Unemployment insurance (UI) is one of the most effective programs available to help laid-off workers meet their basic needs and allow economies to bounce back during downturns. As a partial wage replacement, UI supports families so they can better make ends meet during hard times and keeps businesses afloat by preventing even steeper declines in consumer spending during recessions. A robust state UI program can make economic downturns shorter and shallower than they would otherwise be.

However, the COVID-19 economic crisis has made clear the serious inadequacies of Kentucky’s unemployment insurance system. The news has been filled with heartbreaking stories of people whose benefits have been delayed or denied, and Kentuckians stood in long lines outside unemployment offices to get answers on their applications. Uniquely restrictive and outdated eligibility rules, antiquated computer systems and inadequate agency staffing have kept many Kentucky workers from qualifying for benefits and resulted in severe delays for others. The state’s modest benefit amounts had to be substantially supplemented by Congress to allow families to pay their bills and avoid a severe depression.

The seeds of Kentucky’s unemployment system problems were planted through past state policy decisions and a failure to make needed investments over decades. To prevent similar challenges in the future, the Kentucky General Assembly must modernize the state’s system to improve access to benefits through measures that have worked in other states. Legislators should also protect the system from attempts to further reduce supports for laid-off Kentuckians – as have been proposed in recent sessions of the General Assembly. The problems the state has faced in providing UI were avoidable, and will recur in future recessions unless Kentucky makes needed improvements and avoids harmful new cuts.

Click here for a PDF version of this brief.

Unemployment insurance is a critical anti-recessionary tool and safety net program

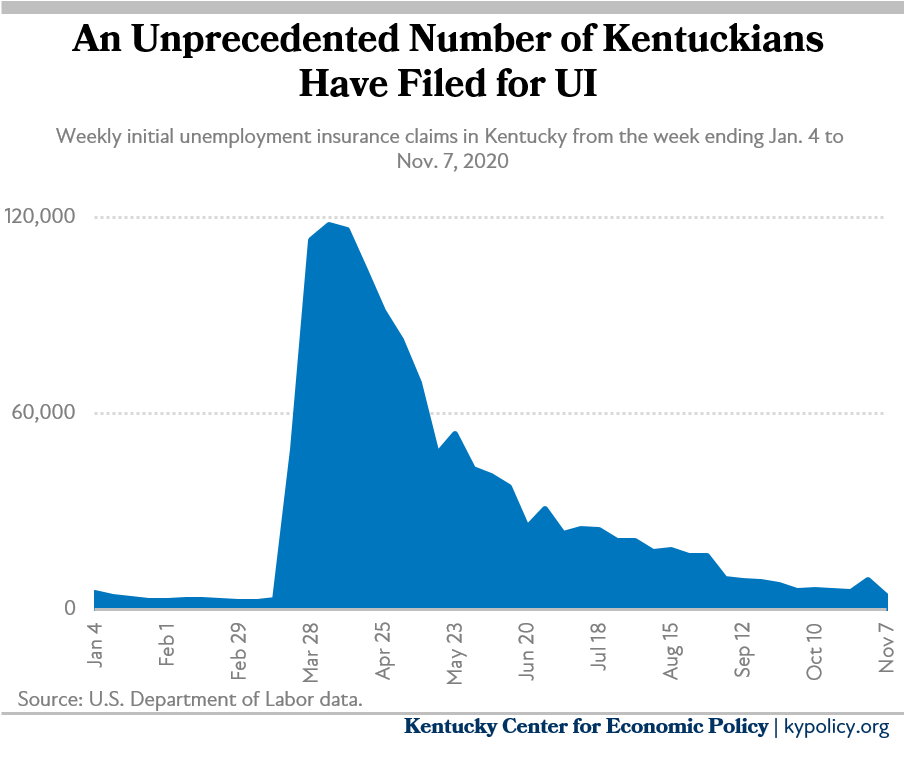

Across the nation, state UI programs and the federal government’s actions to boost aid and expand access to the program have been critical during the economic downturn for both families and the economy. Beginning in March 2020, more than 326,000 Kentucky nonfarm jobs were lost in just two months, and many self-employed workers lost their livelihoods as well, resulting in a massive and unprecedented swell in unemployment claims. Over the course of several months beginning in late March, hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians filed claims. While new claims have only recently receded, real unemployment remains at or exceeding the highest level in the Great Recession. 1

The UI program is counter-cyclical, meaning claims rise during economic downturns, and payments made to laid-off workers are an effective tool for propping up the economy and limiting further layoffs. The more depressed consumer spending is, the greater the impact of UI payments. During the Great Recession, for example, one study showed that for every $100 in UI benefits that claimants spent, an additional $90 in economic activity was generated, and more generous benefit levels yielded higher rates of employment and wage growth.2 Another study showed that between 2008 and 2010, regular state UI payments reduced the decline of the national GDP by 10.5%, and extended federal UI benefits helped reduce the decline of the national GDP by an additional 8.5%. The same report showed states with fewer people who qualified for UI after losing their jobs (like Kentucky) experienced less of a stimulus effect.3

In Kentucky, the regular unemployment insurance program, not including additional recipients and benefits provided by Congress, has paid out nearly $1.4 billion in 2020 through September.4 The federal government has also provided an additional $3.5 billion in emergency, extended and supplemental benefits.5

In addition to protecting the state from more job losses with its counter-cyclical effect, UI has been critical to helping laid-off Kentuckians get by, including workers who are disproportionately low-wage. Those households have far less wealth to fall back on compared to workers with higher incomes.6 And Black workers have less household wealth on average, yet have also been disproportionately laid off on average in this crisis.7 UI is thus an important tool to mitigate growing poverty and inequality in the COVID-19 recession.

Unemployment insurance is modest in Kentucky and most laid-off workers don’t qualify

UI replaces only a portion of the lost wages that result from layoffs.8

In 2019, Kentucky’s UI program replaced a little over half (50.8%) of lost wages on average.9 The average benefit currently is only $281 a week (or $1,204 a month) and the minimum is only $39 a week (or $168 a month).10 These numbers are far below a basic standard of living. For example, a two-parent, two-child household in Mercer County needs to earn an estimated $5,487 per month for a “modest but adequate standard of living” according to the Economic Policy Institute’s Family Budget Calculator.11 Inadequate state benefit levels are the reason the federal government has provided supplemental benefits during the COVID-19 downturn.

Prior to temporary COVID-related expansions in eligibility for jobless benefits at the state level, and a new program at the federal level – Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), which provides benefits for nontraditional employees including the self-employed, independent contractors and others who do not qualify for traditional benefits – most unemployed Kentucky workers did not receive UI benefits at all. As of 2019, fewer than 1 in 5 (19.5%) unemployed Kentucky workers – as determined monthly by the Current Population Survey – qualified for benefits, which was far lower than the national average (27.7%).12

This statistic is referred to as the “recipiency rate.” Kentucky has limited access to benefits for a few reasons, including:

- The way we determine eligibility based on earned income excludes many part-time, temporary and low-wage workers, as well as recent entrants into the labor force. These exclusions fail to reflect the modern economy. More employers are relying on temporary and part-time workers, and more workers must patch together a variety of gigs to support themselves due to a lack of full-time employment opportunities and because they are in school or have caregiving responsibilities.

- The way we determine eligibility based on the circumstances of a worker’s joblessness is very narrow. Unlike a number of other states, Kentucky doesn’t allow benefits for separations due to reasons outside the workplace such as the need to quit due to domestic abuse, compelling family reasons like an illness or disability or the need to relocate with a spouse. Unlike many states, Kentucky also denies benefits to people who are seeking part-time work and workers who need access to training.13

- Also unlike many states, Kentucky doesn’t allow benefits to be used by companies to reduce hours across the workforce while keeping people employed and supplementing a portion of their lost wages with unemployment benefits (a concept known as work sharing).

Restrictions in access to eligibility are especially likely to deny unemployment benefits to women and Black workers, including because of family roles and care responsibilities as well as discriminatory barriers that lead to sporadic work histories and employment patterns.14

In addition to difficulties in qualifying for benefits and inadequate benefit amounts, as part of cost-saving measures in 2017, employees providing in-person assistance to workers filing claims were pulled from 31 centers across Kentucky and concentrated in fewer regional hubs, limiting access to assistance and making it more difficult for Kentuckians without dependable internet access to file a claim.15

According to Census data, in 2019, 16.6% of Kentucky households did not have access to the internet at home.16

Also making benefits more difficult to access – especially during the enormous crush of claims due to the COVID-19 crisis – are the state’s antiquated computer systems. The online interface that Kentuckians use to file unemployment claims is approximately 20 years old, and the technology infrastructure used to collect employer taxes, calculate eligibility and determine benefit amounts is nearly 50 years old, running on an outdated and inflexible programming language called COBOL. Only in 2018 was a funding mechanism set up to accumulate $60 million to update that part of the system with modern software. In March 2020, the state began seeking vendors to replace the system.17

During the Great Recession, all states were eligible for incentive monies to modernize their unemployment insurance systems if they agreed to commonsense improvements to eligibility like those mentioned above (including expanding eligibility to part-time workers, recent entrants to the workforce and people who leave work for compelling personal reasons). Kentucky could have received $90 million to update its UI system.18 However, while 45 states (including DC) made improvements and 39 states made enough changes to eligibility to receive the bonus dollars, Kentucky made no improvements and turned down the much-needed money.19

Kentucky workers have seen benefits reduced while employer taxes remain historically low

During the Great Recession, when the state had to borrow from the federal government to pay unemployment benefits as it is doing now, the General Assembly made cuts to benefits and increases to unemployment taxes to help shore up the unemployment system. Following submission of a report from a task force, the General Assembly enacted legislation in a 2010 special session to generate the funds needed to pay the loan off sooner than would happen under federal law.20

The legislation included the following changes:

- An 8.8% cut to the average weekly benefit amount calculation, moving the weekly benefit from 1.3078% of the total base-period wages to 1.1923%.21

- The introduction of a “waiting week,” essentially a week-long period without benefits for approved claimants (although the benefits for that week are slowly paid to the claimant over the following weeks).

- Slowed growth of the maximum benefit amount that a laid-off employee may receive, pegged to the trust fund balance.

- A gradual increase in the taxable wage base (the portion of annual employee salaries for which unemployment insurance taxes are paid) from $9,000 to $12,000 between 2012 and 2022 (this year the taxable wage base is $10,800).

- An increase in the necessary trust fund balance amount at which employers are able to move to a lower tax schedule.

Because of the cut in the average weekly benefit alone, Kentucky UI claimants have been paid a cumulative $400 million less in benefits since January 1, 2012, when the reduction took effect.22 This estimate does not include the benefits lost for those who were reemployed quickly after being approved for benefits and never received their first week’s payment.

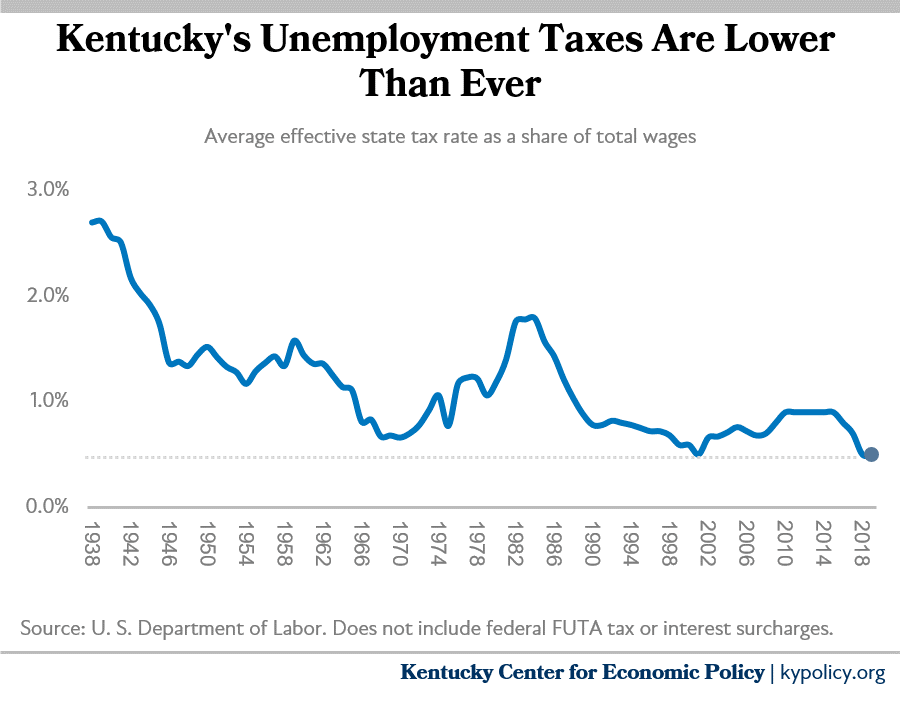

While employees have given up a meaningful share of their benefit for the past eight years, employers’ UI taxes remain historically low. As shown in the graph below, state UI taxes were lower in 2019 than they have ever been going back to 1938 when the program was created, despite the tax adjustments made in 2010. Even after an increase that will automatically go into effect in January because of the impact of COVID-19, the state’s average UI tax rate will remain below where it has been approximately 82% of the time over those 82 years.23 In part, the continued restrictions on eligibility for benefits mentioned above are eroding benefits and therefore lowering the taxes employers pay.

We need to shore up, not weaken, jobless benefits

Unemployment insurance is a powerful anti-recessionary tool and a critical safety net for Kentuckians who are forced to leave their employment. Cutting this already inadequate benefit further through reductions in benefit levels, as was done in 2010, or through shorter benefit timelines or more restrictive eligibility criteria, only hinders the ability of the program to achieve its intended goals while exacerbating hardship for laid-off workers. Recent legislative proposals in 2018 and 2019 proposed reducing the amount or duration of benefits and would have left Kentucky in an even more perilous position in this crisis and families with less to get by on.24

Reducing the amount of UI payments would result in reduced economic activity which can lead to further layoffs – a vicious cycle that is entirely avoidable.

As it stands, Kentucky provides UI to too few unemployed and underemployed Kentuckians, and the benefit amounts many of those workers receive are too small. In particular, we fall behind many other states in the narrowness of eligibility for our program. In order to be better prepared for the next recession, there a number of improvements the General Assembly should make.

Adopt an “Alternative Base Period” (ABP)

Currently, to determine if an unemployed worker has earned enough to qualify for UI benefits, their earnings from the first four of the previous five completed calendar quarters are used.25 That means when looking at a laid-off employee’s work history to determine eligibility and benefits, the most recent period of nearly six months can be completely excluded. This method is a relic from a time when states relied on paper forms from businesses and before computers were widely available (digital systems eliminate the necessity for lag time between employment and eligibility). In states that use an ABP, if the claimant doesn’t qualify under the traditional methodology, the most recently completed quarter is then used as well, which helps to ensure many part-time, low-wage and seasonal workers are eligible.26 By one estimate, having an ABP would allow 1 in 5 workers currently disqualified to qualify, and adopting it only increases the overall UI payouts by 4-6%.27 41 other states have adopted an ABP.28

Broaden the “good cause” definition for leaving employment

Kentucky’s law on good cause reasons for separation is vague and only specifies “lack of work” as a concrete example of good cause that could qualify someone for UI benefits.29 As mentioned before, in practice, only a set of reasons narrowly related to the job (such as lack of work, employment-based harassment, etc.) are considered good cause. The state should broaden this definition to include other compelling reasons for needing to leave a job, regardless of whether the reason is due to conditions specific to the job. For example, good cause could include an individual voluntarily leaving a job to flee a domestic violence situation, following a spouse who must relocate for work or because they must care for a sick loved one long-term or because they have become sick themselves. The state’s narrow definition of good cause is part of why the state recently attempted to claw back benefits from workers who stayed home to care for a loved one with COVID-19, or because they were afraid of contracting COVID-19. After the Great Recession, when the federal government provided incentives to states to modernize their unemployment insurance programs, 32 states adopted at least one of these good causes for separation.30

Implement a work-sharing program

A work-sharing program could reduce layoffs by giving employers an avenue to reduce employee hours with pro-rated UI benefits helping to making up the difference for the lost hours, rather than laying employees off. By keeping workers employed, work-sharing programs can also help businesses retain employees long-term and ease costs on the unemployment system. Earlier this year, as part of a larger COVID-19 response package, the Kentucky state legislature authorized a temporary work-sharing program as 28 other states and Washington D.C. have done, and the state developed regulations for such a program.31 But later, the state withdrew the regulation after learning it would not be fully federally funded due to its temporary status, and the program was never implemented.32

Develop an updated and improved UI benefit application process, and reestablish in-person application assistance when it is safe to do so

The state should move quickly on the March 6 request for proposals to hire a contractor to create and implement a new eligibility determination computer system and a more user-friendly interface. Having a modern program to make eligibility and benefit determinations will also allow the state to make changes rapidly in the future, reducing the kinds of delays that left so many without benefits for months this year.33 In addition, as mentioned previously, the state closed 31 of its 51 offices for in-person help in 2017, leaving just 8 larger “hub” offices and 12 regional offices.34 The General Assembly should fund the return of as many of the in-person UI claim assistance locations as can safely be done during the pandemic, and eventually ensure there is in-person assistance within a reasonable distance for every part of the state.

Make inadequate benefits amounts more reasonable, especially at the bottom and for those with dependents

Kentucky should increase the minimum benefit amount from its current $39 per week. 32 states have a higher minimum, many of which are substantially higher.35 Kentucky should also join four other states and add a dependent allowance for laid-off workers with dependents, in recognition of the added costs of caring for children or ailing parents. These benefits differ from state-to-state, but a reasonable amount should start at $15 extra per week.36

Allow part-time workers to receive benefits while seeking part-time work

For many people before the pandemic, part-time work was a necessity so that they could care for children, parents or other loved ones and because full-time work can be difficult to find. Part-time work has become even more necessary as the pandemic and downturn have led to closed child care centers and required nontraditional instruction for school-aged children. The state should join at least 29 others in allowing unemployed, part-time workers to receive benefits while seeking a new part-time position.37 Doing so would improve gender equity as national data shows women are more likely to work part-time jobs, and to seek out part time work when unemployed.38

Continue paying unemployment benefits to displaced workers in training

Nationally, permanent layoffs are on the rise as industries shed workers without knowing when, or if, they will be able to begin hiring again.39 Many of these workers may need to get new training in order to obtain a new job in the shifting economy. To support them with living expenses until they are able to get a job in a new field, Kentucky should allow laid-off workers in training to receive unemployment benefits as 16 other states have done.40

Prevent claw-backs of unemployment benefits that were mistakenly awarded

During the early days of the pandemic, many unemployed Kentuckians were encouraged to apply for benefits because they were afraid of catching COVID-19 at work, and so they stayed home. After federal guidance came out later contradicting earlier guidance, many Kentuckians were told they would have to pay back some benefits.41 Although the administration has asked for a waiver from the U.S. Department of Labor to not enforce this claw-back, Kentucky should pass legislation banning the practice when UI claimants were following the rules in place at the time.42 Kentucky Senate Republicans have announced plans to introduce legislation to do just that, and it should include future instances as well as the current mistaken overpayment debt.43

Kentucky needs solutions to address immediate issues, and should begin preparing for the next recession now

UI is among the most effective and efficient safety net programs we have because of its dual purpose of supporting individuals and our economy. However, the program needs to be sufficient and effectively administered for it to work as intended. Worker benefits have already been cut in Kentucky and have not been modernized to reflect today’s workforce, even while the systems used to determine eligibility and provide benefits are outdated and difficult to access for claimants and adapt for administrators. In addition to avoiding any further weakening of state UI benefits, Kentucky should learn the lessons of the COVID-19 crisis and make improvements that allow UI to provide the boost our economy needs in times when it needs it most.

- Jason Bailey, “Kentucky Recovery Halted in September, Heightening Need for Much More Federal Aid,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Oct. 15, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-recovery-halted-in-september-heightening-need-for-much-more-federal-aid/.

- Marco Di Maggio and Marir Kermani, “The Importance of Unemployment Insurance as an Economic Stabilizer,” National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2016, https://www.nber.org/papers/w22625.pdf.

- Wayne Vroman, “The Role of Unemployment Insurance as an Automatic Stabilizer During a Recession,” IMPAQ International, July 2010, https://wdr.doleta.gov/research/FullText_Documents/ETAOP2010-10.pdf.

- Data from the U.S. Department of Labor accessed Oct. 5, 2020, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/claimssum.asp.

- U.S. Department of Labor, “Families First Coronavirus Response Act and Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act Funding to States through November 7, 2020,” accessed Nov. 12, 2020, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/docs/cares_act_funding_state.html.

- Julia Menasce Horowitz, Ruth Igielnik and Rakesh Kochhar, “Most Americans Say There Is Too Much Economic Inequality in the U.S., but Fewer than Half Call It a Top Priority,” Pew Research Center, Jan. 9, 2020, https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/01/09/trends-in-income-and-wealth-inequality/.

- Kriston McIntosh et. al, “Examining the Black-white Wealth Gap,” Brookings Institution, Feb. 27, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/02/27/examining-the-black-white-wealth-gap/.Dustin Pugel, “Black Kentucky Workers Are More Likely To Have Been Laid Off in the Pandemic, and Less Likely To Have Been Hired Since,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, September 11, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/black-kentucky-workers-are-more-likely-to-have-been-laid-off-in-the-pandemic-and-less-likely-to-have-been-hired-since/.

-

[1]KRS 341.380 and KRS 341.390.

Between March and July, the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation was meant to replace 100% of lost wages in recognition of the fact that many employees should stay home from work, and that the economy was going to need a significant boost to keep from collapsing. The same concept applies under the Lost Wages Assistance program that President Trump created through an executive order, though replacing less than 100% in many cases. Unemployment Insurance during normal times, when jobs were not as scarce, was designed to help people get by on until they could find another job. - U.S. Department of Labor, “Replace Rates, By State,” Accessed October 21, 2020, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/chartbook.asp.

- U. S. Department of Labor, “Monthly Program and Financial Data,” month ending September 30, 2020, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/claimssum.asp.

- Elise Gould, “The Economic Policy Institute’s Family Budget Calculator,” Economic Policy Institute, Mar. 13, 2018, https://www.epi.org/resources/budget/.

-

U.S. Department of Labor, “Recipiency Rates, By State,” accessed on Oct. 21, 2020, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/Chartbook/a13.asp. Stephen Wandner and Thomas Stengle, “Unemployment Insurance: Measuring Who Receives It,” U.S. Department of Labor, July 1997, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/1997/07/art2full.pdf.

- KRS 341.350 and KRS 341.355. National Employment Law Project, “Modernizing Unemployment Insurance: Federal Incentives Pave the Way for State Reforms,” May 2012, https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/ARRA_UI_Modernization_Report.pdf?nocdn=1.

- Austin Nicholas and Margaret Simms, “Racial and Ethnic Differences in Receipt of Unemployment Insurance Benefits During the Great Recession,” Urban Institute, June 2012, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/25541/412596-Racial-and-Ethnic-Differences-in-Receipt-of-Unemployment-Insurance-Benefits-During-the-Great-Recession.PDF. National Women’s Law Center, “Unemployment Insurance Reforms Important to Women Can Mean More Funding for States,” March 2009, https://nwlc.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/UIModernizationWomenMarch09.pdf.

-

Daniel Desrochers, “State Pulling Workers Out of 31 Unemployment Offices Amid Major Cuts,” Herald Leader, January 10, 2017, https://www.kentucky.com/news/politics-government/article125733614.html. Dean Manning, “Corbin Unemployment Office Won’t Completely Close, State Officials Say,” News Journal, Jan. 11, 2017, https://www.thenewsjournal.net/corbin-unemployment-office-wont-completely-close-state-officials-say/.

- American Community Survey 2019 1 year estimates.

- Jared Bennett, “Effort to Modernize State’s Unemployment Technology Comes Too Late for Pandemic,” Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting, Apr. 14, 2020, https://kycir.org/2020/04/14/effort-to-modernize-states-unemployment-technology-comes-too-late-for-pandemic/.

- Jason Bailey, “Kentucky Will Forego $90 Million for Jobless Workers Unless Unemployment Insurance Updates Made by August,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, February 2, 2011, https://www.kypolicy.us/sites/kcep/files/Unemployment%20Modernization.pdf.

- Michael Leachman and Jennifer Sullivan, “Some States Much Better Prepared Than Others for Recession,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 20, 2020, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/some-states-much-better-prepared-than-others-for-recession#_ftn12. National Employment Law Project, “Modernizing Unemployment Insurance: Federal Incentives Pave the Way for State Reforms,” May 2012, https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/ARRA_UI_Modernization_Report.pdf?nocdn=1.

-

Unemployment Insurance Task Force, “Ensuring Long-Term Stability of Kentucky’s UI System,” January 2010, https://educationcabinet.ky.gov/Reports/Unemployment%20Insurance%20Task%20Force%20Report%20%20-%20January%202010.pdf.

“Early Payoff of $972M Federal Loan Will Save Kentucky Employers Millions in Unemployment Insurance Taxes,” Kentucky New Era, Aug. 10, 2015, https://www.nkytribune.com/2015/08/early-payoff-of-972m-federal-loan-will-save-kentucky-employers-millions-in-unemployment-insurance-taxes/.

- House Bill 5, 2010 Special Session, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/10ss/hb5.html.

- If the benefit calculation hadn’t been reduced from 1.3078% to 1.1923% of base period wages, the accumulated benefits paid to Kentucky workers from Jan. 2012 (when the change took effect) to August 2020 would have been $406.4 million more, using monthly benefit and claims data from the U.S. Department of Labor through September 2020, accessed Oct. 28, 2020, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/claimssum.asp.

- Jason Bailey, Pam Thomas and Dustin Pugel, “How Kentucky Should Spend Remaining Coronavirus Relief Fund Monies,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, September 28, 2020, https://kypolicy.org/how-kentucky-should-spend-remaining-coronavirus-relief-fund-monies/.

-

Dustin Pugel, “Bill Would Limit Unemployment Insurance Benefits and Cut Them Off Much Sooner,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Feb. 3, 2018, https://kypolicy.org/bill-limit-unemployment-insurance-benefits-cut-off-much-sooner/.

Dustin Pugel, “New Bills Would Slash Unemployment Insurance and Leave Kentuckians Stranded,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Feb. 14, 2019, https://kypolicy.org/new-bills-would-slash-unemployment-insurance-and-leave-kentuckians-stranded/.

- KRS. 341.090

- U.S. Department of Labor, “Summary of Findings On the Alternative Base Period,” October 1997, https://oui.doleta.gov/dmstree/misc_papers/misc_research/alternative_base_period/planv1.pdf.

- “What Is an ‘Alternative Base Period’ & Why Does My State Need One?” National Employment Law Project, March 2015, https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Alternative-Base-Period.pdf.

- Annalisa Mastri et. al, “States’ Decisions to Adopt Unemployment Compensation Provisions of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act,” U.S. Department of Labor, Mar. 2, 2016, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/legacy/files/UCP_State_Decisions_to_Adopt.pdf.

- 787 KAR 1:060

- National Employment Law Project, “Modernizing Unemployment Insurance: Federal Incentives Pave the Way for State Reforms.”

- “Work Share Programs,” National Conference of State Legislatures, Accessed Oct. 8, 2020, https://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/work-share-programs.aspx.

- For details about the legislative response to COVID-19, including authorization for the work share program, see 2020 SB 150, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/20rs/sb150.html

- Jared Bennett, “Effort to Modernize State’s Unemployment Technology Comes Too Late for Pandemic.”

- Daniel Desrochers, “State Pulling Workers Out of 31 Unemployment Offices Amid Major Cuts.”

- U. S. Department of Labor, “Significant Provisions of State Unemployment Insurance Laws,” July 2020, https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/content/sigpros/2020-2029/July2020.pdf.

- Maurice Emsellem, Andrew Stettner and Omar Semidey, “The New Congress Proposes $7 Billion in Incentive Payments for States to Modernize the Unemployment Insurance Program,” National Employment Law Project, Jul. 25, 2007, https://s27147.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/UIModActRep.pdf.

- National Employment Law Project, “Modernizing Unemployment Insurance: Federal Incentives Pave the Way for State Reforms.”

- Current Population Survey 2019 annual averages, “Employed and Unemployed Full- and Part-Time Workers By Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity,” accessed on Nov. 5, 2020, https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat08.htm.

- Heidi Shierholz, “Nearly 11% of the Workforce is Out of Work with No Reasonable Chance of Getting Called Back to a Prior Job,” Economic Policy Institute, Jun. 29, 2020, https://www.epi.org/blog/nearly-11-of-the-workforce-is-out-of-work-with-zero-chance-of-getting-called-back-to-a-prior-job/.

- National Employment Law Project, “Question and Answer Unemployment Insurance Modernization: Filling the Gaps in the Unemployment Safety Net While Stimulating the Economy.”

- Jared Bennett, “Gov. Beshear: Save Unemployment Money in Case of Overpayment Debt.”

- Larry Roberts, Buddy Hoskinson and Amy Cubbage, “KY Office of Unemployment Insurance Update: Interim Joint Committee on Economic Development and Workforce Investment,” Kentucky Department of Labor, Oct. 29, 2020, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/313/12900/EDWI-Oct%2029%202020%20Labor%20Cab%20UI%20Update.pptx.

- Jared Bennett, “Legislators To File Bill Preventing Unemployment ‘Overpayment Debt,’” WFPL, Oct. 27, 2020, https://wfpl.org/legislators-to-file-bill-preventing-unemployment-overpayment-debt/#:~:text=Kentucky%20Senate%20Republicans%20intend%20to,they%20discussed%20concerns%20with%20Gov.