The Cabinet for Health and Family Services provides health care for Kentuckians in a number of ways, and most funding in its $5.6 billion 2018-2020 budget pays for health care in some form. In the budget agreement from earlier this week, some needed investments were made, but many Kentuckians will be left behind due to chronic underfunding and some additional cuts that compound a decade of public disinvestment.

Budget agreement boosts funding for SCL provider payments

For intellectually and developmentally disabled Kentuckians, Medicaid through the Supports for Community Living (SCL) waiver program gives services to people in their homes rather than in a nursing home or other institutionalized settings. This program allows individuals who prefer to remain in their communities and is helpful to the state as these services typically cost much less than residential care settings ($72,681 vs. $300,225 per year respectively).

The budget compromise provides an additional $10.5 in General Fund monies in order to receive an extra $24.6 million in federal monies in each fiscal year for the SCL program. This money would be used to raise reimbursement rates to SCL service providers who have not seen an increase since 2004, even as costs have risen 27 percent through inflation since that time. The stagnant payment rates have contributed to a 45 percent turnover rate among providers and a 41 percent decrease in services offered to intellectually and developmentally disabled Kentuckians. This funding increase is helpful in retaining providers and improving services through lower turnover. There is also language in the budget bill to encourage state agencies to move dependent Kentuckians with disabilities from institutionalized care to home based care, which is generally less expensive, and use 50 percent of the resulting savings to further increase reimbursements.

New slots for Acquired Brain Injury waiver, but not other programs

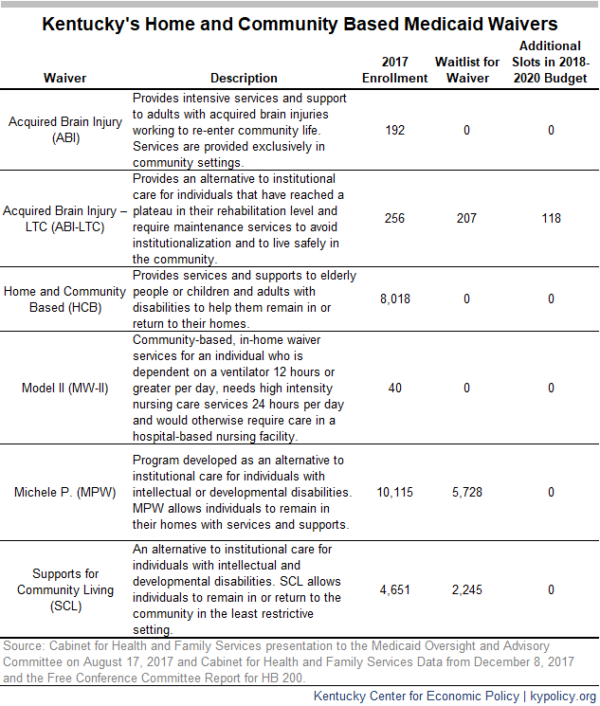

In spite of the long-overdue investment in home and community based services through SCL, the budget compromise does not add waiver slots for new beneficiaries. As of August of last year, 4,651 Kentuckians used these services, but 2,245 were on a waiting list. The Michelle P. waiver, which also provides care for disabled Kentuckians who wish to live in the community, is not appropriated funds for any additional waiver slots. Combined, these two Medicaid programs have waiting lists exceeding 8,000 people – vulnerable Kentuckians who will either be institutionalized, or go without the care available through those waivers into the foreseeable future.

The budget compromise does provide additional funding to increase the number of available waiver slots in the Acquired Brain Injury Long Term Care (ABI-LTC) program. Specifically, it adds $2.6 million in 2020 in General Fund monies to draw down an additional $6.3 million from the federal Medicaid match. This will reduce the waiting list for this program – which consisted of 207 people last August – by 118 people.1

The table below provides a snapshot of Kentucky’s Medicaid waivers, the size of waiting lists and whether the budget proposal alleviates them.

Budget agreement pays KCHIP funding and bureaucratic costs of new Medicaid waiver

The Kentucky Children’s Health Insurance Program (KCHIP) is currently paid for entirely through federal funds due to the Affordable Care Act, and has been since 2016. That enhanced federal match is set to phase out beginning in 2020 when the state will have to kick in 11.5 percent, and eventually return to its normal match by 2021 (the last time Kentucky helped pay for KCHIP the state’s share was 21.04 percent). The final agreement accounts for the 2020 increase by budgeting $12 million to draw down $188 million in federal funds.

The budget agreement also contributes $2.5 million per fiscal year to the Kentucky Pediatric Cancer Research Trust Fund, which will support research at the University of Kentucky and the University of Louisville. This is the first time state funds have been dedicated to pediatric cancer research. Kentucky’s childhood cancer rate his higher than the national average – 42 percent higher for brain cancer specifically.2

The budget includes an increase of $17.5 million in fiscal year 2019 to set up new administrative systems needed to implement the barriers to coverage in the 1115 waiver. These funds will draw down an additional $167.7 million in federal funds, which, when combined, nearly doubles the amount spent on Medicaid administration in one year.

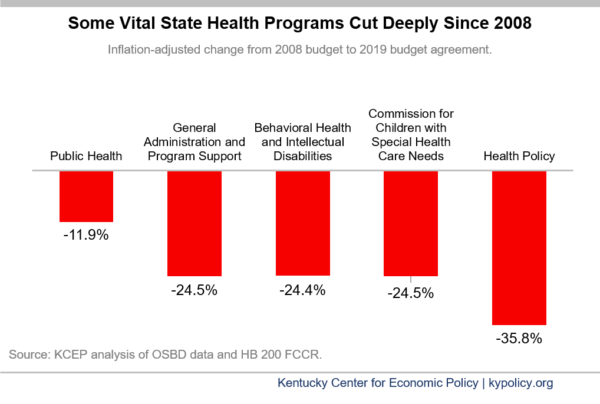

Some health agency budgets slashed in the midst of a decade of underfunding

The Department for Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disabilities, the Department of Income Support and the Commission on Children with Special Health Care Needs were all cut between 5 and 10 percent under the budget agreement compared to their current FY 2018 budgets. When comparing to pre-recession funding levels, the picture gets much worse. After adjusting for inflation, these two departments have had their budgets cut by nearly 25 percent, and the office of Public Health has been cut by over a third.

During testimony to the Budget Review Subcommittee on Health and Family Services this year, each of these groups described their work to help vulnerable children receive life-saving care, provide disabled Kentuckians supports needed to live fuller lives, warn the public about dangerous health threats and provide important data-driven evidence to help shape public policy. Positions have been lost, turnover has risen and capacity has atrophied in each of these departments due to such deep cuts, ultimately hurting the Kentuckians they serve.

Even for agencies that did not receive a direct cut, and those that did, due to changes in assumptions about the pension system, state and local health agencies will have to start contributing more to their employees’ retirement. This is effectively a cut to their operating budget as those larger contributions will come at the cost of other spending within each budget. The possibility of larger pension costs even led some Community Mental Health Centers to question if they could remain open, as was well publicized at the beginning of the year. Health departments will also be strained by the added costs. This large increase in contributions will exacerbate the harm caused by short and long-term underfunding.

- Waiting list for ABI-LTC from a presentation to the Medicaid Oversight and Advisory Committee by the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services, August 17, 2017. ↩

- Childhood cancer rates from testimony by the American Childhood Cancer Organization to the Budget Review Subcommittee on Health and Family Services, January 17, 2018. ↩