive impact on Kentucky’s economy, an impact that this waiver would put in jeopardy. For example, the General Fund savings Kentucky will realize because of Medicaid expansion in 2017 and 2018 from spending on public health, mental health, indigent care and other areas surpasses what the state will have to put in to match the federal investment. Even when 10 percent of the cost must be covered by the state beginning in 2020, the return on the state’s net contribution will be large after taking into account these savings, the additional tax revenue resulting from job creation due to the injection of federal dollars and the health benefits for our communities and workforce.

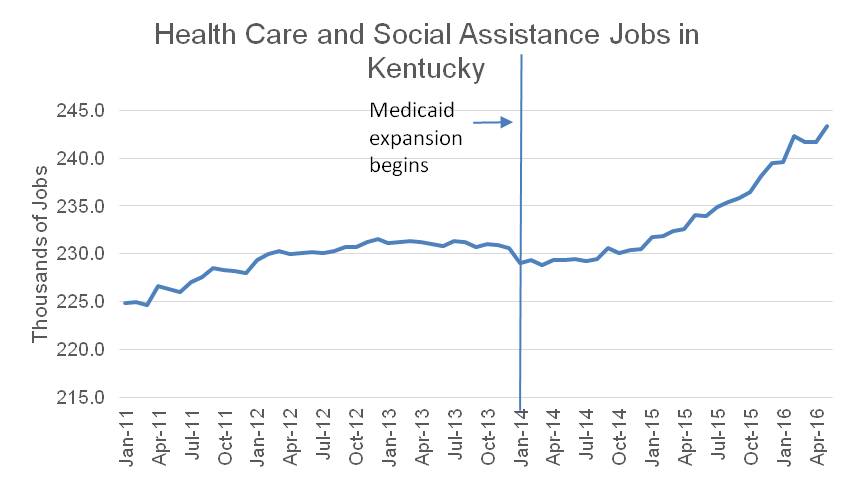

Over $2.9 billion has flowed to health care providers because of Medicaid expansion as of last October. Such an influx of funds to the healthcare system has had an impact on jobs in the state. According to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, after modest growth in health care and social assistance jobs during the first year of Medicaid expansion, growth picked up at a rapid pace in 2015. The sector grew 5.5 percent from 2014 to 2016, compared to 3.4 percent growth overall (see graph below). That growth results in income and sales tax revenue to the Commonwealth 5. Also, everyone saves when fewer people let health problems go untreated only to use expensive emergency room care later 6. Hospitals saw a reduction of $1.15 billion in uncompensated care from treating patients without health insurance during the first three quarters of coverage year 2014 when compared to the same time period a year before 7.

Source: KCEP analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

Waiver does not meet criteria set forward in law

The purpose of 1115 waivers is to provide flexibility to create and share better methods of providing health coverage and care. Waivers ultimately should result in a healthier population. They should also be rooted in evidence that the changes proposed can be made without harming the people Medicaid seeks to serve. We strongly believe that far from benefitting Kentuckians, there is evidence this waiver would be detrimental to the most vulnerable citizens in the Commonwealth. This result becomes clear when looking at the components of the proposal through the lens of the four criteria the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) use to evaluate an 1115 waiver:

- Increase and strengthen overall coverage of low-income individuals in the state.

- Increase access to, stabilize and strengthen providers and provider networks available to serve Medicaid and low-income populations in the state.

- Improve health outcomes for Medicaid and other low-income populations in the state.

- Increase the efficiency and quality of care for Medicaid and other low-income populations through initiatives to transform service delivery networks.

1. Will this waiver increase and strengthen overall coverage of low-income individuals in the state?

The waiver is projected to result in fewer people enrolled because it includes a number of measures shown to reduce coverage, including denying benefits to people who don’t pay premiums or fail to re-enroll in time and locking them out for a period of time as well as work requirements for maintaining coverage. Ample past research shows such barriers will reduce the number of people who can participate. But the purpose of 1115 Medicaid waivers is to test ways to expand coverage or otherwise improve care, not move backwards on health care access.

The waiver is designed to reduce coverage

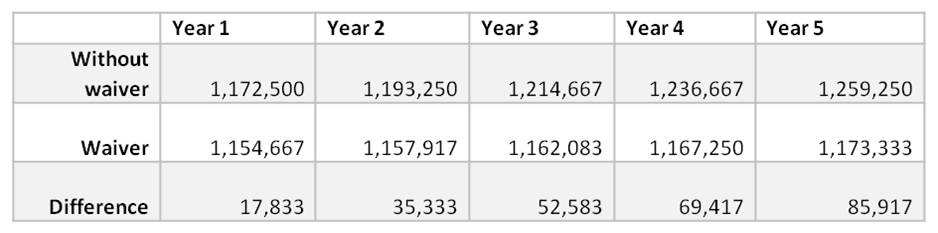

The Medicaid waiver proposal claims the changes will save $2.2 billion in federal and state money over the first 5 years of the program. But the waiver document shows those savings would occur because fewer Kentuckians are covered.

The data provided shows 17,833 fewer people will be covered by Medicaid in the first year of the demonstration compared to not having the waiver, a number that would grow to 85,917 in year 5 (data from report presents “member months,” and the table below converts that to number of full-year members by dividing by 12. The actual number of members who would lose coverage would be larger as those who lose coverage for portions of a year are taken into account).

Source: KCEP calculations from Kentucky HEALTH document.

Other elements of the waiver don’t explain the projected cost savings because the estimated cost per member, per month is actually slightly higher for the Medicaid expansion population under the waiver, though it is slightly lower for children and non-expansion adults.

Evidence does not support that the waiver will result in members’ incomes increasing such that they are no longer Medicaid eligible

The administration suggests coverage reduction will happen in part because they will move people to private insurance plans; in addition, their incomes would need to rise above 138 percent of poverty so they are no longer eligible for either regular Medicaid or premium assistance and wrap-around coverage. But it is unclear what evidence is being used to connect the assumed increase in economic well-being to the measures and requirements included in the plan.

The assumption that promoting work will somehow lead to this outcome is at odds with the research on work requirements (reviewed below) and the reality that the majority of those who have gotten coverage from the Medicaid expansion are working now; they just work in jobs where they cannot afford or are not offered coverage 8. Many workers are Medicaid recipients because a large portion of jobs pay low wages while wage growth has been stagnant, and because rising health care costs over the last few decades have led employers to shed responsibility for coverage. Whereas 70 percent of Kentucky workers had employer-based coverage in 1980, only 56 percent do today 9. Even if the minority who are not working were to suddenly gain employment — which evidence does not support would result from these requirements — it should not be expected that many would obtain jobs that lift them above 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

Experience with past safety net programs shows that work requirements do not increase well-being

In spite of a rejection of work requirements in every other state that has proposed them (including Indiana and Pennsylvania), this waiver seeks to require work or community engagement activities as both an expectation for coverage and an incentive for added benefits. However, it has been long demonstrated that work requirements in other safety net programs are not only ineffective in promoting long-term employment and wage growth, but have led to a greater likelihood of being stuck in deep poverty – at or below 50 percent of the federal poverty level 10.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ analysis of potential work requirements for Medicaid eligibility determined that such requirements would ‘unravel’ many gains from the Medicaid expansion without increasing employment:

Imposing a work requirement in Medicaid thus could undo some of the Medicaid expansion’s success in covering the uninsured… The Medicaid expansion has enabled states to provide needed care to uninsured people whose health conditions have often been a barrier to employment, including people leaving the criminal justice system who have mental illness or substance use disorders and for whom access to health care can reduce recidivism and improve employability. Connecting these vulnerable populations with needed care can improve their health, help stabilize their housing or other circumstances, and ultimately improve their ability to work. These gains would be eroded if a work requirement led to significant numbers of these individuals losing coverage and being unable to access health care that they need 11.

Also, as already mentioned, most Kentuckians getting coverage because of Medicaid expansion don’t need an incentive to work because they are already working, they are just working in low-wage jobs where they can’t afford or are not offered health insurance through their employer. In the first year of Medicaid expansion, those who gained coverage most commonly worked in restaurants and food services followed by construction, temp agencies, retail stores, building services like cleaning and janitorial services and grocery stores. These kinds of jobs usually have limited benefits, if any.

Many Kentucky workers make low wages — in fact, in 2014 30 percent made wages that would put them below the federal poverty line for a family of four. Wages are low and also have been stagnant or declining across the bottom of the wage distribution after adjusting for inflation over the last 15 years. Because the waiver creates an escalating level of premiums for those who remain Medicaid eligible, it punishes workers for the low wages and wage stagnation that are beyond their control.

In addition, jobs are lacking in significant parts of the state as Kentucky still seeks to recover from the Great Recession and as fundamental restructuring of industries like mining and manufacturing have left certain communities with far fewer jobs than are needed. Only 28 of Kentucky’s 120 counties have more people employed now than in 2007 — before the Great Recession hit — and 24 counties have seen more than a 20 percent decline in employment 12. Those decreases are not because of a sudden unwillingness to work, but because jobs were eliminated and have not been replaced. The shortage of jobs is likely to exacerbate the extent to which work requirements result in losses of coverage rather than increases in employment.

Other Kentuckians face significant barriers to better employment including a criminal record, lack of education and training, inability to afford transportation and other hurdles. Absent a more comprehensive solution to create jobs and remove barriers, measures to make health coverage contingent on certain activities will result in fewer people covered.

Premiums are a barrier to coverage

According to an extensive body of research, premiums create a barrier for health coverage for many low-income individuals. For instance, Oregon received approval in 2003 to increase the premiums it charged participants in its Medicaid waiver program and also impose a six month lock-out period for non-payment of premiums; a study found that following these changes, enrollment in the program dropped by almost half 13. Similar effects occurred with programs in Utah, Washington and Wisconsin 14. All five states that have instituted premiums for their expansion populations have seen either an increase in collectable debt among enrollees, a decrease in enrollment or at the very least an increase in churn in and out of the Medicaid program 15. Finally, since many employers don’t offer coverage, escalating premiums are an ineffective incentive for moving people off of Medicaid on to employer-sponsored health insurance. They become, in effect, a penalty for being poor – especially as they increase over time while wages in low-income jobs remain flat. Escalating premiums are also harmful for entrepreneurs whose businesses often struggle in the early years after start-up; this proposal would introduce a graduating cost to those individuals just as their businesses are getting off the ground.

Instituting a lock-out period will lead to fewer people covered

A mandatory six-month lock-out for failure to re-enroll on time or to pay premiums on time for a population already struggling with low wages will almost certainly leave people without coverage. As of April of this year, Indiana had not publicly revealed how many people had been shut out of health coverage through their lock-out period, but given the thousands who had been disenrolled for failure to pay premiums, it is likely that the ranks of uninsured adults have swelled.

Reducing some benefits is another method of reducing coverage

The waiver proposal refers to benefits such as vision and dental coverage as “enhanced benefits” that people should earn back rather than be guaranteed. This stance reflects a dangerous departure from the recognized impact that oral and vision screenings and preventative care play in maintaining health as a whole. Though modest in cost, these benefits are a critical part of Medicaid coverage.

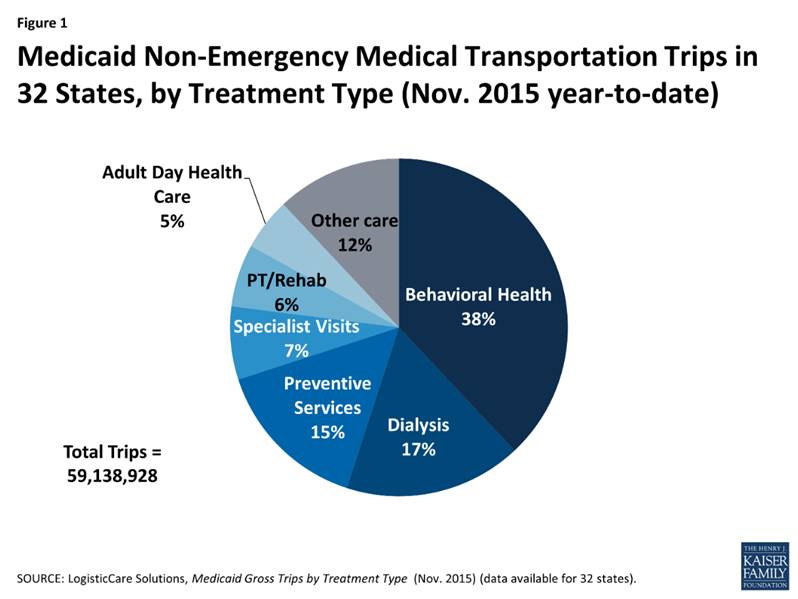

In addition, removing retroactive coverage and non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) will create added barriers to coverage and the utilization of coverage. By eliminating retroactive coverage, there is risk of individuals facing unpayable bills, which would be further aggravated by the fact that they will owe premiums. Getting to and from treatment, especially in rural parts of the state, is often a challenge, which is why NEMT is such an important component of our state’s healthcare success. In two expansion states (Nevada and New Jersey) adults who newly received coverage through Medicaid and used NEMT did so largely (40 and 30 percent respectively) to get to treatment for mental illness and substance abuse 16. Removing this benefit would limit effective coverage for many Kentuckians who have difficulty with personal transportation, and could exacerbate drug abuse and mental health problems already rampant across the Commonwealth.

2. Will it increase access to, stabilize and strengthen providers and provider networks available to serve Medicaid and low-income populations in the state?

Provider networks and providers will likely become even less available to those covered by Medicaid and low-income populations in Kentucky under this waiver. Specifically, in the case of vision and dental providers who already receive low reimbursement rates for the services they provide to Medicaid recipients, making coverage for such services contingent upon community engagement activities and healthy behavior incentives will likely reduce the number of people who use such services. It is likely that providers will no longer see it as worthwhile to continue accepting such inconsistent coverage.

Moreover, healthcare providers who serve patients that have a blend of employer-sponsored health-insurance and Medicaid, as the waiver would promote, will have to determine which insurer to bill, and create systems to be able to make those determinations. This will add more administrative overhead and inefficiency in delivering care. Some small, vulnerable providers may have to discontinue accepting Medicaid coverage because they are unable to afford the added administrative costs.

3. Will the waiver improve health outcomes for Medicaid and other low-income populations in the state?

Reductions in the number of people covered by Medicaid, disincentives for using benefits and the elimination of dental and vision coverage will not lead to healthier Kentuckians. The idea that community engagement activities, cost-sharing measures and financial or health literacy courses will result in better health outcomes is not supported by evidence. However, higher rates of coverage have been associated with better health outcomes, particularly those that can lead to early diagnosis of preventable conditions.

Dental and vision coverage are critical to wellness

Though the waiver refers to these benefits as “enhanced,” they should be viewed as necessary, basic benefits essential for health. Both of these routine services offer critical opportunities for specialized early diagnosis and preventative treatment that often cannot be offered in a primary care appointment. Such care is especially needed because Kentucky already has poor oral health and significant vision impairment, and because routine appointments with dentists and optometrists save money and sometimes lives.

The American Dental Association recommends that good oral health requires a minimum of one cleaning and check-up per year. The 2013 Kentucky Health Issues Poll found that individuals are much more likely to see a dentist if they are insured, or well off 17. Only 43 percent of uninsured Kentuckians saw a dentist in the past year, versus 70 percent of those who were insured.

Kentucky’s oral health reflects its low levels of dental care, and reducing access would only worsen these problems. A study by the Center for Health Workforce Studies shows 18:

- Kentucky ranked eighth in 2012 for adults who had a tooth extracted because of tooth decay or gum disease.

- Kentucky ranked 5th in 2012 for adults 65 years or older who had 6 or more teeth extracted for the same reasons. While this population is largely covered by Medicare, tooth decay is a long-term preventable condition that would have started much earlier.

- Similarly, for Kentuckians aged 65 or older, 23.5 percent had untreated dental cavities, 19.3 had oral pain within the last 3 months and 22.1 percent had trouble chewing food.

Low-income Kentuckians are disproportionately affected by bad oral health. For instance, 28 percent of low-income Kentuckians surveyed by the American Dental Association in 2015 said the appearance of their mouth and teeth affects their ability to interview for a job, versus 17 percent of middle and high income Kentuckians. They were also more likely to report that life was less satisfying because of a dental condition and were more likely to have problems like dry mouth, difficulty biting and chewing, pain, avoiding smiling, embarrassment, anxiety, problems sleeping, reduced social participation, difficulty with speech, difficulty doing usual activities and taking days off from work due to oral conditions.

Although poor dental health can be debilitating on its own, there are several ways in which oral health is connected to more serious health problems. Problems with oral health have been linked to diabetes, stroke, adverse pregnancy outcomes and cardiovascular disease. Dental cavities left untreated often lead to secondary infections that can become life-threatening. Routine oral exams often lead to early detection of other diseases that display symptoms in the mouth, enabling less costly diagnosis and treatment.

Medicaid’s provision of dental coverage is cost effective. Trips to the emergency room (ER) for dental-related conditions (which are covered by Medicaid) are expensive and often preventable through routine dental visits. Dental-related ER care is at least 3 times as expensive as a dental visit – $749 for non-hospitalized care 19. States that report ER visits show large numbers of patients who receive costly care for conditions that could have been prevented in a dentist’s office 20. Medicaid is the primary payer for 35 percent of all dental-related ER visits, which amounted to $540 million in 2012 21, but it only makes up 28.1 percent of non-dental-related ER visits. According to Pew, when California ended its dental care for 3.5 million low-income adults in 2009, ER use for dental pain increased 68 percent; in 2014 adult dental benefits to eligible Californians were restored.

ER visits do not typically treat the underlying dental disease, so issues like infection can reoccur, leading to costlier and repeated emergency room visits. Dental pain is also the leading gateway to opioid addiction, and doing more to prevent such pain is critical to addressing Kentucky’s drug problem.

Dental care is relatively inexpensive as a Medicaid benefit. Given current Medicaid spending per patient, utilization rates and reimbursement rates in states that offer dental benefits, the Health Policy Institute estimated that it would cost an extra 0.7 percent to 1.9 percent for the other states to begin offering that benefit 22. In 2014, the 29 states that offered some dental benefit through Medicaid collectively spent $10.1 of $327.5 billion on dental care. This means only three percent of Medicaid expenditures were spent on dental care.

Likewise, the health consequences of eliminating vision coverage for routine screenings would likely be significant. The Centers for Disease Control notes early detection, diagnosis and treatment can prevent significant loss of vision, and “people with vision loss are more likely to report depression, diabetes, hearing impairment, stroke, falls, cognitive decline and premature death. 23”

In Kentucky there are an estimated 192,060 people who are either blind or have serious difficulty seeing even when wearing glasses, according to 5 year estimates of the 2014 American Community Survey. This represents roughly 1 in 20 Kentuckians who aren’t in an institution like a nursing home. On a county level, vision impairment ranges from 1.5 percent in Gallatin county to 12.7 percent in Pike county.

Because diabetic retinopathy — or vision loss from diabetes — is a leading cause of blindness, early detection of diabetes often starts in an optometrist’s office. Other conditions like glaucoma and cataracts are also often detected early during annual vision screenings, before they become more difficult and costly to treat.

The current Medicaid vision benefit in Kentucky is modest, and only covers exams and diagnostic procedures at optometrist and ophthalmologist offices. Glasses (lenses, frames and repairs) are only covered for Kentuckians up to age 21, so most Kentucky adults are still responsible for buying their own eyewear and contacts out of pocket 24.

In the administration’s waiver proposal, beneficiaries could “earn back” vision and dental benefits by completing “specified health-related or community engagement activities.” But evaluations of similar incentive programs in Iowa and Michigan suggest few people likely would earn such incentives, leading to a big drop in the number of people with coverage 25.

Lower rates of coverage will result in poorer health outcomes

Findings from the ongoing Oregon Health Study show Medicaid beneficiaries were less likely than those without insurance to suffer from depression and more likely to be diagnosed with and treated for diabetes. Those with Medicaid were also far more likely to access preventative care such as mammograms for women 26. Another study found that 5 years after 3 states expanded Medicaid, expansion was associated with a 6.1 percent reduction in mortality 27. Recipients were also more likely to report that their health was “excellent” or “very good” and less likely to report delaying care due to costs 28.[vi] With the recent increase in screenings and other forms of preventative care in Kentucky, we can expect similar results. But as coverage is either taken away in the case of dental, vision or lock-out periods, or made less available in the case of premiums and work requirements, health outcomes will almost certainly decline.

4. Will the waiver increase the efficiency and quality of care for Medicaid and other low-income populations through initiatives to transform service delivery networks?

The waiver proposal would increase inefficiencies and add costs by creating complex new bureaucratic systems to track payments, activities and other elements that will shift dollars away from care and are likely to cost more than the revenue that is generated. While cost savings is stated as a primary purpose for submitting this waiver, it is not a sufficient criterion for an acceptable waiver on its own. Further, proposed changes would likely not even save money other than by reducing the number of people covered under the program — which could result in higher costs in the long-term as more Kentuckians are treated in the emergency room for expensive conditions that could have been managed through earlier intervention.

Added administrative costs and bureaucratic complexities will be expensive and inefficient

Creating new requirements for premiums means creating state administrative structures to bill, collect, track, answer customer questions and otherwise administer the program, including tracking expenditures against each enrollee’s income to ensure that premiums collected remain under federal caps. Also, the state must set up systems to manage two Health Savings Accounts (HSA) for each individual in the program (a deductible account and a “MyRewards” account), including tracking activities that earn credits and making payments between, into and out of the accounts. This tracking would require either expanded state government structures, or having the state contract (and oversee) the service to a third party.

Other states have examined the costs of collecting premiums in Medicaid programs and found the costs of collection typically exceed revenue collected. For example, several years ago Virginia introduced $15 monthly premiums to some families, but cancelled the program when the data showed the state was spending $1.39 to collect each $1 in premiums 29. Arizona concluded even if it charged the maximum allowed premiums, it would cost four times more to collect them than the value of the collected funds 30. Another layer of complication arises from the fact that 31.7 percent of Kentucky households with family income under $15,000 are unbanked, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation 31. This makes collecting premiums even more difficult as traditional modes of making payments will not work for a significant portion of low-income households.

Regarding HSAs, the Urban Institute’s analysis concluded, “HSAs for the poor are highly likely to be administratively inefficient. The amounts collected from individuals would be small relative to health care costs. Because there are large numbers of individuals in these programs, there would be a relatively large number of small monthly transactions. Similarly, the money that flows out of these accounts, also small amounts each time a service is used, would have to be managed…. Although these payments may lead to lower enrollment rates and more disenrollment, it is unlikely they will lead to more appropriate use of care by enrollees. 32”

Beyond collecting premiums and HSA contributions, new systems for assessing, certifying and tracking work or community engagement activities, financial literacy courses and health literacy courses will have to be created and managed. The state will then have to maintain a database that is able to affirm and record that members participated in some activity so that they can get credit in their “MyRewards” account. Then there will need to be some way of determining appropriate uses of those funds as enrollees make various health-related purchases. This will add significant bureaucratic inefficiencies and cost to the existing program.

For the premium assistance component of the waiver, yet another system will need to be created in order to track what benefits are being offered through employer-sponsored health insurance plans so the state will know what additional wrap-around services it will need to provide to satisfy all the guaranteed benefits of the Medicaid program. This will require reporting from insurance companies, a database for tracking benefit coverage for employees and ongoing monitoring for any changes that occur during open enrollment each year. It will also require that providers be knowledgeable about which program to charge for the services they perform – a patient’s employer sponsored health insurance plan, or the Managed Care Organization (MCO) offering the remainder of the benefits.

With less preventative care, costs will increase over time

Limited access to or use of preventative care is likely to add greater costs in emergency room care and in other more expensive treatment as otherwise preventable conditions worsen over time. Cutting access to early screening and detection will result in more significant health problems that go undiagnosed and untreated. Again, as was demonstrated in California, when dental benefits were cut they saw a 68 percent increase in ER usage for dental pain. As people are disenrolled without other forms of coverage, they are more likely to use care without being able to pay for it – resulting in more uncompensated care for which hospitals will seek payment.

Conclusion and recommendations

The Kentucky Center for Economic Policy seeks to improve the quality of life for all Kentuckians. We believe in policies that help create communities where everyone can thrive. To that end, we support the purposes and criteria of a Medicaid 1115 waiver as stated by CMS. That is why we are so concerned about the vast majority of the provisions in Kentucky’s proposed waiver. It is not only misaligned to the criteria of a demonstration waiver, in many cases it stands in opposition to them. Some elements of the waiver such as boosts to substance abuse treatment, chronic disease management and renegotiated contracts with MCOs are laudable, but either don’t require a demonstration waiver specifically, or don’t require waiving a part of the Social Security Act at all. We encourage the administration to continue to pursue these goals separate from the current proposal.

Work/community service requirements; premiums (including an escalation of premiums over time); reductions in coverage and benefits including loss of vision, dental, retroactive coverage and non-emergency medical transportation; lock-out periods for failure to pay premiums and for missing re-enrollment deadlines; blended employer-sponsored insurance; and complex administrative and compliance structures are real threats to the historic gains in health our state has recently experienced. For the first time in recent memory, Kentucky is heading in the right direction on health, and it would be a major mistake to go backwards now. We respectfully ask that the aforementioned features of the waiver be removed prior to its submission to the Department of Health and Human Services.

- Jason Bailey, “Many Kentucky Workers Have Gained Insurance through the Medicaid Expansion, Are at Risk If Program Is Scaled Back,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, November 10, 2015, https://kypolicy.org/many-kentucky-workers-have-gained-insurance-through-the-medicaid-expansion-are-at-risk-if-program-is-scaled-back/. ↩

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Policy Basics: Introduction to Medicaid,” June 19, 2015, http://www.cbpp.org/research/health/policy-basics-introduction-to-medicaid. ↩

- B.D. Sommers, R.J. Blendon, & E.J. Orav, “Both the ‘Private Option’ and Traditional Medicaid Expansions Improved Access to Care for Low-Income Adults,” Health Affairs, January 2016 35(1):96–105, http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/35/1/96.full?keytype=ref&siteid=healthaff&ijkey=A6hBKcGzMrX2A. ↩

- Mary Cobb, “Protecting Medicaid’s Role in Advancing a Healthy Kentucky,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, May 2016, https://kypolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Medicaid-Advancing-a-Healthy-Kentucky.pdf. ↩

- Jason Bailey, “With Medicaid Expansion, Kentucky Healthcare Job Growth Picked Up in 2015,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, March 9, 2016, https://kypolicy.org/with-medicaid-expansion-kentucky-healthcare-job-growth-picked-up-in-2015/. ↩

- Jason Bailey, “It’s Kentucky’s Lack of Coverage and Poor Health that are Unsustainable, Not Medicaid,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, March 10, 2016, https://kypolicy.org/its-kentuckys-lack-of-coverage-and-poor-health-that-are-unsustainable-not-medicaid/. ↩

- The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, “What’s at Stake in the Future of the Kentucky Medicaid Expansion?,” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, July 7, 2016, http://files.kff.org/attachment/fact-sheet-Whats-At-Stake-in-the-Future-of-the-Kentucky-Medicaid-Expansion. ↩

- Jason Bailey, “Waiver Proposal Says Cost Savings Come from Covering Fewer People,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, June 23, 2016, https://kypolicy.org/waiver-proposal-says-cost-savings-come-covering-fewer-people/. ↩

- Bailey, Kentucky’s Lack of Coverage and Poor Health that are Unsustainable, Not Medicaid.” ↩

- LaDonna Pavetti, “Work Requirements Don’t Cut Poverty,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 7, 2016, http://www.cbpp.org/blog/work-requirements-dont-cut-poverty. ↩

- Hannah Katch, “Medicaid Work Requirement Would Limit Health Care Access Without Significantly Boosting Employment,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 13, 2016, http://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-work-requirement-would-limit-health-care-access-without-significantly. ↩

- Jason Bailey, “Kentucky’s Lopsided Recovery Continues,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, May 11, 2016, https://kypolicy.org/lopsided-recovery-continues/. ↩

- Jessica Schubel & Jesse Cross-Call, “Indiana’s Medicaid Expansion Waiver Proposal Needs Significant Revision,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 17, 2014, http://www.cbpp.org/research/indianas-medicaid-expansion-waiver-proposal-needs-significant-revision. ↩

- Ashley Spalding, “Indiana Approach to Medicaid Expansion Limits Access to Needed Care,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, August 26, 2015, https://kypolicy.org/indiana-approach-to-medicaid-expansion-limits-access-to-needed-care/. ↩

- Andrea Callow, “Charging Medicaid Premiums Hurts Patients and State Budgets,” Families USA, April 2016, http://familiesusa.org/product/charging-medicaid-premiums-hurts-patients-and-state-budgets. ↩

- MaryBeth Musumeci & Robin Rudowitz, “Medicaid Non-Emergency Medical Transportation: Overview and Key Issues in Medicaid Expansion Waivers,” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, February 24, 2016, http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-non-emergency-medical-transportation-overview-and-key-issues-in-medicaid-expansion-waivers/. ↩

- Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky & Interact for Health, “Most Kentucky Adults have had Dental Visit in Past Year,” 2013 Kentucky Health Issue Poll, March 2014, http://healthy-ky.org/sites/default/files/KHIP%20Dental%20visits%20FINAL%20032114.pdf. ↩

- S. Surdu, M. Langelier, B. Baker, S. Wang, N. Harun, D. Krohl, “Oral Health in Kentucky,” Center for Health Workforce Studies, School of Public Health, SUNY Albany, February 2016, http://chws.albany.edu/archive/uploads/2016/02/Oral_Health_Kentucky_Technical_Report_2016.pdf. ↩

- Laura Ungar, “ER Visits for Dental Problems Rising,” Courier Journal, June 28, 2015, http://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/local/2015/06/24/er-visits-dental-problems-rising/29242113/. ↩

- Pew Children’s Dental Campaign, “A Costly Dental Destination: Hospital Care Means States Pay Dearly,” The Pew Center on the States, February, 2012, http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2012/01/16/a-costly-dental-destination.pdf. ↩

- Thomas Wall & Marko Vujicic, “Emergency Department Use for Dental Conditions Continues to Increase,” Health Policy Institute, April, 2015, http://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/HPIBrief_0415_2.ashx. ↩

- Cassandra Yarbrough, Marko Vujicic & Kamyar Nasseh, “Estimating the Cost of Introducing a Medicaid Adult Benefit in 22 States,” Health Policy Institute, March, 2016, http://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/HPIBrief_0316_1.ashx. ↩

- Vision Health Initiative, “Why is vision Loss a Public Health Problem?” Centers for Disease Control, September 29, 2015, http://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/basic_information/vision_loss.htm. ↩

- Dustin Pugel, “Vision Benefit Critical to Health of Kentuckians,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, July 5, 2016, https://kypolicy.org/vision-benefits-critical-health-kentuckians/. ↩

- Judith Solomon, “Medicaid Beneficiaries Would Lose Dental and Vision Care Under Kentucky Proposal,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 30, 2016, http://www.cbpp.org/blog/medicaid-beneficiaries-would-lose-dental-and-vision-care-under-kentucky-proposal. ↩

- Katherine Baicker, et. al., “The Oregon Experiment – Effects of Medicaid on Clinical Outcomes,” The New England Journal of Medicine, May 2, 2013, http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa1212321. ↩

- Benjamin D. Sommers, Katherine Baicker, & Arnold M. Epstein, “Mortality and Access to Care among Adults after State Medicaid Expansions,” New England Journal of Medicine, September 13, 2012, http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa1202099. ↩

- Ashley Spalding, “Medicaid Expansion Will Help Kentuckians Get the Care They Need and Increase Financial Security,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, May 9, 2013, http://kypolicy.us/medicaid-expansion-will-help-kentuckians-get-care-need-increase-financial-security/. ↩

-

Tricia Brooks, “Handle with Care: How Premiums Are Administered in Medicaid, CHIP and the Marketplace Matters,” Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, Center for Children and Families, December 2013, http://www.healthreformgps.org/ wp-content/uploads/Handle-with-Care-How-Premiums-AreAdministered.pdf. ↩

- Melissa Burroughs, “The High Administrative Costs of Common Medicaid Expansion Waiver Elements,” Families USA, October 20, 2015, http://familiesusa.org/blog/2015/10/high-administrativecosts-common-medicaid-expansion-waiver-elements. ↩

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, “2013 National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households,” 2014, https://www.economicinclusion.gov/surveys/2013household/documents/tabular-results/2013_banking_status_Kentucky.pdf. ↩

- Jane B. Wishner, et al., “Medicaid Expansion, the Private Option, and Personal Responsibility Requirements: the Use of Section 1115 Waivers to Implement Medicaid Expansion Under the ACA,” Urban Institute and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, May 2015, http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/ publication-pdfs/2000235-Medicaid-Expansion-The-PrivateOption-and-Personal-Responsibility-Requirements.pdf. ↩