Medicaid is a good deal for Kentucky. Not only does it allow people to receive medical care, it also improves hospital finances, creates jobs, leverages additional dollars from the federal government and grows the economy as a whole. But changes to Medicaid in Kentucky that will reduce enrollment and spending on health care will slow or reverse those economic gains, leaving many communities not only without coverage, but less economically secure.

More Kentuckians Covered Means Fewer Unpaid Medical Bills

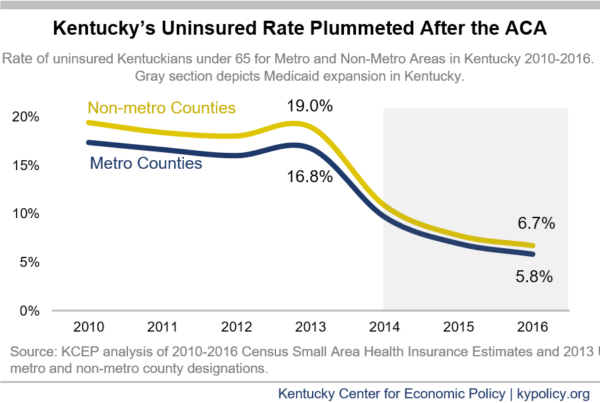

It is well documented that after the Affordable Care Act, mostly thanks to expanded Medicaid eligibility in 2014, Kentucky’s rate of people without insurance plummeted, from 14.9 percent in 2013 to 5.5 percent in 2016. This dramatic decline led the nation, and was true for every part of the state.

Medicaid expansion and the resulting decline in those without insurance improved personal finances. The Urban Institute reported that past-due medical debt in Kentucky dropped from 42.1 percent of adults aged 18-64 in 2012 to 30.9 in 2015, nearly a 27 percent decline. The study also found a close relationship between the past-due medical debt in a given state and the share of uninsured, nationally. According to one recent study, those who lived in states that expanded Medicaid were less likely to incur large amounts of medical debt, have unpaid medical debt, be sent to collections, file for bankruptcy or even incur other forms of harmful debt.

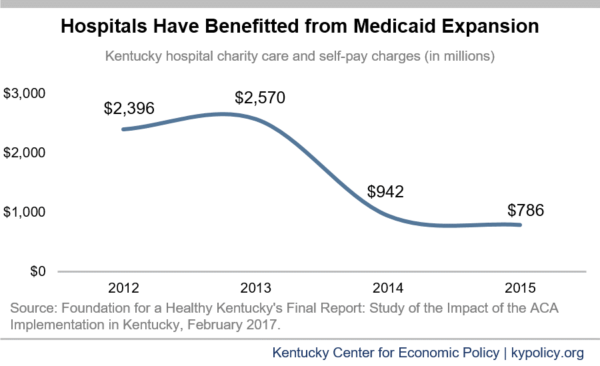

Because more Kentuckians had insurance when they used any kind of health care after 2014, those health care providers, in turn, were paid more often for providing that care. This contributed to a decline in charity care and self-pay charges (which often go unpaid), as seen in the chart below, which meant health care providers had a large increase in revenue and spent much less on debt collection.

In its 2018 annual report to Congress, the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission showed that, as a share of hospital operating costs, uncompensated care in Kentucky dropped 65 percent between 2013 and 2015 – more than any other state.

Health Care Funding Helps Local Economies

When hospitals and other health care providers are better off financially, that money is used to hire more employees, expand facilities and provide a broader array of services. In turn, that increased economic activity filters into the broader economy. While many people get medical care in counties other than where they reside, the map below shows how much Medicaid spent on care for individuals who live in each county.

Kentucky will spend over $11 billion this fiscal year on health care through Medicaid. Of this budget, the state will be responsible for $1.9 billion in General Fund monies, with the federal government paying $8.6 billion – meaning the state leverages 4 federal dollars for every dollar it invests. By 2020, Kentucky’s Medicaid budget is estimated to grow to $11.6 billion — roughly double what was spent in 2013, the year before expansion. That spending ripples throughout the economy in what is known as a multiplier effect; in 2020, every dollar invested through the Medicaid expansion will generate an estimated $1.35 – $1.80 of economic activity in Kentucky. The American Hospital Association estimates that the $12.6 billion in Kentucky hospital expenditures in 2016 generated $25.6 billion in economic output in our economy.

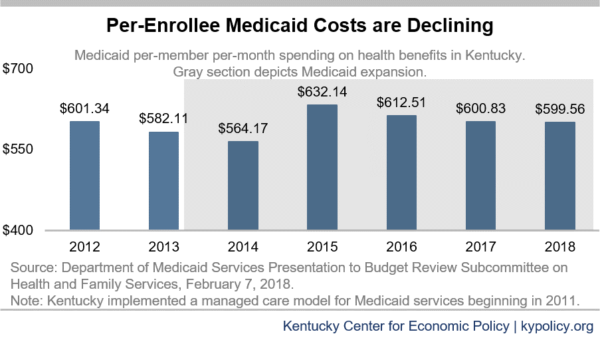

Even while total Medicaid spending has increased over time, the cost to cover individuals on Medicaid has fallen. After an immediate increase in per-enrollee spending post expansion – the result of an initial pent up demand for health services – the cost to deliver benefits on a per-person basis has declined as people’s medical needs were addressed and started to improve.

Health Care Spending in Kentucky Creates Jobs

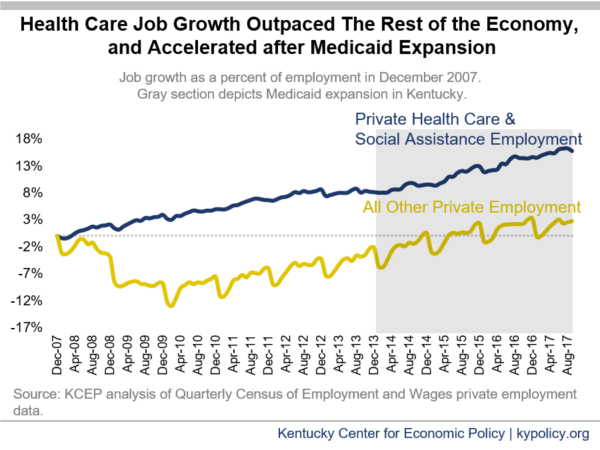

This increase in health care spending has contributed to job growth. While health care and social assistance employment has steadily grown since the recession, it picked up after Kentucky expanded Medicaid. According to Bureau of Labor Statistics data:

- Kentucky added health care jobs through the Great Recession and recovery. The health care and social assistance sector employed 210,300 people in December of 2007, the first month of the Great Recession, and never fell below that number, growing 15.8 percent by September of 2017. The rest of the private sector, however, grew only 2.7 percent, and shrank for two years before growing again. Half of the net job growth from December 2007 to September 2017 came from the health care sector.

- Health care job growth lagged the rest of the private sector pre-expansion. Between April 2010 and December 2013 (the same period pre-expansion as there are data available post-expansion, 45 months), health care jobs grew by 4.3 percent while the rest of the private sector grew by 8.2 percent when Kentucky’s economy began recovering from recession.

- Health care job growth has outpaced the private sector since Medicaid was expanded. Between December 2013 and September 2017, health care and social assistance jobs increased 7.1 percent while the rest of the private labor force grew 5 percent.

This job growth is especially good news because job quality in the sector tends to be higher than others. Wages in health care and social assistance in Kentucky averaged $48,190 in 2017 compared to $45,000 in private sector jobs overall. Furthermore, wage growth in these jobs has been relatively strong; between 2008 and 2017, health care and social assistance wages grew 8.3 while total private sector wages grew just 6.7 percent — $3,680 compared to $2,830 in inflation-adjusted terms. Since 2013, health care wage growth has matched private sector wage growth at 5.4 percent when adjusted by inflation.

The multiplier effect previously mentioned also relates to jobs, with the jobs boost from the Medicaid expansion creating employment outside the health sector as well. One evaluation of the employment benefits of Michigan’s Medicaid expansion estimated that health sector jobs only made up one third of the total employment gains. Harvard research into increases in federal Medicaid spending as a form of fiscal relief to states during the Great Recession found that increases in federal Medicaid funding led to an increase in jobs, 84 percent of which were outside the government, health and education sectors.

Changes to Medicaid Will Reduce Enrollment and Reverse Some Economic Benefits

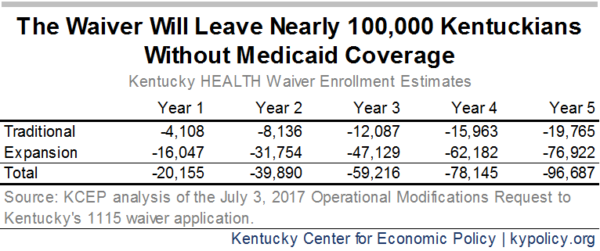

Kentucky will begin adding barriers to coverage among Kentucky’s Medicaid enrollees this year. These changes, such as requiring work activities, premiums, frequent reporting to the state and less flexible re-enrollment will result in an estimated 97,000 fewer adults covered by Medicaid by 2023, the 5th year of the changes. As many as 330,000 Kentuckians’ coverage will be at risk from the work requirement alone according to the Urban Institute.

When Medicaid enrollment is reduced through these new barriers, fewer people will have coverage of any kind. For example, in Indiana where premiums are required of those over the poverty line (just $25,100 for a family of 4) to keep Medicaid, over half of the 60,000 Hoosiers who were kicked off Medicaid or were never enrolled for non-payment of premiums went without coverage of any kind in the first 15 months of the changes.

If Kentucky’s experience matches Indiana’s, economic gains from Medicaid expansion will slow or begin to reverse. Fewer insured Kentuckians will likely lead to an increase in uncompensated care at hospitals and a decline in federal and state funding in local communities. This decline in funding will slow hiring in health care and other sectors of Kentucky’s economy and potentially lead to job losses. The Economic Policy Institute estimated in 2017 that ending Medicaid expansion altogether would cost Kentucky more than 85,000 jobs. Lower rates of employment will suppress demand, further hurting local economies, especially in economically distressed parts of the state where other sectors such as mining and manufacturing have already declined.

Added Barriers to Medicaid will Create Administrative Costs and Inefficiencies

State officials claim the waiver will cause the state to spend less overall because it plans to cover so many fewer people. At the same time, because there are so many new requirements that must be tracked for Medicaid enrollees in Kentucky, the state will have to spend more money to create new and expand existing systems in order to implement those requirements.

Already, Kentucky plans to spend $187 million in administrative costs in fiscal year 2018, with more money budgeted in the next 2 fiscal years. This initial increase in set-up costs is especially high, but with multiple new IT systems to maintain, increased oversight of beneficiaries’ income and work activity and the costs associated with processing a larger churn of enrollees on and off coverage, the administrative burdens and therefore spending will remain significantly higher over the five years of the waiver.

Ultimately, Kentucky’s Medicaid changes will cost more to cover fewer people, and not only will those without coverage suffer, but our state’s budget and economy will, too. Medicaid is a boon to the health care industry and others connected to it – and when Kentucky leverages less federal funding and pays for less health coverage, economic growth, jobs and people’s health will be left behind.