The Kentucky Justice Reinvestment Work Group, which held its third meeting this week, plans to propose criminal justice reforms in December for consideration during the 2018 General Assembly. The first step in this process involves exploring in-depth the drivers of our state’s high inmate population, with technical assistance from the Crime and Justice Institute (CJI) at Community Resources for Justice — an organization that has had success helping Louisiana and Alaska identify meaningful and cost saving reforms.

Our state’s criminal justice system is certainly in need of reform. As noted by CJI, Kentucky’s prison population grew 540 percent since the late 1970s and 45 percent just since 2000. We now have the 10th highest imprisonment rate in the nation, 22 percent higher than the national average. We also have the fifth highest female imprisonment rate – almost twice as high as the national average. As of April 2017, 5 jails are over 200 percent of their rated capacity and 30 are over 140 percent. And Department of Corrections (DOC) spending grew $65 million in just 4 years between 2014 and 2017.

Key Drivers of Kentucky’s High Inmate Population

So what is driving our state’s inmate population growth? Here are some findings presented by CJI:

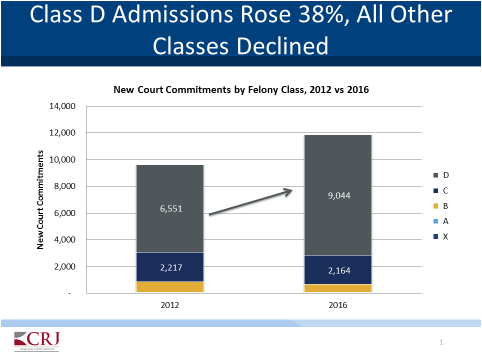

Increase in low-level felony offenses. Growth in low-level “non-person” felony offenses (where a person is not the victim) is a primary driver of the state’s inmate population. The graph below shows that while more serious Class C, B and A felonies did not increase during that time period, Class D felonies grew by 38 percent.

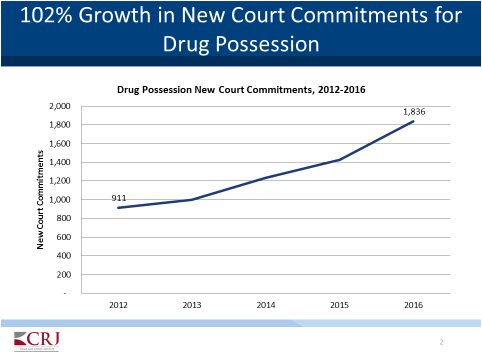

According to CJI, DOC admissions for low-level Class D felony drug possession charges alone increased 102 percent in just 5 years between 2012 and 2016.

However, it should be noted that the state expects to see an uptick in higher level felony convictions with the implementation of HB 333 passed early this year, which increases the charge for low-level heroin and fentanyl trafficking under 2 grams from a Class D felony (the lowest level felony, which carries with it a 1 to 5 year sentence) to a Class C felony (with a 5 to 10 year sentence) and moves parole eligibility from 20 percent of the sentence served to 50 percent.

Many of those incarcerated for low-level offenses are women, with female admissions growing 54 percent between 2012 and 2016 — mostly due to drug offenses or parole violations (discussed below). It is a concern that 70 percent of the total female DOC population is housed in local jails where substance abuse treatment is often not available.

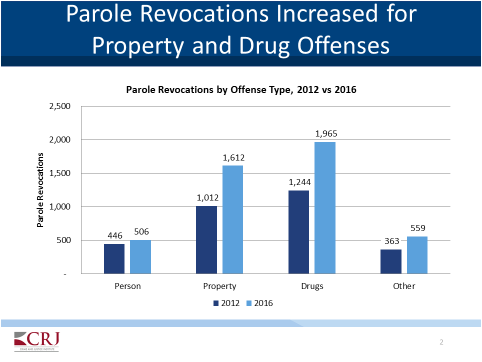

Revocation of supervision. Another driver is supervision (i.e., probation and parole) being revoked for various reasons. In 2016, 61 percent of people entering jail/prison were previously on supervision. DOC admissions for parole revocations have increased 50 percent in 5 years, with increases occurring for property and drug offenses in particular. Sixty percent of the time when supervision (i.e., parole) is revoked after being released from prison it is for technical violations such as failed drug treatment.

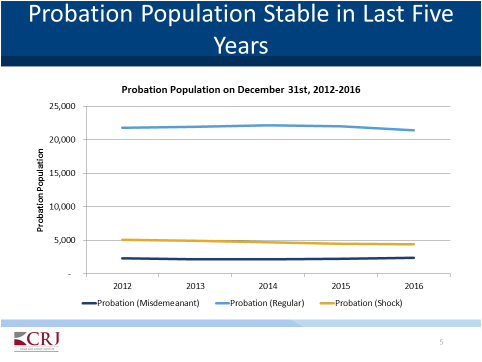

Underutilization of alternatives to incarceration. A majority of felony convictions in Kentucky result in a prison sentence — rather than an alternative such as probation — regardless of felony class. For instance, the rate of probation granted for individuals convicted of simple drug possession (48 percent) is not much lower than for those convicted of more serious drug trafficking (61 percent for Class D trafficking and 66 percent for Class C). The graph below shows that probation rates did not go up between 2012 and 2016, at which time low-level Class D felonies went up and other more serious crimes did not.

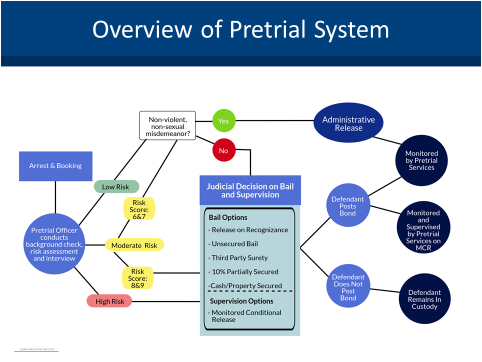

Barriers to pretrial release. Incarcerating individuals pretrial – before they are convicted – also increases Kentucky’s inmate population. Too few individuals with felony charges are released by a judge without bail or through the Administrative Release program, which targets low- and moderate-risk offenders (although its utilization has been growing for those charged with misdemeanors).

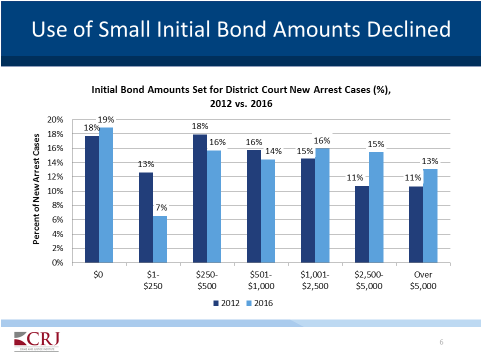

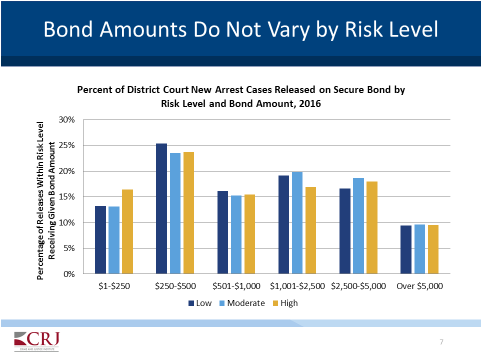

For people awaiting trial who are detained instead of released, bail is supposed to be set based on a risk assessment to determine the potential harm of release pretrial (i.e., risk of violent actions or of fleeing). However, bail/bond amounts often do not reflect a defendant’s level of risk, and for many low-risk offenders it is not affordable. In 2016, 25 percent of District Court cases with final rulings in Kentucky were detained for longer than a week, including 31 percent of low- and moderate- risk cases. Among the factors are substantially more pretrial releases for low-risk defendants requiring a bond secured by a specific asset, and a lower share of initial bond amounts being set at small amounts; not surprisingly, release rates have declined as initial bond amounts increased.

As alluded to, data shows that in practice bond amounts do not vary by risk level, as seen in the graph below.

Even relatively small bond amounts can result in pretrial detainment. There were almost 15,000 cases where defendants were held in jail on bond amounts less than $1,000 in 2016. Meanwhile data shows the frequency of arrest for low- and moderate-risk offenders — including those charged with felonies — is very low. And research shows those detained during the pretrial period tend to have unfavorable outcomes in their court case; for instance, those who were incarcerated the entire pretrial period in Kentucky are more likely to be sentenced to jail/prison and to have longer sentences.

Other Data Trends

A few additional CJI research findings are worth mentioning here:

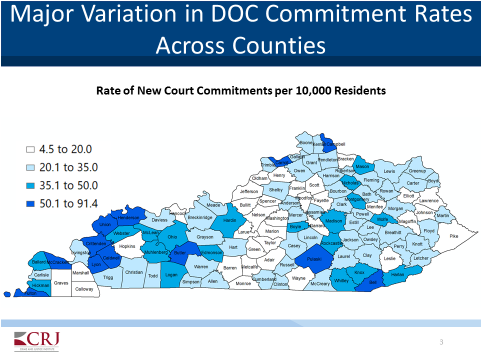

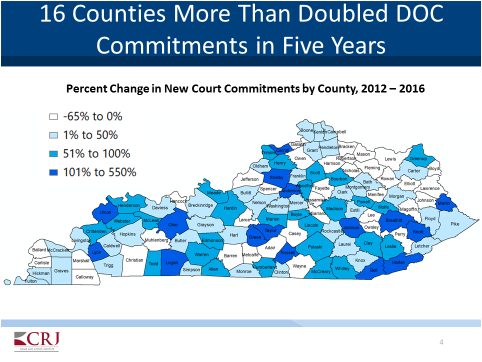

- There is considerable variation in these criminal justice trends by county. For instance, the growth in individuals entering jail/prison varies across the state, with 16 counties more than doubling admissions in 5 years as seen below. Non-metro regions of the state imprison at a higher rate than urban centers such as Louisville and Lexington. Potential causes of this geographic variation were not provided. Despite rhetoric that focuses on troubled communities rather than criminal justice practices, incarceration rates do not correlate with unemployment rates.

- There is also considerable geographic variation in rates of pretrial release, including for low-risk defendants, and in felony indictments — with some circuit courts indicting 10 times more cases per capita than others.

- Almost half of the state’s inmate population (49 percent) is housed in county jails. That is a concerning trend in part because compared to prisons these overcrowded jails lack the facilities needed for inmates serving longer sentences and the programs that help reduce recidivism such as addiction recovery. The DOC jail population grew 31 percent since 2012, driven by the growth in Class D felons. A related issue is major growth in prison bed use for inmates with parole revocations who were originally incarcerated for drug and property crimes — almost 6,000 current prisoners were admitted for technical violations of parole.

- CJI also notes that African Americans are overrepresented in Kentucky’s inmate population. We’ve written elsewhere about these racial disparities in our state’s criminal justice system; for instance, data from Kentucky’s Department of Public Advocacy shows African Americans are more likely than whites to be prosecuted for heroin trafficking rather than the less serious charge of possession.

What These Findings Mean

Rather than being driven by an increase in violent crime across the state (although violent crime in Louisville has increased) or even the long sentences that exist for those with higher level felonies, the data shows Kentucky is spending a significant amount of resources on lower level nonviolent offenses. And incarcerating people for committing these low-level felony crimes may cause more harm than good:

Incarceration can exacerbate recidivism. According to CJI, research shows that in general incarceration is not more effective than alternative sanctions at reducing recidivism — and for many lower-level offenders, incarceration can actually increase recidivism. In 2016, 82 percent of new DOC admissions were sentenced for nonviolent offenses, and more than 75 percent of female inmates in 2016 were sentenced for nonviolent crimes.

Higher rates of incarceration do not drive down crime. The consensus among researchers is that having more inmates behind bars has little if any effect on crime. The impact of incarceration on the national decline in crime that began in the 1990s was found to be marginal, and incarceration in the U.S. is understood to have passed the point of diminishing returns.

Next Steps

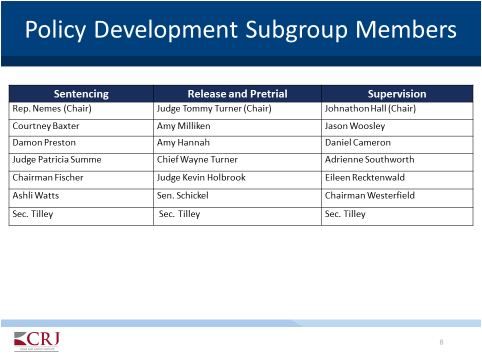

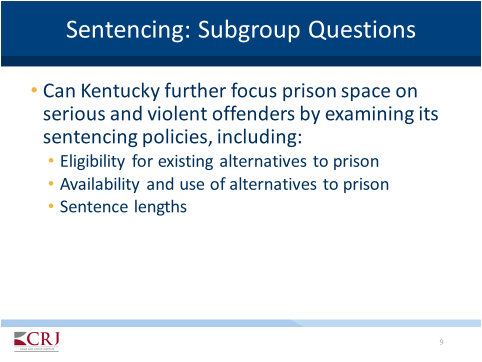

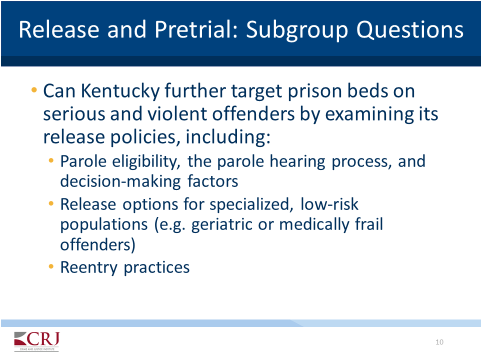

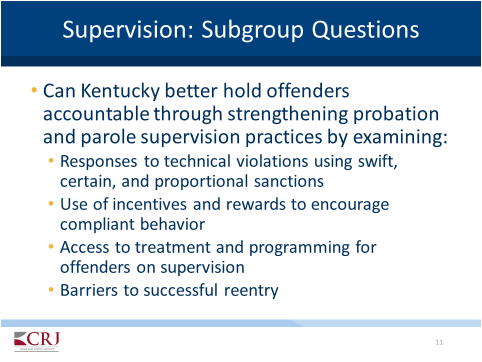

Guided by the data presented by CJI, the Justice Reinvestment Work Group will now split into three subgroups in order to consider questions related to possible reforms around sentencing, release and pretrial policies, and supervision. These work groups begin meeting next week, with subgroups reporting out to the full work group November 29. A report with recommendations will be adopted December 19.

See below for the policy development subgroup members and their guiding questions.