In June 2020, Kentucky had to request a line of credit up to $865 million from the federal government in order to continue paying unemployment insurance (UI) claims during the pandemic, and since then has taken out a $506 million loan. The recent loan is the second time in 15 years that Kentucky has had to borrow because our UI tax structure is inadequate and outdated, leaving our UI trust fund short heading into both the Great Recession and the COVID-19-triggered recession.

As the economy improves following the pandemic, Kentucky will be faced with the gradual task of fully repaying the loan including interest, while simultaneously trying to build up the trust fund balance before the next downturn. HB 413 would delay that process and make eventual increases to achieve trust fund solvency larger, even while giving a poorly targeted tax break that does not provide what businesses most hurting in the pandemic actually need.

Rather than making the financial challenge more difficult, we should be reforming the UI tax system so that it is based on achieving and maintaining trust fund solvency during good times and future borrowing can be limited. In the long run, an inadequate Trust Fund is costlier and doesn’t serve Kentucky’s employers or workers well.

HB 413 freezes statutory tax increases in three ways

In an attempt to prevent a modest increase in UI employer taxes, HB 413 freezes three very small statutory increases that have been either ongoing or were triggered when Kentucky’s trust fund was exhausted.

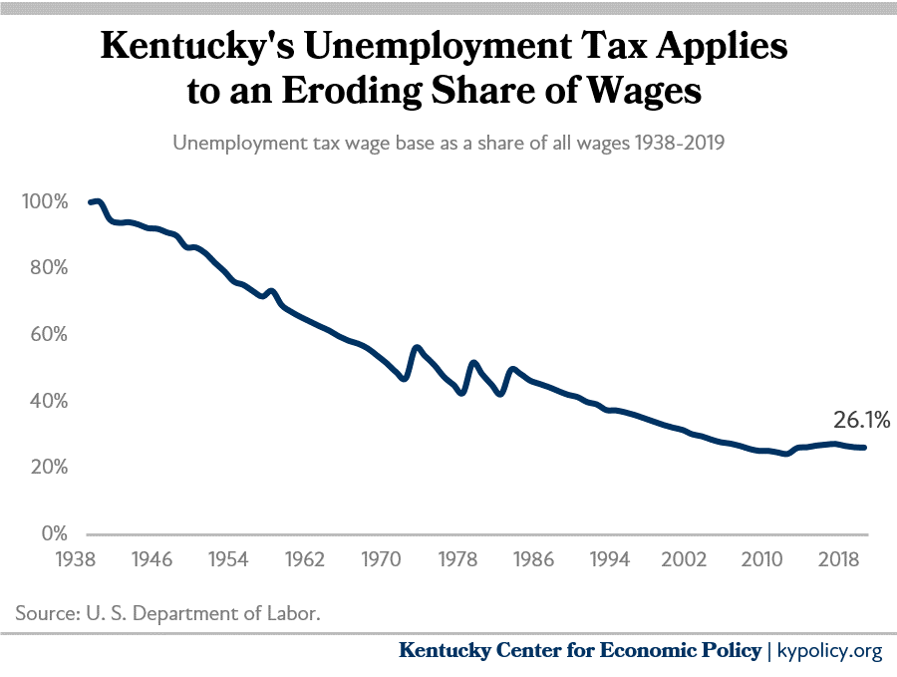

The first is a freeze of the taxable wage base at $10,800 through calendar years 2021 and 2022 (already 44% below the national average taxable wage base), which is otherwise slated to increase to $12,000 in $300 annual increments. This essentially keeps the share of wages that employers pay taxes on very low (which has eroded substantially as shown below), even as wages have risen and will likely continue to rise (albeit slowly) over the next two years. Freezing the rate breaks an agreement between labor and employers in 2010 in which workers received lower benefits moving forward in exchange for slightly higher taxes including an increase in the taxable wage base.

Secondly, the proposal changes the tax schedule for employers from Schedule E — the highest contribution rate that is triggered when the trust fund falls below $150 million — to Schedule A, which is the lowest contribution rate. The current provision with its higher rate is designed to accelerate deposits in the trust fund when the fund is low or negative, ideally avoiding interest payments on the loans, which will be due soon in Kentucky, as well as avoid a higher federal tax as described below.

Finally, the proposed legislation freezes a required surcharge, $21 per employee per year, for calendar years 2021 and 2022. This surcharge was established as part of the solution to shore up the trust fund after the Great Recession, and applies when loans are outstanding and interest payments are owed. Proceeds from this surcharge are used to pay the interest which exceeded $97 million while Kentucky repaid the last loan between 2011 and 2016.

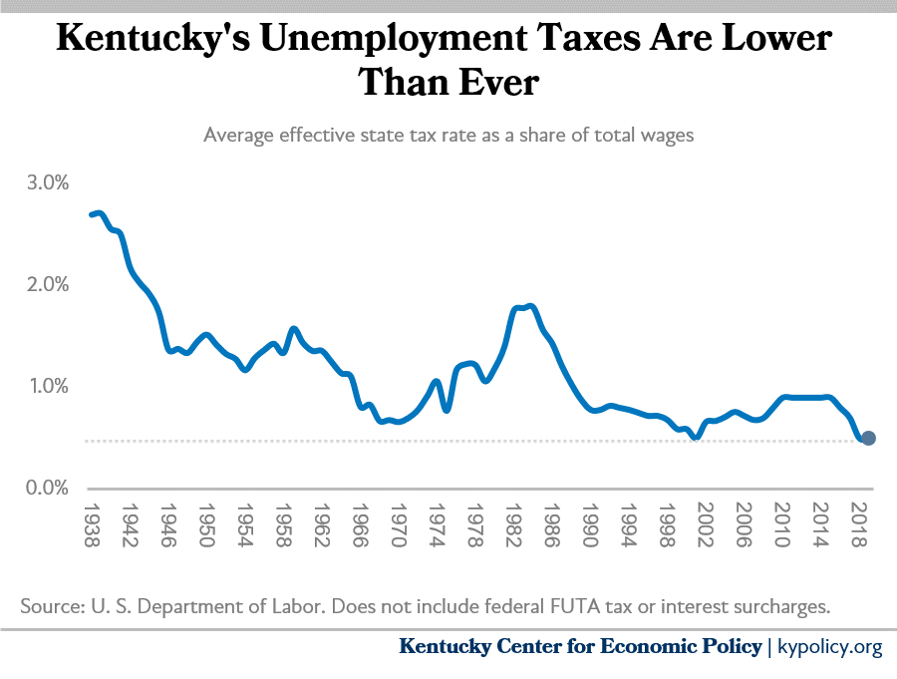

In all, these measures would lock in the lowest employer contribution rate for two more years. That means that even in 2022 when the economy should be in recovery Kentucky’s trust fund would be receiving the smallest share of total wages (under half a percent) of any time in the 83–year history of the program.

Pushing off increased employer contribution delays trust fund solvency and increases federal taxes

Halting the increase in employer contributions through a stalled broadening of the taxable wage base, a frozen rate increase and a moratorium on the surcharge is problematic in two ways. First, reducing payments into the trust fund for two years means that achieving solvency will take longer and Kentucky will be more likely to face the same situation we’ve found ourselves in during the past two recessions: having an inadequate trust fund that forces the state to take out a loan and raise employer contributions while the economy is recovering.

Second, delaying repayment of the loan also means that employers could end up paying more on their Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) obligation. The FUTA obligation is 6% on the first $7,000 in wages, but employers receive a credit of 5.4 percentage points so they only pay 0.6% on that wage base normally. But when a state has an outstanding loan balance for two years in a row, that employer credit gets reduced by 0.6 percentage points initially, and then 0.3 percentage points each year after that, increasing the FUTA rate until the loan is paid off, eventually capping at 6%. So by delaying the contribution increase now, employers may face a state and federal increase in their contribution rates simultaneously in a few years.

Business tax break in HB 413 is too small to constitute meaningful aid and is poorly targeted

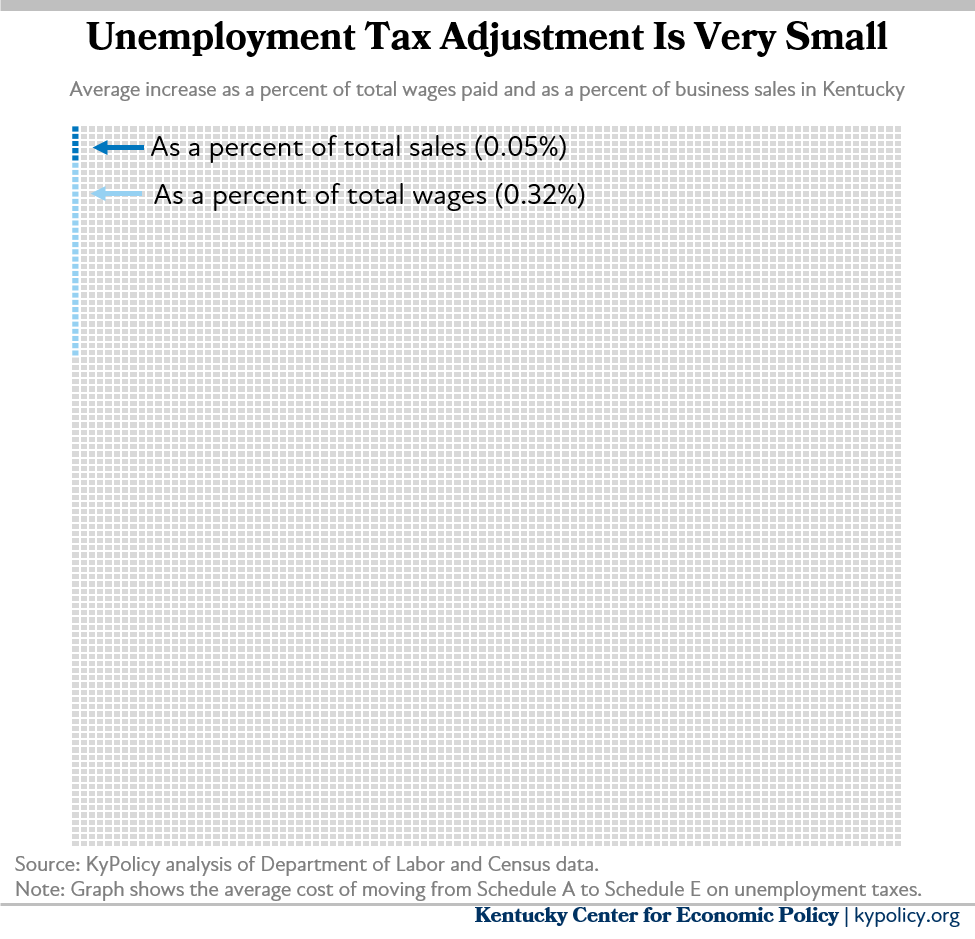

While measures like allowing the employer contribution rate to go from Schedule A to Schedule E, continuing to broaden the taxable wage base and allowing the surcharge to go into effect would help Kentucky pay off our loan more quickly and achieve a positive trust fund balance, they would not have a large impact on employers’ bottom line. For instance, the surcharge is only $21 per employee per year, as previously mentioned, and the increase in the taxable wage base will only result in an extra $5.04 per employee per year on average. Moving employer contributions to Schedule E is the largest of the three increases, but still only increases employer contributions to the trust fund by 0.32% of total wages and approximately 0.05% of business sales on average, as shown in the graph below.

This very small increase in employer contributions would come just as some of the largest employers in Kentucky such as Amazon, Walmart, and Kroger raked in massive increases in net profits last year at 70%, 45% and 90% respectively. It is these large businesses that have the most to gain from freezing the contribution rates, and who need the help the least. Any effort by the General Assembly to provide relief to businesses should be targeted to those that are actually struggling rather than giving the biggest windfall to those that are doing well.

If small businesses that experienced large losses in 2020 need help to stay afloat until the pandemic subsides, then the General Assembly should pursue opportunities for direct aid, such as the proposed $220 million grant fund targeted to struggling small businesses included in HB 191. Like HB 278, which provides a “double dip” tax break for PPP loans to those businesses least likely to need the help, HB 413 is not targeted to those who are hurting the most. It provides the smallest tax break to those businesses that have shed employees or are on the brink of closing and the most help to large, profitable corporations that have grown their workforces in the pandemic.

HB 413 includes a sound measure that holds harmless layoffs related to COVID-19

While employer contribution rates are based on the trust fund balance, they’re also based on each employer’s history of layoffs, known as “experience rating.” Given that many of the layoffs over the past year have largely resulted from the pandemic, and less from decisions made by individual businesses, HB 413 requires that benefits paid to workers for reasons relating to a state of emergency or disaster declaration be taken from the “pooled account.” In doing so, contribution rates of individual employers will not be impacted. That measure in HB 413 is sound and prevents those hurt most from seeing disproportionately higher rates. The bill also sensibly requires that those benefits be accounted for separately in case the federal government offers forgiveness for those benefits as part of a COVID relief package.

Kentucky needs a more sustainable unemployment financing system to protect businesses, workers and the state

Kentucky’s UI trust fund has not been considered solvent by the U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL) since 1974. Solvency, according to the USDOL, means having enough in the trust fund to continue paying out benefits during a recession without borrowing, based on the system’s history of benefit payments (called the high-cost multiple). Kentucky had a high-cost multiple of 0.57 in 2020, which is well below the target of 1, making Kentucky’s UI trust fund the 11th worst-funded in the country. Because of this, Kentucky is now one of 19 states with outstanding federal loans.

Kentucky should establish a system for employer contribution rates tied to and adjusted based on trust fund solvency. If we had done so following the Great Recession, instead of perpetuating the system based on fixed trust fund balances and rates that fall too far when the economy is strong (as Kentucky’s statute does), the state may have avoided taking out another loan or owing interest payments. Moving forward, restructuring our employer contribution system so that it based on trust fund solvency, as proposed in HB 406, will help even out employer contributions over time, and protect workers and employers by making this critical system more financially sound.