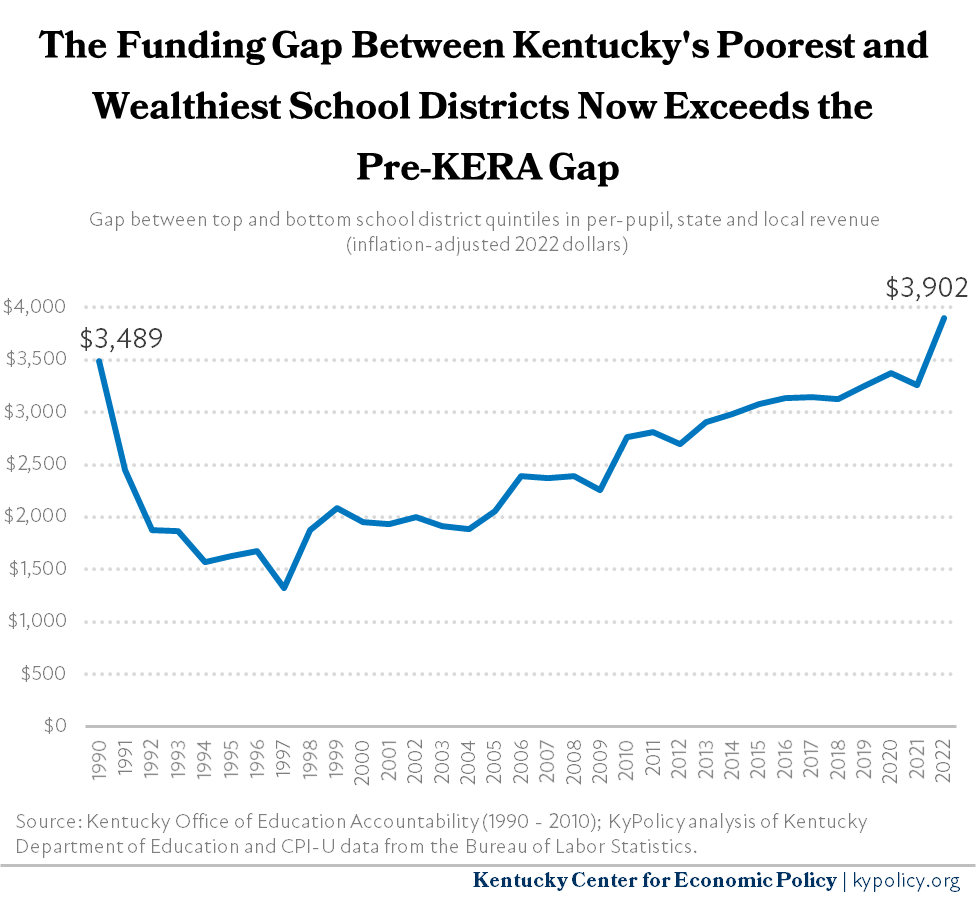

The difference in per-pupil funding between the state’s poorest and wealthiest districts now exceeds the level deemed unconstitutional by the Kentucky Supreme Court more than three decades ago. In 1990, there was a $3,489 per-pupil funding gap, in 2022 dollars, between the wealthiest and poorest school districts. In 2022, the per-pupil gap reached $3,902.

This “equity gap” shrank dramatically after 1990 in the wake of historic tax increases to better fund education and a new system of more equitable school finance contained in the Kentucky Education Reform Act (KERA). But soon after, the trend began to gradually reverse due to inadequate state appropriations for K-12 education and tax breaks that reduced state revenues.

Now, over three decades after Kentucky’s landmark effort to create more equity in education across the commonwealth, that progress has been erased, leaving many thousands of students without the resources they need to get the equal education they deserve. In fact, poorer school districts are arguably even further behind the wealthiest ones than they were prior to the lawsuit that resulted in KERA’s passage.

In 1989, in Rose v. Council for Better Education, the Kentucky Supreme Court held that the state had failed in its duty, set forth in Section 183 of the Constitution of Kentucky, to “provide for an efficient system of common schools.”1 One of the central tenets of the Rose decision was that the General Assembly must “provide equal educational opportunities to all Kentucky children.” The court explained:

The system of common schools must be adequately funded to achieve its goals… [and] must be substantially uniform throughout the state. Each child, every child, in this Commonwealth must be provided with an equal opportunity to have an adequate education. Equality is the key word here. The children of the poor and the children of the rich, the children who live in the poor districts and the children who live in the rich districts must be given the same opportunity and access to an adequate education. This obligation cannot be shifted to local counties and local school districts.

KERA established the Office of Education Accountability (OEA) and charged it with monitoring funding equity among school districts, in addition to other responsibilities. OEA prepared and submitted a School Finance Report each year between 1992 and 2006, with the analysis going back to 1990. In 2006, the General Assembly amended the law to require the report only upon request by the legislative Education Assessment and Accountability Review Subcommittee.2 Since then, OEA produced one report with analysis through 2010, which was presented to the subcommittee in 2012.3 OEA also updated their calculations for only the 2020 fiscal year as part of a larger report presented to a special school funding task force established by the General Assembly and the Education Assessment and Accountability Subcommittee in 2021.4

This KyPolicy report updates the analysis for all years through 2022, focusing on one key application of OEA’s quintile-based method – measuring the per-pupil state and local funding gap between the school districts with the highest and lowest property assessment values, with each quintile including as closely as possible 20% of the student population. By this measure, Kentucky’s education funding is less equitable than it was in 1990.

In the Rose decision, the Supreme Court of Kentucky specifically interpreted the constitution’s imperative that the state provide an “efficient” system of common schools as requiring funding that is both adequate and equitable. This updated analysis only addresses whether the General Assembly’s funding is equitable, but does not attempt to address its adequacy.5

Kentucky’s education resource gap has now exceeded pre-KERA levels

OEA has historically used a quintile-based analysis to examine the level of funding equity among school districts. As the graph below illustrates, the gap between the top and bottom quintiles in 2022 dollars is now above the level it was before KERA. In current dollars, the gap in state and local funding between students in the top and bottom quintiles in 2022 was $3,902 – $413 or 11.9% greater than in 1990.6

The equity gap including so-called “on-behalf funds” has also been widening. These substantial state resources – $1.9 billion in 2022 – include the employer portion of teacher retirement, health and life insurance as well as technology and debt service costs.7 On-behalf funds are not included in the graph above in part because they have been reported inconsistently since 1990. Additionally, a significant portion of these dollars currently are employer pension contributions that do not go to schools or teachers but go to pay back retirement system pension liabilities created primarily by past General Assemblies’ decisions to not make the actuarially determined contributions for benefits.8

But even including on-behalf funds using KDE data available more recently and OEA’s 2012 analysis does not narrow the equity gap in real dollars – it actually widens it. That is because pension contributions are set as a percentage of salary and are therefore higher in wealthier districts that pay higher teacher salaries. For example, Fayette County and Jefferson County “receive” 24.6% of on-behalf payments but only 13.4% of other state contributions (though again, a large portion of these funds go to the retirement system to rebuild its balances rather than to teachers or schools). The total state and local per-pupil funding gap between the 1st and 5th quintiles grows over time when on-behalf funds are included – from $2,530 in 2010 according to OEA to $4,562 in 2022 (both figures in 2022 dollars).

Another way of determining how much further behind the poorest districts are from the wealthiest ones is to consider the size of the gap as a percent of the total funding for the bottom quintile of districts. Under this metric, the inequity does not surpass pre-KERA levels but is still higher than at any time since the year KERA was enacted. In 1990, the inflation-adjusted gap in funding between the top and bottom quintiles ($3,489) was equal to 58% of state and local funds for the bottom quintile ($5,967). That share fell to 14% by 1997 but has been creeping back up since. In 2022, the gap ($3,902) is 42% of the bottom quintile’s state and local per-pupil revenue ($9,332).

Mechanisms that improved school equity under KERA rely on adequate state funding

In Rose v. Council for Better Education, the Kentucky Supreme Court was clear that achieving equity would require additional revenue. The General Assembly could not just reallocate already inadequate resources. In 1990, legislators responded by passing KERA, which, in addition to reforming academic expectations, performance measurement, local decision-making, teacher development, oversight and accountability, wraparound services for students and more, improved funding adequacy and equity.9 The new core funding formula, Support Education Excellence in Kentucky (SEEK), guaranteed a minimum amount of funding per student and established a formula that divides the responsibility between school districts and the state, taking into account district property wealth, or lack thereof.

Through state level tax changes, the legislature raised an estimated $1.3 billion in new revenues for the General Fund over two years, with the vast majority going to education (SEEK and non-SEEK).10 These measures included, in order of the amount of revenue they generated:

- Getting rid of several individual income tax deductions by conforming to the federal tax code, as well as eliminating the large state deduction for federal income taxes paid.

- Increasing the sales tax rate from 5% to 6%.

- Increasing corporate income tax rates by one percentage point, bringing the top rate to 8.25% (it is 5% today).11

Under the KERA funding formula, local districts are required to levy, through a combination of property, motor vehicle and permissive taxes, a minimum of 30 cents per 100 dollars of assessed property to participate in the SEEK program.12 SEEK funds are distributed on a per-pupil basis, as determined by the adjusted average daily attendance, and the amount generated locally is equalized by the state to match the guaranteed SEEK base, which is established by the General Assembly in the biennial budget.13 This formula means local districts with the wealth to generate more revenue receive fewer state dollars, while poorer districts with less capacity to generate revenue receive more from the state.

Local districts also have the authority to:

- Generate an additional 15% of the adjusted SEEK base, otherwise known as Tier I funding, which the state partially equalizes. The tax rate that generates Tier I funding, referred to as the “HB 940” rate, is established considering revenues from other permissible taxes levied by the school district. No portion is subject to voter recall. Absent these KERA provisions, school districts would be subject to voter recall on the portion of any levied property tax rate that generates more than 4% real property revenue growth over the prior year.14

- Generate up to 30% of the adjusted SEEK base, plus Tier I, subject to a voter approval. Amounts generated through this levy are referred to as “Tier II” revenues, and are not equalized by the state. Tier II was established to set an upper limit on local effort, although there are some districts – due to grandfathering and anomalies that occur because of the interaction with other tax provisions – that currently levy a rate exceeding the Tier II upper limit.15

In theory, the shared responsibility between the state and local school districts should provide an adequate baseline of funding for all school districts, while allowing local communities, within limits, to exceed the baseline. In reality, the lack of meaningful state revenue-supported increases in the SEEK guaranteed base and Tier I equalization has resulted in local school districts making up for lagging state resources through additional local levies. In addition to shortfalls in state funding for the guaranteed base and Tier I, school districts also must make up for shortfalls in transportation funding. Despite statutory language requiring 100% state funding for estimated district transportation costs, the state has not fully funded the transportation formula since 2004. The most recent budget increased the funding level from roughly 55% to 70% – a modest improvement from prior years but still short of what the statute requires.16

Less state funding, more local reliance leads to greater inequity among districts

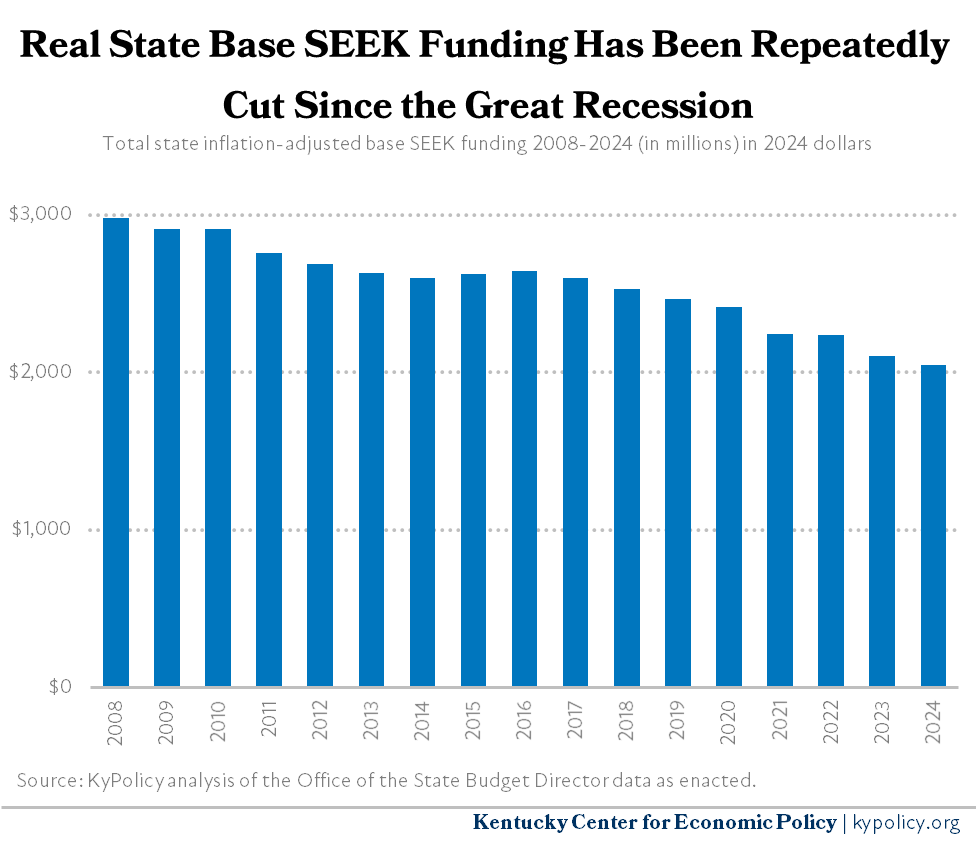

The General Assembly passed tax increases under KERA in 1990 that significantly increased state revenue. But since that time, the General Assembly has chipped away at General Fund resources by increasing tax breaks for businesses and reducing the individual and corporate income tax rates, among other reductions and exemptions. As the economy weakened with the Great Recession, the General Assembly enacted multiple rounds of austere budgets that reduced education funding through direct cuts and freezes, which also amount to cuts once inflation and other cost increases are taken into account.17 The state’s share of base SEEK funding has been cut particularly deeply – when adjusting for inflation, the state portion of the contributions that were meant to ensure an adequately funded system of common schools is now 27% less than it was in 2008.

This steady decline in state support has forced local school districts to turn to their own revenue measures to make up the difference. Those districts with higher property tax bases and more affluent residents have the capacity to partially fill the resulting gap, and those that do not, cannot. This fact is one of the primary reasons that the funding gap between wealthy and poor districts has grown so significantly.

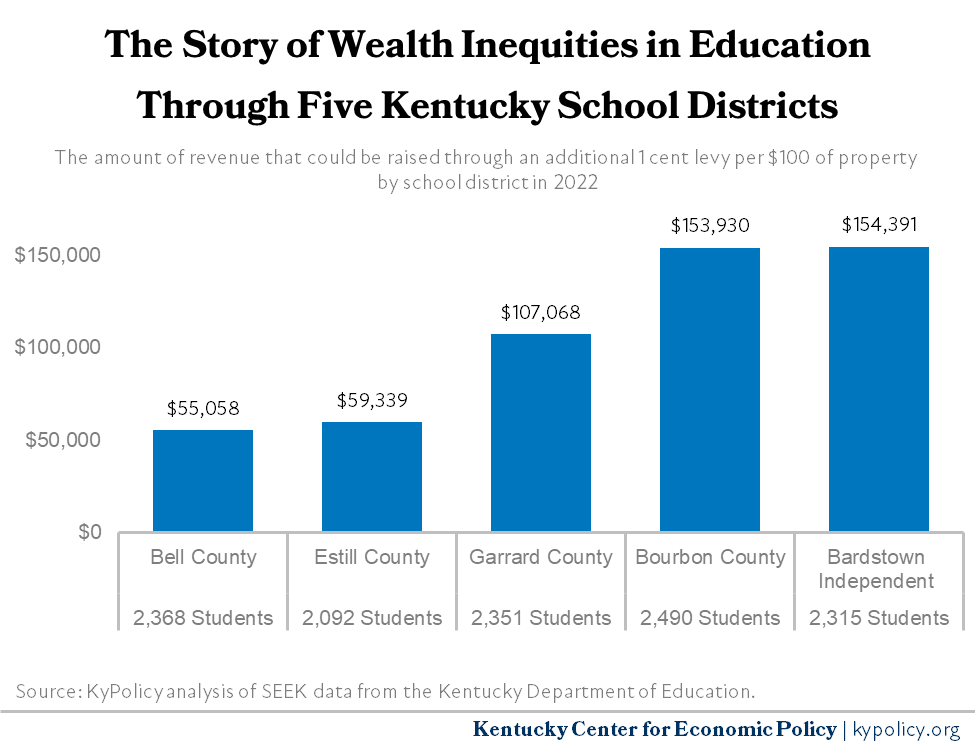

To illustrate this point, in the chart below, consider five school districts with roughly the same number of students, but very different tax bases. Now assume that each district levies a 1 cent tax (meaning an increase in the property tax of 1 cent per 100 dollars in property value). The difference in revenues generated from the same tax effort is stark depending on local wealth. Revenues that could be generated by Bell County are 65% less than those that could be generated by Bardstown Independent. These are not even the most extreme examples, nor is it a recent problem. A KyPolicy analysis showed in 2013 that the same property tax increase would yield over 10 times more revenue for the wealthiest districts than the poorest districts.18

The state’s wealthier districts have also taken advantage of their recent property value growth in an attempt to make up for lagging state investments, while some poorer districts have not had the same opportunity due to their falling property values. The property assessment per pupil went up for the wealthiest quintile by 13% between 2018 and 2022, but only 6% for the poorest quintile. The disparity is even more dramatic for a subset of poorer counties primarily in eastern Kentucky. Letcher, Perry, Martin, Knott and Leslie counties, for example, have seen their property assessments per pupil fall between 7% and 12% since 2018, and between 25% and 43% since 2010.19

The SEEK formula is designed to partially adjust for these changes in local assessments by providing more state money to districts if the assessment base decreases, and less if the assessment base increases. However, because state funding for the SEEK formula has not kept up, a growing portion of the local revenue is not equalized by the formula and therefore districts are not fully compensated when their property assessments decline.

For some districts, the theory is that the reduction in state revenues will be made up through levy of the local rate against the larger tax base. However, the provisions of House Bill 44 passed in 1979 limit the increase in revenues from existing real property to 4% from year to year (with any rate generating more being subject to recall). Districts with existing real property tax bases that grow faster than 4% year over year will generally have to reduce their rate to stay within the 4% limitation. That means the district cannot make up for the loss of state funds using the real property levy as the SEEK formula contemplates, making it more difficult for these districts to protect their funding levels.20

The ability of wealthier districts to levy a wider variety of viable local taxes that are not significant revenue generators in poorer districts is also a factor in the growing disparity. Seven districts that are primarily in metro and suburban areas generate meaningful local revenues from an occupational tax on wages and net profits.21 Those taxes generate significant revenues in counties with plenty of jobs – including jobs that pay higher wages – and lots of business activity, but they would not generate much revenue in poorer counties with scarce employment. Overall, low-wealth districts do not have the same options to address the state-created funding gap that high-wealth districts have. Local tax effort, or the willingness of school boards to raise taxes if needed, is not a meaningful contributor to the growing disparity. For districts as a whole, there is no correlation between property wealth and local tax effort.22

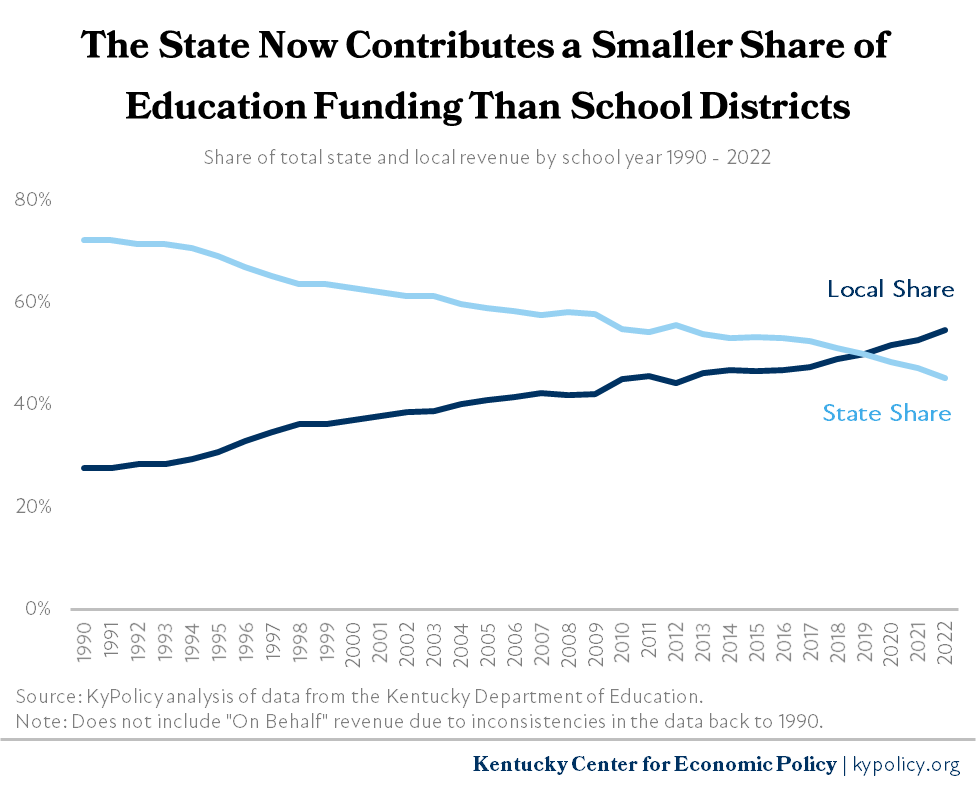

Despite the struggle in many districts to generate revenue, years of underinvestment by the state has resulted in local contributions to per-pupil funding surpassing state contributions for the first time starting in 2020.23

Efforts to reduce or even eliminate the individual income tax and open the door to private school funding further jeopardize public school resources

As previously mentioned, the Rose decision resulted in the General Assembly enacting major tax increases that raised over a billion dollars. These revenue increases were key to ensuring the state had sufficient resources to establish the SEEK formula and ensure important strides toward equitable funding.

But in recent years, Kentucky has chipped away at the individual income tax, the state’s strongest source of revenue that historically funded approximately 40% of the General Fund budget. That began in 2018 with a shift from a progressive income tax structure with a top rate of 6% for high-income Kentuckians to a flat 5% rate for everyone – a change that benefited primarily wealthier Kentuckians.24 Then in 2022, the General Assembly set up a formula to cut the income tax further. Temporary increased revenues due to a strong national economy and high inflation allowed the General Assembly to reduce the income tax rate to 4.5% starting Jan. 1, 2023, and 4% starting Jan. 1, 2024, without making cuts to the budget.

These tax cuts will reduce General Fund revenue by $1.3 billion per year by 2025, making it harder to invest in any of Kentucky’s needs, including SEEK, which is one of the largest appropriations in the state budget.25 The reduction in revenue from income tax cuts is so large that it will be virtually impossible to correct the large inequity in school funding under the current 4% income tax, let alone under future income tax reductions that may occur. When another economic downturn hits, Kentucky’s much lower income tax rate will result in pressure to reduce state funding for public education even further.

In addition, lawmakers are considering a constitutional amendment in 2024 that would allow public tax dollars to go to private schools. This attempt to amend the constitution follows a unanimous state Supreme Court ruling in December that nullified the legislature’s law creating a program of state-funded tax vouchers for private schools. The ruling described how Kentucky’s strong constitutional commitment to public schools disallows public funding of private schools unless approved by a vote of the people.26

Since Kentucky is already having difficulty meeting its constitutional obligations to equitably fund its public schools, as described in this report, amending the constitution to allow the legislature to also fund a separate system of private schools will only make that task more difficult.

We do not have to imagine what it was like in public education prior to the Rose decision, because by the measure highlighted in this report we have arrived at that same level of disparity between school districts in our poorest and wealthiest communities. Kentucky will need a KERA-level commitment to undo the financial harm done to our system of common schools since the mid-1990s. That must start with ending the reductions in our individual income tax, and abandoning new efforts to divert scarce public dollars to a separate system of private schools.

Click here to see fact sheets on the districts with the poorest 20% of property wealth.

- Rose v. Council for Better Education, 790 S. W.2d 186 (Ky. 1989), https://nces.ed.gov/edfin/pdf/lawsuits/Rose_v_CBE_ky.pdf.

- Kentucky Legislature, “Acts of the 2006 Regular Session,” Chapter 170, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/06RS/actsmas.pdf.

- Marcia Ford Seiler, Pam Young, Sabrina Olds et al, “2011 School Finance Report,” Office of Education Accountability, June 12, 2012, https://legislature.ky.gov/LRC/Publications/Research%20Reports/RR389.pdf.

- Sabrina J. Cummins, Allison Stevens, Albert Alexander et al, “Funding Kentucky Public Education: An Analysis Of Education Funding Through The SEEK Formula.” Office of Education Accountability, Oct. 5, 2021, https://legislature.ky.gov/LRC/Publications/Research%20Reports/RR471.pdf.

- Richard E. Day and Jo Ann Ewalt, “Education Reform in Kentucky: Just What the Court Ordered,” Eastern Kentucky University Encompass, 2013, https://encompass.eku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1473&context=fs_research.

- The analysis comparing funding in the first and fifth quintiles for years 1990 through 2010 is from the Office of Education Accountability (OEA). Marcia Seiler et al, “2011 School Finance Report.” KyPolicy’s analysis for 2011-2022 relies on OEA’s methodology. Districts were first sorted by wealth, which is based on districts’ per-pupil property assessments, and quintiles were then determined by the number of students in the annual average daily attendance, achieving as close to 20% as possible without splitting districts. Changes have been made to the underlying data since OEA’s 2012 analysis: in 2014, state on-behalf funds and local activity funds were incorporated into the Kentucky Department of Education’s Audited Financial Reports. On-behalf funds are not included in OEA’s or KyPolicy’s analysis illustrated by the equity chart above. However, isolating activity funds from other local revenue is outside the scope of this report, meaning that these funds are included in KyPolicy’s analysis in years starting in 2014, slightly increasing the equity gap for these years relative to 1990-2013. A couple of factors mitigate the impact this difference makes in comparing the data across all years. First, the impact of activity funds on the equity gap is small: data from the 2012 OEA analysis show that activity funds increased the equity gap by an average of $25 a year (in 1990 dollars) between 2006 and 2010. Second, activity fund reporting is increasing but not yet robust, meaning data starting in 2014 do not reflect the full extent of these resources as a share of revenue in local districts. Activity funds are contributions to schools from individuals and organizations such as Parent Teacher Association (PTA) donations, athletic and other event ticket sales and revenues from fundraising activities.

- Kentucky Department of Education, “Revenues and Expenditures 2021-2022,” accessed Aug. 7, 2023, https://education.ky.gov/districts/FinRept/Pages/Fund%20Balances,%20Revenues%20and%20Expenditures,%20Chart%20of%20Accounts,%20Indirect%20Cost%20Rates%20and%20Key%20Financial%20Indicators.aspx.

- Unlike other state payments, pension contributions that go to paying down unfunded liabilities do not go to schools. They are back payments for contributions the state did not make in the past, as well as actuarial assumptions that were not met, and are a moral and legal debt of the commonwealth. The state has greatly increased pension payments recently after years of not making the full actuarially determined contributions, which had caused the size of these liabilities to balloon. The actual pension benefits themselves have declined in quality for newer cohorts of teachers over time as the legislature has introduced four tiers based on date of hire, each with reduced pension benefits compared to earlier tiers.

- The Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence and the Kentucky Chamber, “A Citizen’s Guide to Kentucky Education: Reform, Progress, Continuing Challenges,” June 2016, http://prichardcommittee.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/A-Citizens-Guide-to-Kentucky-Education.pdf.

- Joseph Stroud, “Governor Signs Historic Education Bill Law Ushers In School Reform, Higher Taxes,” Lexington Herald-Leader, April 12, 1990.

- Kentucky Legislature, “Acts of the 1990 Regular Session”, Chapter 476.

- Districts are also required to levy 5 cents per 100 dollars of assessed property to participate in the state program that supports facility funding, which is separate from SEEK.

- The “adjusted SEEK base” also includes add-ons for transportation, at risk and other student populations with additional needs.

- The tax provisions of KERA operate in conjunction with existing broad-based laws establishing requirements and limitations on the levy of property taxes, commonly referred to as the “HB 44” limitations. HB44, enacted during a special legislative session in 1979, generally provides that any rate levied by a local taxing jurisdiction that generates revenues from real property that are more than 4% above what was generated the prior year is subject to recall by the voters of the district. The interrelationship of the two sets of requirements adds a level of complexity to the local district rate setting process. Marcia Seiler, Pam Young, Albert Alexander and Jo Ann Ewalt, “Understanding How Tax Provisions Interact With the SEEK Formula,” Legislative Research Commission, Nov. 15, 2007, https://legislature.ky.gov/LRC/Publications/Research%20Reports/RR354.pdf.

- Marcia Ford Seiler et al, “Understanding How Tax Provisions Interact With the SEEK Formula.”

- Ashley Spalding, Dustin Pugel and Jason Bailey, “Budget Agreement Includes Only Modest Increase in Most Areas of Budget, Salary Increases for State Workers,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, March 29, 2022, https://kypolicy.org/budget-agreement-includes-only-modest-increases-in-most-areas-of-budget-salary-increases-for-state-workers/.

- Many states are finally investing more in education through their core funding formula since the recession, but Kentucky ranks as the 4th worst among the states for its post-recession per-pupil decline as of 2019. Michael Leachman and Eric Figueroa, “K-12 Funding Up in Most 2018 Teacher Protest States, But Still Well Below a Decade Ago,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 6, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/k-12-school-funding-up-in-most-2018-teacher-protest-states-but-still.

- Jason Bailey, “Vast Inequality in Wealth Means Poor School Districts Are Less Able to Rely on Local Property Taxes,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Dec. 11, 2013, https://kypolicy.org/vast-inequality-wealth-means-poor-school-districts-less-able-rely-local-property-taxes/.

- KyPolicy analysis of property tax data from the Kentucky Department of Education. Numbers are not adjusted for inflation.

- Districts with growing tax bases often have other ways to make up lost revenues that are not subject to the HB 44 limitations. This flaw in the formula has been previously recognized as an issue that should be addressed. See Marcia Ford Seiler et al, “Understanding How Tax Provisions Interact With the SEEK Formula,” and Augenblick, John, and Dale DeCesare. “A Review of the ‘Support Education Excellence in Kentucky’ (SEEK) System.” March 2006.

- Note that occupational taxes levied by school districts can only be imposed against people who both live and work in the school district.

- The top wealth quintile has higher tax rates on average, but the ability to generate significant revenues from occupational taxes is the primary driver. The levied equivalent tax rate – which is a state measure of local school tax effort – is 91.6 cents per 100 dollars of assessed value among the top quintile compared to 72.3 cents among the bottom quintile. The tax effort of poorer districts at the bottom quintile does not, however, differ from the second through fourth quintiles, which have a weighted average rate of 72.5 cents. For 2022, there is a correlation coefficient of 0.03 between assessment value per pupil and levied equivalent tax rate for all districts, which is essentially flat. Excluding Anchorage Independent, an outlier in its per-pupil assessment base, the correlation is -0.04.

- The state vs. local share of per-pupil funding does not include “on-behalf” revenue, a large portion of which is pension contributions that go to pay down unfunded past liabilities.

- Anna Bauman, “New Tax Law Shifts from the Wealthy to Kentuckians of Color and Economically Distressed Regions of the State,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, April 20, 2018, https://kypolicy.org/new-tax-law-shifts-wealthy-kentuckians-color-economically-distressed-regions-state/.

- Jason Bailey, “Top House Priorities Show Conflict Between Reducing Revenues and Rising Costs,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 31, 2023, https://kypolicy.org/ky-cutting-revenues-despite-inflation-raising-costs/. Jason Bailey, “Drop in Income Tax Receipts Is a Glimpse of Future Trouble,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, June 20, 2023, https://kypolicy.org/income-tax-receipts-falling-after-tax-cut/. Jason Bailey, “Reducing the Income Tax Will Weaken the Commonwealth,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 23, 2023, https://kypolicy.org/cutting-kentuckys-income-tax-with-weaken-the-commonwealth/.

- Pam Thomas, “Sending Public Money to Private Schools Breaks Kentucky’s Commitment to Students,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Oct. 25, 2022, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-hb-563-private-school-vouchers/. Council for Better Education v. Johnson, 2022-SC-0518-TG, Dec. 15, 2022, https://appellatepublic.kycourts.net/api/api/v1/publicaccessdocuments/2b85ab46e4368cfdcf2459e6a9086fa726345d2849d8f490dff9771ebff71f4d/download.