Updated on Feb. 2, 2022

Fundamental to providing services like P-12 education, legal defense and child welfare is the state workforce that delivers them. Despite these workers’ critical roles, Kentucky’s state government workforce is in crisis with many agencies and departments unable to hire or retain employees. This crisis has been building for many years due to a lack of investment in the people who make state government run, and the COVID pandemic has only added stressors.

This report is available as a PDF here.

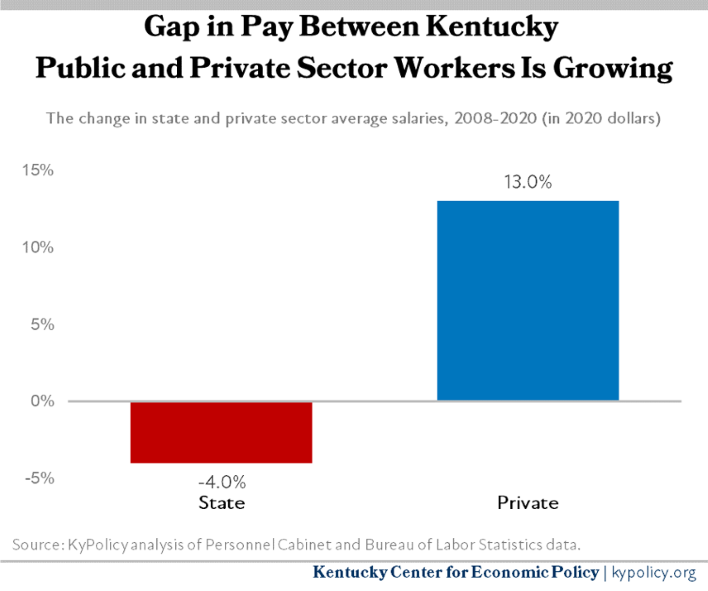

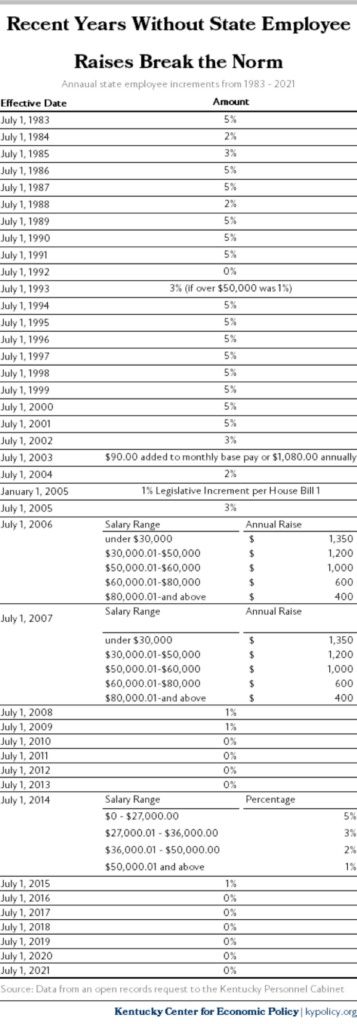

State workers have not seen a meaningful pay raise in at least a decade, leading to a wage decline of 4% on average after adjusting for inflation since 2008 compared to rising wages for private sector workers. In fact, state employees have received only 2 very modest raises in the past 12 years (see table in Appendix 1) despite a state law that requires 5% annual increments for all state employees.1 Over that same period, state employee pension and health benefits have been cut, and employees have been asked to pay more for the benefits that remain, further reducing the attractiveness of public employment. From public defenders and social workers to legislative staff and school employees, low wages, reduced benefits and unmanageable workloads have resulted in a crisis in job quality leading to high rates of turnover, inexperienced staff and staffing shortages.

This crisis is compromising Kentucky’s ability to provide critical public services, but the 2022 General Assembly’s historic opportunity to begin reinvesting through the budget because of revenue surpluses provides a way forward. The budget proposed in the House includes a 6% across-the-board raise in 2023, no raise in 2024, and additional raises for certain positions. Given the resources available, that is an insufficient step toward reinvesting in Kentucky’s state workforce, and as the budget is debated, the General Assembly must do more.2

State worker wages are left behind by private sector pay

According to the Personnel Cabinet, there were 30,837 combined executive, judicial and legislative branch state employees as of November 2021 with an average salary of $45,040 — an amount that is significantly below what is needed for a modest but secure family livelihood in Kentucky ($68,238 for a family of four in Franklin County, for example).3 It is difficult for state government to attract a quality workforce when the private sector can consistently pay more.

The last comprehensive look at public vs. private employee total compensation (wages and benefits) in Kentucky was conducted by KyPolicy in 2012. That study found that workers in Kentucky state and local government earned significantly less than comparable Kentucky workers in the private sector despite having higher levels of education. When controlling for education, age and other demographic factors, state employees earned 22.3% less in annual wages and 8.1% less in total compensation (wages and benefits) than comparable workers in the private sector.4

Since 2008, the year that state employee raises effectively stopped in Kentucky, the average state salary has fallen an inflation-adjusted 4%.5 During that same period, the average annual salary for private sector employees actually increased by an inflation-adjusted 13%.6 Also, that 2012 analysis happened before the defined benefit pension plan for state workers was ended, as described below.

Additionally, as of November 2019 there were 7,848 employees earning less than $15 per hour. This is a large share of the state workforce and includes 6,629 employees in the executive branch, 1,178 in the judicial branch and 41 in the legislative branch.7 In July 2015, then Governor Steve Beshear filed an executive order to raise the wages of Kentucky’s lowest-paid employees to a minimum of $10.10 per hour, which included over 800 state employees and cost only $1.6 million.8 This executive order was reversed in December 2015 by Governor Bevin.9 Because the minimum wage has not been increased in nearly 13 years, this means that the wage floor for state workers has also remained extremely low, pulling down the average wage substantially. In addition to the need for across-the-board raises, an increased state worker minimum wage is also very badly needed.

Turnover and attracting new workers are serious problems

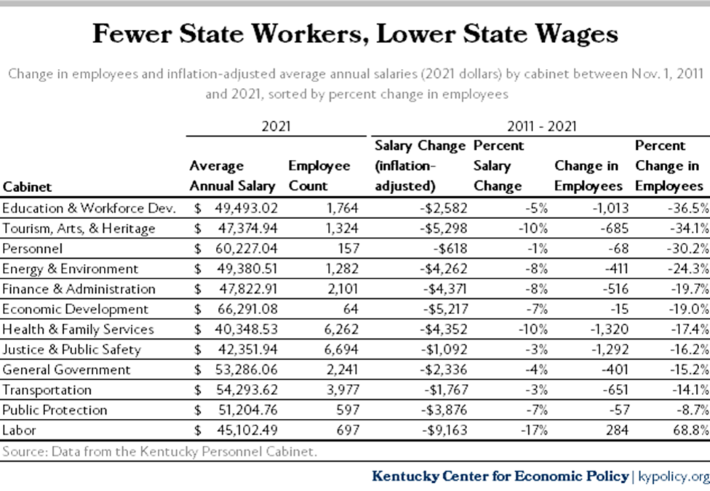

Of the over 30,000 state employees, 27,157 work in the executive branch. The average executive branch salary in 2011 was an inflation-adjusted $49,478. But by 2021 it had fallen 6.2% (or $3,049) to $46,429. Over that same period, the total number of executive branch employees fell by an extraordinary 18.5%, or 6,145 employees. Every cabinet in state government has seen a decline in wages, and nearly every cabinet has substantially fewer employees now than 10 years ago.10

In the context of the economic recovery from COVID, one big consequence of low wages in state government is that, as of November 2021, while all other industries have rehired some or all of the workforce lost in April 2020 at the deepest point of job loss early in the pandemic, state government actually has 4.1% fewer employees.11 A combination of pandemic-related layoffs and poor compensation has led to a large employee shortage. As of November 2021, 21.6% of all authorized, full-time positions in state government were unfilled, leaving 7,136 positions vacant.

The vacancies across state government have significantly impacted the provision of public services. Some of the most damaging impacts are in departments charged with caring for the most vulnerable among us. For example, social workers who serve on the frontline of the state’s child protection services had average caseloads of 26 cases per worker in September 2021, despite a best-practice recommendation for caseloads of 15-18 per worker.12 According to a recent news report, the state needs 900 new social workers to reduce caseloads to a manageable level.13 Yet attracting and retaining new social workers has been nearly impossible under current conditions. The combination of a stressful work environment, low pay and high caseloads has led to significant rates of turnover. In 2021 alone, around 650 caseworkers left their jobs, and as of June 2021, 44% of the social workers at the Department for Community Based Services (DCBS) had less than one year of experience.14 Throughout 2020, DCBS asked outgoing social workers why they chose to quit their jobs and the top responses they gave included:

- Better job opportunities elsewhere,

- poor pay,

- high caseloads, and

- career change.15

In an effort to attract and retain more social workers, the governor increased their pay by 10% beginning Dec. 16, 2021, but even with the increase, the starting salary for the position of Social Service Worker I (social workers with less than a year of experience) is $37,009 per year, or around $17 per hour. That is still well below the amount needed for a modest but secure livelihood for a family of 4 in Kentucky, and although it is a start, it simply will not be enough to both retain current workers and attract the number of new workers needed to significantly reduce caseloads.16 The House-proposed 2022–2024 state budget includes a raise of $9,600 for social workers over the course of the biennium, and increases the starting wage for social workers by 10%. This is in addition to the 6% across-the-board pay raise for all state employees also proposed in the House budget bill.17

Another example is the Department of Public Advocacy (DPA), the agency responsible for providing representation in the courts for people who are charged with a criminal offense but cannot afford to hire an attorney. Public defense is constitutionally required in Kentucky, but inadequate funding is significantly compromising the ability of DPA to provide these services. According to testimony provided by the Public Advocate before a legislative committee in August 2021, DPA lost 22 employees including 13 staff attorneys and 4 supervisors just in the month of July — constituting 4% of statewide staff.18 The impact of these losses in individual counties has been devastating with offices in Stanton and Maysville experiencing caseload increases of 33% because remaining attorneys must assume new cases. Since that testimony in August, DPA has lost 84 more employees or 15% of the statewide workforce.19 DPA is constantly hiring, but the low salaries and high caseloads make it increasingly difficult for DPA to retain staff.

Unlike many other areas in state government where competition for employees is primarily with the private sector, DPA actually loses a significant number of employees to local prosecutors’ offices and other state agencies that can offer higher salaries — often up to 30% more than DPA can pay. DPA is the largest employer of staff attorneys in state government, with 40% of the total (an additional 31% are employed by local prosecutors and the remaining 29% are employed by other executive branch agencies), yet only 3 attorneys employed by DPA are among the 200 highest paid state government staff attorneys (those earning $65,240 or higher). Meanwhile, DPA attorneys constitute 139 of the 200 lowest paid staff attorneys (earning $50,004 or lower), or almost 70% of that group.20 DPA cannot pay higher salaries because all available resources are used to hire additional attorneys to reduce unmanageable caseloads for existing attorneys. The department has an ethical responsibility to keep caseloads at a level where competent representation can be provided.

Increasing DPA salaries to better compete with other attorney positions will require an appropriation in addition to any across-the-board raises that might be provided. In his testimony before the legislative committee, the Public Advocate asked for an increase of $5.6 million to address these issues.21 In response to this need, the House-proposed 2022–2024 budget includes $7.1 million in each of the next two fiscal years to increase salaries for several positions in DPA including staff attorneys and managers of attorneys.22

In another example, the Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) had a vacancy rate of nearly 33% at the end of November in its detention centers, and, due to staffing shortages, had to temporarily close one facility and reassign staff from other areas to work in facilities that remained open. DJJ also reported a 31% vacancy rate in the youth worker position, and a 21% vacancy rate in the youth worker supervisor position.23 Vacancy rates and severe staffing shortages have been an ongoing problem at DJJ. In 2017, DJJ workers received a 20% pay increase in an attempt to address significant retention issues following a year in which 151 people were hired but 181 resigned.24 Even after that significant increase, the staffing issues remain, and the starting salary for a Youth Worker I in a juvenile justice facility today is just $33,000 annually.25 Despite these continuing issues, the House-proposed budget does not include any extra compensation for youth workers beyond the one-time 6% across the board increase in 2023.

Outside the executive branch, Chief Justice Minton has warned that the low pay and high turnover in Kentucky’s courts is hurting the quality of the state’s justice system. For example, non-elected employees in the judicial branch earn an average wage of $36,000. Among non-elected judicial branch employees, 82% are in low-paying positions with starting salaries between $23,600 and $30,900.26 Coupled with the fact that over half of judicial branch employees no longer have a traditional, defined benefit pension plan, this low pay has led to a turnover rate of 1/3 of the workforce (over 1,000 employees) in the past four years.27 In urban areas, turnover is closer to 40% per year, and in special courts (such as drug court, mental health court and veterans court), six counties are completely unstaffed, while Jefferson County’s special courts have a 2/3 vacancy rate.28

Among elected Judicial employees – primarily judges and circuit court clerks – pay is also very low. Kentucky district and circuit court judges’ pay ranks 51st out of 55 states, territories and D.C. Kentucky appellate court judges’ pay ranks 41st out of 42 and Kentucky supreme court justices’ pay ranks 52nd out of 55. Circuit court clerks earn 11% to 13% less than similar county positions in Kentucky.29

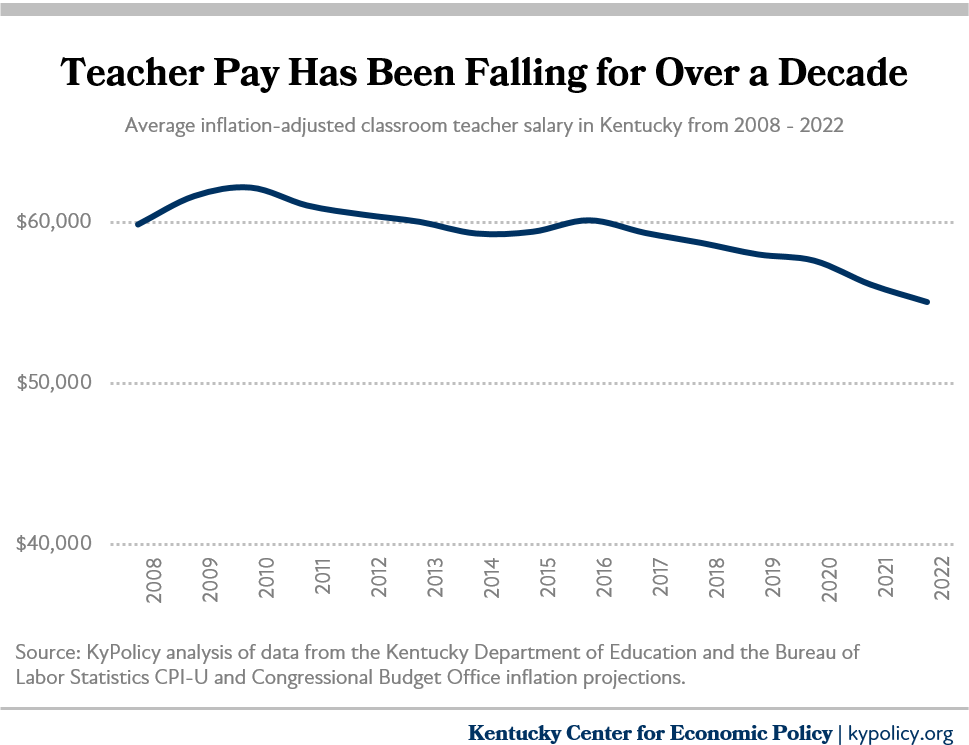

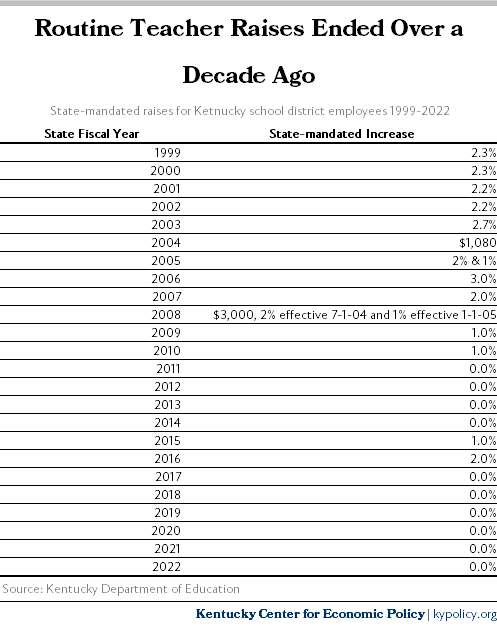

Teacher pay has also been stagnant and needs state-funded increase

Teachers and school employees are another set of public employees in need of raises. As the baby boomer generation retires, school districts are facing growing difficulty in attracting teachers and staff; a recent report called the national teacher shortage “real, large and growing, and worse than we thought.”30 Bigger class sizes and a lack of raises due to state budget cuts are among the issues affecting teacher attraction and retention.31 And school employees have shouldered the stress of greater health risk and new duties such as policing masking and social distancing during the COVID-19 crisis. As of January 2022, new teachers in Kentucky will receive a reduced, hybrid pension benefit that shifts more of the risk to them as a result of House Bill 258 passed in 2021. Districts have also had well-publicized trouble attracting and retaining bus drivers due to low pay. Teachers and other school employees are not included in the one-time 6% raise for state employees included in the House Budget, and the modest changes in school funding contained in the House Budget would make providing much-needed raises difficult in many districts.32

Like state employees, teachers have not received a meaningful state raise since 2008 (see the table in Appendix 2). Because of this, the average inflation-adjusted salary for classroom teachers has fallen $4,824 or 8.1% between 2008 and 2022.33

When looking at the district level, average inflation-adjusted teacher pay has fallen much further in some districts. With one exception (Fayette County) teachers have seen a pay cut on average in every school district – ranging from -25.9% in Russellville Independent to -4.5% in Franklin County since 2008.

While teacher pay is funded through a combination of state and local sources, there is a large and growing gap in the resources available to districts in wealthy and poor areas of the state.34 This means that any substantial, mandated salary increase for school district employees will need to be supported with state resources, which the legislature has also chosen to let decline since 2008.35

Ending full public pensions and eroding health benefits has made retention difficult

State government salaries in Kentucky have never been equal to those in the private sector for people with comparable levels of education. However, because the state offered a good retirement plan and generous health insurance benefits, it was not difficult for the state to recruit and retain workers for people willing to trade the higher salary for the good benefits. In addition, the pension system served as an incentive for workers to stay in state government because full retirement benefits required 27 years of service to qualify.

But beginning in 2013, the General Assembly made drastic changes to state employee retirement benefits that significantly altered this dynamic. The legislature suspended cost-of-living adjustments for retirees and eliminated the traditional defined benefit plan. They replaced it with a less attractive hybrid cash balance plan for new employees, leaving them exposed to more financial risk in the long term. Additionally, the state began requiring state employees to contribute more to their health plans that year, leading to a 48% increase in employee health spending in 2014 compared to 2008.36 Neither of those changes has been reversed or improved since that time. Combined with stagnant pay, the weaker retirement plan and reduced health benefits have created little incentive for new people to seek employment with state government. But more critically, it has reduced the incentive for existing employees to remain in state government when private sector pay is much better. Unlike with defined benefit pensions, the portability of cash balance plans provides less of an incentive for employees to stay in public service, and the risk of a lower ultimate retirement benefit compared to a pension makes public service less attractive.

State employees work and live in every county in the commonwealth

State workers across the commonwealth contribute to their communities through their work, but they also contribute to their local economies through their personal spending. Therefore, the impact of the state government workforce crisis is twofold. State employees across the three branches of state government brought $1.4 billion into their communities in 2021. As a share of total wages in the state in 2021, wages from state employment made up 1.6%, but locally that ratio ranged from 0.3% in Boone County to 31.4% in Franklin County.37

Past budget and tax decisions have come at the expense of Kentucky’s state workforce and the public services they deliver to communities

Because of the many years without raises and the significant reductions in benefits, state government agencies cannot hire and retain the employees needed to fulfill their responsibilities. Remaining employees shoulder more responsibility, leading to burnout and increased retirements and resignations, further depleting the workforce — a vicious cycle that will only worsen until significant and sustained investments are made in the people who are the backbone of public services in state government.

Past choices made by the General Assembly to cut taxes rather than support the public workforce are a driver of this cycle. The 2022–2024 Tax Expenditure Analysis identifies close to $19 billion in total tax expenditures over the 2022–2024 biennium, compared to $27.3 billion in appropriations in the proposed House budget over the same period (excluding the legislative branch budget, which has not yet been introduced).38 The $19 billion includes $555 million in new tax breaks enacted in recent years including over $43 million for refundable credits for the film industry, $388.8 million from the low tax rate on casino-style slot machines, over $100 million for the newly expanded historic preservation tax credit and $23.2 million for cryptocurrency mining. Because of the way tax expenditures work, these programs receive priority funding over everything else that state government provides and pays for, including state worker salaries. Thus, before the first dollar is spent to pay state workers, Hollywood production companies, slot machine operators, real estate developers and cryptocurrency miners get paid.

In large part as a result of choices like these, Kentucky’s state budget was cut 20 times during the Great Recession and subsequent recovery, and the legislature allowed state salaries to stagnate and benefits to atrophy.

Substantial raises for state workers are necessary

To restore the 5% annual increment required under law for the next two years would cost $163 million from the General Fund.39 However, such an investment does not begin to make up for the erosion from the fact that a 5% raise has not been provided since 2001. The House-proposed 2022–2024 budget includes a 6% raise for 2023 only and a 0% raise in 2024. A 6% raise is below annual inflation which was 7% in 2021.40

Kentucky has the resources to make a much more robust investment in the state workforce and the critical services they provide. The state has a projected $3.4 billion in extra General Fund resources due to past and estimated budget surpluses, more than enough to give state employees a long-overdue raise that is at a sufficient level to make up some of the ground that has been lost since the Great Recession.41

We can also afford to make needed special increases for certain positions like the House proposed budget does for public defenders and social workers by including other groups of employees that face severe shortages due to wages and working conditions, such as teachers, other school employees and direct care workers providing supports for people with disabilities. And the state should increase the minimum wage for all public employees to at least $15 an hour.

Investing in Kentucky’s ability to provide core services through an adequate public sector workforce should be a top priority for the extra resources available in the new two-year budget. Our ability to build a thriving commonwealth that is educated, healthy and safe depends on having the frontline workers in place that play such vital roles.

Appendix 1: Annual State Employee Increments, 1983–2021

Appendix 2: Annual State-Mandated School District Increments 1999-2022

- State employee data from an open records request to the Kentucky Personnel Cabinet received Dec. 22, 2021. KRS 18A.355, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=1432.

- Jason Bailey, “House Budget Provides Only Modest Reinvestment Despite Large Budget Surplus,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 7, 2021, https://kypolicy.org/house-budget-provides-only-modest-reinvestment-despite-large-budget-surplus/.

- Open records request to the Kentucky Personnel Cabinet. Elise Gould, Zane Mokhiber and Kathleen Bryant, “Family Budget Calculator,” Economic Policy Institute, Mar. 13, 2018, https://www.epi.org/resources/budget/.

- Jeffrey H Keefe, “Public Versus Private Employee Costs in Kentucky: Comparing Apples to Apples,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, July 2012, https://kypolicy.org/public-versus-private-employee-costs-kentucky-comparing-apples-apples-2/.

- Gerina Whethers, “2019-2020 Annual Report,” Kentucky Personnel Cabinet, Feb. 3, 2021, https://personnel.ky.gov/Annual%20Reports/2019-20%20Annual%20Report.pdf. According to an open records request from the Kentucky Personnel Cabinet, there have been only 4 across-the-board increments since 2008 and all of them were 1% with the exception of a pay equity adjustment in 2014 that averaged slightly higher.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages for all private sector employees in Kentucky adjusted for the state fiscal year 2020 CPI-U.

- State employee data from an open records request to the Kentucky Personnel Cabinet received on Nov. 21, 2019.

- Dustin Pugel, “Eastern Kentucky, Veterans Affairs Workers Benefiting From Raised Minimum Wage for State Workers,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Dec. 7, 2015, https://kypolicy.org/eastern-kentucky-veterans-affairs-workers-benefitting-from-raised-minimum-wage-for-state-workers/.

- John Cheves, “Bevin Orders Marriage License Changes; Reverses Beshear on Felon Voting Rights, Minimum Wage,” Lexington Herald Leader, Dec. 23, 2015, https://www.kentucky.com/news/politics-government/article51139910.html.

- The Education and Workforce Development and Labor cabinets complicate this picture somewhat as there have been multiple reorganizations that have shifted agencies between the two over the past decade, making a comparison over the course of a decade less reliable.

- Current Employment Statistics State and Metro Area Employment, Hours & Earnings for Kentucky in April 2020 and September 2021.

- Marta Miranda-Straub and Lesa Dennis, “DCBS Workforce Challenges and Initiatives,” Kentucky Department for Community Based Services, Oct. 13, 2021, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/320/13455/10%2013%202021%20Straub%20-%20DCBS%20Presentation.pdf.

- Jasmine Demers, “Citing low pay and crushing caseloads, Ky. Governor gives social workers a raise,” 89.3 WPFL, December 8, 2021,https://wfpl.org/citing-low-pay-and-crushing-caseloads-ky-governor-gives-social-workers-a-raise/.

- Joe Ragusa, “Lawmakers Discuss Social Worker Shortage in Kentucky,” Spectrum News 1, October 1, 2021, https://spectrumnews1.com/ky/louisville/news/2021/10/14/kentucky-social-workers-leaving-in-droves. Marta Miranda-Straub and Lesa Dennis, “DCBS Workforce Challenges and Initiatives” Kentucky Department for Community Based Services.

- Miranda-Straub and Dennis, “DCBS Workforce Challenges and Initiatives.”

- “Beshear: Social Services Workers Receiving 10% Pay Raise,” Associated Press, Dec. 8, 2021, https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/kentucky/articles/2021-12-08/beshear-social-service-workers-to-receive-10-pay-raise. Salary information from job listings for Social Service Worker I positions on the Kentucky Personnel Cabinet’s website accessed Jan. 6, 2022, https://kypersonnelcabinet.csod.com/ats/careersite/search.aspx?site=2&c=kypersonnelcabinet.

- Bailey, “House Budget Provides Only Modest Reinvestment Despite Large Budget Surplus.”

- Preston, “Where’s My Lawyer?,” written materials provided in conjunction with testimony before the Interim Budget Review Subcommittee on Justice & Judiciary, Aug. 4, 2021, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/17/13394/Aug%204%202021%20Preston%20DPA%20Attorney%20Salaries%20Handout.pdf.

- Conversation with Public Advocate Damon Preston on Dec. 8, 2021.

- Damon Preston, “Where’s My Lawyer?”

- Minutes from the Aug. 4, 2021 Interim Budget Review Subcommittee, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/17/13599/Sept%2024%202021%20BR%20JJ%20August%20Minutes.pdf.

- HB1 22RS, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/22rs/hb1.html.

- John Cheves, “KY Struggles to Staff Juvenile Justice Centers, With Nearly 1 in 3 Jobs Left Open,” Lexington Herald-Leader, Dec. 7, 2021, https://www.kentucky.com/news/politics-government/article256397831.html.

- John Cheves, “Governor Bevin Gives 20 Percent Pay Raises to State’s Juvenile Justice Workers,” Lexington Herald-Leader, March 13, 2017, https://www.kentucky.com/news/politics-government/article137543708.html.

- Kentucky Personnel Cabinet website job posting, https://kypersonnelcabinet.csod.com/ats/careersite/JobDetails.aspx?id=30972&site=2.

- John Minton Jr. testimony in the Kentucky House Appropriations and Revenue Committee on Feb. 1, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cN1EXXMOL9Q.

- John Minton Jr. “Compensation Plan,” Kentucky Court of Justice, Feb. 1, 2022, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/81/13731/KENTUCKY%20COURT%20OF%20JUSTICE%20Compensation%20Plan.pdf

- John Minton Jr. testimony in the Kentucky House Appropriations and Revenue Committee on Feb. 1, 2022.

- John Minton Jr. “Compensation Plan – Elected Officials,” Kentucky Court of Justice, Feb. 1, 2022, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/81/13731/KENTUCKY%20COURT%20OF%20JUSTICE%20Elected%20Officials.pdf.

- Emma Garcia and Elaine Weiss, “The Teacher Shortage Is Real, Large and Growing, and Worse than We Thought,” Economic Policy Institute, March 26, 2019, https://www.epi.org/publication/the-teacher-shortage-is-real-large-and-growing-and-worse-than-we-thought-the-first-report-in-the-perfect-storm-in-the-teacher-labor-market-series.

- Ashley Spalding, “State Budget Cuts to Education Hurt Kentucky’s Classrooms and Kids,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 29, 2018, https://kypolicy.org/state-budget-cuts-education-hurt-kentuckys-classrooms-kids/.

- Bailey, “House Budget Provides Only Modest Reinvestment Despite Large Budget Surplus.”

-

KyPolicy analysis of data from the Kentucky Department of Education, Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI-U and Congressional Budget Office inflation projections accessed on Jan. 31, 2022, https://education.ky.gov/districts/FinRept/Pages/School%20District%20Personnel%20Information.aspx.

- Anna Baumann, “Inequality Between Rich and Poor Kentucky School Districts Grows Again Even as Districts Face New COVID Costs and Looming Revenue Losses,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Sep. 2, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/new-analysis-inequality-between-rich-and-poor-kentucky-school-districts-grows-again-even-as-districts-face-new-covid-costs-and-looming-revenue-losses/.

- Ashley Spalding, “What to Know about Kentucky School Funding as Kids Head Back to School,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Aug. 9, 2021, https://kypolicy.org/what-to-know-about-kentucky-school-funding-as-kids-head-back-to-school/.

- Ashley Spalding, Anna Baumann and Jason Bailey, “Investing In Kentucky’s Future: A Preview of the 2016-2018 Kentucky State Budget,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, January 2016, https://kypolicy.org/investing-in-kentuckys-future-a-preview-of-the-2016-2018-kentucky-state-budget/.

- KyPolicy analysis of data from an open records request to the Kentucky Personnel Cabinet and the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages.

- HB1 22RS.

- HB209 RS22, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/22rs/HB209.html.

- “Consumer Price Index Summary,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, Jan. 12, 2022, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cpi.nr0.htm.

- Jason Bailey, “Unprecedented Surplus Presents Opportunity to Both Reinvest in Kentucky’s Budget and Build Rainy Day Fund,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Oct. 20, 2021, https://kypolicy.org/unprecedented-surplus-opportunity-to-reinvest-in-kentucky-budget-and-build-rainy-day-fund/.