Recent enrollment declines in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) in Kentucky and Medicaid in Arkansas due to new work-reporting requirements point to a bleak future for Kentucky’s Medicaid program, which is in the process of implementing its own barriers to coverage.

Kentucky recently decided to allow the SNAP work-reporting requirement to return, which led to nearly 1 in 5 people subject to the requirement losing food assistance. Arkansas’ reporting requirement for Medicaid has resulted in nearly 17,000 people losing coverage. Given that Kentucky’s Medicaid changes are similar to Arkansas’ but even more restrictive, and our own state’s experience with people losing food assistance, it is very likely there will be large Medicaid coverage losses in Kentucky as the changes are implemented.

Arkansas’ Medicaid Changes Have Led to Large Enrollment Losses for Failure to Report Work Hours

Beginning in July of 2018, Arkansas implemented a requirement that Medicaid enrollees report an average of 80 hours a month in a “work activity” or else lose coverage. The requirements are largely based on those for SNAP, meaning Arkansans between ages 19 and 49 years old who do not have a dependent child or a disability must demonstrate through data entry that they are working (or participating in education and training, volunteering, job search, job search training or other work-related activities). Thus far the rule has only applied to people 30-49 years old, but this will change in January 2019 to include those age 19-29. There is a three month grace period for the Medicaid work-reporting requirement, so enrollees could fail to report for one or two months and retain coverage, but would lose Medicaid coverage the third month they failed to adequately report.

Like Kentucky’s plan, there are exemptions that many Arkansans meet automatically, and there are others they can apply for, such as for being a caretaker, “medically frail,” or in alcohol or drug treatment. It is likely that many who were eligible for exemption were not caught automatically and did not request an exemption. Those individuals lost coverage effectively by “falling through the cracks.”

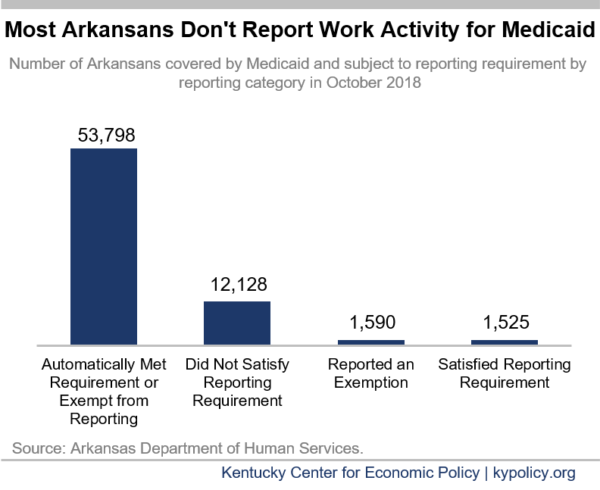

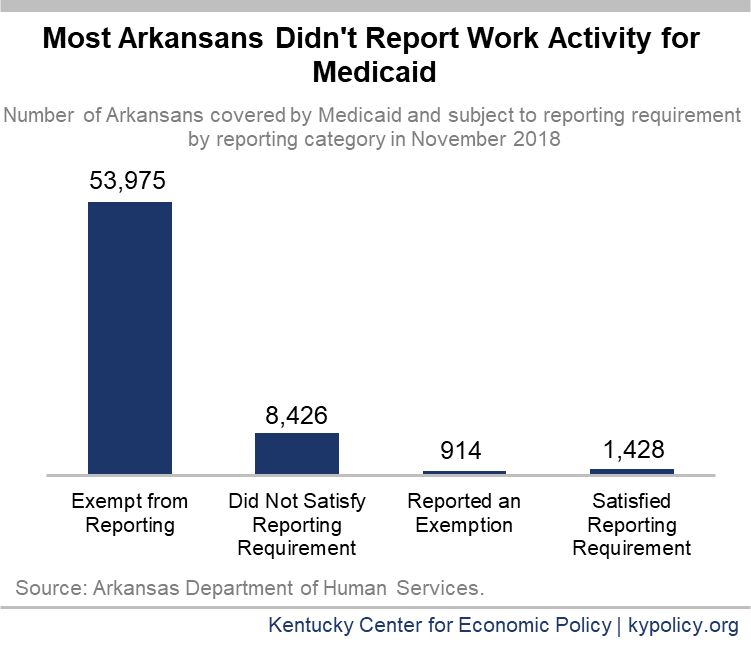

In total, between August and November, 16,932 Arkansans have lost Medicaid coverage for failure to adequately report work hours. As of November, the fourth month for which Arkansas Medicaid enrollees’ coverage was at risk:

- 64,743 Arkansans were subject to the reporting requirement, but 53,975 of them were exempt from actively reporting because they automatically met the requirement (they met a minimum income threshold that serves as a proxy for work hours) or they qualified for some other kind of exemption.

- Of the 10,768 required to actively report something, only 2,342 were able to meet the requirement (914 requested an exemption and 1,428 reported work-related activity)

- Among the remaining 8,426, over half were disenrolled (4,655) and the rest had 1 or 2 strikes against them (2,429 and 1,936 respectively).

- Of the 1,428 who successfully met the reporting requirement, only 371 reported any actual hours at a job.

Although it is not certain that the 16,932 people who have been disenrolled from Medicaid became uninsured, evidence suggests it is unlikely they were able to find coverage elsewhere. The number of low-income Arkansans without Medicaid is almost sure to rise as Arkansans age 19-29 will have to start complying with the requirement to keep coverage starting Jan. 1. Also beginning in January, those who lost coverage for failure to sufficiently report can re-apply for coverage, but it remains to be seen how many will seek to re-enroll at that time.

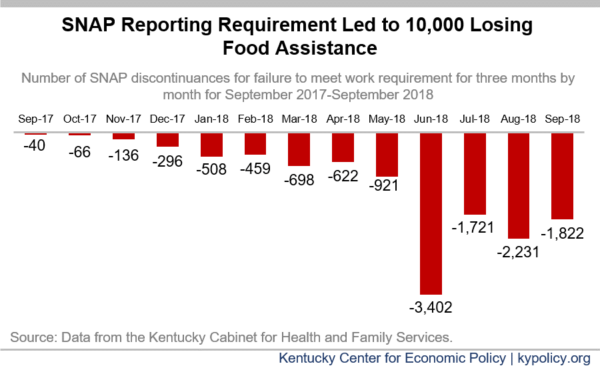

Reinstated SNAP Work Requirement in Kentucky Has Led to 10,000 Losing Food Assistance

Although it is theoretically possible that the harms of a work-reporting requirement in Arkansas are a rare exception, when virtually the same requirements were applied to food assistance participants in Kentucky, they had a similar result. Kentucky’s own experience with these requirements make it hard to ignore the implications from Arkansas.

Between February and May, Kentucky subjected SNAP participants in 92 more counties to a work-reporting requirement (20 counties already had the requirement), resulting in 10,097 people losing food assistance. Similar to the Arkansas requirement for Medicaid, Kentucky SNAP participants who are ages 18-49 and don’t have a dependent or a disability must work an average of 20 hours per week or engage in some kind of work activity in order to keep food assistance. Also like Arkansas, most are exempt from active monthly reporting because their weekly income meets a minimum threshold as a proxy for work hours – how the state normally determines compliance for SNAP. But roughly 1 in 5 people subject to the requirement either did not sufficiently report, or had an insufficient number of hours of work activity and lost food assistance.

Kentucky’s Changes are Likely to Be Worse than Arkansas’ Experience

While Arkansas’ changes are a concerning bellwether for what will happen in Kentucky as a result of our changes to Medicaid, there are several reasons to believe the declines in enrollment will be even more dramatic in the commonwealth. The changes in Kentucky’s Medicaid program will impact a larger number of people and a larger share of those covered by Medicaid. Kentucky’s plan will also include additional ways people can lose coverage.

Kentucky Medicaid covers more people so more is at stake – Whereas Arkansas covers a little over 892,000 people through Medicaid, Kentucky covers over 1.3 million as of August; 462,000 Kentuckians are covered under the expansion, alone. In terms of those whose coverage is at risk, the Urban Institute estimates 330,000 Kentuckians will have to comply with new requirements or else lose coverage, compared to 64,743 in Arkansas.

Kentucky’s requirements affect a broader range of people – Kentuckians age 19-64 will have to comply with the changes, compared to those 19-49 in Arkansas. Also, while 2 parents are exempt from the requirements in Arkansas, Kentucky will only exempt 1 parent per household, which helps explain why the state expects 19,000 fewer traditionally eligible Kentucky adults to be covered because of the changes, as many parents are traditionally eligible for Medicaid.

Kentucky includes more ways to be locked out of coverage – Arkansas’ reporting requirement includes a three-month “grace period” where enrollees can fail to report without losing coverage. Kentucky has no such grace period, and the month they fall behind or fail to report, they will be locked out of coverage for up to six months. Kentucky Medicaid enrollees will also be locked out for six months for failure to verify certain information during their annual redetermination window; for failure to report a change in circumstance that leads to a month of coverage for which an enrollee was not eligible; or if a Medicaid enrollee who earns above the poverty line ($12,140 for an individual) fails to make 2 premium payments.

It is possible for Kentuckians to re-enroll (for each reason except the failure to provide information during the redetermination window). But in Kentucky’s SNAP program – where after having lost benefits for failure to report enough work hours, Kentuckians can re-enroll by simply fulfilling the current month’s required work activity hours – only 34 individuals did so between May and September. Kentucky’s Medicaid changes require much more of enrollees in order to regain coverage, suggesting it is even less likely they will become covered again.

Arkansas Is a Warning for Kentucky

While Arkansas’ restrictions are less harsh than Kentucky’s, it still provides a good glimpse into what we can expect. Much like Kentucky’s waiver, the Arkansas rules provide automatic and requested exemptions, give advance notices to enrollees about the changes and require monthly reporting from enrollees. Also like Arkansas, Kentucky will all but require enrollees to report their work activities or request exemptions online, according to proposed state regulations. The preponderance of the research finds that – regardless of unsubstantiated claims that work-reporting requirements improve individuals’ economic security – such barriers reduce access to economic supports and leave people worse off.

Updated December 18, 2018.