As the 2022 Kentucky General Assembly approaches, some interested in more tax cuts for the wealthy are again pushing to shift Kentucky’s tax system away from income taxes and toward regressive consumption taxes. Such a shift will mean a tax cut for corporations and powerful people who have seen their already high incomes grow in the pandemic, and a tax increase for middle- and low-income Kentuckians, making our tax code more “upside down” than it already is and worsening racial inequities.

In addition, a shift will make it more difficult for Kentucky to sustain even current, inadequate levels of investment in the keys to economic growth: a strong education system, modern infrastructure, improved health and a good quality of life. That is because consumption-based tax systems fail to keep pace with growth in our economy. Prosperous states have moved their tax systems in the exact opposite direction in recent years, increasing taxes on millionaires whose incomes are growing rapidly and closing corporate tax loopholes in order to better afford crucial public investments.

Tax shift is a tax cut for the powerful few, tax increase for the many

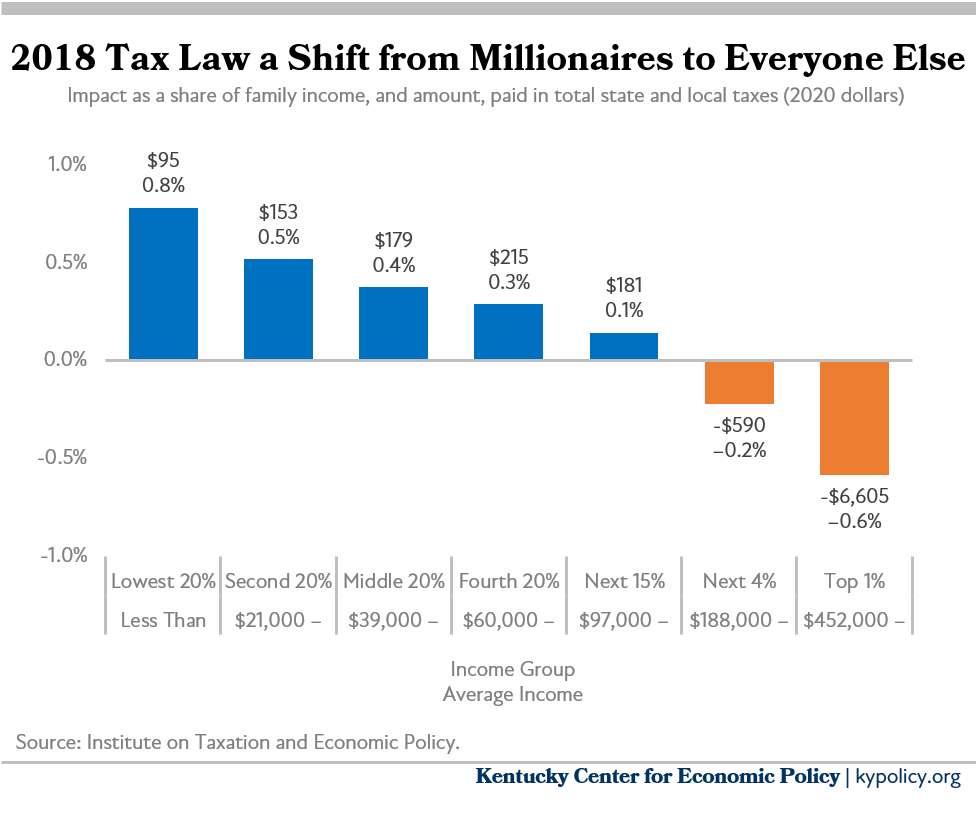

In 2018 the Kentucky General Assembly made a significant move in the direction of a more upside down or “regressive” tax system by replacing the state’s graduated income tax of up to 6% with a flat tax of 5%. They paid for this cut in part by expanding the sales tax to services like car repair and pet grooming.

An analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) showed that based on income, the bottom 95% of Kentuckians paid more on average in taxes because of the shift from income to consumption taxes in the legislation, while the richest 5% on average received a tax cut. In 2020 dollars, the richest 1% — whose incomes average $1.1 million a year — received an average tax cut of $6,605, as shown in the graph below.

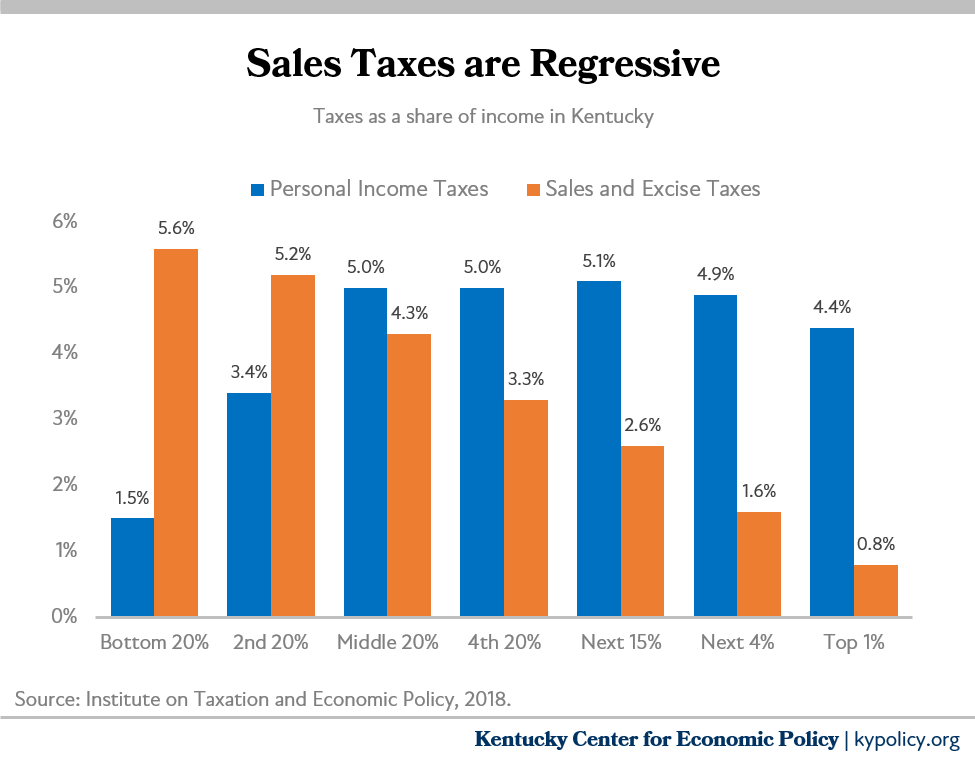

A swap from income taxes to consumption taxes significantly shifts who pays for public services. Low- and middle-income people spend all or most of their income, with little left for savings, resulting in a larger share of their income being spent on items that are subject to the sales tax. In contrast, those at the top are able to save a significant portion of their income, making the sales tax less significant to their family budgets.

In addition, Kentucky has exempted people below the poverty line from the income tax since a “family size credit” was enacted during the Fletcher administration in 2005. So further cuts to the income tax in exchange for higher sales taxes harm people with incomes under the poverty line the most because they receive no benefit from an income tax decrease, while they feel the biggest impact of higher sales taxes. In other words, tax shifts like the one passed in 2018 tax people further into poverty.

The graph below illustrates who currently pays income taxes versus who pays sales and excise taxes in Kentucky by income group.

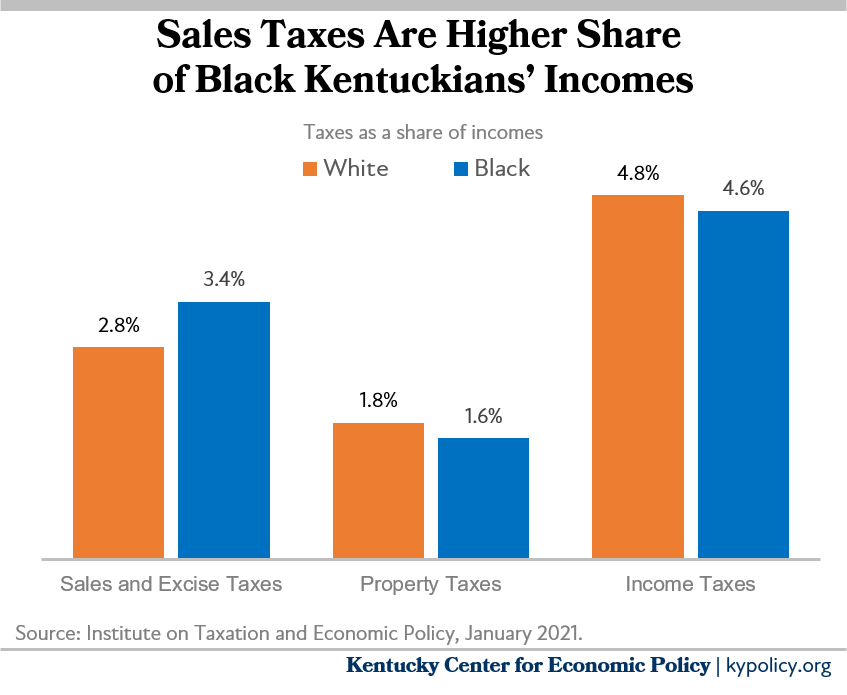

A shift to consumption taxes also worsens existing racial inequities in our tax system. Kentuckians of color have disproportionately low incomes compared to white Kentuckians due to historic and current patterns of discrimination. Black Kentuckians are disproportionately represented in the poorest quintile (20%) of all Kentuckians, with 29% of Black Kentuckians in that income group compared to only 19% of white Kentuckians. Because of this disparity, Black Kentuckians pay 3.4% of their income in sales and excise taxes on average while white Kentuckians pay only 2.8% on average. ITEP also reports that because the overall state and local tax system in Kentucky is regressive, Black Kentuckians already pay more in total state and local taxes at 9.6% of their income on average compared to 9.4% for white Kentuckians.

A shift away from income taxes to sales taxes will therefore mean higher reliance on taxes from Black Kentuckians despite the fact they have less ability to pay on average and face higher overall taxes already. Last year the Kentucky General Assembly created the Commission on Race and Access to Opportunity to address barriers and correct historic inequities. But a shift away from income to sales taxes will widen rather than narrow a key existing disparity.

A further cut in income taxes will be extremely costly

Another reduction in the state income tax rate would be extraordinarily costly. Simply reducing the 5% income tax rate by one percentage point to 4% would cost Kentucky’s General Fund approximately $1.1 billion, according to ITEP. To put that cost in context, just a one percentage point drop in the income tax rate would cost the budget over $200 million more a year in General Fund dollars than the state spends on all of its postsecondary institutions combined: 8 universities and 16 community colleges, whose tuitions have been rising in part due to state budget cuts. To drop the rate 0.1 percentage points from 5% to 4.9% would cost more than Kentucky spends on preschool.

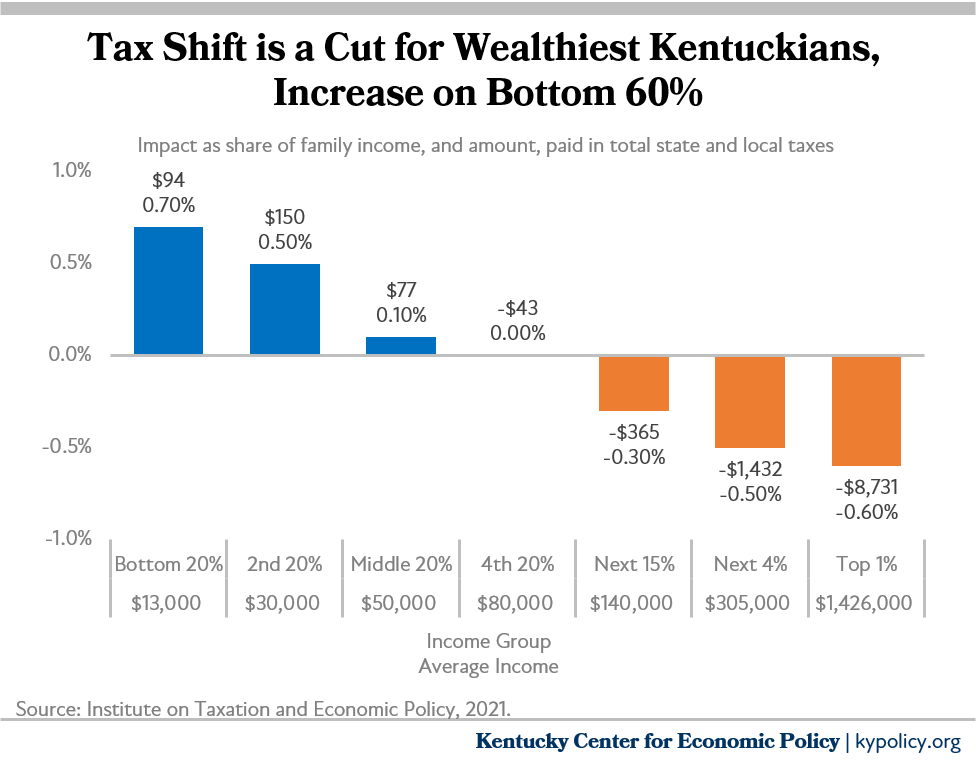

To try to make up the lost revenue from lowering the income tax to 4%, the state would have to increase the sales tax rate from 6% to 7.4%. That would give Kentucky the highest state sales tax rate in the country. Such a shift would worsen the existing inequities in who pays taxes, as shown in the graph below. The bottom 60% of Kentuckians would pay more in taxes on average while those with highest incomes would receive a tax cut. The top 1% would receive an average tax cut of $8,731.

Kentucky has a historic opportunity in the 2022 General Assembly because federal aid from the American Rescue Plan Act, CARES Act and other relief legislation stimulated state budget surpluses amounting to billions of dollars. After 20 rounds of state budget cuts since the Great Recession, this surplus gives Kentucky the chance to begin reinvesting in vital services. But the state could easily squander a large portion of it through an income tax cut while harming our ability to generate revenue beyond the period in which the surplus is available for use.

Tax shift will harm the state’s budget and hinder economic growth

A shift away from income taxes toward regressive consumption taxes is a very risky proposition when it comes to our ability to sustain Kentucky’s schools, infrastructure, health, human services and more. Like many states, income inequality is growing rapidly in Kentucky. The wealthiest 1% of Kentuckians have received more than 30% of income growth in the state since 1973, while the incomes of everyone else have been relatively stagnant. In an economy where most income growth is at the top while low and middle-income families have seen little if any wage growth, it is predictable that taxing wealthy people less while taxing people with low and middle-incomes more will result in slower revenue growth. States that lack income taxes struggle to afford public services.

But Kentucky could be left in even worse fiscal shape from a shift away from income taxes than other states that have much different economies. For example, states without income taxes like Florida, Tennessee and Nevada have much bigger tourist economies due to specific local amenities (including beaches, the Great Smoky Mountains, and the Las Vegas strip, respectively), while no-income tax states like Texas and Alaska have large natural resource sectors that no longer exist in Kentucky due to the decline of coal. Those unique conditions create particular opportunities to raise significant revenues from other sectors of the economy in those states — sectors that Kentucky lacks, meaning the commonwealth cannot follow these states without substantial harm to its budget.

Those who are interested in tax cuts for the wealthy falsely claim that states with less reliance on income taxes are doing better economically. In fact, the states with the highest top income tax rates are doing as well or better than states without income taxes when it comes to measures like GDP growth, GDP growth per capita and average income growth. Another report by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found that of 8 states that have enacted higher taxes on millionaires in recent years, most had resulting economic and income growth at least as strong as their neighbors. And despite claims that a shift away from income taxes is about increasing Kentucky’s low labor force participation rate, states with the highest top income tax rates have better employment rates than states with no income tax at all.

Rather than moving toward consumption-based tax systems, prosperous states are shoring up their revenues by increasing taxes on top earners and closing corporate loopholes. States like Arizona, Colorado, Minnesota, Maryland, Washington, Oregon and more are creating millionaires’ taxes, limiting deductions and loopholes for high-income households, increasing taxes on capital gains, and requiring corporations to pay what they owe.

Over the long term, those states generating additional revenue by increasing taxes at the top are enhancing their capacity for economic development. State public investments in high-quality early childhood education, removing economic barriers facing low- and moderate-income families, improving college affordability, strengthening family finances, modernizing the state’s physical and technological infrastructure, improving the health of the population and more are essential to creating more innovative and prosperous state economies.