This week marks the longest period in history the federal government has failed to increase the minimum wage, which has been stuck at $7.25 an hour since 2009. Because Kentucky has not increased its own minimum beyond that same level — unlike 29 other states — wages at the bottom remain stagnant and far too low for Kentuckians to make ends meet.

The last time the Kentucky state minimum wage changed was also in 2009, the year the legislature established a $7.25 an hour minimum. When further action on raising the minimum wage stalled, Louisville created a local minimum at $9 an hour to be fully implemented by 2017, and Lexington followed suit with a $10.10 minimum wage by 2018.

But following a lawsuit by employers, the Kentucky Supreme Court struck down the local ordinances by ruling the General Assembly had asserted its authority to set the state minimum wage and not yet granted that power to localities. That problem could’ve easily been fixed by subsequent legislation giving cities that authority, but the legislature failed to act. Over 76,000 workers would’ve benefitted if the local ordinances were allowed to go into effect.

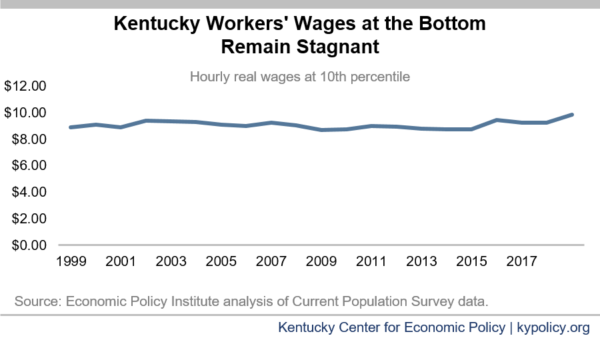

Because needed action has stalled at the state and federal level in recent years, Kentucky wages at the bottom have been flat, as shown in the graph below. In contrast, wage growth was much stronger between 2013 and 2018 in states that increased their minimum wages. A tightening labor market should eventually lift wages if the economic recovery continues, but in Kentucky wages at the 10th percentile are only 5 percent higher than they were in 2001, after adjusting for inflation.

The federal minimum wage has lost 17% of its value since the $7.25 minimum wage was established, and is 31% lower than its peak in 1968 — which was the equivalent of $10.54 an hour today. The current minimum falls far short of ensuring a living wage: For example, a full-time worker at $7.25 an hour makes less than 1/3 of an estimated basic budget for a family of 1 parent and 1 child living in Ashland.

There’s a clear solution to this problem: Congress or the state could raise the minimum wage gradually to $15 an hour, then adjust it for inflation thereafter (we should also pay tipped workers the same minimum wage everyone else makes). Such an increase would provide a direct raise to 533,000 Kentuckians, or 28.7% of the workforce, and an indirect raise to another 159,000 workers. It would also help address the fact that, because of systemic barriers, black Kentucky workers earn just 81 cents for every $1 white workers make, and women earn 86 cents for every $1 men make.