A recently released report from the state Legislative Research Commission (LRC) raises the alarm around the growing number of state inmates housed in county jails. This trend underscores the need for serious criminal justice reforms in Kentucky beyond the first step reentry measures passed in the 2017 General Assembly.

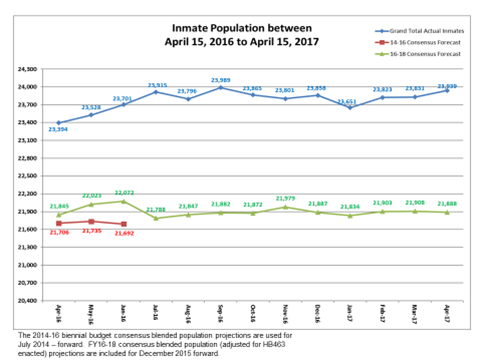

Kentucky ranked second highest in the nation for the imprisonment of state and federal inmates in local facilities as of 2014, the report shows. Close to half of the state’s inmates are now housed in county jails — 11,000 inmates as of Sept. 1, 2016, when there were around 24,000 in the entire corrections system.

Kentucky’s county jails were originally designed to house inmates that committed very low-level crimes for short periods of time. However, in 1992 the General Assembly began requiring those with Class D felonies be housed in local jails — and currently most inmates with Class D (1 to 5 year sentence) and Class C (5 to 10 year sentence) felony convictions are eligible to serve up to 5 years of their sentences in local jails. As the state’s inmate population continues to grow, local jails are becoming increasingly overcrowded. This means inmates may face worsened living conditions and serve up to five years incarcerated without access to many of the programs available in prisons that can help reduce the chances of recidivism — the return of an inmate to jail/prison after release.

Source: Kentucky Department of Corrections.

Here’s what the LRC report found:

Most of Kentucky’s County Jails Are Over Capacity

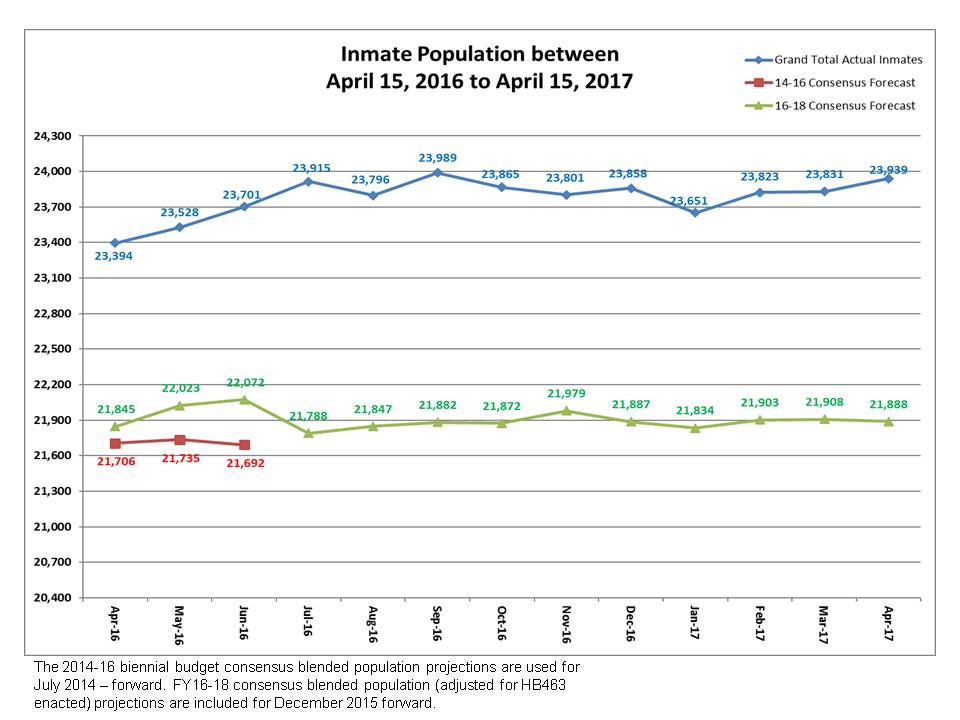

Overall, the 76 county jails that house state inmates are at 120 percent of capacity — including 6 that are at more than 160 percent. Just 7 jails are not over 100 percent capacity. As seen in the table from the report below, this has meant dorm and cell overcrowding, among other negative impacts.

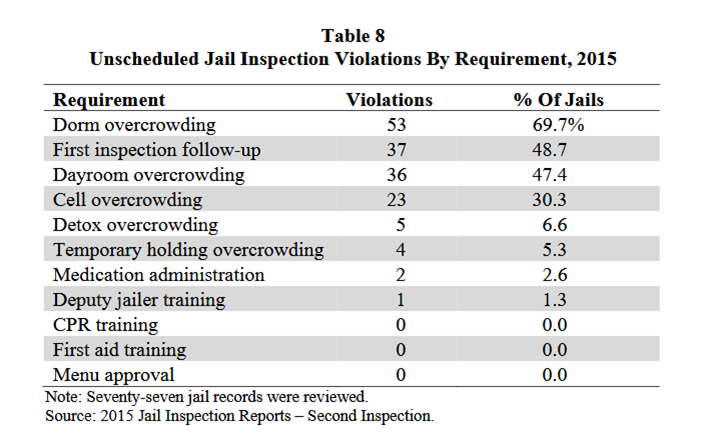

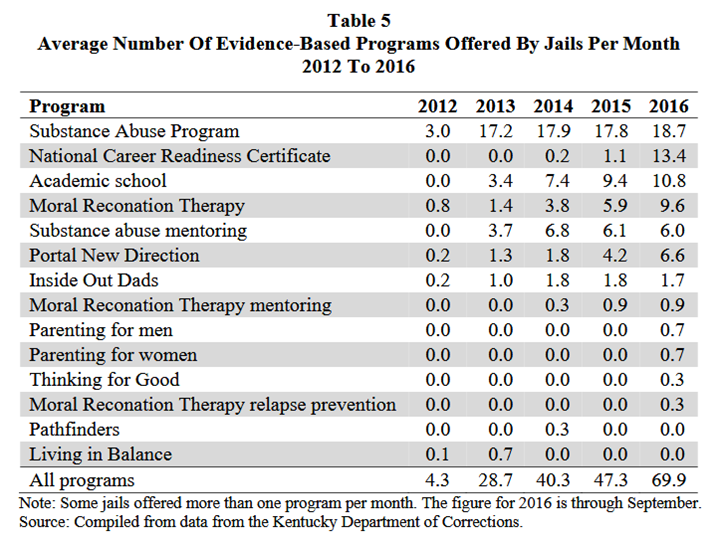

Programs That Help Reduce Recidivism Limited

Inmates with felony convictions housed in jails rather than prisons may be less likely to reenter society successfully after being released. Recidivism rates are higher for Kentucky inmates housed in county jails rather than prisons. For inmates convicted of a Class C felony, the share of inmates who recidivated within 3 years is 43.6 percent for those in county jails, compared to 40.2 percent for those in a minimum security prison and 41.4 percent for those in a medium security prison.

This difference may have to do with inmates in local jails typically having much less access to programs that help to reduce recidivism — such as substance abuse programs. Most jails do offer at least one type of program; substance abuse treatment is the most common program offered, but the report says just 25 percent of the jails provided one. The study found that female inmates sometimes had less access to programs than male inmates as there are relatively few female inmates in some jails. The table below shows that while the availability of programs in county jails has increased, programming remains minimal in these institutions.

Transferring Inmates Between Jails Has Increased

The LRC report found that transfers of inmates between jails have increased significantly in recent years — growing by 53.2 percent between January 2011 and December 2015. One reason inmates are transferred is a lack of space. The report notes that “Frequent transfers can prevent inmates from completing programs that reduce sentences or lower recidivism.”

Too Many Inmates Remain Unclassified

Inmates go through a process for receiving a security classification that can determine their eligibility for programs, work assignments and sentence credits; the classification process can also determine if an inmate requires supervision at a state prison rather than a county jail. Largely as a result of space issues in the state’s prisons and county jails, there is a large backlog of inmates awaiting security classifications. According to the LRC report, the number of inmates awaiting classification has doubled since August 2011 and is around 3,000. While some jailers report that the Department of Corrections (DOC) has suspended the classification process — which occurs at state prison classification and assessment centers — for two years due to prison overcrowding, DOC staff indicate that it has not been suspended but has slowed due to limited bed availability in state prisons.

Criminal Justice Reforms the Answer

The rise in the state inmate population in local jails is driven by continued growth in the corrections system as a whole — and the state’s lack of action on needed criminal justice reforms. More must be done to stem the tide of the rising inmate population, and reopening failed private prisons, which have been very problematic in Kentucky in the past, is not the answer.

The reentry bill that passed the 2017 Kentucky General Assembly, while positive, is expected to make only modest reductions in the state’s inmate population. Broader reforms, which were under consideration and would have had a dramatic impact, did not make it into this year’s reform package. Meanwhile other criminal justice bills that did pass will worsen the problem by increasing sentences.

In order to address these issues — including the high costs to the state — Kentucky needs to move forward with criminal justice reforms that will do more to reduce the state’s growing inmate population.