To view the brief in PDF form, click here.

Kentucky has shifted more of the responsibility to pay for health benefits to public sector workers in recent years and then used the savings to help fill holes in the budget. Even after these transfers from the employees’ health plan, its fund balance is continuing to grow, making it a target in the new budget. Governor Bevin’s budget plan includes transferring $500 million out of the plan in 2018 into a new “permanent fund.”

This shift in healthcare costs – also being proposed for participants in Medicaid expansion – has implications for the well-being of Kentucky workers. For public employees, it’s on top of other cuts to their compensation, including a lack of salary increases and pension cuts.

Surpluses growing, leading state to transfer monies from plan

Kentucky operates its own health insurance plan for public employees. The plan covers about 150,000 workers plus their family members (about 260,000 people total). Employees covered include 111,000 active employees and another 39,000 retirees. Of the active employees, 65 percent work for K-12 schools. Another 27 percent work in state government and the remainder include local government, community college and health department employees. In 2015, the plan contributed about $1.4 billion toward the health insurance of employees, making it a major spending category of the state and other public institutions 1.

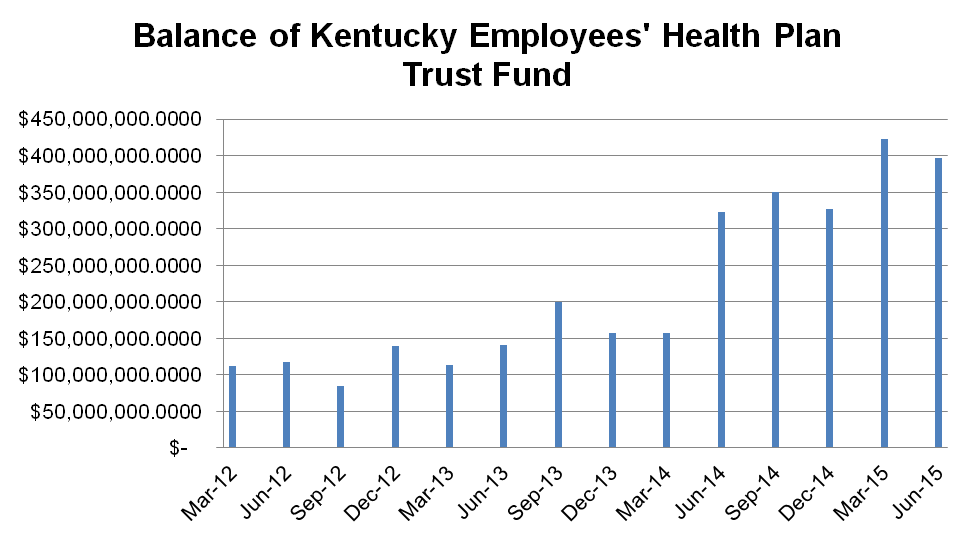

Over a period of years, balances built up in the state’s plan as more was collected in employer and employee contributions than was paid out in claims. In recent years, the state began to transfer those monies to plug other holes in the budget. Kentucky transferred $50 million in 2009 and $93 million in 2015. For budget year 2016, the state will shift another $63.5 million from the plan to the state’s rainy day fund.

However, the plan’s trust fund has continued to grow. It had a balance of $117 million in June 2012 which grew to $397 million by June 2015 (see graph). Approximately $45 million of that balance is in employee account reserves, the $63.5 million transfer is yet to be accounted for and more plan spending tends to happen toward the end of the year as individuals meet their deductibles and out-of-pocket limit 2. According to a story by Tom Loftus in The Courier-Journal, the balance in the fund was $278 million as of September 30. 3

Source: KCEP analysis of KEHP quarterly reports.

Cost shifting plays big role in surpluses

Surpluses are building up in part because of decisions to cut employee benefits and shift more of the cost to workers. For several years, increases in employee premiums played a role in building up that balance. Average monthly premiums rose from $93 on average in 2008 to $144 in 2011, an increase of 55 percent in just 3 years.

More recently, premiums and other contributions have been stable, but the state has passed along costs in the form of higher deductibles and mandated co-insurance. In 2014, the state replaced the old health plans with four new plans that included greater cost sharing. The most popular plan prior to the change had a $370 deductible for individuals, but the two most popular plans after the change had deductibles of $500 to $1,250 for individuals along with co-insurance of 80% to 85% (the more expensive plan also had a Health Reimbursement Account).

This change led to a big decrease in how much the plan is paying out in medical claims. After reaching $1.2 billion in 2013, claims dropped dramatically to $957 million in 2015. That’s a savings of $254 million, or a decline of 21 percent in just 2 years.

Cost shifting plays a role in those dramatic savings. The plan’s per member, per month medical costs decreased 7.7 percent between 2013 and 2014, but the employee’s out of pocket costs went up 33 percent in that period. Between the first six months of 2014 and the same period in 2015 (the latest data available), the plan’s payments per member per month declined 17.7 percent but the employees’ out of pocket contributions declined only 5.4 percent.

The process of shifting health insurance costs to employees has been happening for decades across the public and private sectors. Some argue that requiring employees to have more “skin in the game” will make them better and more selective consumers of health care. But this shift can also lead to trouble paying medical bills for those with lower incomes. And it can mean foregoing needed care because of costs — which can compromise health and result in bigger health costs later as problems worsen when they are not treated early.

In addition, the increased costs can lead to workers skipping employer coverage entirely. The share of Kentucky private sector workers who receive health insurance through their employers has fallen gradually over the decades from 70 percent in 1980-1982 to only 53.7 percent in 2011-2013 4. As a result, a majority of the Kentuckians who have signed up for Medicaid expansion have jobs, they just can’t afford (or aren’t offered) health care through their employers. The workers who have gotten coverage through Medicaid are most commonly employed at restaurants, construction sites and temporary agencies 5.

Cost shift part of decline in public employee compensation

The shift in health care costs to public employees is on top of other cuts to their compensation and problems with the viability of their pension plans. State workers did not receive a raise for four years prior to a one to five percent tiered raise in 2015 and a one percent raise in 2016. Public school teachers and staff received a one percent raise in 2015 and a two percent raise in 2016 after not having increases in several budget cycles. There are no proposed raises to teachers or state employees in the governor’s budget.

Public employee pensions were cut in 2008 and again in 2013. Teachers’ pensions were cut in 2002 and 2008, and they began contributing three percent of their salary for their retiree medical plan after 2010 legislation. Both the public employees’ and teachers’ plans face possible additional cuts this year, and the solvency of the plans is at risk due to years of underfunding.

These challenges threaten to make it harder for Kentucky to attract and retain the workforce it needs to sustain quality schools and other public services. Kentucky public workers make 12.8 percent less in total annual compensation – and 9.2 percent less on an hourly basis – than do comparable workers in the private sector, according to a study by Dr. Jeffrey Keefe for KCEP 6.

House Bill 89, introduced in the 2016 General Assembly, would prohibit transfers from the health plan and require that future surpluses be used to reduce the cost of employee premiums. Another bill, House Bill 37, would allocate these surpluses to the pension plans. Governor Bevin’s plan to create a new fund with $500 million from the plan is a third proposal. The budget language does not specify its use, but comments in the governor’s address and in a story in The Courier-Journal suggest paying pension liabilities as a likely use 7. Control of over use of the funds, however, would lie with the General Assembly in each budget bill.

Implications for Medicaid

This debate over cost shifting also has relevance to Kentucky’s Medicaid expansion. The governor has proposed applying for a waiver that would likely introduce additional cost shifting into Medicaid. Some have mentioned cost savings in the employee health plan as evidence of the success of such “skin in the game” strategies.

But there’s good reason to be even warier of the real savings from cost shifting in Medicaid. While some public employees also have very modest incomes, the incomes of Medicaid recipients are very low – maxing out at about $27,000 for a family of three, for example. Low incomes make people even more price sensitive to the costs of health care. Several decades of research shows introducing premiums and co-pays into state Medicaid programs results in lower coverage rates and less utilization of services 8. That means less care, poorer health and higher health costs later – and the administrative costs of collecting these payments can be higher than the revenue they generate.

- Kentucky Employees’ Health Plan, “Fifteenth Annual Report,” Dec. 14, 2015, https://personnel.ky.gov/KGHIB/Annual%202015%20Report.pdf ↩

- Commonwealth of Kentucky Personnel Cabinet, “2nd Quarter 2015 KEHP Trust Fund Status Report,” https://personnel.ky.gov/KGHIB/2nd%20Quarter%202015.pdf ↩

- Tom Loftus, “Hands off our health fund, state workers demand,” The Courier-Journal, January 25, 2016, http://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/politics/ky-legislature/2016/01/25/hands-off-our-health-fund-state-workers-demand/79294470/ ↩

- Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey March supplement ↩

- Jason Bailey, “Many Kentucky Workers Have Gained Insurance through the Medicaid Expansion, Are at Risk If Program Is Scaled Back,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Nov. 10, 2015, https://kypolicy.org/many-kentucky-workers-have-gained-insurance-through-the-medicaid-expansion-are-at-risk-if-program-is-scaled-back/#fn-3890-3 ↩

- Jeffrey H. Keefe, “Public Versus Private Employee Costs in Kentucky: Comparing Apples to Apples,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, July 2012, http://www.kypolicy.us/sites/kcep/files/Public%20Compensation.pdf ↩

- Tom Loftus, “Bevin’s budget bill contains surprises, details,” The Courier-Journal, January 28, 2016, http://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/politics/ky-legislature/2016/01/28/bevins-budget-bill-contains-surprises-details/79451960/ ↩

- Jessica Schubel and Judith Solomon, “States Can Improve Health Outcomes and Lower Costs in Medicaid Using Existing Flexibility,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 9, 2015, http://www.cbpp.org/research/health/states-can-improve-health-outcomes-and-lower-costs-in-medicaid-using-existing ↩