Some proponents of HB 475, a constitutional amendment to expand revenue options for local governments, say it will result in localities moving away from occupational taxes and towards sales taxes at the local level. Doing so would be a harmful tax shift that will worsen the upside-down nature of Kentucky’s tax system. Low- and middle-income Kentuckians would pay more in overall taxes while higher-income people would receive a tax cut.

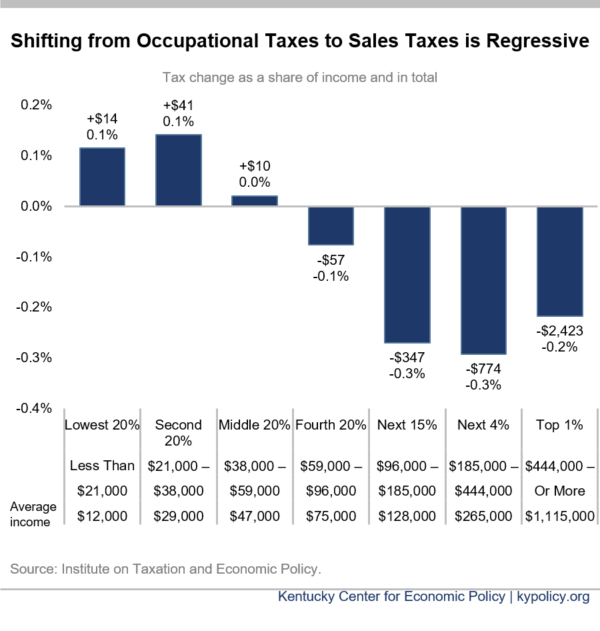

The impact in each community would vary based on what choices are made locally. But analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) estimates that if half of the state shifted from occupational to sales taxes, the poorest 60% of Kentuckians on average would pay between $10 and $41 more a year in taxes while the richest 1% of Kentuckians would receive an average tax cut of $2,423. The graph below illustrates the winners and losers across income groups if such a shift were to occur.

A move to rely more heavily on sales taxes is regressive because low- and moderate-income people spend a larger share of their earnings on items subject to the tax. In fact, many tend to spend practically all of their income to make ends meet, while higher-income people have room to save. Paying sales taxes on necessities, everything from diapers to car repair, is more difficult for those on the bottom than those at the top. In contrast, a payroll tax like the occupational tax asks the same share of wages and salaries for all workers up the income scale.

A move to rely more heavily on sales taxes is regressive because low- and moderate-income people spend a larger share of their earnings on items subject to the tax. In fact, many tend to spend practically all of their income to make ends meet, while higher-income people have room to save. Paying sales taxes on necessities, everything from diapers to car repair, is more difficult for those on the bottom than those at the top. In contrast, a payroll tax like the occupational tax asks the same share of wages and salaries for all workers up the income scale.

Where local sales taxes are imposed would likely make the actual distribution among income groups even worse than ITEP’s state-wide estimate. Local sales taxes will largely benefit wealthier counties that have a significant commercial base at the expense of people living in poorer rural counties who travel to more urban areas to shop. According to one study, local sales taxes hurt struggling communities more than they help wealthy ones. Furthermore, due to the structural barriers they face to economic security, people of color and women are more likely to be at the bottom end of the income distribution and pay more under this tax shift.

Already, Kentucky’s tax system is one in which low- and middle-income people pay a higher share of their income in taxes than do the wealthy. That problem was made worse by state tax changes in 2018 and 2019 that shifted away from income taxes and toward consumption taxes. This shift also weakened revenue growth, resulting in the worst revenue forecast in 25 years for the two-year budget now under consideration in the General Assembly. That is in part because purchasing power for people on the low end of the income distribution grows more slowly in our economy than the incomes of those at the top, resulting in weaker revenue growth.

Local governments in Kentucky certainly need additional revenue. A plan that just shifts who pays local taxes from those who have the most to those who have the least is not the answer.

This analysis was produced by ITEP using their microsimulation tax model, which is described further here, and utilizing Census data from the Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finance.