Despite improvement, the labor market is still weak for young Kentuckians graduating from high school and college in 2016 according to a new report from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI). These graduates join the previous seven classes who have faced “profound weakness” following the Great Recession.

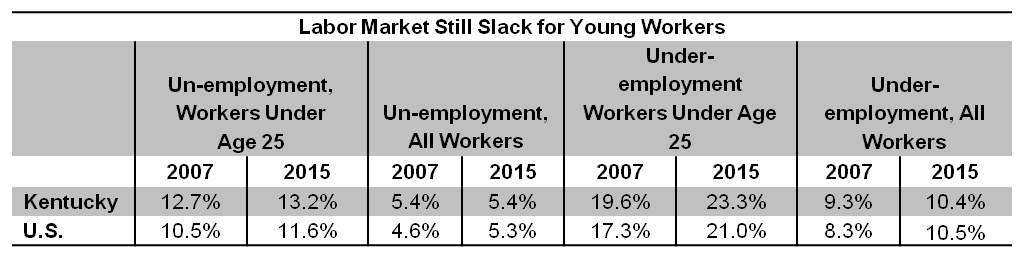

In 2015, the unemployment rate for workers under age 25 in Kentucky was still 0.5 percentage points higher than before the recession (unemployment includes people who are currently without work, but actively seeking a job). Even more indicative of the extent of labor market weakness, the underemployment rate for young Kentuckians is 23.3 percent and still 3.7 percentage points above the 2007 rate (underemployment includes the unemployed and also those who are employed part-time but would rather have full-time work and those who have given up looking for work in the last four weeks but have actively looked in the past year). In contrast, the 2015 unemployment rate for all Kentucky workers was back down to its prerecession level and underemployment was elevated just 1.1 percentage points.

Notes: Includes all workers age 16 and older. Click here to compare rates across states.

Source: EPI analysis of CPS Microdata.

Young workers face competition from older, more experienced workers in a strong economy and their employment prospects are hurt disproportionately in hard times. The depth and length of the trouble for young workers since 2007, EPI points out, is not due to some unique characteristic of young people today – such as a lack of education – but to the historical severity of the Great Recession and the slowness of the recovery.

In fact, Kentuckians “are more educated than ever.” Yet many educated young people are working in jobs that do not require a college degree – nationally, 44.6 percent of college graduates under 27 were in this predicament in 2015. That’s up from 38 percent in 2007.

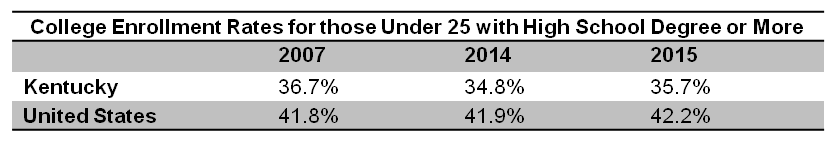

Despite these unfavorable conditions, it’s not true that young people today are taking refuge from the recession in large numbers by returning to school. Enrollment at Kentucky’s universities and community colleges jumped from 211,179 in 2008 to 235,833 in 2011, but had fallen back to 208,251 by 2015. As the table below shows, a smaller share of young Kentuckians were enrolled in 2013-14 and 2014-15 than before the recession. Nationally, EPI notes, enrollment growth is in line with long-term historical trends and does not indicate that young people are attempting to “ride out” the weak employment situation in school. Combined with the lack of employment, that means an elevated share of young people are “idled” by the bad economy—neither working nor in school.

Source: EPI analysis of CPS Microdata.

One possible explanation for why postsecondary enrollment isn’t higher is that decreased public investment in higher education over recent decades has led institutions to raise tuition. With generally stagnant wages over the last 15 years that have only recently returned to 2007 levels, the money people have to pay for college has not kept up with the cost. And while other states have begun reinvesting in higher education after deep cuts through the recession, Kentucky continues to cut state funding including in the new 2017-18 budget.

Young people who do manage to get through college are graduating with more debt. Nationally, average debt has tripled since 1989 according to EPI. In a slack labor market, with fewer (and lower-quality) jobs and stagnant wages, repayment is more difficult. Kentucky students have the third-highest student loan default rate in the nation.

Overall data for the graduating class of 2016 show reason for continued concern, but disaggregated data by race/ethnicity reveal that young black and Hispanic workers face even deeper challenges in the labor market. Nationally, today’s unemployment rate for black college graduates is still 0.4 percentage points higher than peak unemployment was for white graduates during the recession (9.4 percent compared to 9 percent). The current unemployment rate for white college graduates is 4.7 percent. Unemployment is also higher for black high school grads than their white peers. For Hispanic high school and college grads, unemployment rates tend to be higher than for white but lower than for black graduates.

And while women have tended to fare better in the recession in terms of employment – due in part to the fact that traditionally male-held jobs in manufacturing, construction and transportation are hit harder by recessions – women college grads make 79 cents on the dollar what men do. The pay disparity among high school grads is smaller (92 cents on the collar) and has actually shrunk since 2000, possibly due in part to state minimum wage increases which disproportionately benefit women who make up a larger share of the low-wage workforce.

Young Kentuckians will suffer the consequences of the weak labor market they are entering for some time to come. EPI lists two main types of federal and state policies that would tighten the labor market for all Americans, including young people: 1) policies that move the country toward full employment such as continued low federal interest rates and state and federal investments in infrastructure and 2) those that put more money in workers’ pockets like raising the minimum wage, strengthening the EITC, protecting collective bargaining, ending discriminatory practices and raising the overtime threshold.