As Kentucky college students head back to school, many face serious financial challenges as state support for higher education continues to fall short. In the new state budget, funding for our public universities and community colleges was cut yet again, and state financial aid remains inadequate, making it more difficult for many Kentuckians to successfully complete college.

Kentucky’s Public Universities and Community Colleges Have Even Fewer Resources Than Before

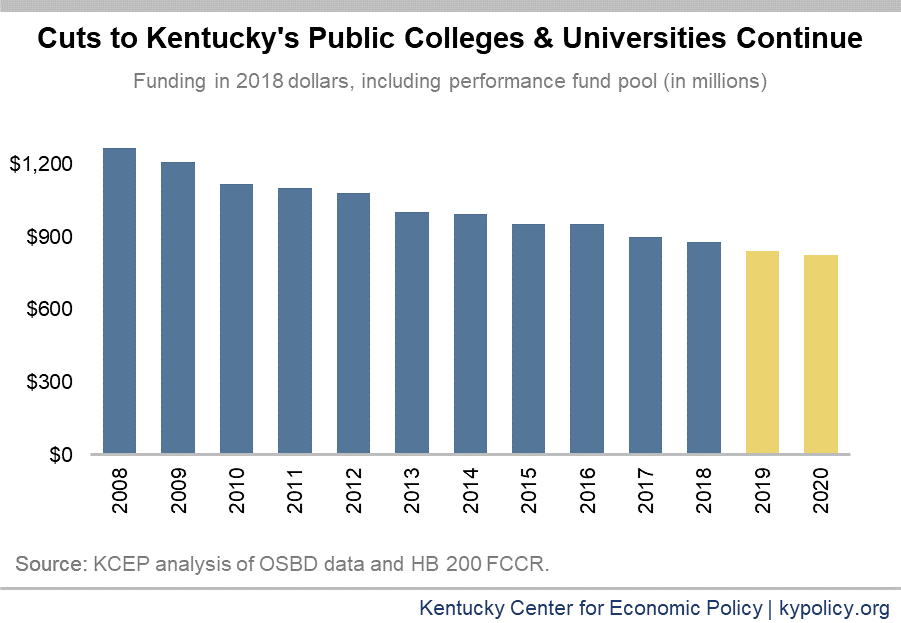

According to a national report, last year Kentucky was in the worst 10 states for per-student cuts to higher education since 2008. Kentucky’s public universities and community colleges received even less state funding this year, with additional cuts to public postsecondary institutions of about 6 percent in 2019. The state invested some additional funds in performance funding pools (one for community colleges and one for universities), which meant some universities and community colleges were able to help mitigate the impact of cuts, while others were not. Overall, Kentucky’s public higher education institutions have been cut by 34 percent between 2008 and 2019, adjusting for inflation.

Budget Cuts Impact Quality of Education and Student Success

Budget Cuts Impact Quality of Education and Student Success

The new cuts on top of round after round of previous budget cuts will impact the quality of education in various ways. Kentucky universities and community colleges have made big cuts to academic programs, faculty and staff positions, and student services/supports that are critical – especially to the success of low-income students and students of color. These cuts have likely impacted the ability of our public institutions to reduce achievement gaps. The most recent state budget cuts have already resulted in the elimination of 153 positions and a long list of academic programs at Eastern Kentucky University (EKU), 140 jobs being cut at Western Kentucky University (WKU) as well as the closure of an academic college, 63 positions being eliminated at Northern Kentucky University (NKU) and 26 at Morehead State University (MoSU).

State budget cuts harm students in numerous ways. For some, the high costs of college and lack of available resources and supports prevent degree completion by creating insurmountable roadblocks.

Tuition Increases

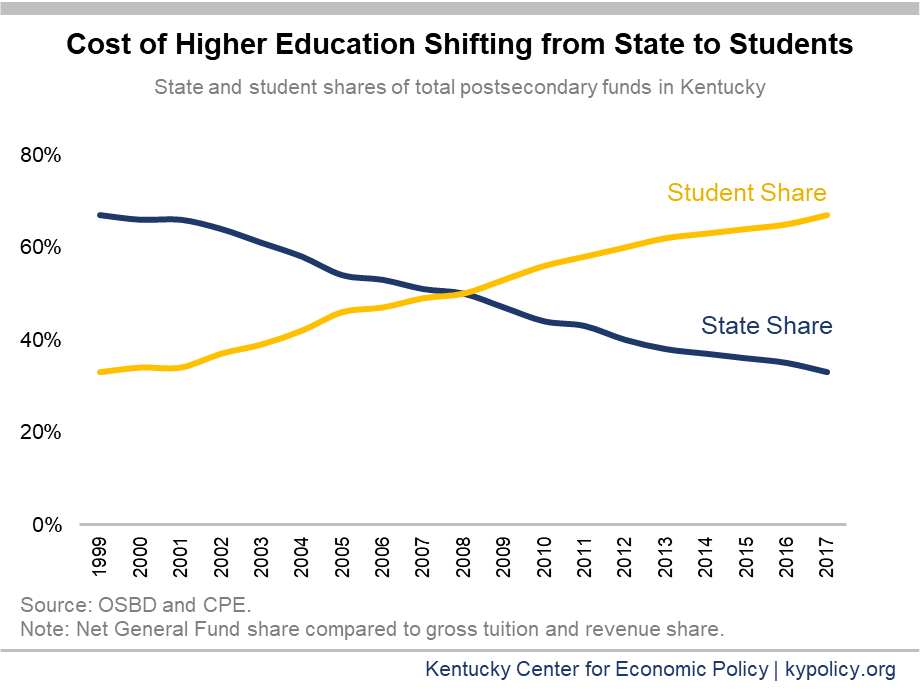

These state budget cuts have driven steep tuition increases over the past decade, with the costs of higher education increasingly borne by students, as seen in the graph below. While this year’s tuition and fee increases are less than in recent years — ranging from no increase at MoSU and EKU to 4 percent at WKU and 4.3 percent at the state’s community colleges — the fact that tuition has been rising while wages have largely been stagnant means that college remains unaffordable for many. Tuition increases are especially a barrier for students of color, who are less likely to enroll as the cost of tuition goes up, and for low-income students.

Increasing Student Debt and High Default Rates

Increasing Student Debt and High Default Rates

Not surprisingly, student debt has been rising alongside tuition increases. For those graduating with a bachelor’s degree in Kentucky, average student debt was $28,910 in 2016 (the most recent information available), up from $15,951 in 2008, an 81 percent increase (61 percent in inflation-adjust terms). Another big concern is that many students even with low levels of debt are unable to complete a degree or credential and unable to pay off debt; these are the students typically represented in the student loan default rate (a very modest measure of the severity of the student debt problem) published each September by the U.S. Department of Education. Kentucky has had a high rate of student loan default in recent years — particularly at the community colleges and several of the comprehensive universities.

Increased Pressure to Work More

A large share of college students work while taking classes. However, it’s difficult for a student to earn enough in wages to fully meet college costs, and working too many hours can undermine student success. A recent national report found that just 9 percent of beginning community college students who worked full-time during their first year had graduated two years later, compared to 20 percent of students who worked 20 hours or fewer.

Food and Housing Insecurity

As college affordability has worsened, food and housing insecurity among college students has become increasingly common. Food insecurity is correlated with lower grades in college, and housing insecurity is a barrier to college completion and credit attainment. A recent national survey found that lacking such basics is a significant public health issue across the country that undermines college graduate rates.

Among those who are especially at risk for “basic needs insecurity” are former foster youth, student parents, African American students, students receiving Pell Grants (a federal grant for low-income students), and those who identify as homosexual and/or non-binary gender. Student-veterans are also at greater risk of housing insecurity and homelessness.

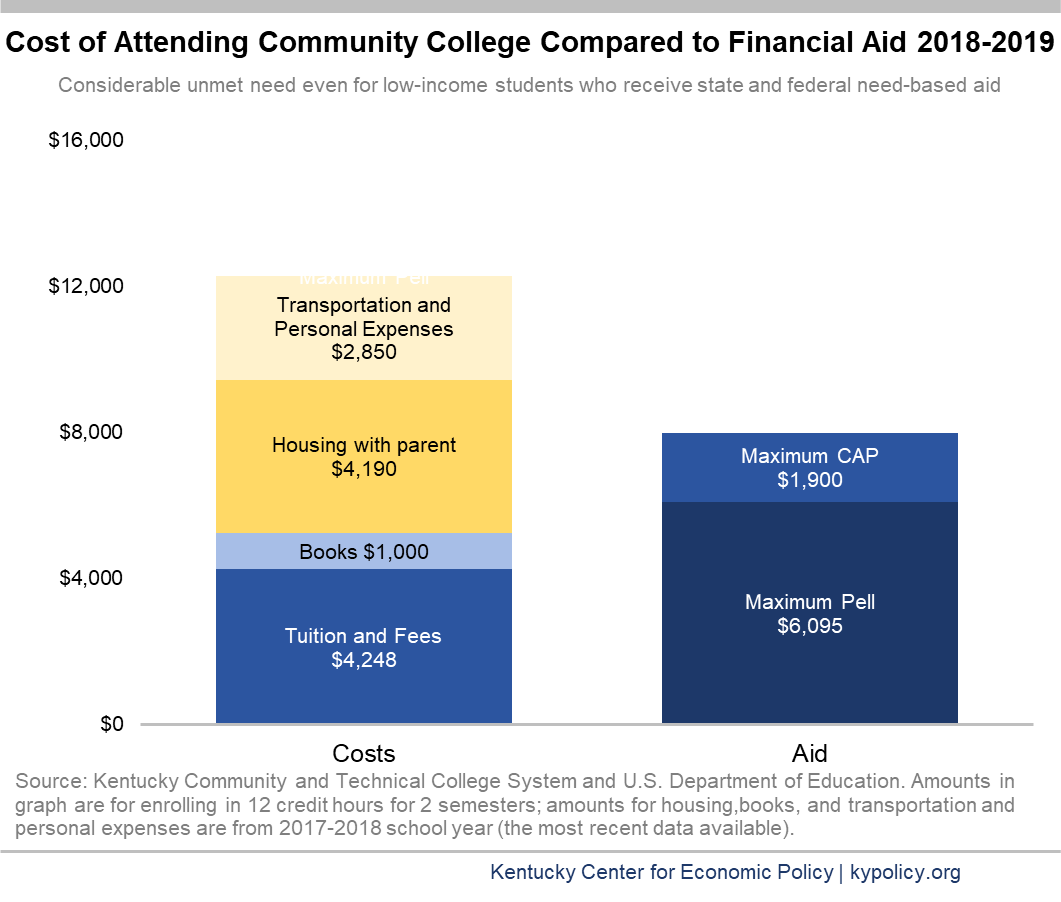

Given Kentucky’s college affordability challenges, many Kentucky college students likely struggle with food and housing insecurity. Comparing a very modest estimate of college costs – the total cost of attendance at a Kentucky community college for students who live with a parent (whose costs might be lower as a result) – to the maximum amount covered by a Pell Grant plus state need-based College Access Program (CAP) scholarship, can provide some insight into this struggle.

State Took Just a Few Small Steps Forward With Financial Aid

The state took a couple of steps forward with financial aid this year, though inadequate to address broader affordability issues.

This year the Work Ready Scholarship has been expanded beyond just short-term credentials in the five industries considered to be high-demand, including health care and advanced manufacturing, to associate’s degrees in the same occupational areas and to high school students who take courses in these programs through dual enrollment. The Work Ready expansion seems especially positive as associate’s degrees are known to have a better return on investment than short-term postsecondary education credentials. However, the scholarship is still very limited because it covers tuition and fees at a community college (or an equivalent amount in qualifying programs at a university) only if Pell Grants and other scholarships don’t cover these costs (this is called a “last dollar” program). In this way, it does not help pay for the many additional costs of college such as books, food and transportation discussed previously.

State need-based scholarships received a small increase of $15 million in 2019 — the equivalent of approximately 8,300 additional student scholarships. However, the state is still not putting in the full amount required by statute, and many low-income students who qualify for scholarships do not receive them due to a lack of funds. Meanwhile the maximum amount of a CAP scholarship (the state’s primary need-based financial aid program) has been stuck at $1,900 for many years despite the growing cost of college.

Strategies to Encourage Completion Fail to Consider Financial Realities for Many Students

A new strategy from the Council on Postsecondary Education (CPE) is “15 to Finish” — the purpose of which is to improve degree completion rates by encouraging students to attend full-time. To support the strategy, Kentucky’s community college system is investing in a new $500 scholarship for students pursuing an associate’s degree who complete at least 15 credit hours in a semester and then re-enroll for 15 hours the following semester. The reality is that many students who attend part-time simply cannot afford to attend full-time (probably also why they are less likely to graduate) and the program’s small incentive is not enough to make up the difference. In-state students pay $177 per credit hour to attend a Kentucky community college, so the scholarship would roughly cover the cost of one 3 credit-hour class out of the 15 hours required to receive the scholarship (and it’s only paid out after the courses are successfully completed). It does not compensate students for the time they may need to be working to support themselves and/or their families. As a result, those who struggle the most financially — parents and low-income students who are also perhaps most at risk of leaving college — will not benefit.

As noted by higher education expert Dr. Sara Goldrick-Rab, “People don’t take less than 15 credits because they ‘don’t know’ more makes you go faster. They take less because it’s what they can handle.” Goldrick-Rab sees the “15 to Finish” push as problematic in part because it does not consider that “students who move faster vs. slower are often different people who are destined to finish college at different rates independent of their pace.”

In order for the state to meet its ambitious higher education goals, including closing achievement gaps, greater investment in the public universities and community colleges is needed. More robust state financial aid and adequate student support services could make a big difference for many Kentucky college students.