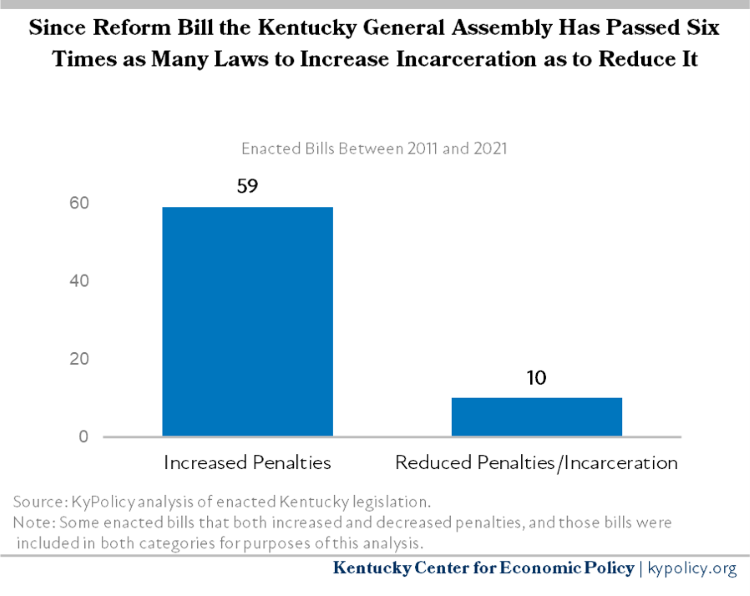

This year marks the 10th anniversary of the passage of 2011’s House Bill (HB) 463, “The Public Safety and Offender Accountability Act.”1 HB 463 was the last significant broad-based reform to Kentucky’s criminal statutes intended to reduce the number of Kentuckians incarcerated, particularly for drug-related offenses, and to free up the increasing public resources being spent on incarceration for more effective investments in safe, healthy communities. Yet year after year since then, the Kentucky General Assembly has passed new laws that lock up more people for longer sentences, far outpacing badly needed efforts to reduce incarceration. Our review of legislation enacted between 2011 and 2021 relating to felony criminal punishment reveals that 59 bills in some way increased or enhanced punishment, while only 10 bills reduced criminalization and incarceration.2

Note: This report is available in PDF format here.

The result of this trend is stark. If Kentucky were a country, it would rank seventh-highest in the world for its rate of incarceration, worse than all countries outside the United States, and all but six other states.3 While a number of other states have made progress in recent years reversing and remedying the punitive criminal penalties enacted during the War on Drugs — resulting in fewer people incarcerated and reduced corrections spending at the same time these states have seen reductions in crime rates — Kentucky continues to increase criminal penalties.4 In particular, harsh penalties for drug-related felony offenses continue to be a driver of Kentucky’s high rates of incarceration, despite clear research that criminal drug laws neither prevent substance use nor address substance use disorder and overdoses.

Criminalization also has a disproportionate impact on communities of color, low-income communities, people with disabilities and other heavily policed groups, entrenching disparities in the criminal legal system and in economic well-being, and creating a barrier to achieving health equity.5 Enhancing criminalization is bad for all Kentuckians, but especially Black Kentuckians, who are disproportionately represented among incarcerated people.6 These disparities aren’t due to differing behaviors between Black and white people, but are instead a legacy of policies and practices within the criminal legal system that make it more likely for Black Americans to be searched, arrested, detained pretrial, charged under habitual offender laws, convicted and sentenced to harsher terms, all of which begin with criminal laws.7 In Kentucky (and 34 other states out of the 44 examined in an Urban Institute analysis), racial disparities in prisons in 2014 were starkest among people serving the longest 10% of terms.8

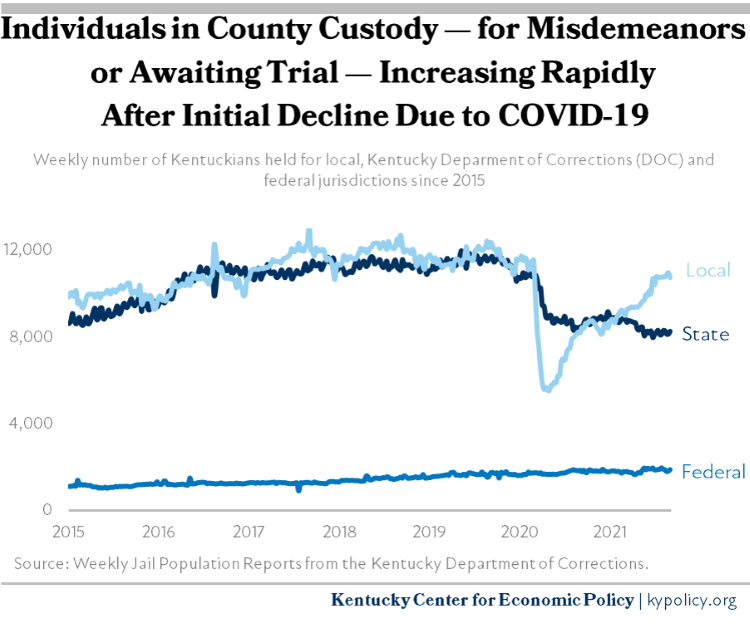

Today, there are over 30,000 people incarcerated in Kentucky’s jails and state prisons and, but for a slight and temporary reduction due to commutations and policy changes related to COVID-19, that number has been growing every year.9 The number of people incarcerated in Kentucky will continue to grow unless there is a significant policy shift away from increased criminalization and punishment, and toward making community investments that provide the support and resources people need to thrive.

This report examines what has happened over the past 10 years in Kentucky leading to more rather than less incarceration. It begins with a look at incarceration trends over the last decade and then explores the General Assembly’s policy choices driving those trends with a primary focus on laws that enhanced criminalization. It concludes with a review of the strong consensus in research that high rates of incarceration do not actually make communities safer, and that alternatives to incarceration are much more effective. Though the vast majority of policies passed in the last decade thwart progress on incarceration, modest but important policy advances in the 2020 and 2021 legislative sessions — through opportunities to earn time off probation and an increase in the felony theft threshold — are steps in the right direction that the legislature should build on going forward.

Reduced incarceration under HB 463 ended up being modest and temporary

The passage of the widely praised HB 463 in 2011 marked a potential new direction for the state’s incarceration trends. Leading up to its enactment, Kentucky had one of the fastest growing prison populations in the nation, increasing by 45% over the decade ending in 2009 compared to a 13% increase for all states.10 Between 1990 and 2010, Kentucky’s state corrections spending grew from $140 million to $440 million — a 214% increase in actual terms. As a result of the criminal justice reforms in HB 463, it was projected that 3,000 fewer people would be incarcerated, the state would save $422 million over 10 years, and a portion of the savings would be reinvested in programs to address substance use, provide mental health treatment and support other efforts to reduce recidivism.11 Provisions in HB 463 intended to reduce incarceration populations and spending included:

- Changing the maximum sentence for Class D felony possession of controlled substances in the first degree from five years to three years.

- Limiting sentence enhancements from Persistent Felony Offender (PFO) statute for possession offenses.

- Incorporating needs and risks assessments during pretrial, sentencing and parole evaluation in an attempt to incarcerate fewer people.

- Allowing for the issuance of citations in lieu of arrests for certain misdemeanor offenses.

- Expanding substance use treatment options for corrections-involved individuals.12

Following the passage of HB 463, there was a modest initial decline in incarceration, but by 2016, the situation in Kentucky was even worse than before — with increases in the number of people serving felony sentences as well as increases in “recidivism,” which is defined as reincarceration within two years.13 Between 2011 and 2016 the number of people incarcerated in Kentucky grew by 8%, resulting in Kentucky having the 10th highest incarceration rate in the country.14

In response, the state requested assistance through the federal Justice Reinvestment Initiative and formed an inter-branch work group in 2017, the Criminal Justice Policy Assessment Council (CJPAC), to “develop fiscally sound, data driven criminal justice policies that protect public safety, hold offenders accountable, reduce corrections populations, and safely reintegrate offenders back into a public role in society.”15 The council noted that the continued alarming growth in incarceration was spurred by many factors including that the number of women incarcerated in Kentucky had grown at a much higher rate than overall population growth, and that too many people were being held pretrial largely due to judges’ decisions to diverge from full adherence to HB 463’s pretrial standards. The primary findings of the work group were that prison admissions — which in Kentucky includes felony sentences being served in county jails as well as state prisons — were being driven by:

- Supervision revocations for technical violations such as missing a meeting or failing a drug test. 61% of prison admissions in 2016 were because of revocations from community supervision — overwhelmingly for technical violations, and over half were related to substance use disorder treatment failures.16

- Increases in Class D felonies (Kentucky’s lowest-level felony), specifically related to drug possession. According to the group’s final report, “Between 2013 and 2016, convictions for drug possession increased by 71 percent, with 47 percent of drug possession convictions being sentenced to prison in 2016. The result was 102 percent growth in the number of drug possession cases sent to prison” between 2012 and 2016.17 Of those sent to prison for simple drug possession in 2016, 42% had no prior felony charges, and 72% had only a single possession charge on that admission, demonstrating that despite discussion of diversion and community services, a very large number of people using drugs were still going to prison.18

The work group issued 22 recommendations, 20 of which were introduced as legislation during the 2018 session of the Kentucky General Assembly as HB 396. The proposal was never voted out of committee.19 Today, 10 years after HB 463 was passed, and nearly 5 years after the CJPAC released its findings, incarceration remains alarmingly high. In 2020, there was an initial reduction after policy changes made in response to COVID-19, but as courts have opened back up, the number of people incarcerated is once again increasing.

While the number of people serving felony sentences in fiscal year 2021 was actually below what it was in 2010, this decline was the temporary result of the governor’s 1,881 sentence commutations in response to COVID-19 combined with court closures during the pandemic that prevented cases from moving forward.20

While harmful for everyone, these trends are worse for heavily policed groups. Specifically, despite being only 8% of the statewide population, Black people make up 21% of Kentucky’s prison population.21 While we do not have state-level data on drug sentencing by race in Kentucky, data from 2014 shows the ratio of arrests for drug possession in Kentucky was close to a 4 to 1 ratio of Black to white arrests.22

The continued high level of incarceration in Kentucky has had a significant financial impact as well. Rather than state appropriations to the Department of Corrections (DOC) declining since 2011, as was the expected result of HB 463, the DOC enacted budget from the General Fund for 2022 is $626 million — a 72% increase from 2010 in actual terms. Over the same period of time, total General Fund expenditures have grown just 45%, reflecting that a growing share of public resources are going to locking people up, instead of being invested in health, child and family services, education and other proven ways to strengthen communities.23

Rising incarceration is not inevitable. It’s a policy choice.

Instead of reducing incarceration and saving critical public resources that could be used to invest in communities, year after year, the Kentucky General Assembly has passed legislation that establishes new crimes and penalties, expands the parameters of existing crimes, enhances already harsh sentencing practices and lengths of incarceration, or otherwise increases punishment. Our review of legislation enacted between 2011 and 2021 relating to felony criminal punishment found that just 10 bills reduced criminalization and incarceration while 59 bills increased or enhanced criminal punishment in some way.24

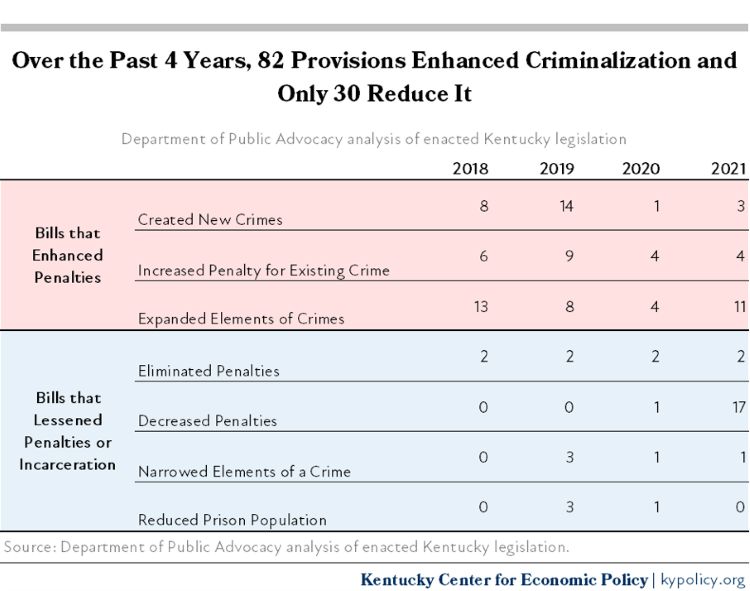

While the above analysis looks at the total number of bills that increase and decrease criminalization, the same trend is apparent when the provisions with bills that include multiple changes are examined. Since 2018, The Department of Public Advocacy (DPA) has identified specific provisions within enacted legislation that either increase or decrease criminalization. As shown below, DPA identified 82 provisions that enhance criminalization and only 30 that reduce it. But even this unfavorable finding may overestimate the positive impact: Of the 17 provisions that decreased penalties in 2021, 14 of those were related to increasing the felony theft threshold from $500 to $1,000 — one change that had to be made in 14 different statutes.

Many of the incarceration-increasing policies passed over the last decade are related to drugs. Historically, harsh penalties enacted as part of the War on Drugs have been a primary driver of incarceration. While research demonstrates the effectiveness and safety of decriminalizing drug use, the General Assembly has doubled down on enhancing punishment, enacting 8 pieces of legislation since 2011 that increase the criminalization of drugs.

For instance, two pieces of legislation — Senate Bill (SB) 192 that passed in 2015 and HB 333 that passed in 2017 —not only fully rolled back HB 463’s reduction in criminal penalties for low-level heroin trafficking, but further enhanced drug-related penalties in a number of ways. One of the harshest changes enacted in these bills was an amendment to the legal definition of trafficking that made sharing or selling any amount of heroin, fentanyl, fentanyl derivatives and carfentanil a minimum Class C felony.25 Cracking down on large-scale drug dealers through enhanced penalties is ineffective policy (discussed in more detail below), but the changes went much further than that: A person who is addicted to heroin and who has no intention of trafficking can be convicted and penalized as such, simply by sharing what they have with someone else. Possession in the 1st degree is a Class D felony, with maximum incarceration time of 3 years, a preference for deferred prosecution (providing time for treatment in the community before charges are actually filed, with dismissal if it is), and presumptive probation rather than incarceration.26 Trafficking, however, is a Class C felony, which carries a 5-10 year sentence, with a requirement that at least 50% of the time be served before a person can be eligible for parole.27

SB 192 included several positive and widely recognized measures related to addressing substance use disorder, including increased funding for treatment services and expanded treatment options, preventing the charging or prosecuting of someone seeking medical assistance for themselves or someone else for drug overdose, expanding availability of naloxone, and authorizing needle exchanges. But in addition to the rollbacks discussed in the previous paragraph, SB 192 also created a new Class C felony for importing heroin, and imposed mandatory minimums and harsher penalties for several existing drug-related crimes. Because criminalization creates barriers to health access for people who use drugs, the positive impacts of SB 192 were undermined by the implementation of harsher criminal penalties.28 In another example from 2012, in an effort to cut down on methamphetamine-related felonies in Kentucky, SB 3 limited the sale of ingredients used in producing methamphetamine. However, it also made possession of the ingredients unlawful (a Class B misdemeanor) for people who have been convicted of methamphetamine-related offenses.29

Other bills enacted by the General Assembly over the last decade that increase criminalization and incarceration, unrelated to drugs, do so in a variety of ways. Since 2011, there were 44 bills that increased penalties for existing crimes or changed elements of existing crimes to make them harsher, 23 bills that created new crimes, and 11 that increased incarceration in some other way.30 Categories of legislation range from serious violent offenses to other behaviors such as abusing corpses, owning “tax zapper” software and using drones in particular ways (there were 3 bills alone in this survey that criminalized drone use in some capacity). While the impact on incarceration from many of these bills was often projected to be minimal, many of these laws ostensibly creating “new” crimes are instead establishing a new and separate crime for behavior that is already criminal. That results in a situation where a person can be charged very harshly with multiple crimes for one act, increasing the likelihood of an enhanced sentence and a longer time incarcerated.

Furthermore, every time the legislature enacts new criminal statutes in an attempt to solve a problem — whether it’s substance use, violence or something else — they lose an opportunity to use time and efforts during the legislative session to pass other bills that would more effectively address the problem through alternative solutions and budgetary investments in strengthening communities. For example, in 2018, the bill comprising positive, harm-reducing suggestions made by the CJPAC (HB 396) — including limited incarceration for probation and parole violations, administrative (automatic) parole for the majority of people serving time for Class C or D offenses, and the lowering of drug possession to a misdemeanor — never passed out of committee.31 In stark contrast, 2017’s “tough on crime” HB 333, which included only provisions enhancing criminalization around drugs, passed the House on a vote of 80-6 and the Senate on a vote of 29-9.

Incarceration fails to make Kentucky communities safer and healthier

There is often a great deal of public and political support for legislation that criminalizes behavior or enhances penalties for an act that is already criminal, especially when the legislation is proposed in response to a particular event that receives significant press coverage. But enhancing criminal penalties does not actually prevent crime or make communities safer — and in fact often works against these goals. Furthermore, Kentucky’s laws are already harsh; an analysis by the Urban Institute shows an upward trend in sentence length in Kentucky between 2007 and 2014, particularly for the longest 10% of sentences.32

Studies have shown that the “tough on crime” policies enacted during the 1990s have largely resulted in incarcerating people with less serious offenses and incarcerating people for longer amounts of time, long after the age in which they are most likely to commit a serious offense (teens to mid-twenties).33 Most people “age out” of criminal behavior. A 2015 research report by the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law finds that after 2000, the effect of incarcerating more people on the crime rate was essentially zero.34 And research consistently shows increased incarceration doesn’t result in lower rates of violent crime.35

According to Daniel Nagin, a leading criminologist and researcher on deterrence, there is less consistent and convincing evidence about the effect of severity of punishment on deterrence, for multiple reasons. One reason is that there are complex motivations and reasoning behind why people commit criminalized acts, such as for economic purposes, social pressures and circumstances (especially among teenagers), or with the belief that they will not be apprehended by authorities.36 Another reason is that many people who commit crimes are not aware of specific punishments or sentences for crimes, and for people who are aware, there may be a diminishing shock value of lengthier sentences becoming even lengthier (i.e., extending a sentence from 20 years to 25 years).37 The supposed “incapacitation” effects of incarceration — removing people who commit crimes from communities — also has little impact on crime particularly once incarceration is so prevalent.38 Even for serious crimes involving interpersonal violence, simply adding more criminal laws does not serve as prevention or otherwise address systemic and root causes of violence.39 Many of the behaviors criminal legislation attempts to address, such as gun violence, domestic and partner violence and child abuse and neglect, are symptomatic of deeper issues including poverty, cyclical trauma, mental health disorders and substance use disorder.40

Similarly, attempting to address drug use and its many harms in Kentucky through criminalization fails as a policy solution. Kentucky has been one of the states hit hardest by the opioid health crisis, and is among the 10 states with the highest overdose death rates (as of this writing, the state was ranked 3rd in the country for the largest increase in overdose deaths over the last 12 months).41 The state continues to see high levels of overdose deaths, including in the years since penalty-enhancing bills were enacted.42 An analysis by Pew examined “whether and to what degree high rates of drug imprisonment affect the nature and extent of the nation’s drug problems.” According to the researchers, if imprisonment was an effective deterrent to drug use and crime, then states with higher rates of imprisonment for drug offenses would have lower rates of drug use among their residents, other things held constant. However, when Pew compared state imprisonment rates for drug offenses with three important measures of state drug problems — self-reported drug use rates (excluding cannabis), drug arrest rates and drug overdose death rates — no statistically significant relationship was found. These results account for variation in states’ education level, unemployment rate, racial diversity and median household income.43

Harsh penalties specifically targeting “dealers” also fail to address harms from drug use. Research shows that incarcerating more people for selling drugs does not reduce the supply of drugs or make communities safer because others step in as long as demand remains high. Harsh penalties aimed at punishing drug “kingpins” to take down organized systems very rarely achieve this goal, instead disproportionately impacting casual drug sellers who aren’t officially affiliated or employed by anyone, and who are mostly users themselves.44 There is a great deal of overlap between people who sell drugs and people who use drugs, so “punishing” the first group even while trying to help the latter — as was the case with SB 192 as described above — ends up being harmful.45

In addition to not effectively deterring or reducing crime and substance use, increased criminal punishment and the resulting longer sentences can actually have the effect of increasing crime. Some research has shown that in states with high rates of incarceration, and also in neighborhoods with concentrated incarceration, increasing the use of incarceration can increase crime. It does so by breaking social ties (i.e., removing people from their families/removing parents from the home), being exposed to criminal habits and networks during incarceration, and because of the collateral consequences of being incarcerated for even a short amount of time, which include employment and housing loss.46

Being incarcerated also correlates with poor health outcomes and reduced life expectancy, regardless of sentence length, and people who are incarcerated experience greater financial instability and hardship, poorer mental health and higher rates of substance use and overdosing.47 Most people enter the criminal justice system in difficult circumstances (economic insecurity, little to no education or certification, and inconsistent work experience) and will most likely leave with similar circumstances. Formerly incarcerated people also face “second-class citizenship” from having a criminal record, which leads to issues obtaining housing, employment, and other social needs.48

As it pertains to drug use and health outcomes in particular, criminalizing drug use creates barriers to health access for people who use drugs by driving drug use underground, increasing the risk of contracting transmissible diseases such as HIV, and discouraging access to emergency services, risk reduction practices and overdose prevention.49 In fact, criminalizing drug use has not reduced drug use broadly or overdose rates, but multiple studies at the national, state and local level have shown that sending people who used drugs to jail/prison leads to higher rates of mortality. In a retrospective longitudinal study conducted over a 30-year time period, a 1 per 1000 within-county increase in jail incarceration rate was associated with 2.6% increase in mortality induced from substance use, and multiple studies have shown that the leading cause of death for people formerly incarcerated during the period immediately after release from prison is drug overdose, with especially elevated risks of death compared with people who have not been incarcerated.50

Investment, not criminalization and incarceration, will move Kentucky forward

Policy solutions exist to help us safely reduce incarceration and its many harms, and to increase safety and well-being in our communities. They are based on real investments in communities to ensure that people have access to the services and supports that they need.

For instance, research shows that providing drug treatment programs in the community that are not a part of the criminal system reduces overall local crime, including offenses that are seemingly unrelated to substance use.51 Providing treatment in the community is also more cost-effective than incarceration. The average cost of an incarceration stint could cover the cost of community psychiatric treatment for someone with mental illness — the latter of which would be more likely to help a person enter recovery.52 Another study in the state of Washington found that spending $1 on drug treatment in prison produced $6 in corrections savings, but that same $1 spending on community-based drug treatment yielded $20 in savings.53

Researchers have also found that expanding Medicaid led to a reduction in violent and property crimes, with one study finding this effect was due to accessing substance use treatment specifically, and another study found the effect more broadly when studying general access to health insurance, meaning even without a focus on substance use treatment, health insurance access reduces crime.54 Finally, while research remains mixed on the best solutions for directly intervening in violence — partially as a result of a lack of long-term investments in programs to address community violence and evaluate what is effective — according to experts, evidence-backed strategies to reduce violence in communities include: improving access to early childhood education, investing in familial supports, enhancing the physical environment (improving quality of buildings, increasing green space, more lighting in public spaces), strengthening peer relationships, engaging youth and supporting skill development, reducing substance use, and mitigating financial stress.55

What is also clear is that investing in community support must happen while reducing criminal laws that bring people in contact with the criminal justice system and lead to incarceration, and Kentucky has taken some steps to achieve this. In the past two years, the General Assembly has passed slightly bolder and more meaningful reforms. In 2020, the passage of HB 284 created probation credits, which can reduce time spent on supervision if an individual participates in certain programs.56 In 2021, HB 126 increased the amount at which theft becomes a felony from $500 to $1,000, putting it more in line with other states; according to the bill’s corrections impact statement, the incarceration-reducing impact will be “significant.”57 Kentucky should build on these steps by rolling back harshly punitive laws like drug criminalization laws — starting with reclassifying drug possession from a felony to a misdemeanor — and other laws like the state’s Persistent Felony Offender law that is one of the broadest and most severe mandatory minimum laws in the country.58 The General Assembly also needs to stop passing more unnecessary criminal laws.

Other states have taken the initiative to roll back harshly punitive criminalization laws that have resulted in lowering incarceration without affecting community safety, such as South Carolina, which eliminated mandatory sentencing for crimes involving drug possession and increased the dollar amount threshold for many felony property crimes, and Mississippi, which scaled back “truth-in-sentencing” policies that required 85% time served for nonviolent offenses and increased the number of people released on parole. Other states such as Rhode Island and Connecticut have eliminated mandatory minimums for all drug crimes.59

- 2011 Ky. Acts, ch. 2, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/11RS/documents/0002.pdf.

- Our analysis of legislation focused on statutory changes related to felonies and does not include misdemeanors, as any misdemeanor sentences are served at the local level.

- Emily Widra and Tiana Herring, “States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2021,” Prison Policy Initiative, September 2021, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/global/2021.html.

- Ashley Spalding, “Kentucky Has Much to Learn from Other States on Criminal Justice Reform,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Jan. 30, 2019, https://kypolicy.org/kentucky-has-much-to-learn-from-other-states-on-criminal-justice-reform/.

- J. Acker, P. Braveman, E. Arkin, L. Leviton, J. Parsons and G. Hobor, “Mass Incarceration Threatens Health Equity in America,” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Dec. 1, 2018, https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2019/01/mass-incarceration-threatens-health-equity-in-america.html.

- Elizabeth Hinton and DeAnza Cook, “The Mass Criminalization of Black Americans: A Historical Overview,” Annual Review of Criminology (January 2021), pp. 261–286.

- Ashley Spalding, “Criminal Justice Reform and Racial Disparities in Kentucky,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Sept. 8, 2016, https://kypolicy.org/criminal-justice-reform-and-racial-disparities-in-kentucky-2/. “Report to the United Nations on Racial Disparities in the U.S. Criminal Justice System,” The Sentencing Project, April 19, 2018, https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/un-report-on-racial-disparities/.

- Leigh Courtney, Sarah Eppler-Epstein, Elizabeth Pelletier, Ryan King, and Serena Lei, “A Matter of Time: The Causes and Consequences of Rising Time Served in America’s Prisons,” Urban Institute, July 2017, https://apps.urban.org/features/long-prison-terms/a_matter_of_time.pdf.

- Department of Corrections, Weekly Jail Population Report, Nov. 12, 2021, https://corrections.ky.gov/About/researchandstats/Documents/Weekly%20Jail/2021/11-12-21%20new.pdf. Department of Corrections, Statewide Population Report, Nov. 22, 2021, https://corrections.ky.gov/About/researchandstats/Documents/Daily%20Population/2021/11/11-22-21.pdf.

- “2011 Kentucky Reforms Cut Recidivism, Costs,” The Pew Center on the States, July 2011, https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2011/2011kentuckyreformscutrecidivismpdf.pdf.

- “2011 Kentucky Reforms Cut Recidivism, Costs,” The Pew Center on the States.

- 2011 Ky. Acts, ch. 2, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/11RS/documents/0002.pdf. “2011 Kentucky Reforms Cut Recidivism, Costs,” The Pew Center on the States.

- Chelsea Thomson and Samantha Harvell, “Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI): Kentucky,” Urban Institute, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2020/03/06/justice_reinvestment_initiative_jri_kentucky.pdf.

- Kentucky CJPAC Justice Reinvestment Work Group, “Final Report,” December 2017.

- The Justice Reinvestment Initiative is a public-private partnership that includes the U.S. Department of Justice, the Bureau of Justice Assistance, and the Pew Charitable Trusts. Kentucky CJPAC Justice Reinvestment Work Group, “Final Report.”

- Kentucky CJPAC Justice Reinvestment Work Group Report.

- Kentucky CJPAC Justice Reinvestment Work Group Report.

- Kentucky CJPAC Justice Reinvestment Work Group Report.

- HB396 18RS, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/record/18rs/hb396.html.

- Robyn Bender, “Commutations,” presentation before Kentucky Budget Review Subcommittee on Justice & Judiciary, Sept. 24, 2021, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/17/13599/Sept%2024%202021%20Bender%20Corrections%20PowerPoint.pdf.

- “Kentucky Population Topped 4.5 Million in 2020,” United States Census Bureau, Aug. 25, 2021, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/state-by-state/kentucky-population-change-between-census-decade.html. “Inmate Profiles,” Kentucky Department of Corrections, Oct. 15, 2021, https://corrections.ky.gov/About/researchandstats/Documents/Monthly%20Report/2020/Inmate%20Profile%20%2010-2021.pdf. “Incarceration Trends in Kentucky,” Vera Institute of Justice, December 2019, https://www.vera.org/downloads/pdfdownloads/state-incarceration-trends-kentucky.pdf.

- “Every 25 Seconds: The Human Toll of Criminalizing Drug Use in the United States,” Human Rights Watch, Oct. 12, 2016, https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/10/12/every-25-seconds/human-toll-criminalizing-drug-use-united-states.

- KyPolicy analysis of Office of the State Budget Director data. Kentucky Office of State Budget Director, 2021-2022 Budget of the Commonwealth, Volume 1, https://osbd.ky.gov/Publications/Documents/Budget%20Documents/2021-2022%20Budget%20of%20the%20Commonwealth/2021-2022%20BOC%20Volume%20I%20-%20FINAL%20-%20%28Part%20B%29.pdf.

- Our analysis of legislation focused on statutory changes related to felonies and does not include misdemeanors, as any misdemeanor sentences are served at the local level. Some enacted bills that both increased and decreased penalties, and those bills were included in both categories for purposes of this analysis.

- 2015 Ky. Acts ch. 66, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/15RS/documents/0066.pdf. 2017 Ky. Acts ch. 168, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/17RS/documents/0168.pdf.

- KRS 218A.1415, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=39533

- KRS 218A.1412, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=49015

- Samuel R. Friedman, Hannah LF Cooper, Barbara Tempalski, Maria Keem, Risa Friedman, Peter L. Flom, and Don C. Des Jarlais. “Relationships of Deterrence and Law Enforcement to Drug-Related Harms among Drug Injectors in US Metropolitan areas.” Aids 20, no. 1 (2006): 93-99. “Every 25 Seconds,” Human Rights Watch.

- 2012 Ky. Acts ch. 122, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/12RS/documents/0122.pdf.

- These totals are based on the categories assigned to legislation by the Department of Corrections in Corrections Impact Statements that accompany the bills through the legislative process. Some bills included provisions that both created new crimes and enhanced existing penalties; these bills were included in both categories.

- Ashley Spalding, “Four Main Ways House Criminal Justice Bill Creates Savings,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Feb. 27, 2018, https://kypolicy.org/four-main-ways-house-criminal-justice-bill-creates-savings/.

- “A Matter of Time: The Causes and Consequences of Rising Time Served in America’s Prisons,” Urban Institute, July 2017, https://apps.urban.org/features/long-prison-terms/data.html.

- Marc Mauer, “Long-Term Sentences: Time to Reconsider the Scale of Punishment,” The Sentencing Project, Nov. 5, 2018, https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/long-term-sentences-time-reconsider-scale-punishment/.

- Oliver Roeder, Lauren-Brooke Eisen, and Julia Bowling, “What Caused the Crime Decline?” The Brennan Center for Justice, 2015, https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/2019-08/Report_What_Caused_The_Crime_Decline.pdf.

- Don Stemen, “The Prison Paradox: More Incarceration Will Not Make Us Safer,” Vera Institute of Justice, July 2017. https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/for-the-record-prison-paradox_02.pdf.

- Daniel S. Nagin, “Deterrence in the Twenty-First Century,” Crime and Justice, (August 2013), pp. 199–263. Marc Mauer, “Long-Term Sentences: Time to Reconsider the Scale of Punishment,” The Sentencing Project, Nov. 5, 2018, https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/long-term-sentences-time-reconsider-scale-punishment/.

- Nagin, “Deterrence in the Twenty-First Century.” Mauer, “Long-Term Sentences.”

- Roeder, ““What Caused the Crime Decline?”

- Alexi Jones, “Reforms Without Results: Why States Should Stop Excluding Violent Offenses From Criminal Justice Reforms,” Prison Policy Initiative, April 2020, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/violence.html.

- Jeff Yungman, “The Criminalization of Poverty,” American Bar Association, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/gpsolo/publications/gp_solo/2019/january-february/criminalization-poverty/. Leigh Goodmark, “Intimate Partner Violence, Criminalization, and Inequality,” UC Press Blog, November 2019, https://www.ucpress.edu/blog/47831/intimate-partner-violence-criminalization-and-inequality/.

- Bruce Schreiner, “Report: Pandemic a role in Kentucky’s Record Overdose Deaths,” AP NEWS, Aug. 04, 2021. https://apnews.com/article/lifestyle-health-pandemics-coronavirus-pandemic-kentucky-9555b1ccdc9df17c9a1e206090fb14b2. Mary Noble and Van Ingram, “2020 Overdose Fatality Report,” Justice & Public Safety Cabinet, Office of Drug Control Policy, https://odcp.ky.gov/Documents/2020%20KY%20ODCP%20Fatality%20Report%20%28final%29.pdf. “Vital Statistics Rapid Release: Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm, accessed on Nov. 30, 2021.

- Noble and Ingram, “2020 Overdose Fatality Report.” “Kentucky Injury and Prevention Center: Drug Overdose Prevention,” https://kiprc.uky.edu/injury-focus-areas/drug-overdose-prevention, accessed on Nov. 30, 2021. “Opioid Overdose Deaths by Race/Ethnicity, 2019” Kaiser Family Foundation, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-deaths-by-raceethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Beth Warren, “Fentanyl killed 763 people in Kentucky – twice as many as heroin,” The Courier-Journal, July 25, 2018, https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/local/2018/07/25/louisville-kentucky-drug-deaths-fatal-overdoses-spike-crystal-meth-fentanyl-heroin-pain-pills-blamed/835740002/.

- “More Imprisonment Does Not Reduce State Drug Problems,” Pew Charitable Trusts, March 8, 2018, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2018/03/more-imprisonment-does-not-reduce-state-drug-problems.

- Joseph E. Kennedy, Isaac Unah, and Kasi Whalers, “Sharks and Minnows in the War on Drugs: A Study of Quantity, Race, and Drug Type in Drug Arrests,” https://lawreview.law.ucdavis.edu/issues/52/2/articles/52-2_Kennedy.pdf. “Pew Analysis Finds No Relationship Between Drug Imprisonment and Drug Problems,” Pew Charitable Trusts, June 19, 2017, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/speeches-and-testimony/2017/06/pew-analysis-finds-no-relationship-between-drug-imprisonment-and-drug-problems.

- “Rethinking the ‘Drug Dealer’,” Drug Policy Alliance, December 2019, https://drugpolicy.org/sites/default/files/dpa-rethinking-the-drug-dealer_0.pdf.

- Stemen, “The Prison Paradox.”

- Sandhya Kajeepeta, Caroline G. Rutherford, Katherine M. Keyes, Abdulrahman M. El-Sayed, and Seth J. Prins, “County Jail Incarceration Rates and County Mortality Rates in the United States, 1987–2016,” American Journal of Public Health (January 2020), pp. S109–S115. Elias Nosrati, Jacob Kang-Brown, Michael Ash, Martin McKee, Michael Marmot, and Lawrence P. King, “Incarceration and Mortality in the United States,” SSM – Population Health (June 2021). Michael Massoglia and William Alex Pridemore, “Incarceration and Health,” Annual Review of Sociology (August 2015), pp. 291–310. Sandhya Kajeepeta, Pia M. Mauro, Katherine M. Keyes, Abdulrahman M. El-Sayed, Caroline G. Rutherford, and Seth J. Prins, “Association Between County Jail Incarceration and Cause-specific County Mortality in the USA, 1987-2017: a retrospective, longitudinal study,” The Lancet Public Health (February 2021). Elias Nosrati, Jacob Kang-Brown, Michael Ash, Martin McKee, Michael Marmot, and Lawrence P. King, “Economic Decline, Incarceration, and Mortality from Drug Use Disorders in the USA Between 1983 and 2014: An Observational analysis,” The Lancet Public Health (July 2019), pp. e326–e333.

- “Every 25 Seconds,” Human Rights Watch.

- Friedman, Samuel R., Hannah LF Cooper, Barbara Tempalski, Maria Keem, Risa Friedman, Peter L. Flom, and Don C. Des Jarlais. “Relationships of Deterrence and Law Enforcement to Drug-Related Harms Among Drug Injectors in US Metropolitan Areas.” Aids 20, no. 1 (2006): 93-99. “Every 25 Seconds,” Human Rights Watch.

- Sandhya Kajeepeta, Pia M. Mauro, Katherine M. Keyes, Abdulrahman M. El-Sayed, Caroline G. Rutherford, and Seth J. Prins, “Association Between County Jail Incarceration and Cause-specific County Mortality in the USA, 1987-2017: A Retrospective, Longitudinal Study,” The Lancet Public Health (February 2021). Massoglia and Pridemore. “Incarceration and Health.” Ingrid A. Binswanger, Patrick J. Blatchford, Shane R. Mueller, and Marc F. Stern, “Mortality after Prison Release: Opioid Overdose and Other Causes of Death, Risk Factors, and Time Trends from 1999 to 2009.” Annals of Internal Medicine 159, no. 9 (2013): p. 592-600. Sungwoo Lim, Amber Levanon Seligson, Farah M. Parvez, Charles W. Luther, Maushumi P. Mavinkurve, Ingrid A. Binswanger, and Bonnie D. Kerker, “Risks of Drug-related Death, Suicide, and Homicide During the Immediate Post-release Period Among People Released from New York City Jails, 2001–2005,” American Journal of Epidemiology,175, no. 6 (2012), p. 519-526.

- Samuel J. Bondurant, Jasom M. Lindo, Isaac D. Swenson, “Substance Abuse Treatment Centers and Local Crime,” National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2016, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w22610/w22610.pdf.

- Bondurant, “Substance Abuse Treatment Centers and Local Crime.” Joseph Vanable, “The Cost of Criminalizing Serious Mental Illness,” National Alliance on Mental Illness, March 24, 2021, https://www.nami.org/Blogs/NAMI-Blog/March-2021/The-Cost-of-Criminalizing-Serious-Mental-Illness.” Rebecca Vallas, “Disabled Behind Bars: The Mass Incarceration of People with Disabilities in America’s Jails and Prisons,” Center for American Progress, July 2016, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/criminal-justice/reports/2016/07/18/141447/disabled-behind-bars.

- Steve Aos, Marna Miller, and Elizabeth Drake, “Evidence-Based Public Policy Options to Reduce Future Prison Construction, Criminal Justice Costs, and Crime Rates,” Olympia: Washington State Institute for Public Policy, October 2006, https://www.wsipp.wa.gov/ReportFile/952/Wsipp_Evidence-Based-Public-Policy-Options-to-Reduce-Future-Prison-Construction-Criminal-Justice-Costs-and-Crime-Rates_Full-Report.pdf.

- Bondurant, “Substance Abuse Treatment Centers and Local Crime.” Jacob Vogler, “Access to Health Care and Criminal Behavior: Short-run Evidence from the ACA Medicaid Expansions,” SSRN, Nov. 14, 2017, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3042267.

- Kala Kachmar, “Louisville is Spending Millions to Stop Gun Violence Before it Starts. Here’s How it Works,” Louisville Courier Journal. Nov. 17, 2021, https://www.courier-journal.com/in-depth/news/investigations/2021/11/17/louisville-now-putting-more-money-toward-different-path-combat-soaring-violence-one-aims-stem-violen/8333320002/. Charles Branas, Shani Buggs, Jeffrey A. Butts, Anna Harvey, Erin M. Kerrison, Tracey Meares, Andrew V. Papachristos, John Pfaff, Alex R. Riquero, Joseph Richardson, Jr. Caterina Gouvis Roman and Daniel Webster, “Reducing Violence Without Police: A Review of Research Evidence,” John Jay College of Criminal Justice, November 9, 2020, https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1370&context=jj_pubs. “Prevention Strategies,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/youthviolence/prevention.html.

- 2020 Ky. Acts ch.284, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/20RS/documents/0044.pdf.

- 2021 Ky. Acts ch. 66, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/21RS/documents/0066.pdf. 2021 HB 126, Corrections Impact Statement, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/recorddocuments/note/21RS/hb126/CI.pdf. Several additional bills have been passed over the past decade that are expected to reduce barriers to successful reentry, and therefore reduce recidivism, over the long term. For example, 2016 HB 40, (https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/16RS/documents/0094.pdf) made some felonies eligible for expungement after a waiting period and for a fee, and 2021 HB 497 (https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/acts/21RS/documents/0182.pdf) made individuals with drug-related felony convictions eligible for food assistance. These bills were, however, outside of the scope of our survey.

- Kentucky’s Persistent Felony Offender law allows for enhanced sentences in certain cases where an individual being prosecuted for a new felony has been convicted of a previous felony.

- Spalding, “Kentucky Has Much to Learn from Other States on Criminal Justice Reform.”