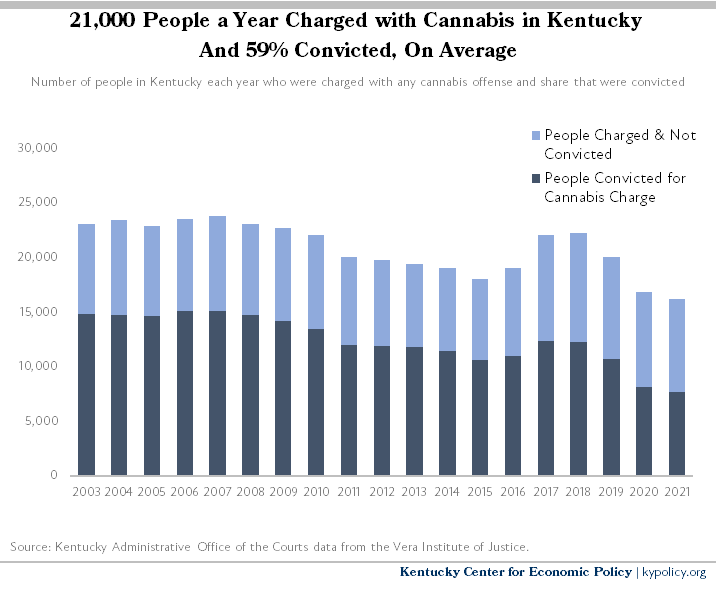

Over the past two decades, as states around the nation have moved to decriminalize and legalize cannabis, more than 300,000 people in Kentucky have been charged with a cannabis-related crime, according to analysis of Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) data. 1 That’s nearly two people charged every hour, every day between June 2002 and July 2022. And more than half of those charged were convicted of a cannabis-related offense.2 All told, one out of 10 of the 3.1 million people charged with a crime in Kentucky in that time period faced cannabis charges.

Every corner of the commonwealth has seen people charged with cannabis crimes with some counties having dozens charged and others tens of thousands. Data also reveals starkly different conviction rates, with some rural areas nearly twice as likely to convict someone for a cannabis charge than Kentucky’s biggest city. Still, as much of the country has moved to more permissive policies, Kentucky continues to subject people to incarceration, burdensome fines, community supervision, and criminal charges for cannabis crimes. These consequences have lasting, harmful effects on people’s economic security, employment, health, housing and ability to fully participate in community life. And these consequences often fall disproportionately on low-income and Black and Brown Kentuckians.

Recently, Kentucky has taken small steps to reduce its carceral approach to cannabis. At least one county (Jefferson) limits cannabis possession prosecution, the legislature reduced the penalty for cannabis possession in 2011 and the 2023 General Assembly took an important step in legalizing cannabis for certain medical uses starting in 2025.3 But Kentucky is still one of only 18 states that continues to criminalize cannabis despite dramatic shifts in public opinion. Lawmakers should maintain the momentum toward a new approach that fully acknowledges the harms of cannabis criminalization for individuals, communities and Kentucky as a whole.

The extensive scope of cannabis criminalization in Kentucky

Over the past two decades (between July 1, 2002 and June 29, 2022), an estimated 303,264 people in Kentucky were charged with any kind of cannabis offense, according to AOC data made available by the Vera Institute of Justice.4 In 2019 alone, before the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to fewer arrests and case delays due to court closures, 20,087 people were charged with a cannabis offense, and 53% were convicted.5

It is also notable that despite evolving public opinion about cannabis use, cannabis conviction rates are somewhat comparable to conviction rates for all offenses. On average, between 2003 and 2021 the conviction rate for people charged with cannabis offenses was 59% and for all offenses was 63%.6 Even with a recent drop, the majority of individuals charged with cannabis cases are in fact convicted.

Cannabis criminalization impacts people across Kentucky. As shown in the table below, the number of people in the Appalachian region of Kentucky charged with cannabis (64,656 people) between July 2002 and June 2022 is close to the number charged in Jefferson County (72,717 people).7 However, the conviction rate in the Appalachian region is significantly higher: 65% convicted compared to 40% in Jefferson County. Western Kentucky is the region with the highest conviction rate for cannabis offenses.

Every Kentucky county had people charged with cannabis offenses during these two decades – from 68 people in Robertson County to 72,717 in Jefferson County. Expressed as the number of annualized cannabis-related charges per 1,000 county residents in the two-decade period, 1.5 people per 1,000 had a cannabis charge in Robertson County in contrast to 8.4 people per 1,000 in Carroll County.8 Lyon County is an outlier, where 16.4 people per 1,000 had a cannabis charge.9

Conviction rates for cannabis ranged from 88% in Casey County to 40% in Jefferson County.

Overview of criminal penalties for cannabis in Kentucky

Cannabis criminalization in the United States dates back to the 1900s and was largely based on xenophobia toward the Mexican immigrants who were most closely associated with the plant.10 By the 1950s, the federal government instituted mandatory minimum sentencing for drug-related offenses, including cannabis.11 While most of these federal laws were repealed a couple of decades later, the war on drugs then emerged, which led to increased federal penalties and three strikes-sentencing for federal drug crimes, with most states also enacting similar penalties.12

Fortunately, shifts in public opinion about how we handle drug offenses, especially those related to cannabis, have started to result in reform of these laws. In 2011, Kentucky reduced the cannabis possession penalty from a Class A misdemeanor to a Class B misdemeanor.13 Last year, President Biden announced he would pardon all federal cannabis possession convictions.14 In November 2022, Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear issued an executive order granting preemptive pardons for medical cannabis purchased in another state.15 And earlier this year, the Kentucky General Assembly passed Senate Bill (SB) 47, initiating the legalization of medical cannabis.16

Yet every year thousands of Kentuckians become system-involved for cannabis charges. Possession, trafficking and cultivation of cannabis remain illegal in Kentucky, with the exception of the newly-passed medical cannabis law that goes into effect in 2025. Potential criminal penalties for cannabis on the books in Kentucky range from a maximum of 45 days in jail with a possible fine for simple possession, anywhere from 90 days to 20 years in prison plus fines for trafficking (depending on the amount), and up to five years for cultivating. In March of this year, 540 Kentuckians were incarcerated on 600 cannabis related felony offenses and 4,912 individuals were on probation or parole for 5,250 cannabis offenses.17

Possession

The most common cannabis charge in Kentucky is possession, a Class B misdemeanor that carries up to 45 days in jail and a fine of up to $250.18 Approximately 277,000 people were charged with cannabis possession in Kentucky between July 2002 and June 2022. Most possession charges do not result in the full statutory penalty but are handled through a citation – a legal document with a mandatory court date – and do not immediately result in arrest or jail time.

In 2019, the Jefferson County Attorney’s Office in Louisville announced it would no longer prosecute cannabis possession cases.19 However, this policy only applies to cases where the individual has one ounce or less, and in cases where cannabis possession is the only or most serious charge. As a result, Jefferson County still has a high number of cannabis possession cases, with more than 250 in 2022.20 The odor or physical discovery of cannabis can also still be used as probable cause for a search, resulting in a spillover effect that leads to other types of charges.21

Trafficking

Trafficking in cannabis – which means to distribute, dispense, or sell – has different penalties depending on the amount:

- Less than eight ounces is a Class A misdemeanor (punishable by 90 days to 12 months in jail and a fine of up to $500) for the first offense and a Class D felony (punishable by one to five years in jail and a fine between $1,000 and $10,000) for subsequent offenses;22

- Between eight ounces and five pounds is a Class D felony for the first offense and a Class C felony (punishable by five to 10 years in prison and a fine between $1,000 and $10,000) for subsequent offenses;

- Five pounds or more is a Class C felony for the first offense and a Class B felony (punishable by 10 to 20 years in prison and a fine between $1,000 and $10,000) for subsequent offenses.23

Additionally, there is a presumption in the law that if a person possesses more than eight ounces of cannabis, the person had the intent to sell or transfer it.24 Therefore, possessing more than eight ounces could be the difference between a possession and a trafficking charge, even if there is no other typical evidence of drug trafficking such as scales, separate packaging or large sums of cash. Trafficking in Kentucky also does not require selling, so an individual could be charged with trafficking for simply sharing cannabis with another person, even when no payment is exchanged.25 As a result, some people face more serious charges due to the obscure differences between possession and trafficking.

Cultivation

Cultivating cannabis – which means planting or harvesting with the intent to transfer or sell – carries its own penalties.26 Cultivating five or more cannabis plants is a Class D felony for the first offense and a Class C felony for subsequent offenses; and cultivation of fewer than five plants is a Class A misdemeanor for the first offense and a Class D felony for subsequent offenses.

Medical cannabis exceptions

The 2023 Kentucky General Assembly passed SB 47, legalizing medical cannabis.27 While the law does not go into effect until 2025, Kentuckians living with a specific list of medical conditions will soon be able to legally use cannabis for treatment.28 The law specifies that medical cannabis must be prescribed by a doctor and cannot be smoked. It also sets possession limits for both patients and caregivers. Though the law is an important first step in recognizing the harms of criminalization, the impact on cannabis charges and convictions will likely be minimal.29

Collateral consequences of cannabis criminalization continue to harm Kentuckians, especially Black and Brown Kentuckians

While most cannabis charges in Kentucky don’t result in jail or prison time, the collateral consequences of even a misdemeanor cannabis possession conviction can include financial burdens and negative impacts on employment, housing, higher education, access to social services and more.30 These harms are disproportionately experienced by low-income and Black and Brown Kentuckians.

Financial consequences

A cannabis conviction in Kentucky often comes with harsh fines and fees.31 People convicted of felonies are subject to fines between $1,000 and $10,000, or double the gain from the commission of the offense, if that amount is greater.32 “Gain” means the amount of money or the value of the property (i.e. cannabis) seized. Those with misdemeanor convictions can be subject to fines between $250 and $500.33 There are also court costs of $100 per case, plus additional add-on court fees to support specific government programs and services.34 In addition, some plea deals may require individuals to complete a cannabis education course, wear a GPS monitor, submit to drug screenings, or meet other requirements that they may have to pay for. Costs, such as fines and fees, can in many cases be waived or reduced for people who are determined to be indigent, but for those who are not, failure to pay fines and fees can result in incarceration.35

Another possible consequence is community supervision, which is typically in the form of probation or parole where a court-ordered sentence is served outside of a jail or prison in which an individual reports to a probation or parole officer. The length and terms of supervision can be burdensome, and if not followed precisely, could result in a technical violation, leading to incarceration.36 In addition, there are monthly supervision fees that must be paid.37 Non-payment of court or supervision fines and fees is considered non-compliance with the terms of community supervision, and could also result in incarceration.

Fees associated with cannabis convictions push people deeper into poverty by taking resources out of household budgets for food, rent, health care, transportation and other basic needs.38

Employment consequences

Criminal background checks are a routine part of the hiring process, and are used by many employers. Simply being charged with a cannabis-related crime, regardless of the seriousness of the offense and regardless of whether a conviction ever resulted, will show up on a background check and could impact educational and employment opportunities.

Many professional licensure boards have discretion to discipline or suspend a professional’s license after a criminal conviction, and many require that any kind of conviction be reported to the board by the professional immediately.39 Further, even a simple cannabis possession conviction has the potential to bar someone from military service, and a trafficking or cultivation conviction is a definite barrier to enlistment.40

Housing and immigration consequences

Certain drug-related convictions, including those involving cannabis, can impact eligibility for federal benefits such as housing. To be considered for Section 8 Housing Voucher benefits in Kentucky, an individual cannot have any “drug-related criminal activity” within the last three years.41

Individuals who are not United States citizens, even those present in the country with legal status, may face loss of immigration status or deportation for cannabis convictions.42A trafficking or cultivation conviction is a deportable offense, while possession is grounds for deportation where the amount is more than 30 grams, or 1.05 ounces.43 The federal regulation for possession is much more restrictive than the state regulation, which covers up to eight ounces for possession. This difference, in combination with the broad application of Kentucky’s trafficking statute, means many people may find themselves in deportation proceedings who would not otherwise if cannabis was legal at the state level.

Some cannabis-related charges may become eligible for expungement, but expungement is not a cure-all.44 The federal government can still access expunged offenses, so military and immigration consequences may persist even after the expungement process.

Disproportionate harm to communities of color

Even when cannabis-focused policing doesn’t result in cannabis-related convictions, individuals and communities still experience harm. For instance, the use of “probable cause” to stop people to search for cannabis and other drugs can have spillover effects that lead to other charges or police violence, as was the case that led to the death of Breonna Taylor.45 Other harms caused by policing include nonfatal injuries, psychological distress and poor mental health.46

Certain people and communities are disparately harmed by all aspects of policing and prosecution for cannabis and other substances. Currently, despite being 8.7% of the statewide population, Black Kentuckians make up 21% of the prison population.47 A 2020 ACLU report found that Black Kentuckians are nearly 10 times more likely to be arrested for cannabis possession than white Kentuckians despite similar rates of use.48 And according to the Kentucky Department of Public Advocacy, data from Fayette County in 2019 shows Black people made up 49% of cannabis possession charges and 59% of cannabis trafficking charges. Meanwhile, Black people make up only 16% of the Fayette County population.49

Additionally, a 2019 investigation by the Courier-Journal found that Black Louisvillians accounted for two-thirds of people charged for cannabis possession and were cited for possession at six times the rate of white people.50 People of color are also more likely to experience physical harm from and be killed by police, and to experience anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress disorder as a result of having contact with police.51 Furthermore, fines (which many people are charged for cannabis offenses) are rooted in historical racism and emerged in the Reconstruction period as a way to punish Black people – also disproportionately harm communities of color.52

Kentucky has made progress in recent years, but more is needed to stop harms

As public opinion around cannabis shifts, there have been positive changes made at the state level in recent years, including Jefferson County limiting prosecution of certain cannabis offenses, and the legislature’s legalization of medical cannabis. However, addressing the enormous human costs of cannabis charges and convictions will require going further, including by taking additional steps to decriminalize and legalize cannabis and thoughtfully remedying past harms of cannabis convictions.

Kentucky should follow other states by moving toward regulating and taxing cannabis

Most states have legalized or decriminalized cannabis in some way, including Kentucky’s neighboring states.53 Illinois, Virginia and Missouri legalized recreational cannabis, while Ohio legalized medical cannabis and Ohioans will vote on a ballot measure whether to legalize recreational cannabis this November.54 Kentucky should recognize the ongoing harms of a incarceration-based approach and begin moving toward a system that regulates and taxes cannabis use.

In addition, Kentucky should take steps to remedy the disproportionate impacts cannabis convictions have had on communities of color. For example, any legalization policy should include proactive steps to ensure the industry is reflective of the community as a whole, and invests tax revenue from the industry in impacted communities.55

Expungement is needed to remedy past harms

While decriminalization and legalization of cannabis would mitigate future harms, many Kentuckians will continue to experience the harms of past enforcement.56 Therefore, any legalization legislation must also include expanded expungement processes for those with cannabis charges or convictions. These processes should exist in addition to Kentucky’s current expungement laws, but provide for automatic, cost-free expungement for cannabis-related offenses to reflect the change in law.57

- Vera institute of Justice analysis of Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) data. KyPolicy uses the term “cannabis” as opposed to “marijuana.” The term marijuana was largely used in the United States to push anti-Mexican immigrant rhetoric related to the substance.

- Convictions are where there was a conviction on a cannabis specific charge, not cases with any conviction.

- Kentucky Legislature, “Acts of the 2023 Regular Session,” Chapter 146, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/23RS/actsmas.pdf.

- Methodological note that the total number of people charged with cannabis counts individuals just once even if they were charged with cannabis in more than one year; however, the data presented for each year includes all individuals charged that year – including those who were charged in other years.

- Louisville Metro Criminal Justice Commission Jail Policy Committee, “Preliminary Assessment – Impact of COVID-19 on Crime, Arrests and Jail Population,” March 2021, https://louisvilleky.gov/criminal-justice-commission/document/crime-arrest-and-jail-population-covid-19-impact. The conviction rates in the data are for the individuals charged with cannabis offenses in a particular year – not the year they were convicted, which could be different.

- Note that a person charged with a cannabis offense in more than one year will be counted in each year they were charged; however, in the total of all individuals charged with cannabis over the two-decade period they are only counted once.

- Note that individuals charged with a cannabis offense on multiple occasions within a region are only counted once, but if a person is charged in multiple regions they are counted once per region in which they were charged. AOC’s regional definitions are: Fayette, Jefferson, Metropolitan Cincinnati Area, Metropolitan Fayette County Area, Metropolitan Jefferson County Area, Micropolitan, Micropolitan Appalachian, Other Metropolitan, Rural and Rural Appalachian.

- Note that individuals charged with a cannabis offense on multiple occasions within a county are only counted once, but if a person is charged in multiple counties they are counted once per county in which they were charged.

- Lyon was an outlier in a separate data source regarding drug arrests as well, with the per-capita arrest rate more than double that of some nearby counties in 2019. Kentucky State Police, “Crime in Kentucky 2019,” https://transportation.ky.gov/HighwaySafety/Documents/cik_2019.pdf.

- Marijuana Timeline, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/dope/etc/cron.html.

- Marijuana Timeline, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/dope/etc/cron.html.

- Marijuana Timeline, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/dope/etc/cron.html.

- Kentucky Legislature, “Acts of the 2011 Regular Session,” Chapter 2, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/11RS/documents/0002.pdf.

- Office of the Pardon Attorney, U.S. Department of Justice, “Presidential Proclamation on Marijuana Possession,” https://www.justice.gov/pardon/presidential-proclamation-marijuana-possession.

- TKTKTK

- Kentucky Legislature, “Acts of the 2023 Regular Session,” Chapter 146, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/23RS/actsmas.pdf.

- Kentucky Department of Corrections, “Corrections Impact Statement,” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/recorddocuments/note/23RS/sb47/CI.pdf.

- Kentucky Revised Statutes 218A.1422, “Possession of Marijuana – Penalty – Maximum Term of Incarceration (Effective until January 1, 2025),” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=39536#:~:text=(1)%20A%20person%20is%20guilty%20of%20possession%20of%20marijuana%20when,%2Dfive%20(45)%20days.

- Joe Sonka, “Possession of Small Amounts of Marijuana Will No Longer Be Prosecuted in Louisville,” Courier-Journal, Aug. 28, 2019, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/politics/2019/08/28/jefferson-county-prosecutor-drops-small-marijuana-possession-cases-louisville-kentucky/2138978001/.

- The Department of Information and Technology Services Research and Statistics, “Possession of Marijuana Charges Convicted Jan. 1 – Oct. 20, 2022 Jefferson County,” Administrative Office of the Courts, Oct. 21, 2022, https://kycourts.gov/AOC/Information-and-Technology/Analytics/Custom%20Reports/Possession_of_Marijuana_Charges_Convicted_CY_22_YTD_Jefferson.pdf.

- Louisville Metro Police Department, “Medical Marijuana Executive Order General Memorandum #23-003,” Jan. 24, 2023, https://www.leoweekly.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/General-Memorandum-23-003-Medical-Marijuana-Executive-Order.pdf?x35890.

- Kentucky Revised Statutes 218A.1421, “Trafficking in Marijuana – Penalties (Effective Until January 1, 2025),” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=9650.

- Note that fines cannot be imposed against any person determined by the court to be indigent.

- Kentucky Revised Statutes 218A.1421, “Trafficking in Marijuana – Penalties (Effective Until January 1, 2025),” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=9650.

- Kentucky Revised Statutes 218A.010, “Definitions for Chapter,” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=54047.

- Kentucky Revised Statutes 218A.1423, “Marijuana Cultivation – Penalties (Effective Until January 1, 2025),” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=9652.

- Kentucky Legislature, “Acts of the 2023 Regular Session.”

- The conditions covered by Senate Bill 47 are: any stage or type of cancer; chronic, severe, or debilitating pain; epilepsy or any other intractable seizure disorder; multiple sclerosis, muscle spasms, or spasticity; chronic nausea that has proven resistant to other conventional medical treatments; post-traumatic stress disorder; and any other condition that the Kentucky Center for Cannabis at the University of Kentucky determines could be helped by use.

- Kentucky Department of Corrections, “Corrections Impact Statement,” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/recorddocuments/note/23RS/sb47/CI.pdf.

- Associated Press, “Beshear Seeks Details on Marijuana Possession Convictions,” U.S. News and World Report, Oct. 13, 2022, https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/kentucky/articles/2022-10-13/beshear-seeks-details-on-marijuana-possession-convictions.

- Kaylee Raymer, “Report: Criminal Fines and Fees Drive up Incarceration, Push Kentuckians Deeper Into Poverty,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Aug. 9, 2023, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-criminal-legal-system-fines-and-fees/.

- Kentucky Revised Statutes 534.030, “Fines for Felonies,” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=20097.

- Kentucky Revised Statutes 534.040, “Fines for Misdemeanors and Violations,” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=20098.

- Kentucky Revised Statutes 24A.175, “Court Costs for Criminal Cases in District Court – Payment Required – Exceptions – Treatment of Minor Defendant,” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=46762. Kentucky Revised Statutes 24A.176, “Additional Costs Imposed in Criminal Cases – Funds Distributed to Local Governments and Counties – Funds Used for Police, Jails, and Transport of Prisoners,” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=20697. Kentucky Revised Statutes 24A.179, “Additional Fee for Expenses of Kentucky Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force,” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=44674. Kentucky Revised Statutes 24A.185, “Assessment by the Fiscal Court of Additional Fees and Costs,” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=20701.

- Whether or not someone is indigent is guided by statute, but is not a uniform process. Indigency is a determination made by the individual judge presiding over the case, so such determinations can vary from courtroom to courtroom. Kentucky Revised Statutes 31.120, “Determination of Whether Person Needy – Factors for Determination – Affidavit of Indigency,” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=43333.

- Human Rights Watch, “Revoked: How Probation and Parole Feed Mass Incarceration in the United States,” July 31, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/07/31/revoked/how-probation-and-parole-feed-mass-incarceration-united-states.

- Kentucky Revised Statutes 439.315, “Payment of Fee by Released Person – Amount – Waiver of Payment – Applicable to Persons Released by County Containing City of the First Class or Urban-County Government,” https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=19166.

- Courtney Sanders and Michael Leachman, “Step One to an Antiracist State Revenue Policy: Eliminate Criminal Justice Fees and Reform Fines,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Sept. 17, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/step-one-to-an-antiracist-state-revenue-policy-eliminate-criminal.

- Kentucky Board of Nursing, “Mandatory Reporting of Criminal Convictions,” Feb. 2023, https://kbn.ky.gov/KBN%20Documents/reporting-criminal-convictions-brochure.pdf. Kentucky Court Rules of the Supreme Court 3.130, Rules of Professional Conduct Rule 3.130(8.3), “Reporting Professional Misconduct,” Aug. 15, 2022, https://govt.westlaw.com/kyrules/Document/NFCE86A0028F211ED9F64D8129F531DA3?viewType=FullText&originationContext=documenttoc&transitionType=CategoryPageItem&contextData=(sc.Default). Kentucky Board of Medical Licensure, “Board and Criminal Action Reporting Requirement,” https://kbml.ky.gov/board/Pages/Board-and-Criminal-Action-Reporting-Requirement.aspx#:~:text=According%20to%20201%20KAR%209,of%20the%20entry%20of%20judgment.

- United States Army Regulation 601-210 Ch.4-6, https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN6642-AR_601-210-001-WEB-1.pdf.

- Kentucky Housing Corporation, “Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher Program Landlord Orientation Booklet, https://www.kyhousing.org/Rental/Documents/Landlord%20Orientation%20Book.pdf.

- Kentucky Department of Public Advocacy, “Collateral Consequences of Criminal Convictions in Kentucky,” June 2013, https://dpa.ky.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/CollateralConsequencesManualFINAL051513.pdf.

- United States Code Ch. 8 Sect. 1227(2)(B)(i), “Deportable Aliens,” https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title8-section1227&num=0&edition=prelim.

- Under current Kentucky laws, an individual may petition the court for expungement. All misdemeanor convictions and a list of select Class D felony convictions are expungement-eligible. The earliest convictions can be expunged is five years after completion of the sentence, and only if the individual has not been convicted of any other offenses during that waiting period. Kentucky Department of Public Advocacy and Clean Slate Kentucky, “Expungement Guidebook,” https://dpa.ky.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Expungement-Guidebook-updated-6.16.2023.pdf.

- Carmen Mitchell, “Banning No-Knock Warrants is an Important First Step in Addressing Police Violence Through Demilitarization, Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Dec. 18, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/banning-no-knock-warrants-first-step-in-addressing-police-violence-demilitarization/.

- American Public Health Association, “Addressing Law Enforcement Violence as a Public Health Issue,” Nov. 13, 2018, https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2019/01/29/law-enforcement-violence.

- United States Census Bureau, “Quick Facts,” https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US,KY,louisvillejeffersoncountymetrogovernmentbalancekentucky,louisvillecitykentucky,lexingtonfayetteurbancountykentucky,bowlinggreencitykentucky/RHI225221. Retrieved Aug. 28, 2023. Kentucky Department of Corrections, “Inmate Profiles July 15, 2023,” https://corrections.ky.gov/About/researchandstats/Documents/Monthly%20Report/2022/Inmate%20Profile%2007-2023.pdf.

- Ezekiel Edwards, et al., “A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform,” American Civil Liberties Union, https://www.aclu.org/report/tale-two-countries-racially-targeted-arrests-era-marijuana-reform.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “Quick Facts – Fayette County, Kentucky,” Population Estimates July 1, 2022, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/fayettecountykentucky/PST045222.

- Andrew Wolfson and Jesse Hazel, “You’re More Likely to be Busted for Weed in Louisville if You’re Black,” Courier-Journal, Jan. 25, 2019, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/crime/2019/01/25/marijuana-laws-louisville-african-americans-busted-more-for-pot/1409913002/.

- American Public Health Association, “Addressing Law Enforcement Violence as a Public Health Issue.”

- Sanders, “Step One to an Antiracist State Revenue Policy.”

- DISA, “Marijuana Legality by State,” updated Sept. 1, 2023, https://disa.com/marijuana-legality-by-state. National Conference of State Legislatures, “State Medical Cannabis Laws,” Jun. 22, 2023, https://www.ncsl.org/health/state-medical-cannabis-laws#:~:text=Medical%2DUse%20Update,1%20below%20for%20additional%20information.

- National Conference on State Legislatures, “State Medical Cannabis Laws.”

- National Cannabis Industry Association Policy Council, “Increasing Equity in the Cannabis Industry: Six Achievable Goals for Policy Makers,” March 2019, https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/790303/NCIA%20White%20Papers/PolicyCouncil_SocialEquity_updated4.19_digital_v3.pdf.

- Edwards, et al., “A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform.”

- This idea is not unprecedented, as other states included automated and expanded expungement processes in their cannabis legalization legislation. In California, courts are automatically required to expunge certain cannabis-related convictions without the individual having to first file a petition. This became law years after cannabis legalization when legislators realized the continued harm that cannabis convictions had on residents. Illinois now also automatically expunges minor cannabis offenses and convictions. Delaware has a similar provision.