In the wake of last year’s devastating eastern Kentucky floods, the federal government reintroduced a previously defeated proposal to build a new Bureau of Prisons (BOP) prison and “prison camp” in Letcher County. 1 If implemented, the project would add a fourth federal prison to southeastern Kentucky — which already has one of the highest concentrations of federal correctional facilities nationwide — and would direct a nearly $500 million federal investment in prison beds at a time when the region desperately needs substantial investment in flood recovery efforts.

This report is available as a PDF here.

While proponents claim the federal prison project would bring countless economic benefits to Letcher County, research and data do not support this argument. Nearby Clay, Martin and McCreary counties remain among the poorest in the state, and within one of the poorest congressional districts in the nation, despite federal prisons operating in these counties for two to three decades. Eastern Kentucky has the opportunity to improve economically with federal investments that don’t perpetuate the harms of mass incarceration, which already has a vicious hold on Kentucky.

If Kentucky was a country, it would already rank seventh in the world for its incarceration rate, including those in county jails, state prisons and federal prisons.2 The state also incarcerates 40% more people per capita than the U.S. average.3 And the eastern federal judicial district of Kentucky already has more federal prisons than any of the other 93 such districts in the country.4 Adding another federal prison would only further entrench mass incarceration in Kentucky at a time when many places are beginning to reverse course.5

The original discussion of a high-security federal prison in Letcher County formally started in 2006 when Congress authorized a study for the facility. The proposal was approved for a site in Roxanna in 2018, but was withdrawn in 2019 after a lawsuit on behalf by a local landowner, 21 individuals incarcerated in federal prisons, concerned local citizens and other Kentucky residents. The plaintiffs asserted that the prison was unnecessary given BOP’s own projections about a falling prison population, that there would be environmental harms caused by the construction of the proposed prison and that people incarcerated in the prison would be exposed to toxic chemicals from coal extraction that had previously occurred on the land.6

The new iteration of the federal Letcher County prison officially began on Sept. 28, 2022, just months after devastating flooding in the area, when BOP filed a notice of intent to prepare a draft environmental impact statement (EIS) for the facility.7 At a subsequent public meeting in Whitesburg, a representative for Congressman Hal Rogers stated that BOP prisons in three eastern Kentucky counties have had a positive economic impact, “boosting the tax base and strengthening our local workforce,” and that the new BOP proposed prison was an economic opportunity for Letcher County. 8 As of May 2023, the specific site has not been announced nor the EIS submitted.

Three southeastern Kentucky counties already obtained federal prisons, and it did not pay off

Southeastern Kentucky already has three federal prisons, and several more state prisons, but continues to see people move away and remains among the poorest regions in the country.

We examined economic indicators for nearby Clay, Martin and McCreary counties from before and after a federal prison opened in each locality (1992, 2003 and 2004, respectively). Our analysis of county-level economic data shows that rather than economic improvement, longstanding problems have continued or even worsened two to three decades after the federal prisons opened. Total employment has continued to fall, poverty remains among the highest in the country and median household incomes have remained low.

Clay, Martin and McCreary counties have continued to see steep declines in employment and population numbers. Since the respective year each prison was opened, Clay County has seen an approximate 20% drop in number of people employed, Martin County has seen a 43% drop and McCreary County has seen a 14% drop.9 Residents have also continued to move out. Since the prisons opened, Clay County has lost 11% of its population, Martin County has lost 13% and McCreary County has lost 3%.10

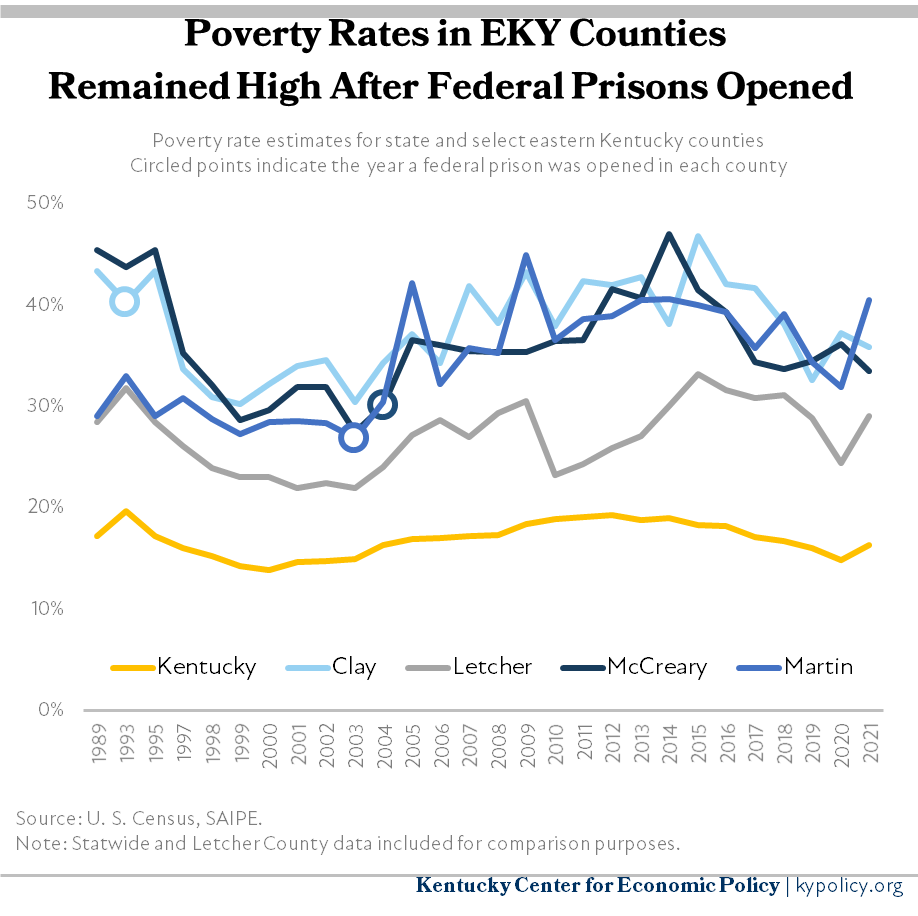

In addition, poverty rates did not improve after the prisons opened. In Martin and McCreary counties, poverty remains high and did not decline after federal prisons opened. Poverty in Clay dropped in the 1990s after its prison opened but that temporary decline was later reversed, mirroring what happened in other counties and statewide during the 1990s.

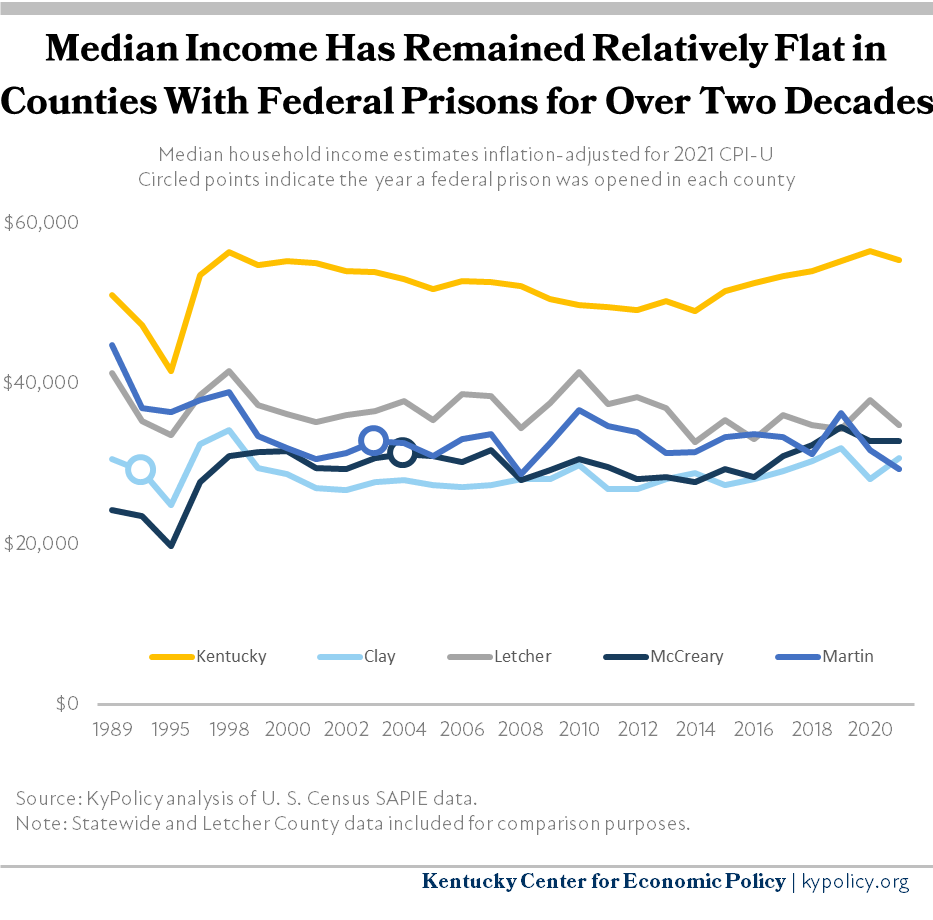

In the period since the prisons were built, median household income has remained relatively flat in Clay, Martin and McCreary counties. Clay County saw a small increase in the 1990s, but so did the other counties that did not build prisons as well as the state as a whole. Median household income in these eastern Kentucky counties has remained very low as well — around $30,000 a year.

In addition, Clay, Martin and McCreary counties remain among the most economically distressed localities in the entire country:

- The poverty rate in Clay County is 35.9%, in Martin County it is 40.5% and in McCreary County it is 33.5%.11

- Of all 3,143 counties in the United States, Martin County is the fifth poorest, Clay County is the 14th poorest and McCreary County is the 32nd poorest.12

- The median household income in Martin County is only $29,387, in Clay County $30,700 and in McCreary County $32,938.13

- Of all 3,143 counties in the United States, Martin County has the eighth-lowest median household income, Clay County has the 15th lowest and McCreary County has the 30th lowest.14

Why have federal prisons failed to spur economic development in these Kentucky counties?

There is a significant amount of literature finding no relation between prison building and positive economic effects, and some evidence that it can actually harm economic development. For example, a study of prison building in central Appalachia found that, although unemployment rates are lower in counties with a prison, per capita incomes are lower and poverty rates are higher.15 A study of rural counties found that in those with low levels of education in particular, such as those in eastern Kentucky, new prisons can do more economic harm than good.16

There are a number of reasons for a lack of economic benefits from new federal prisons. First, many of the jobs from a federal prison come from outside of the community. Federal prisons must be operated with trained staff that is typically brought in from elsewhere. There are significant criteria for BOP employees that many local residents would not meet, including requirements for age, drug testing, credit, and criminal legal system record, as well as education and experience preferences.

The EIS for the original Letcher County prison proposal noted that a significant number of the 300 jobs would be filled by existing Bureau of Prison employees.17 According to the former Judge Executive of McCreary County, five years after that county’s prison opened only 25 to 30 of the 300 people employed at the prison were from the local area.18

In addition to outside, skilled BOP employees, some prison employees commute from other communities. Skilled labor must be hired by federal contractors to build the prison initially, and it is typical for those workers to also come from outside of the community.

Additionally, there are significant local costs accrued by communities operating prisons. Prison building requires local spending on infrastructure, including highways and roads, water and sewer systems, and electricity infrastructure. Taking privately owned land off the local tax rolls also means less money for public schools and local governments. Local community members can end up competing with individuals incarcerated in the federal prison for jobs in the community due to the lower costs of employing incarcerated people for public works and other jobs.

There are also harmful crowd-out effects from prison building, and little to no positive spin-offs. By reducing quality of life and harming the reputation of a community, a prison can make it less attractive to future outside investment or in-migration, and can induce out-migration. Prisons can make communities less attractive for tourism and amenity development that attracts visitors and investment. Prisons lack strong linkages to the local economy, resulting in few positive economic multiplier effects from their operation. There are also opportunity costs associated with investing in a prison, resources that can be better spent elsewhere.

Finally, although prison proponents often describe them as “recession-proof,” in fact relying on prison building is an increasingly risky bet in this political environment. The original Letcher prison proposal was cancelled in part because federal criminal justice reform resulted in a reduced prison population that no longer made it necessary.19 Increased advocacy efforts and actions to reduce the extremely high levels of U.S. mass incarceration raise serious questions about the long-term viability of any new federal prison.

Federal efforts should focus on myriad other needs

Rather than a $500 million investment in a federal prison, eastern Kentucky needs significant investments in flood recovery, in addition to other infrastructure needs and community services and supports — all of which would have a much better economic payoff, including:20

- Providing housing and other supports for people impacted by recent storms21

- Investing in flood resilience and prevention22

- Remediating and reforesting degraded land23

- Funding child care, drug treatment, public health and other needs.

- Federal Bureau of Prisons, “Proposed Federal Correctional Institution and Federal Prison Camp,” Letcher County, Kentucky, https://www.proposed-fci-letchercountyky.com/.

- Emily Widra and Tiana Herring, “States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2021,” Prison Policy Initiative, Sept. 2021, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/global/2021.html.

- Prison Policy Initiative, “Kentucky Profile,” https://www.prisonpolicy.org/profiles/KY.html.

- WEKU, “Rise,” Episode 7, March 30, 2023, https://www.weku.org/podcast/rise/2023-03-30/rise-episode-7.

- Nagzol Ghandnoosh, “Ending 50 Years of Mass Incarceration: Urgent Reform Needed to Protect Future Generations,” The Sentencing Project, Feb. 8, 2023, https://www.sentencingproject.org/policy-brief/ending-50-years-of-mass-incarceration-urgent-reform-needed-to-protect-future-generations.

Carmen Mitchell, Pam Thomas, Ashley Spalding and Dustin Pugel, “In Decade Since Major Criminal Justice Reform, the Kentucky General Assembly Has Passed Six Times as Many Laws Increasing Incarceration as Decreasing It,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Dec. 9, 2021, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-general-assembly-has-passed-six-times-as-many-laws-increasing-incarceration-as-decreasing-it-since-2011/. - Judah Schept, “Coal, Cages, Crisis: The Rise of the Prison Economy in Central Appalachia,” New York University Press, 2022.

- Making Connections News, “Scoping a Letcher County KY Prison,” Dec. 21, 2022, https://www.makingconnectionsnews.org/2022/12/scoping-a-letcher-county-ky-prison/. KyPolicy submitted public comments via email: Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, “Comments re: Economic Implications of Federal Prison Proposal in Letcher County, Kentucky,” Nov. 30, 2022.

- Federal Bureau of Prisons, Scoping Meeting, Letcher County Central High School, Nov. 17, 2022.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey.

- U.S. Census, Kentucky State Data Center population estimates.

- U.S. Census, Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates, 2021.

- U.S. Census, Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates, 2021.

- U.S. Census, Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates, 2021.

- U.S. Census, Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates, 2021.

- Robert Todd Perdue and Kenneth Sanchagrinm, “Imprisoning Appalachia: The Socioeconomic Impacts of Prison Development,” Journal of Appalachian Studies, 22:2, Oct. 2016, 210-223.

- Gregory Hooks, Clayton Mosher, Shaun Genter, Thomas Rotolo and Linda Lobao, “Revisiting the Impact of Prison Building on Job Growth: Education, Incarceration, and County-Level Employment, 1976-2004,” Social Science Quarterly, Jan. 2010, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2010.00690.x.

- Federal Bureau of Prisons, “Final Environmental Impact Statement for Proposed United States Penitentiary and Federal Prison Camp,” Letcher County, Kentucky, July 2015, https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/media/publications/FEIS_For_Proposed_US_Penitentiary_and_Federal_Prison_Camp_July_2015.pdf.

- Sylvia Ryerson, “Speak Your Piece: Prison Progress?,” Daily Yonder, Feb. 20, 2013, https://dailyyonder.com/speak-your-piece-prison-progress/2013/02/20/.

- John Gramlich, “Under Trump, the Federal Prison Population Continued its Recent Decline,” Feb. 17, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/02/17/under-trump-the-federal-prison-population-continued-its-recent-decline/.

- Slyvia Ryerson and Judah Schept, “Eastern Kentucky needs Flood Relief, Not Another Federal Prison,” The New York Times, March 29, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/29/opinion/kentucky-prison-flood.html.

- Jason Bailey, “Flood Relief Legislation Only a First Step, Leaves Out Housing Aid,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Aug. 24, 2022, https://kypolicy.org/eastern-kentucky-flooding-relief-package/.

- Pam Thomas and Jason Bailey, “Kentucky Must Do More to Increase Flood Resilience,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Aug. 15, 2022, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-must-do-more-to-increase-flood-resilience/.

- ReImagine Appalachia, “A New Deal That Works For Us,” April 27, 2021, https://reimagineappalachia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ReImagineAppalachia_Blueprint_042021.pdf.