With the economy now experiencing the longest recovery on record, there is a temptation among some to overstate the strength of the labor market and even cast blame on workers if they are not currently employed. Measures like the labor force participation rate are often misused to support those claims. But a close look at this measure shows a more nuanced story about Kentucky’s economy and the makeup of who is in, and more importantly who is not in, our labor force.

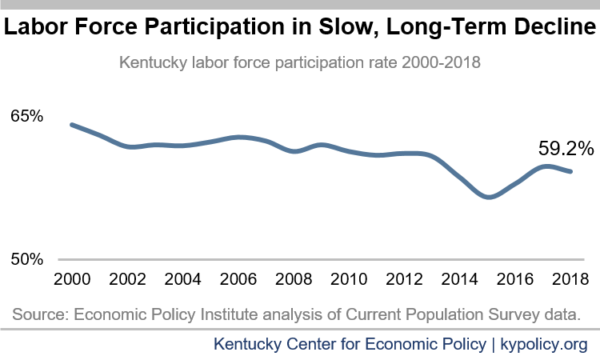

Kentucky’s labor force participation rate, as seen in the graph below, is often cited publicly as a source for concern – and even as a source of justification for policies that would make it harder for low-income Kentuckians to make ends meet, such as cuts to safety net programs. Though we have recovered from a post-recession dip in participation, we’ve snapped back to a slight, but long-term trend of decline. Last year was no exception, with the rate showing a statistically insignificant decline to 59.2% in 2018.

The details of how this rate is measured helps explain some of its decline, a trend that is not unique to Kentucky but mirrors the trajectory across the U.S. The labor force participation rate is the share of the civilian population 16 years old and above that is either employed or actively looking for work (people who are in the armed forces, incarcerated or in a nursing home are not part of the population that labor force participation measures).

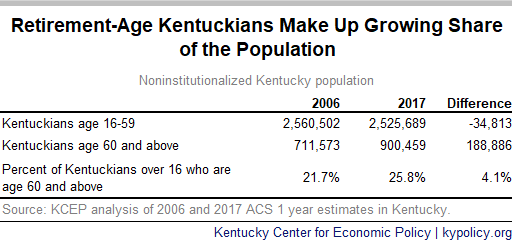

Crucially, the labor force participation rate includes retirement-age adults. The aging of the baby boomer population (those born between 1946 and 1964) into retirement has been bringing down our labor force participation rate for a number of years. In 2006 (when the first baby boomers turned 60), the share of Kentucky’s population over 16 who were retirement age was 21.7%, but by 2017 it had grown to 25.8%. Kentuckians included in the labor force participation rate under age 60 actually shrunk by 34,800, while those 60 and over grew by 189,900.

According to analysis from KentuckianaWorks of Current Population Survey data, the plurality of those outside the labor force were retired, and the rest were enrolled in school, living with a disability, could not find work or were caring for children or a loved one. These circumstances accounted for around 98% of all Kentuckians outside the labor force; only 2% of those not working or looking for work had a reason for non-participation in the labor force that could not be identified in the data.

Additionally, there are a number of economically distressed communities across the commonwealth, many in rural areas, where job opportunities are lacking. That affects the likelihood that those wanting work have actively looked in the last month. According to the same analysis from KentuckianaWorks, among Kentucky counties located in a Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), the labor force participation rate in 2017 was 65%, which was higher than the national rate. But rural Kentucky counties outside of an MSA had a labor force participation rate of 52%. Low labor force participation exists in places where jobs are few.

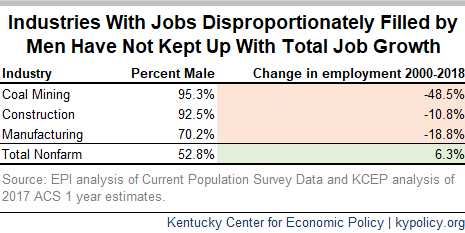

Another factor explaining the long-term decline of labor force participation is the waning of industries with jobs disproportionately filled by men that offer a decent wage without requiring a high degree of formal education. These include mining, construction and manufacturing, in which employment fell by 49%, 11% and 19% respectively even as total nonfarm employment grew by 6% since 2000.

Research suggests when these middle-skill jobs are eliminated, some displaced workers have difficulty returning to the labor force. Stagnant and low wages may be a disincentive to participate in the labor market for those who lost good paying jobs and face barriers to being hired in other industries.

Kentuckians who want to work face other barriers that stem from a lack of policies to help promote participation. These include access to job training, adequate public transportation and paid leave that allows workers to keep a job when family or health issues arise. Would-be workers also need more available and affordable child care; half of the state’s population lives in a “child care desert” where there are not enough child care centers for parents to send their children. One in six Kentucky parents report that child care issues like difficulty finding and affording care affect their employment.

One way to help overcome some of those barriers is through higher wages, but Kentucky’s median and minimum wages have stagnated while systemic racism and sexism hold back wages for people of color and women. In addition to policies that could help create new jobs where they are needed, Kentucky also needs changes that improve job quality and economic security for all workers.