Labor Day is a good time to reflect on the state of working Kentucky. This year, as the economy continues a long recovery and state and federal decision makers debate policies that could impact progress, it is important to acknowledge we are not yet in a full employment economy that substantially improves Kentuckians’ standard of living.

We have a long way to go to full employment.

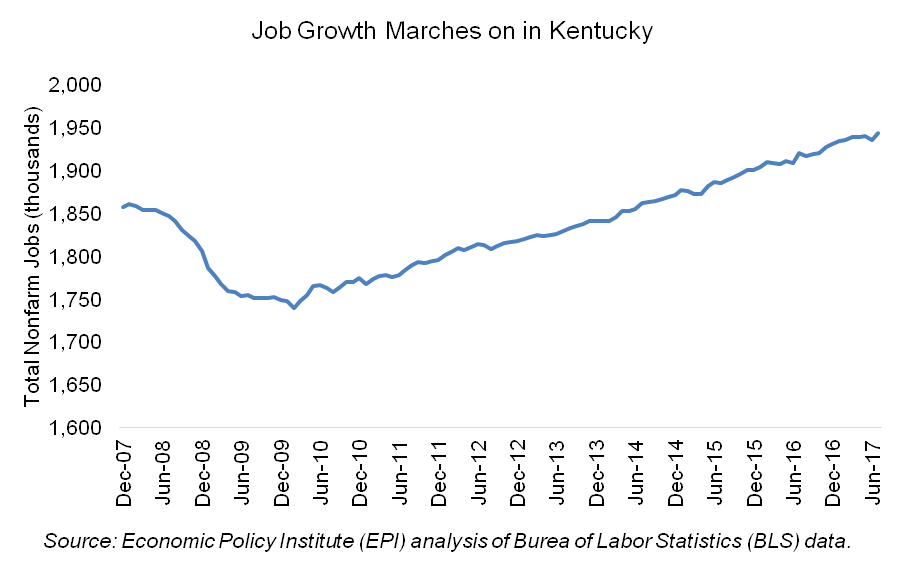

The most recent monthly jobs update from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) shows jobs are continuing to grow steadily in Kentucky as they have been over the 7.5-year period since the recovery began – by 11.8 percent since the trough of the recession in February of 2010. Growth is positive but the pace is moderate and, despite political rhetoric, has not accelerated in 2017.

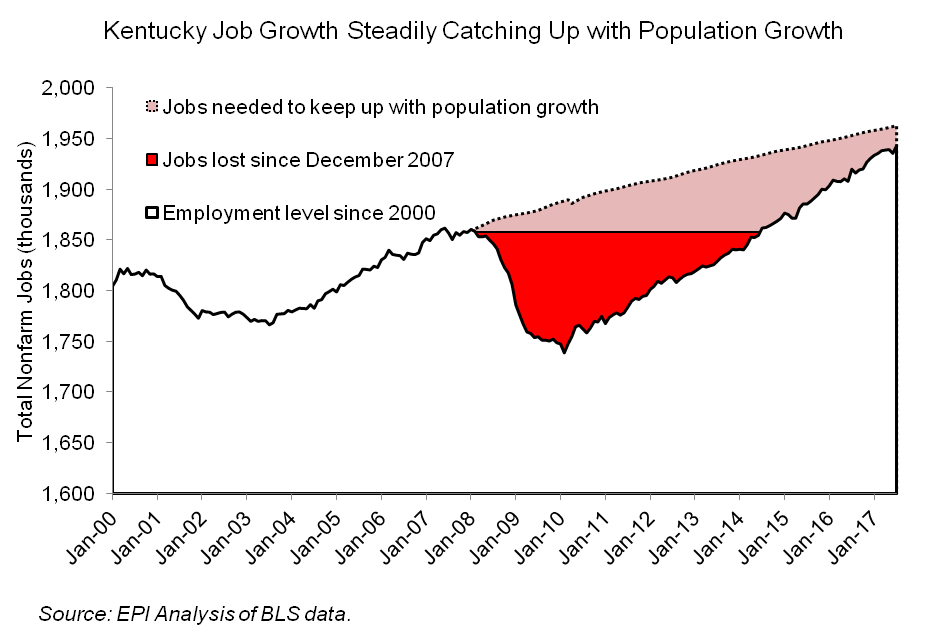

Even with this steady growth over many years, the labor market has not yet closed the gap between actual job growth and what is needed to catch up with population growth in the civilian non-institutional population over age 16 since the Great Recession (see graph below). Kentuckians still face a gap of 19,000 jobs compared to employment levels in December of 2007, once population growth over that span of time is factored in.

An even more sobering comparison – employment today versus the last time Kentucky and the nation experienced full employment in the early 2000s – reveals there is still much room for improvement. If the same share of the civilian, non-institutional, prime-age population (limited to ages 25-54 to remove distortion caused by aging baby boomers) had been employed in 2016 as were employed in 2000 (78.2 percent instead of just 73.6 percent), 77,000 more Kentuckians would have had employment in 2016.

Unemployment in Kentucky provides further evidence of remaining slack in the labor market. The unemployment rate has mostly held steady over the last 2 years – from 5.2 percent in July of 2015 to 5.3 percent in July of 2017, meaning the share of the labor force in search of work has not declined. On a more positive note, labor force participation rose from a low of 56.9 percent to 59.5 percent as previously discouraged workers began actively searching for employment again.

The continuing shortage of jobs produces weak wage growth.

The public discourse about Kentucky’s labor market challenges often assumes the main problem is with workers (their willingness to work, skills, job readiness, etc.) and not the opportunities available to them – that we face a shortage of willing, productive workers instead of a shortage of good jobs. One way to test this assumption is to measure wage growth: When labor markets are tight and employers must compete for employees, a primary strategy for filling vacancies is to improve compensation.

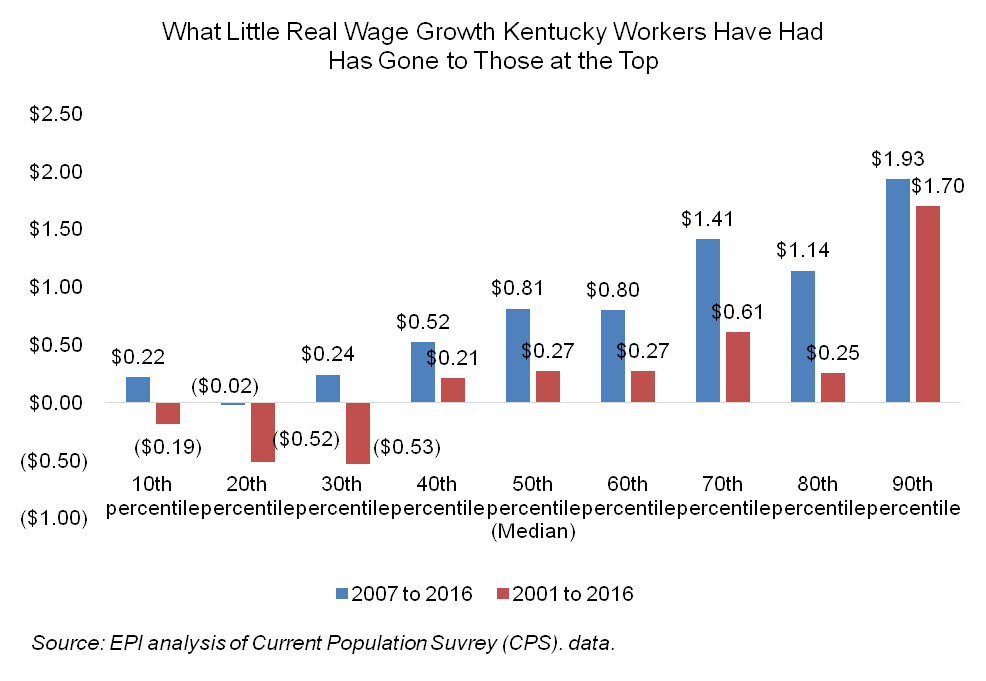

In Kentucky, unimpressive wage growth hardly suggests that in today’s economy employers are making greater effort to attract skilled workers, while it also reflects the fact a large share of job growth is coming from industries providing low-quality jobs. Wage growth adjusted for inflation has been tepid and mostly isolated to the top end of the wage distribution (see graph below). Typical workers at the median have hardly seen their wages grow at all over the last 15 years, while workers in the bottom 3 deciles are mostly worse off than they were in either 2007 or 2001.

At median wages in 2016 ($16.73 per hour), a full-time, year-round worker in Kentucky made $34,798 annually – too little to support a “modest yet adequate” lifestyle for one adult and one dependent even in rural Kentucky. And though real wages were up a slight $0.42 for workers at the median compared to 2015, for workers at all other deciles that year wages either fell or stagnated.

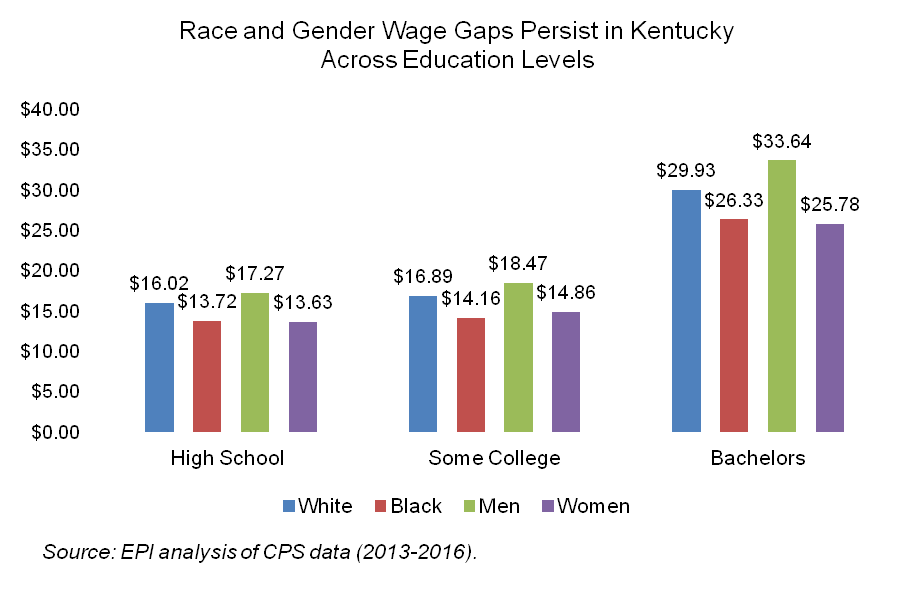

The figures examined so far are aggregate: They look at how the labor market in Kentucky is for all workers. But economic expansions take longer to reach some groups such as young workers and people of color, meaning they face disproportionally poor outcomes. For instance, the graph below shows that even at similar levels of education, black Kentuckians and women make less. Full employment as a policy goal, along with other policy solutions aimed at improving job quality and reducing inequities, is essential to help raise standards of living for all Kentuckians.

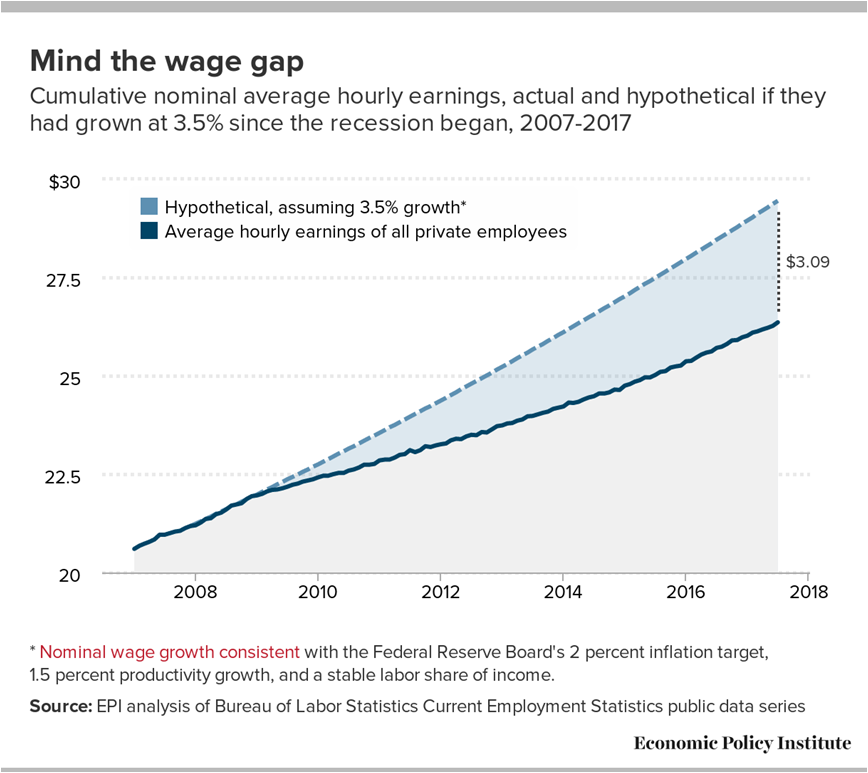

Decisions made at the federal level about monetary policy fundamentally affect Kentucky’s economy. Though the Federal Reserve has begun moderating expansive monetary policy, national data show nominal wage growth is still below what would indicate a full recovery. EPI quantifies the gap between how much nominal average hourly earnings have grown since just 2007 and how much they would have grown if on target as an additional $3.09.

Policy should support continued economic expansion and give workers a raise.

Tightening the reigns on monetary policy before the economy is at full steam would stifle job growth that is still badly needed to reach all groups of workers and put upward pressure on wages in Kentucky. But there are other ways policymakers can either help or hinder on the path to a full recovery.

- Strengthening public investments in Kentucky communities at both the federal and state level would put people to work and help build the foundations of long-term economic growth. Direct spending on infrastructure and education are two prime examples with big payoffs. Investments can also be targeted to communities left behind by the recovery, where in many cases there are fewer jobs than before the recession.

- Cutting investments in Kentucky, on the other hand, will stifle our short-term recovery and hurt long-term growth. For instance, recent efforts in Congress to repeal the Affordable Care Act and slash Medicaid would cost thousands of jobs, worsen the health of our labor force and weaken local economies. Similarly, the assertion that hundreds of millions will need to be cut from essential public investments to pay for Kentucky’s pension systems would harm the economy and weaken the foundation for growth over time. In addition, using spending cuts to pay for new or continued giant tax breaks for the wealthy is a poor strategy for economic growth.

- Giving Kentuckians a raise through a higher minimum wage would put money into workers’ pockets and into circulation in our local economies. Unlike Kentucky, 29 states and D.C. now have a higher minimum wage than the federal $7.25, and 40 localities have higher minimum wages than their states’. Other needed policy changes such as fair scheduling, a higher overtime threshold and paid family and sick leave would similarly improve job quality where the market fails to do so.

- For the same reason putting more money into workers’ pockets helps the economy, taking money out of retirees’ pockets through draconian pension changes will hurt our recovery, especially in communities where schools and other public entities employ a large share of the workforce. Similarly, lawmakers should avoid passing additional anti-worker legislation that, like the prevailing wage repeal and enactment of right-to-work in 2017, reduces worker pay without the benefits advocates claim.

The benchmark for how well we’re doing this Labor Day should ultimately be workers’ standard of living. With the sense among many Kentuckians that they are no better off — or perhaps even worse off than just a couple decades ago — we’ve got our work cut out for us.