To view this as a PDF, click here.

The governor has proposed changes to Kentucky’s Medicaid program, arguing they are necessary to “ensure long-term sustainability of the Medicaid program.” 1 But the small amount of state savings projected from the plan come from covering fewer people, which would move Kentucky backwards on our healthcare progress. 2 And the administration’s approach to Medicaid is missing a key strategy for financial sustainability that has been pursued by other states — an increase in the provider taxes paid by hospitals that have greatly benefitted from Medicaid expansion.

In fact, not only has Kentucky so far passed up the opportunity to increase its hospital provider tax to help pay for Medicaid expansion, the state has also capped the tax so it is based on revenues hospitals received in 2006 rather than today, despite the fact they are collecting billions more in receipts now thanks in part to the expansion. 3 Removing the cap would generate more revenue to help pay for the state and federal investments in Medicaid that benefit hospitals, improve Kentucky’s budget situation and allow us to continue the progress we’re experiencing through expanded healthcare coverage.

Capping of hospital provider tax a big drain on revenue

Kentucky has faced tight budgets in recent years that have resulted in cuts to a variety of critical investments. The state has enacted 16 rounds of cuts since 2008, resulting in funding reductions of 15 to 50 percent for many parts of government, rising university and community college tuition and reduction in a variety of services. While the Great Recession played a big role in revenue shortfalls, the state’s fiscal problems are also the result of a General Fund revenue stream that does not keep up with growth in the economy because of too many holes in the tax code. 4

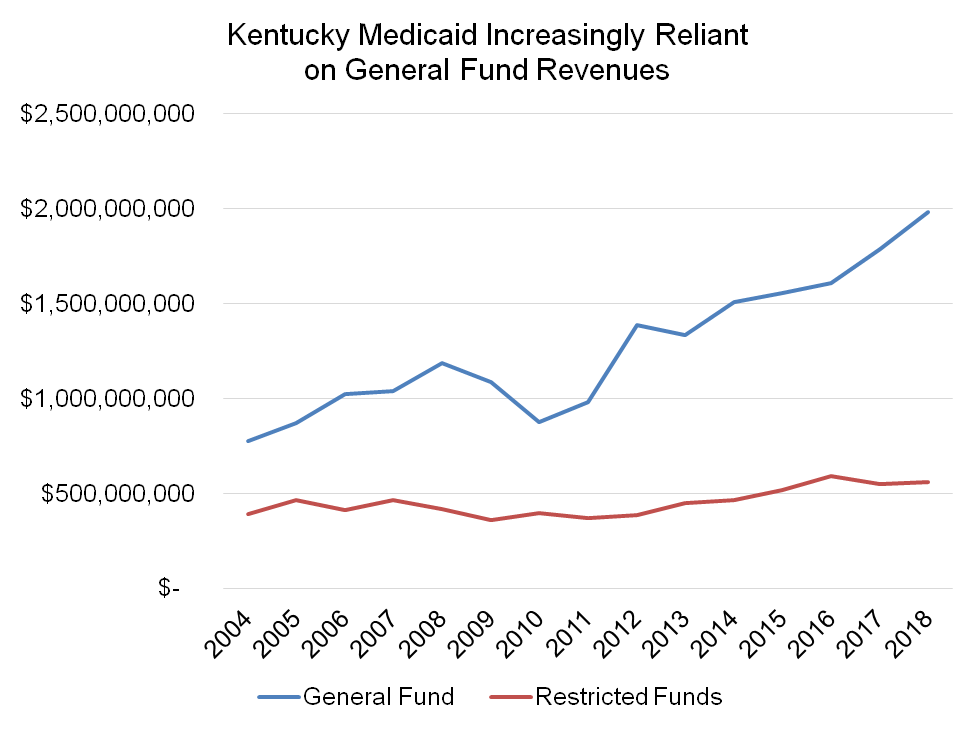

At the same time General Fund revenue has eroded, Kentucky has become more reliant on it in recent years for state funding of Medicaid. Medicaid is paid for primarily with federal dollars, but must be matched with state money. For its state match, Kentucky uses a combination of General Fund appropriations as well as a variety of restricted funds including provider taxes, intergovernmental transfers, a tax on managed care organizations, legal settlements, penalties and interest and other sources.

As can be seen in the graph below, restricted fund dollars for Medicaid have been essentially flat over the last 14 years even while General Fund monies have increased. While restricted funds covered 34 percent of state Medicaid costs in 2004, they only pay for 22 percent today.

Source: KCEP analysis of Office of the State Budget Director data.

Kentucky’s health care provider taxes generated $294 million of the $522 million in restricted funds used for Medicaid in 2015. The provider taxes include a tax of 2.5 percent on hospitals’ gross revenues, a 5.5 percent tax on intermediate care facilities, a 2 percent tax on nursing homes for non-Medicare patients and a 2 percent on licensed home healthcare services. Of that $294 million, $183 million or 62 percent comes from the hospital provider tax. 5

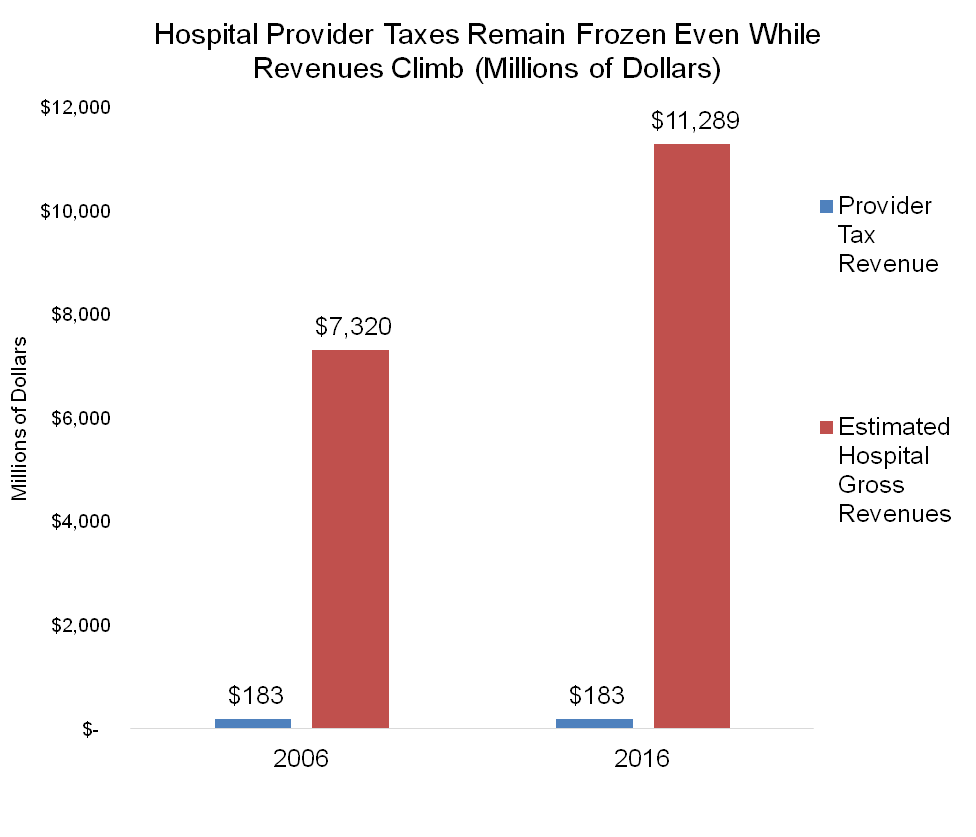

However, the 2.5 percent tax on hospitals is not based on their current revenues, but on revenues received in 2006. The hospital provider tax was established in 1994, and for the first dozen years receipts from the tax grew with hospital revenues, rising from $72.6 million in 1994 to $183 million in 2006. 6 But the 2007 Kentucky General Assembly put a cap on the tax, freezing it based on hospitals’ 2006 revenues. 7

The provider taxes collected from hospitals have remained at $183 million a year since then, even while the revenues received by hospitals have increased dramatically. Simply eliminating the cap – so that the 2.5 percent tax applied to 2016 revenues – would generate $99.2 million more according to the Legislative Research Commission. That implies hospital gross revenues have climbed from $7.3 billion in 2006 ($183 million is 2.5 percent of $7.3 billion) to $11.3 billion in 2016. That is a 54 percent increase in revenues over the last ten years without any increase in hospital provider tax receipts (see graph below). As a result, the effective rate hospitals pay has fallen from 2.5 percent to 1.6 percent.

Source: KCEP analysis based on data from Legislative Research Commission, Kentucky Hospital Association.

Source: KCEP analysis based on data from Legislative Research Commission, Kentucky Hospital Association.

The capping of the hospital provider tax is not the only tax break for hospitals. In 2016, 93 of Kentucky’s 132 hospitals are classified as nonprofit organizations, making them exempt from property taxes as well as corporate income taxes. In addition, health services are exempt from sales taxes.

Hospitals are benefiting from Medicaid expansion

Increases in hospitals’ revenues are in substantial part because of increases in Medicaid reimbursements which grew from $992 million in 2006 to $1.397 billion by 2013, or an increase of 41 percent, according to the Cabinet for Health and Family Services. Reimbursements climbed even higher thanks to Medicaid expansion, which grew the number of Kentuckians covered by health insurance by over 440,000. Between January 2014 and October 2015, as expansion was being implemented, hospitals received $1.345 billion in reimbursements for the expansion population alone, or 46 percent of expansion payments to all types of health providers. 8

Along with increases in revenues, hospitals have seen a large decrease in charity care and other care to uninsured Kentuckians—a 79 percent decline from 2013, before Medicaid expansion went into effect, to 2015. Whereas hospitals had $2.57 billion in such charges in 2013, they had only $552 million in 2015, a decline of $2.02 billion. 9 While hospitals will see a decline in the payments they previously received for caring for the uninsured (known as Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments), the Cabinet for Health and Family Services noted that the additional revenues from Medicaid expansion substantially exceed the revenue they will lose from reductions in DSH payments. 10

Other states are using provider taxes to help fund Medicaid expansion

Provider taxes are commonly used to help fund Medicaid. Every state but Alaska has one or more type of provider tax. In 2015, 44 states put taxes on nursing facilities, 39 on hospitals and 37 on intermediate care facilities. 11

The federal government allows states to use provider taxes to help fund Medicaid as long as several rules are followed. They must be broad-based and uniform, covering all providers in a particular class like hospitals, nursing facilities, and managed care organizations. They also must not guarantee that providers are held harmless from the tax by returning their payments to them in the form of higher reimbursements.

A number of states have increased their provider taxes in recent years. The share of state Medicaid funds coming from provider taxes and intergovernmental transfers increased in 37 states and for the states in total from 2008 to 2012 even while they decreased over that time period in Kentucky, according to a Government Accountability Office report. 12 In 2016, 6 states increased the rates for hospital taxes, 10 states did so in 2015 and 6 states in 2014. The following states specifically increased provider taxes as a way to help pay the state’s cost for Medicaid expansion:

- Indiana expanded Medicaid with the help of monies from Indiana’s cigarette tax and an increase in the hospital tax beginning in 2017, which are expected to generate $959 million of the $1.6 billion in state expansion costs from 2015-2021. Indiana is the Kentucky governor’s stated model for changes to Medicaid, but his plan does not include this revenue element.

- Arizona started taxing hospitals to help fund Medicaid expansion in 2014, and the tax increased in 2015. Regulations allow it to be adjusted based on beneficiaries and costs.

- Ohio’s fee on hospitals increased from 2.66 percent to 4 percent in the second year of the expansion.

- Colorado used its hospital tax to help fund Medicaid expansion as well as an increase in coverage for children and pregnant women. 13

- Louisiana created a hospital provider fee in 2014 via constitutional amendment and subsequent legislative action; the state is using the revenue to help reduce the fiscal impact of expansion. 14

Also, in Tennessee hospitals offered to pay for the entire state costs of expanding Medicaid through higher taxes if the state would move forward. 15 Other states where conversations around increasing provider taxes to pay for Medicaid expansion have been under way include Utah, Kansas, Mississippi and Alaska (which currently has no provider tax). In addition, California and Nevada told the Kaiser Foundation in a 2015 survey (as did Kentucky under the previous administration) that they plan to increase the tax. 16

Typically, a portion of increased provider taxes are used to raise reimbursement rates. A Medicaid rate increase for providers subject to the hospital tax is permissible as long as it doesn’t generate payments to providers in a way that holds them harmless from the tax. With Kentucky’s high federal match rate for Medicaid, using some of the revenue for this purpose limits the impact of a higher tax on hospitals while still providing a substantial benefit to the state budget.

Ending hospital provider tax break would help protect Medicaid and promote budget sustainability

Kentucky should end the tax break that freezes its provider tax even while hospitals’ revenues continue to grow. Removing the cap would generate $99.2 million a year more and allow revenues to keep pace with growth in the sector in the future. The annual benefit from ending the tax break is more than Kentucky is projected to save by creating new barriers to coverage in its Medicaid waiver proposal (which is projected at an average of $66.3 million a year over the five years of the demonstration). 17 Ending the hospital tax break could be also part of a package; for example, a combination of ending the tax break on hospitals, raising the tobacco tax in recognition of the health costs of tobacco use, and increasing Kentucky’s minimum wage would generate enough revenue and Medicaid cost savings to pay the state’s share of Medicaid expansion when fully implemented in 2021. 18

Given Kentucky’s health challenges, we cannot afford to go backwards on the access to health care made available because of the Medicaid expansion by creating new barriers to coverage. Thankfully there are commonsense revenue options like ending the hospital tax break that would allow us to shore up the state budget without undermining Kentuckians’ health.

- “Governor Bevin Submits Innovative, Transformative Plan to Improve Health Outcomes to Federal Government,” http://kentucky.gov/Pages/Activity-stream.aspx?n=KentuckyGovernor&prId=146. ↩

- Dustin Pugel, “Modest Savings from Medicaid Waiver Ignore Added Costs and Mostly Don’t Come from Expansion Population,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, August 31, 2016, https://kypolicy.org/modest-savings-medicaid-waiver-mostly-dont-come-expansion-population-diminished-added-costs/. ↩

- Justin Tapp, “Hospitals Should Help Fund Medicaid,” The Courier-Journal, August 24, 2016, http://www.courier-journal.com/story/opinion/contributors/2016/08/24/comment-hospitals-should-help-fund-medicaid/89216126/. ↩

- Micah Johnson, “Kentucky’s Revenue Not Keeping Up with Economy,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, August 16, 2016, https://kypolicy.org/kentuckys-revenue-not-keeping-economy/. ↩

- National Conference of State Legislatures, “Health Provider and Industry State Taxes and Fees,” February 1, 2016, http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/health-provider-and-industry-state-taxes-and-fees.aspx#State_Provider_Taxes_or_Fees_. KRS 142.301, http://www.lrc.ky.gov/statutes/statute.aspx?id=40749. Kentucky ended its managed care organization fee in 2010 after the Department of Health and Human Services issued rules disallowing it, and ended its pharmacy tax in 1999. ↩

- KRS 142.303, http://www.lrc.ky.gov/statutes/statute.aspx?id=29203. Kentucky Hospital Association, “Kentucky Hospital Statistics,” 2009, http://chfs.ky.gov/NR/rdonlyres/F5A3C9DB-E94D-4425-9A15-8E5B8DA62BC2/0/KYHospitalStatistics2009.pdf. ↩

- House Bill 244, 2007 Regular Session of the Kentucky General Assembly, http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/07rs/HB244.htm. ↩

- Cabinet for Health and Family Services, “Medicaid Expansion, Enrollment, and Reimbursement in Kentucky,” November 13, 2015. ↩

- Foundation for Healthy Kentucky, “Kentucky Hospital Charity Care, Care to Uninsured Dropped 76.9 Percent from 2012 to 2015,” September 29, 2016, http://healthy-ky.org/news-events/newsroom/kentucky-hospital-charity-care-care-uninsured-dropped-769-percent-2012-2015. SHADAC analysis of data from the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services Kentucky Outpatient Hospital Administrative Claims Data. ↩

- Cabinet for Health and Family Services, “Medicaid Expansion, Enrollment, and Reimbursement in Kentucky,” November 13, 2015. ↩

- Vernon K. Smith, et al., “Medicaid Reforms to Expand Coverage, Control Costs and Improve Care,” Kaiser Family Foundation and National Association of Medicaid Directors, October 2015, http://files.kff.org/attachment/report-medicaid-reforms-to-expand-coverage-control-costs-and-improve-care-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2015-and-2016. ↩

- United States Government Accountability Office, “Medicaid Financing: States’ Increased Reliance on Funds from Health Care Providers and Local Governments Warrants Improved CMS Data Collection,” July 2014, http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-627. ↩

- Community Catalyst, “Health Care Provider Assessments: A State-Based Funding Solution for Closing the Coverage Gap,” July 2015, http://www.communitycatalyst.org/resources/publications/document/ProviderAssessmentsforCTG_06.10.15.pdf. ↩

- Jan Moller, Louisiana Budget Project, personal communication. ↩

- Alex Tolbert, “Why Medicaid Expansion Failed in Tennessee,” The Tennessean, February 10, 2015, http://www.tennessean.com/story/money/2015/02/10/medicaid-expansion-failed-tennessee/23168957/. ↩

- Smith, “Medicaid Reforms to Expand Coverage, Control Costs and Improve Care.” ↩

- Pugel, “Modest Savings from Medicaid Waiver.” ↩

- Raising the cigarette tax by 50 cents a pack and making associated increases to other tobacco taxes would generate approximately $107 million. House Bill 247, 2016 Regular Session of the Kentucky General Assembly, http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/16RS/HB247.htm. Raising Kentucky’s minimum wage to $10.10 an hour would shift an estimated 16,700 families from traditional state-finance Medicaid to expansion Medicaid, which has a higher federal match rate. That would save the state an estimated $34 million a year. Rachel West, Center for American Progress, personal communication. ↩