Kentucky got the good news it has now paid off its $972 million loan from the federal government after the state’s unemployment insurance program fell into the red during the recession. While a recovering economy and additional employer taxes helped pay back the loan two years earlier than expected, so did the fact that Kentucky has restrictive unemployment benefits that have failed to keep up with a changing workforce, limiting the amount that’s paid out to jobless workers in need.

Kentucky’s unemployment insurance costs rose dramatically when job loss spiked in the Great Recession, depleting the state’s trust fund and forcing Kentucky to borrow from the federal government to pay benefits. In part, the state got in trouble because it drained its trust fund even in good times prior to the recession by collecting less in revenue from employers than it paid out in benefits.

In the absence of state action, federal taxes on employers would’ve automatically escalated to pay back the debt. Instead the state passed legislation in 2010 that both cut benefits for workers and raised employer taxes. The state also put in place a temporary employer surcharge in 2012 to pay interest on the federal loan. The cut for workers included reducing the share of lost wages that benefits would replace and adding a waiting week before jobless workers can receive benefits.

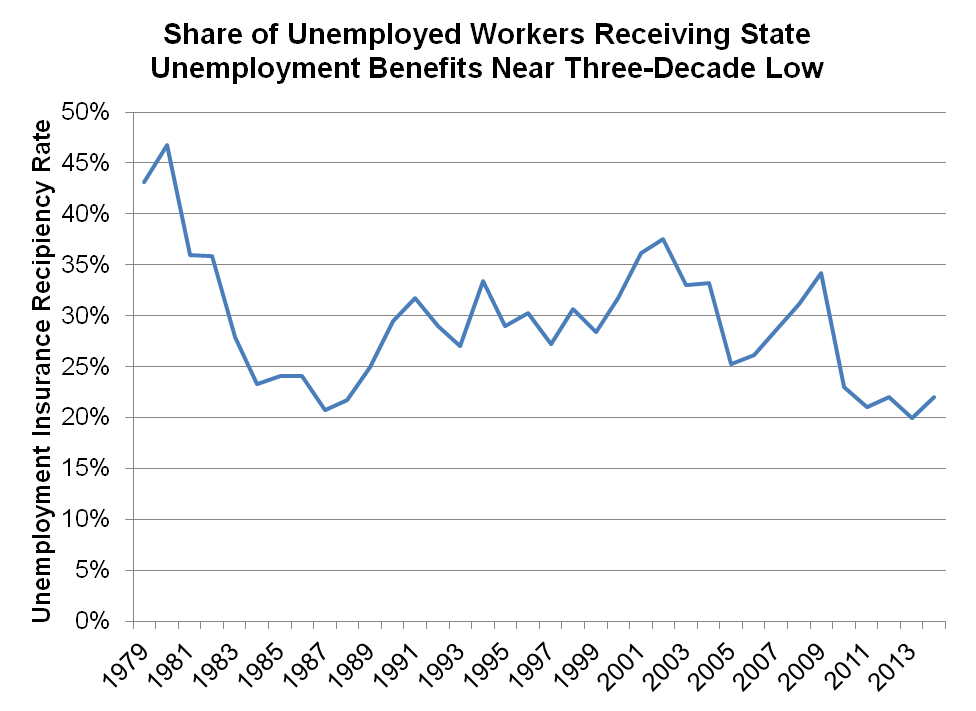

In addition to benefit cuts, tax increases and a growing economy, the state paid off its loan quickly in part because Kentucky workers have limited access to unemployment assistance. Only 22 percent of Kentucky’s jobless workers are actually receiving unemployment benefits, known as the recipiency rate. As shown in the graph below, that rate has hovered recently at its lowest level in three decades.

A bad economy for an extended period is one contributor to this trend, as many workers have run out of the maximum six months of state benefits without finding a job (and now there are no federal benefits that kick in after state benefits end because Congress let the program expire in 2013). But even for short-term unemployed workers, Kentucky’s recipiency rate is low at only 28.1 percent of those unemployed six months or less.

A reason for the low rate is Kentucky’s unwillingness to update its unemployment system to better fit the realities of today’s workforce. Kentucky missed the opportunity earlier this decade to modernize its unemployment insurance system and receive $90 million in federal money for doing so. It was one of only 12 states to turn down the financial incentives for unemployment modernization offered through the Recovery Act. Updates that other states enacted included:

• helping more low-wage workers become eligible by taking into account their most recent 3-6 months of earnings when determining eligibility;

• extending assistance to part-time workers who lose their jobs and are seeking part-time work;

• providing benefits for workers who quit for compelling family reasons including domestic violence or sexual assault or to care for a sick family member;

• offering benefits for long-term unemployed workers who require access to training to improve their skills.

A recent National Employment Law Project report outlines more ways the existing unemployment insurance system is out of step with today’s workforce.

For those who do receive benefits in Kentucky, the payments are very modest. The average benefit is just $294 a week — 33rd among the states — and replaces only 37 percent of the average weekly wage. Kentucky’s maximum benefit is $415 a week, while 30 states have a maximum that ranges higher. Benefits aren’t generous, but they help workers facing tough times and provide a stimulus to the economy just when it needs it most.

The existing state program is on the way to solvency and that’s a great thing. But with a changing reality for workers and another recession inevitable at some point, Kentucky should be having a conversation about how the unemployment insurance system can better help those who lose jobs meet their basic needs and get back on their feet.

Recipiency rate is for Kentucky. Source: U. S. Department of Labor