The Kentucky Senate is now considering House Bill (HB) 5, legislation containing the most sweeping expansion of the state’s criminal statutes in decades. In addition to increasing incarceration, hardship and the risk of fatal overdose in Kentucky, the bill would be extraordinarily expensive to state and local governments, but HB 5 still lacks an updated and comprehensive Corrections Impact (CI) statement that would detail its projected cost.

In the absence of such a statement, we analyzed data from a CI on an older version of the bill and information acquired through open records requests. It shows that the bill will easily cost more than $1 billion over the next decade in increased incarceration expenses, and that’s only for the provisions of the bill on which we could obtain data. The extreme cost of the bill is primarily due to the numerous provisions requiring more people to serve longer sentences.

HB 5’s proposed changes to Kentucky’s violent offender statute are among its most expensive

Among the most expensive changes proposed in HB 5 are amendments to the statutory definition of “violent offender” — changes that were made in a last-minute floor amendment filed by the bill sponsor the day before it was voted on by the entire House. These amendments have therefore not yet received much public attention.

The violent offender statute is already expansive

Kentucky’s violent offender statute (KRS 439.3401) currently lists 15 crimes or categories of crimes that designate a person as a violent offender for purposes of probation and parole. In most circumstances, a judge can order a person convicted of a crime to serve their time on probation in the community rather than being incarcerated in a facility. If incarceration is ordered, people are generally eligible to be considered for parole after serving 20% of their sentence. But for many offenses listed in the violent offender statute, probation is not an option, and individuals must remain incarcerated for a much longer time before they can be considered for parole. For example, any person convicted of either a Class A felony (the most serious felony category), or certain Class B felonies identified in the statute, is not eligible for probation at all and must serve 85% of their sentence before being eligible for parole.1

Kentucky’s violent offender statute therefore imposes mandatory minimum sentences based on the offense alone, removing the discretion otherwise available to judges and the parole board to consider all facts and circumstances in each individual case. Mandatory minimum sentences also provide more power and control to prosecutors, who make charging decisions and negotiate plea deals. Plea deals happen in over 95% of criminal cases rather than the case going to trial, often to the detriment of those charged with crimes.

HB 5 adds more offenses to violent offender statute and lengthens sentences

In five different ways, HB 5 makes the violent offender statute even harsher by adding more offenses and lengthening the sentences that those convicted under that statute must serve.

First, HB 5 expands the 85% of sentence served requirement to all felonies listed in the statute, including lower-level Class C and D felonies. As mentioned previously, that requirement currently applies only to more serious Class A and B felonies.

Second, HB 5 expands the offenses that categorize a person as a “violent offender” by adding six new crimes:

- Burglary in the first degree if a person other than the offender is present in the building at the time of the offense. There is no requirement that the person be harmed.

- Robbery in the second degree.

- Strangulation in the first degree.

- Carjacking (a new Class B felony created by Section 9 of the bill).

- Promoting contraband, or knowingly bringing contraband into a jail or prison (a class B felony). Section 15 of the bill enhances the penalty

,from a Class D felony to a Class B for contraband that is fentanyl, carfentanil or a fentanyl derivative. - Wanton endangerment in the first degree involving the discharge of a firearm. Section 38 of HB 5 enhances the penalty if a firearm is discharged in the commission of the offense from a Class D felony to a higher-level Class C felony.2

Third, the bill expands a provision that currently requires anyone convicted of a Class B felony that “results in the death or serious physical injury to a victim” to serve 85% of their sentence. Under HB 5, that provision would apply to all listed Class C and D felonies. This change will have a significant fiscal impact because of the new crimes that will be included without specifically naming them. The following Class C and D felony offenses, and possibly others, will be included based on the elements of the crime: KRS 508.025, KRS 508.110, KRS 507.040, KRS 507.050, KRS 507A.040, KRS 507A.050, and KRS 508.182. In addition, because the proposed change does not require that death or serious physical injury be an element of the crime for the provisions to apply, it is possible for people to fall within this broad expansion for any crime that has as a result a serious physical injury, even if the injury was unintentional.3

For example, assume a person suffers a heart attack as a result of witnessing someone attempting to steal garden tools from their backyard shed. In addition to a low-level felony charge of attempted theft, the prosecutor could also charge the offense as a violent offense under this statute, since as a result of the crime, a person suffered a serious physical injury. In this case, the person would be required to serve 85% of their sentence (which was for an offense not listed in the violent offender statute), even though the person attempting to steal the garden tools had no intent to injure the property owner. In a vast majority of cases, there will be no trial, but the prosecutor can use the option of pursuing a violent offense charge, with its 85% sentence served requirement to induce the defendant to agree to a lengthier sentence than they would receive under current law.

Fourth, HB 5 adds the attempt to commit any crime included in the violent offender category as a violent offense. That means an individual does not necessarily have to carry through with the eligible crimes to be subject to the enhanced penalty requiring they serve at least 85% of the sentence.

Fifth, HB 5 contains a so-called three strikes provision as Section 1 of the bill. This change would require people convicted as a violent offender who had previously been convicted two times as a violent offender at any point in their lifetime, to serve a sentence of life without the possibility of probation or parole or be subject to the death penalty if the third offense is a capital offense.4

These changes will not only directly increase time served, but will give prosecutors more bargaining power, as described above, likely resulting in more plea deals that require longer sentences.

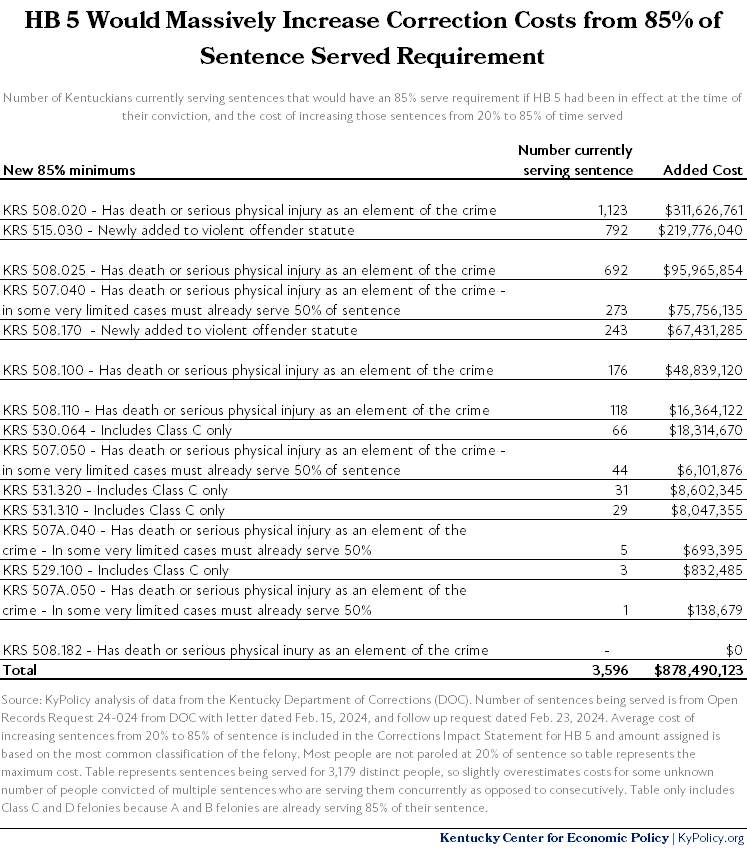

The fiscal impact of proposed changes in the definition of “violent offender” will cost the state over $800 million in the next decade

Using information from the latest CI statement produced by the Kentucky Department of Corrections (DOC) and data from open records requests, we estimated the potential increased correctional costs for the crimes for which data is available that will be subject to the 85% sentenced served requirement included in HB 5. There are several enhancements and added crimes included in HB 5 for which data was not available either because the crimes currently do not exist, or because conditions added for inclusion in the violent offender definition are not separately identified in available data.

This analysis shows that the increased costs to the state for incarceration are over $800 million over the next decade for just the provisions for which data was available. The full cost of the proposed changes to the violent offender statute alone would be even greater if data were available for all additions and enhancements.

The chart above includes people who are currently incarcerated for crimes that would be subject to the 85% sentence served requirement, but the actual cost for these offenses would be significantly greater than reflected in the chart because the proposed changes would also prevent people from being probated for any of the listed crimes (in which they would serve no jail time beyond their initial arrest and pre-trial). There are currently 3,799 people on some form of supervised release for this same group of crimes, many of whom would instead be in jail or prison if the provisions of HB 5 were in effect at the time of their conviction.

HB 5 enhances other penalties that will add hundreds of millions of dollars in costs

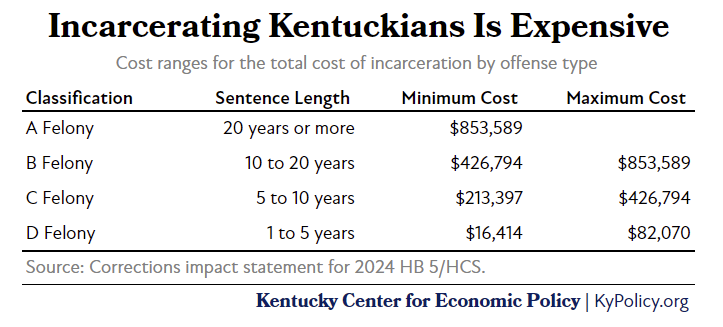

Data is available from the CI to calculate the potential fiscal impact of one other proposed sentence enhancement in the bill. HB 5 increases the penalty for fleeing or evading police in the first degree from a Class D felony to a Class C felony and requires that 50% of the sentence (rather than 20%) be served before the person is eligible for parole (Section 47 of the bill).

There are currently 1,581 people serving time on this charge as a Class D felony. A Class D felony sentence (which state law requires be served in a county jail) costs between $16,404 and $82,070 in total. A Class C felony (which could be served in a county jail or a state prison, with figures here assuming the sentence is served in a state prison) costs between $213,397 to $426,794 in total. If all 1,581 people currently serving time for fleeing or evading in the first degree were instead serving a Class C felony as HB 5 requires, and they served their time in a state prison, the increased cost to the state would range from $311 million to $545 million over a decade just for this one offense.

There are a few more provisions particularly worth mentioning.

Section 2 of HB 5 denies probation and requires that the full sentence be served by any person who possessed a gun during the commission of any offense if the person:

- Was previously convicted of any felony;

- Was on any form of release after conviction of an “offense of violence” (which is not defined); or

- Knew, or was reckless in not knowing that the firearm was stolen.

HB 5 also establishes one new capital offense, one new Class A felony, three Class B felonies, three Class C felonies and one Class D felony. Regarding these new crimes, the CI identifies the following additional costs for each person convicted:

HB 5 will also drastically increase costs to local governments

In addition to increasing costs to the state, HB 5 will worsen crowding in local jails and negatively impact county budgets.

Kentucky’s 72 full service local jails house three broad categories of people:

- People arrested and awaiting trial who have not yet been convicted of a crime (often referred to as “pretrial”), many of whom linger in jail because they cannot afford to post bail to be released. The count

ry is responsible for these costs. - People awaiting transfer to a prison. People in this group have been convicted of a felony and are awaiting transfer to a state prison; this process is referred to as “controlled intake” and it is how the DOC prevents overcrowding in prisons. If state prisons are full, the DOC leaves people in jails until there is room, regardless of whether the jail is overcrowded. The DOC is required to pay a per-diem to the county for this category of incarcerated people in local jails.

- People being incarcerated for other entities, including all people serving Class D felony sentences in state custody, people being held pretrial or serving misdemeanor sentences for convictions in other Kentucky counties that either do not have a jail or are overcrowded, and federal detainees held for ICE or the U.S. Marshal. The county receives a per-diem for this group too, with the amount differing depending on the agreement between the county and the paying entity.

The primary revenue source for local jails incarcerating people for other entities comes from per-diem payments from DOC, which are not sufficient to cover the costs of incarceration, leading in some cases to intentional overcrowding to help make ends meet. According to the most recent jail population report, 47 of Kentucky’s 72 full-service jails are above 100% capacity with six of them, all in rural areas, over 150% of capacity. There is simply no capacity to absorb the significant population increases that local jails will experience if the provisions of HB 5 become law.

HB 5 will increase jail overcrowding and county fiscal costs in the following ways:

- There will be more people held pretrial because the significant number of new crimes and penalty enhancements in HB 5 will likely result in higher bail amounts that people cannot afford to pay. The restrictions on bail funds included in HB 5 will also result in more people who are unable to pay cash bail.

- The number of people convicted of higher-level felonies who are not eligible for probation and who are also subject to the 85% sentence served requirement will increase each year. As prisons fill up, even more people will be in jails waiting for a prison bed to become available, exacerbating an already untenable situation of overcrowding in Kentucky jails.

- With the expansion of the 85% sentence served requirement in the violent offender statute to all Class C and D felonies, people serving their sentences in local jails will be there longer.

- With the increased costs the DOC will experience if HB 5 is enacted, there will be even more incentive for it to keep as many people convicted of felonies as possible in jails rather than prisons, as the average cost differential between incarcerating someone in a jail rather than a prison is $71.96 a day, or $26,265 per year.5

HB 5’s extreme fiscal impact needs to be front and center in policy debates

This analysis calculates that HB 5 will easily add $1 billion in costs over a decade based only on the very limited data that is available. The increase in the incarcerated population will also inevitably result in billions more spent on the construction or expansion of jails and prisons to accommodate the influx of new people into our already overtaxed correctional system. The increase in people incarcerated for a longer portion of their lives will also require new facilities and resources to serve older people with more complex medical needs. DOC estimates that medical incarceration costs $31 more per day than the $117 regular average per day cost of incarceration in a prison, a 26% increase.

- Additional mandatory minimum sentences in the violent offender statutes include requiring people convicted of a capital offense with a life sentence, or a Class A felony with a life sentence to serve at least 20 years; and requiring people convicted of violating KRS 507.040 or 507.050 if the victim was a peace officer, firefighter, or EMS personnel acting in the line of duty, or violating KRS Chapter 507 or 507A in which the victim died as a result of an overdose of a Schedule I controlled substance to serve at least 50% of his or her sentence.

- The bill also specifically lists the crime of Arson in the first degree as an added crime, but it is a Class A felony and as such, is already included in the definition.

- Note that a person can be convicted of some of these crimes without having caused the death or serious physical injury of a victim, and in those cases, they would not be subject to the 85% serve requirement. Note also that in specific and limited circumstances set forth in the statute, some of these crimes already have enhanced sentences of 50% or 85%.

- The most recent corrections impact statement identifies 40 people currently serving sentences who meet the criteria established by this provision. Nine are serving less than 20 years, 26 are serving 20 years or more, and five are serving life sentences. Based on this information, an additional 35 people would be serving life sentences if these provisions were in place at the time of their convictions.

- These figures were calculated using average cost of incarceration in jails and prisons as provided in the latest corrections impact statement on HB 5.