When talk turns to state tax reform, some make the claim that Kentucky’s income tax rates are an impediment to growth and need to be reduced. But there’s nothing more destructive than income tax rate cuts to the ability of states to fairly fund public investments needed to grow the economy, as the recent experiences of North Carolina and Kansas make clear.

Proponents claim that reducing rates will encourage businesses and individuals to locate in a state, fostering economic growth. But the truth is such cuts instead cause serious harm:

- Rate reductions are a huge hit on state revenues that cannot be replaced with other sources, and research shows that the promised job growth doesn’t materialize.

- Income tax rate cuts are also a big tax cut for the rich that must be made up either through higher taxes on the poor and middle class or reduced public services.

- And income tax cuts not only fail to spur economic growth or attract investment to the state, they make growth harder by limiting investments in schools and other public services that we know make a state’s economy stronger over the long term.

Here are three big problems with reducing income tax rates:

Cutting income tax rates is hugely expensive

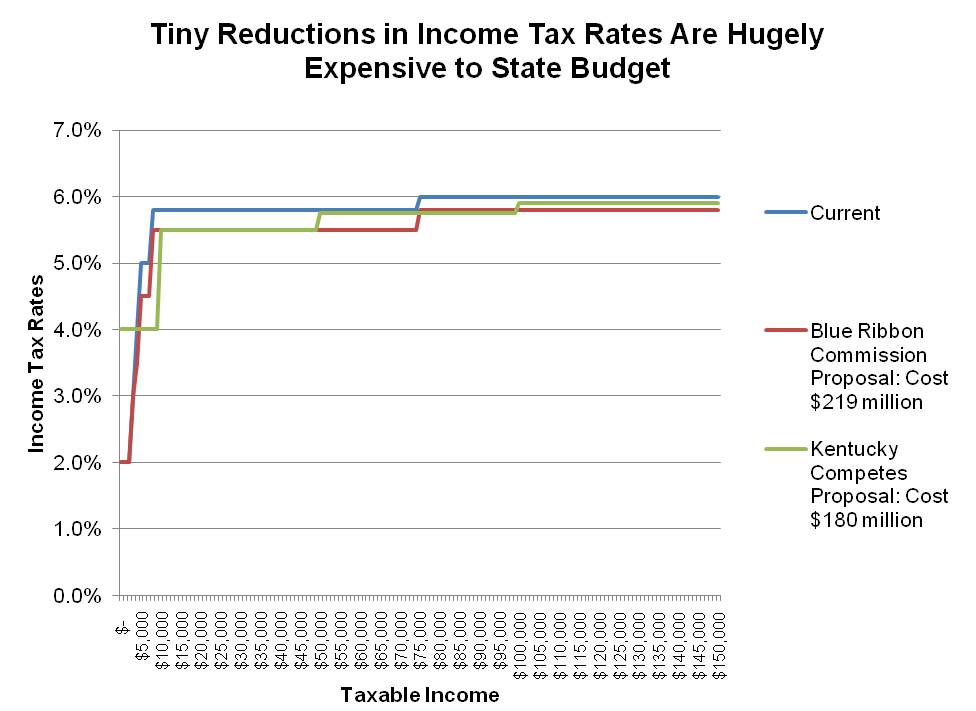

Reducing income tax rates gets very expensive, very quickly. For example, both Governor Beshear’s Blue Ribbon Tax Commission and the “Kentucky Competes” tax plan he released in the 2014 session had small cuts to individual income tax rates. The commission plan lowered the top rate from 6 percent to 5.8 percent, while the “Kentucky Competes” plan reduced the top to 5.9 percent (in both cases there were also small changes in other rates). The tiny reductions in rates can be seen in the graph below.

Source: KCEP analysis of “Kentucky Competes” and Blue Ribbon Commission documents.

Despite the fact that those proposed rate cuts were very small, they were extremely expensive. The cut in the top rate to 5.8 percent (and accompanying reductions in lower brackets) would cost $219 million, while the reduction to 5.9 percent would blow a $180 million hole in the budget. In either case, that’s about as much as the state collects from the lottery, coal severance taxes or cigarette taxes.

Cutting rates is a big tax cut to the wealthy

Such cuts also disproportionately help the rich. The income tax is a progressive tax, meaning that the wealthy pay a larger share of their income in the tax than do the poor. And when income tax rate cuts are accompanied by expansions in sales taxes to try to make up for lost revenue, the result is a tax shift from the rich to the poor and middle class.

That can be seen in the graph here and in an analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy of a bill to eliminate Kentucky’s income tax and expand the sales tax to most services, which was introduced in the 2011 Kentucky General Assembly. That bill would’ve given the richest one percent of Kentuckians an average tax cut of over $27,000 while raising taxes, on average, for the bottom 60 percent of the state’s taxpayers.

Cutting rates harms future budgets by weakening our strongest revenue source

A third big problem is that especially in a time of growing income inequality reducing reliance on income taxes in favor of sales and other taxes will mean slowing down the rate of state revenue growth. Here in Kentucky, the wealthiest one percent received nearly half of the state’s income gains since 1979, while the wages of middle- and low-income Kentuckians have been stagnant or even declining. A good portion of that income at the top is not spent but is instead saved, meaning that sales tax revenue is not generated. At the same time, the lack of wage growth for working families who spend all their earnings limits what sales tax revenue we do collect. The resulting revenue problem for states more reliant on sales taxes was recently pointed out by the credit rating agency S&P.

Within Kentucky, the effect of growing income inequality can be seen by comparing the growth of income to sales taxes. Whereas sales tax revenues have grown by 11 percent since 2007, income tax revenues have grown by 23 percent. While modernizing the sales tax to include more services will help its growth, it will never perform as well as an income tax when incomes are growing so much more rapidly at the top.

Kansas and North Carolina Are Warnings of What Not To Do

The danger from income tax rate cuts can be seen in what Kansas Governor Sam Brownback called their recent “real live experiment” in income tax rate cuts, and in the case of North Carolina.

Kansas passed tax cuts in 2012 that cut the top income tax rate from 6.45 percent to 4.9 percent (with a plan to drop it further to 3.9 percent in 2018). The law also eliminated the income taxes on profits that are passed through to owners of businesses. Brownback claimed that the cuts would be “like a shot of adrenaline in the heart of the Kansas economy.”

Since then, Kansas has lost about eight percent of its revenue, and that loss will double to 16 percent in five years if the tax cuts aren’t rolled back. The state has $803 million less this year and will have a cumulative loss of more than $5 billion by 2019. Kansas is still cutting funding to schools when most states are beginning to reinvest, and Kansas’ aid to local schools is 17 percent below pre-recession levels.

The income tax cuts provided big giveaways to those at the top. The top one percent saw an average tax cut of about $21,000, while the plan actually raised taxes on the poorest 20 percent of Kansans, on average, because of an accompanying sales tax increase. And contrary to promises, the tax cuts haven’t led to economic growth. Job growth has been slower in Kansas than the country as a whole since the cuts were passed. The state’s share of all U.S. business establishments has been falling, and its official forecast says Kansas’ economy will grow more slowly than the nation’s over the next two years.

Similarly, North Carolina passed tax cuts in 2013 that cut the top individual income tax rate from 7.75 percent to 5.8 percent (and 5.75 percent in 2015). That plan also reduced the corporate income tax rate, expanded the sales tax to include some services and eliminated the state’s Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC).

Originally expected to cost $600 million per year, the tax cuts are costing at least $200 million more because the promised economic growth from the cuts hasn’t come to pass. That led to a state revenue shortfall of $445 million in 2014. North Carolina has the second-biggest funding cut to its schools among states this year. And the tax cuts are now expected to cost North Carolina over $1 billion a year once fully implemented.

Like Kansas, the North Carolina plan is also a tax shift from the wealthy to everyone else. The plan increases taxes, on average, for the bottom 80 percent of North Carolinians while providing almost a $10,000 tax cut for those making close to $1 million. Almost two-thirds of the net tax cuts will go to the richest 1 percent of North Carolinians.

Income Tax Is a Key Tool for a Prosperous State

Political leaders shouldn’t buy the tale that individual income tax rates must be reduced to spur growth. The research on the issue is clear: states with smaller or no income taxes perform no better economically, while those states less reliant on income taxes have a harder time funding schools and other critical public services needed for long-term growth.

There are important reforms to make to income taxes—in particular the need to reduce deductions and exemptions that disproportionately benefit the wealthy. But the additional revenue from such reforms should be used to fund needed public investments, not given right back to the rich in rate cuts. Kentucky should focus its efforts on protecting and strengthening the income tax as a key tool for investments in schools and other areas that could move the state forward.