As a result of decreasing reliance on state funding for education and an increasing reliance on local school district resources, the gap in per-pupil funding between the state’s poorest and wealthiest districts is growing. This “equity gap” shrank dramatically in the 1990s after the Kentucky Education Reform Act (KERA) was passed. But since then, the trend has reversed and funding for Kentucky’s school districts has become less equitable, raising the same kinds of issues that prompted the filing of the lawsuit that resulted in the passage of KERA.

In 1989, in Rose v. Council for Better Education, the Kentucky Supreme Court held that the state had failed in its duty, put forth in Section 183 of the Constitution of Kentucky, to “provide for an efficient system of common schools.”1 One of the central tenets of the Rose decision was that the General Assembly must “provide equal educational opportunities to all Kentucky children.” The court explained:

The system of common schools must be adequately funded to achieve its goals…[and] must be substantially uniform throughout the state. Each child, every child, in this Commonwealth must be provided with an equal opportunity to have an adequate education. Equality is the key word here. The children of the poor and the children of the rich, the children who live in the poor districts and the children who live in the rich districts must be given the same opportunity and access to an adequate education. This obligation cannot be shifted to local counties and local school districts.

As a part of KERA, the Office of Education Accountability (OEA) was established and charged with monitoring funding equity among school districts (in addition to other responsibilities). OEA prepared and submitted a School Finance Report each year between 1992 and 2006, with the analysis going back to 1990. In 2006, the General Assembly amended the law to require the report only upon request by the legislative Education Assessment and Accountability Review Subcommittee.2 Since then, OEA has produced just one report with analysis through 2010, which was presented to the subcommittee in 2012.3

This analysis updates that report through 2016, focusing on one specific application of OEA’s quintile-based method – measuring the per-pupil state and local funding gap between the wealthiest districts and the poorest districts that each represent 20 percent of the student population. It provides strong evidence that Kentucky’s education funding continues to grow less equitable.

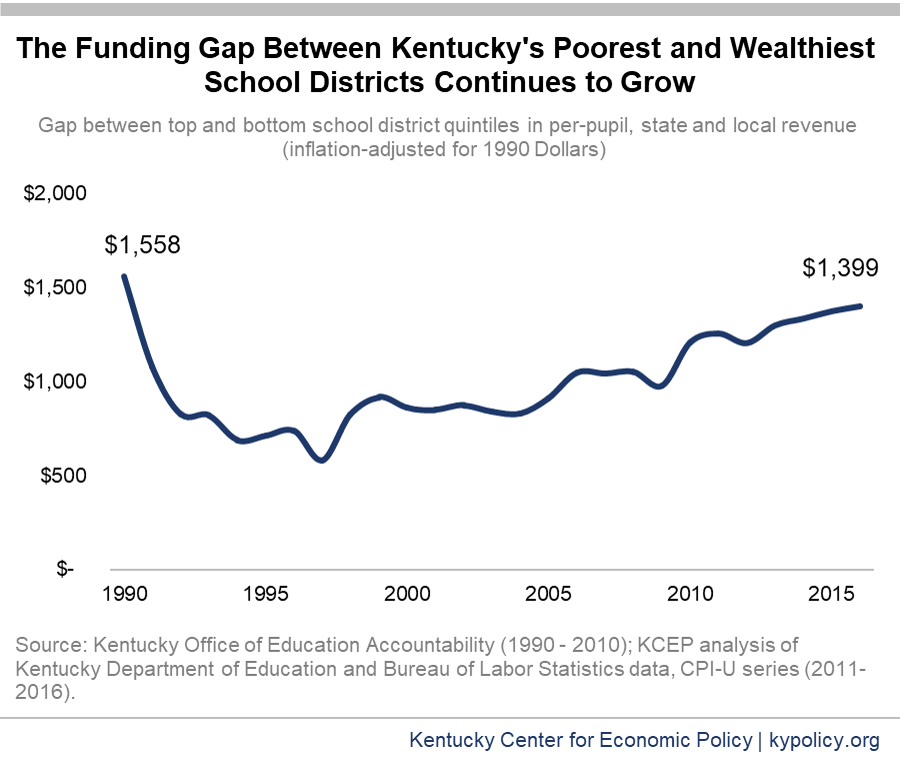

Kentucky’s Education Resource Gap Is Nearing Pre-KERA Levels

OEA has historically used a quintile-based analysis to examine the level of funding equity among school districts. As the graph below illustrates, the gap between the top and bottom quintiles is climbing back toward the level it was before KERA. Adjusted to 1990 dollars, in 2016 state and local funding per-pupil in the poorest Kentucky’s school districts was $1,399 less than in the wealthiest districts, compared to $1,558 in 1990.4 In current dollars, the gap in state and local funding between students in the top and bottom quintiles in 2016 was $2,570.

As a share of total funding for the poorest schools, this gap is not as close to pre-KERA levels as the dollar size shown above, but still headed in that direction. In 1990, the gap in funding between the top and bottom quintiles was equal to 58 percent of state and local funds for the bottom quintile. That share fell to 14 percent by 1997 but has been creeping back up since. In 2016, the gap was almost a third of the bottom quintile’s state and local funds – 31 percent.

OEA’s 2012 analysis looked at the school funding equity gap from a number of angles, including the aggregate equity gap between the wealthiest and each of the other four quintiles, the Gini coefficient and coefficient of variation equity measurements, and with and without on-behalf funding.5 Those different methods all pointed to the same conclusions. In OEA’s words: “while the magnitude of the equity gap varies depending on the method used, all methods consistently show that the equity gap for local and state (combined) revenue has been widening in recent years.”6

Attempting to update each of OEA’s analyses is beyond the scope of this report. However, we did also look separately at the impact of on-behalf funds on school funding equity in 2016. These substantial state resources – $1.3 billion in 2016 – pay for teacher pensions, vocational training and health and life insurance.7 On-behalf funds are not included in the graph above because they have been reported inconsistently over the time period. However, including on-behalf funds using KDE data available more recently and OEA’s 2012 analysis does not mitigate the trend identified in the graph. The total state and local per-pupil funding gap between the 1st and 5th quintiles is widening when on-behalf funds are included — from $2,075 in 2010 according to OEA to $2,625 in 2016 according to KCEP’s analysis (both figures in 2016 dollars).8

Relative to the equity gap that doesn’t include on-behalf funds, OEA found that in 2010 on-behalf funds slightly narrowed the gap in per-pupil funding between the poorest and wealthiest quintiles by $192 (in 2016 dollars). But since then, on-behalf funds have grown more per-pupil in the wealthiest quintile of districts than in the poorest quintile; our analysis shows that on-behalf funds slightly widened the gap in 2016 by $55. Unlike state SEEK funds, state on-behalf funds have little to no equalizing effect on total district resources.9

Mechanisms that Improved Equity Under KERA Rely on Adequate State SEEK Funding

In Rose v. Council for Better Education, the Kentucky Supreme Court was clear that achieving equity would require new revenue – the General Assembly could not just reallocate already inadequate resources. In 1990, legislators responded by passing KERA (HB 940) which – in addition to reforming academic expectations, performance measurement, local decision-making, teacher development, oversight and accountability, wraparound services for students and more – improved funding adequacy and equity.10 The new core funding formula, Support Education Excellence in Kentucky (SEEK), guaranteed a minimum amount of funding per student and established a formula that divides the responsibility between school districts and the state, taking into account district property wealth – or lack thereof.

Through state level tax changes, the legislature raised an estimated $1.3 billion in new revenues for the General Fund over two years, with the vast majority going to education (SEEK and non-SEEK).11 These measures included, in order of their revenue-positive fiscal impact:

- Getting rid of several individual income tax deductions by conforming to the federal tax code, as well as eliminating the state deduction for federal income taxes paid.

- Increasing the sales tax rate from 5 percent to 6 percent.

- Increasing corporate income tax rates by one percentage point, bringing the top rate to 8.25 percent.12

Under the KERA funding formula, local districts are required to levy, through a combination of property, motor vehicle and permissive taxes, a minimum of 30 cents per $100 of assessed property to participate in the SEEK program.13 SEEK funds are distributed on a per-pupil basis, and the amount generated locally is equalized by the state to match the guaranteed SEEK base, which is established by the General Assembly in the biennial budget.14 This formula means local districts with the wealth to generate more revenue receive fewer state dollars, while poorer districts with less capacity to generate revenue receive more from the state.

Local districts also have the authority to:

- Generate an additional 15 percent of the adjusted SEEK base, otherwise known as Tier I funding, which the state partially equalizes. The tax rate that generates Tier I funding, referred to as the “HB 940” rate, is established considering revenues from other permissible taxes levied by the school district. No portion is subject to voter recall. Absent these KERA provisions, school districts would be subject to voter recall on the portion of any levied rate that generates more than 4 percent real property revenue growth over the prior year.15

- Generate up to 145 percent of the adjusted SEEK base, subject to a voter referendum. Amounts generated through this levy are referred to as “Tier II” revenues, and are not equalized by the state. Tier II was established to set an upper limit on local effort, although there are some districts – due to grandfathering and anomalies that occur because of the interaction with other tax provisions – that currently levy a rate exceeding the Tier II upper limit.16

In theory, the shared responsibility between the state and local school districts should provide an adequate baseline of funding for all school districts, while allowing local communities, within limits, to exceed the baseline. In reality, the lack of meaningful state revenue-supported increases in the SEEK guaranteed base and Tier I equalization over the past several years has resulted in local school districts making up for lagging state resources through additional local levies. The state has, for example, shifted from fully funding the costs of transportation in school districts calculated by a formula to funding only slightly more than half of those costs. The increased reliance on local resources for school costs has resulted in a growing funding gap between wealthy and poor districts due to their differing abilities to generate revenue.17

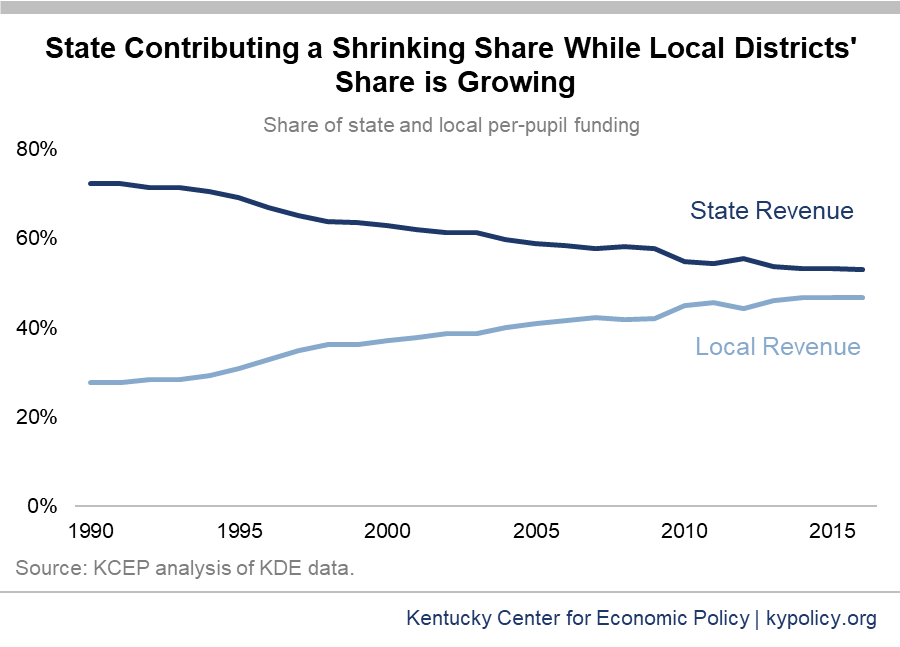

Less State Revenue, More Local Effort

Amendments to the tax code the General Assembly passed under KERA in 1990 increased state revenue, but revenue has eroded since then.18 New and growing tax breaks have left fewer dollars for all public investments including education.19 Since the Great Recession, multiple rounds of state budget cuts have reduced education funding through direct cuts and freezes, which also amount to cuts once inflation and other cost increases are taken into account.20 Including SEEK and non-SEEK funds (which includes revenue for preschool, Family Resource and Youth Centers (FRYSCs), after school programs, textbooks and teacher professional development), audited per-pupil state revenue dropped an inflation-adjusted 14 percent between 2008 and 2016.21

Illustrating the shift in reliance from the state to local governments, total audited per-pupil local revenue increased by 5 percent over the same span of time. This shift has been occurring for decades, as illustrated by the graph below which shows that the share of state and local funding coming from the state has declined, while the share from local districts has increased.22

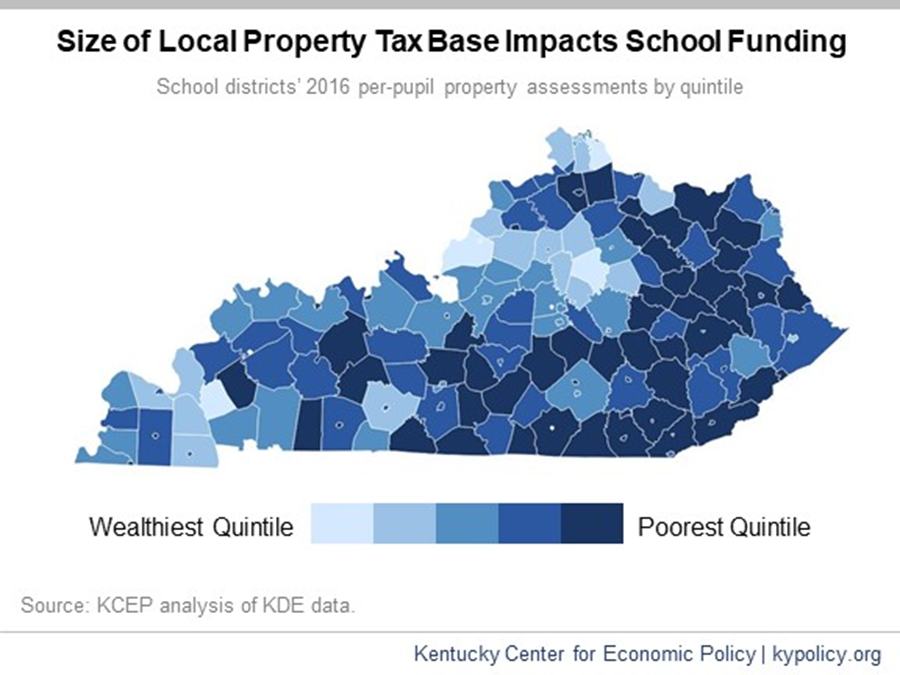

As noted previously, the problem with an increased reliance on local resources – and why such reliance leads to greater disparities in per-pupil funding – is that wealthier school districts have a larger tax base than poorer districts from which to raise additional revenue. In a 2013 analysis of local ability, KCEP estimated that with the same 4 percent increase the richest Kentucky school district could generate over 10 times more revenue per student than the poorest district.23 This 4 percent analysis is particularly relevant because it corresponds with the maximum tax rate a district can typically levy without the voter recall option.24 KDE data show the number of local districts levying the 4 percent rate has increased since KERA and spiked around the recession when state revenue was especially low.25

KDE data also indicate that despite their limited tax bases, poorer districts are demonstrating substantial effort to generate local resources with what they have. In 2016, the median per-pupil property assessment among all 173 school districts was $371,282. For the 82 districts levying the 4 percent rate – with per-pupil assessments ranging from $142,853 to $942,014 – the median property assessment was $373,172. That means a similar number of districts both below and above median property wealth chose to levy the 4 percent rate.

One particular challenge some poor school districts currently face is related to the waning coal industry: as coal companies close or reduce operations in impacted school districts, their tax payments on real and tangible property decrease. In turn, unmined mineral tax revenues decrease as far less coal extraction has led to reductions in the value of coal land that will no longer be mined. Based on analysis of KDE data, in the 2016-2017 school year the re-assessment alone reduced total local funding in the poorest quintile of school districts by $1.2 million and in the second quintile by $2 million. School districts in the top two quintiles were not impacted by the change in unmined mineral assessments.

The map below shows the distribution of quintiles across the commonwealth:

Hard-Earned Gains in Achievement at Risk

Kentucky’s schools have made major strides since KERA. The University of Kentucky’s Center for Business and Economic Research (CBER) found in 2011 that Kentucky had moved up on the Index of Educational Progress between 1990 and 2009 from 48th to 33rd place – more progress than most states (over that time, our neighbor state Tennessee went from 44th to 42nd place).26 CBER also recently found that, once obstacles to cost-effective education spending like poverty, poor health and limited English proficiency are accounted for, Kentucky is one of just 11 states where the return on investment for education spending is higher than would be expected.27 In other words, these dollars are well spent.

Even with Kentucky’s efficiencies, research has found a causal relationship between funding levels and student outcomes. A forthcoming peer-reviewed study in the Quarterly Journal of Economics finds that school finance reforms like KERA improve educational attainment for students from low-income families as well as economic outcomes later in life like wages, family income and poverty incidence.28 Another working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research finds improved equity also helps close achievement gaps between low-income school districts and economically better-off communities.29

The per-pupil state and local funding gap between Kentucky’s wealthiest and poorest school districts is widening and approaching the level it was before KERA. Without significant new state revenue that will grow reliably over time to improve per-pupil funding, we will lose gains made under KERA and experience the consequences of entire communities of students being left behind.

- Rose v. Council for Better Education, 790 S. W.2d 186 (Ky. 1989), https://nces.ed.gov/edfin/pdf/lawsuits/Rose_v_CBE_ky.pdf. ↩

- Kentucky Legislature, “Acts of the 2006 Regular Session,” Chapter 170, http://www.lrc.ky.gov/statrev/tables/06rs/actsmas.pdf. ↩

- Marcia Ford Seiler, Pam Young, Sabrina Olds et al, “2011 School Finance Report,” Office of Education Accountability, June 12, 2012, http://www.lrc.ky.gov/lrcpubs/RR389.pdf. ↩

- In Figure 1, the analysis comparing funding in the first and fifth quintiles for years 1990 through 2010 is from the Office of Education Accountability (OEA). Marcia Seiler et al, “2011 School Finance Report.” KCEP’s analysis for 2011-2016 relies on OEA’s methodology. Wealth is based on districts’ per-pupil property assessments and quintiles are enrollment-based. Changes have been made to the underlying data since OEA’s 2012 analysis: in 2014, state on-behalf funds and local activity funds were incorporated into the Kentucky Department of Education’s Audited Financial Reports. On-behalf funds are not included in OEA’s or KCEP’s analysis illustrated by Figure 1, but are discussed subsequently (for KCEP’s analysis of years 2014-2016, we subtracted on-behalf funds from total state revenue). However, isolating activity funds from other local revenue is outside the scope of this report, meaning that these funds are included in KCEP’s analysis in years 2014-2016, slightly increasing the equity gap for these years relative to 1990-2013. A couple of factors mitigate the impact this difference makes in comparing the data across all years from 1990 to 2016. First, the impact of activity funds on the equity gap is small: data from the 2012 OEA analysis show that activity funds increased the equity gap by an average of $25 a year (in 1990 dollars) between 2006 and 2010. Second, activity fund reporting is increasing but not yet robust, meaning data for 2014 through 2016 do not reflect the full extent of these resources as a share of revenue in local districts. Activity funds are contributions to schools from individuals and organizations such as Parent Teacher Association (PTA) donations, athletic and other event ticket sales and revenues from fundraising activities. ↩

- The report also adjusts the quintile analysis by using a “comparable wage index” to account for district differences in cost of living, and by factoring in federal revenue and local “activity funds.” In 2016, the total local, state and federal funding gap between the first and fifth quintiles was $2,285 (in 2016 dollars, including local activity funds and state on-behalf funds). A full analysis of the equity gap that incorporates federal funding is not included, as we focus on challenges state decision makers have the ability to redress. ↩

- Marcia Ford Seiler et al, “2011 School Finance Report.” ↩

- Kentucky Department of Education, “Revenues and Expenditures 2015-2016,” http://education.ky.gov/districts/FinRept/Pages/Fund%20Balances,%20Revenues%20and%20Expenditures,%20Chart%20of%20Accounts,%20Indirect%20Cost%20Rates%20and%20Key%20Financial%20Indicators.aspx. ↩

- The aforementioned inclusion of activity funds in the underlying KDE data for 2016 increases the equity gap, although the increase is small. As a point of reference, the size of that increase in 2010 was $36 in 2016 dollars. ↩

- Accounting for variations in the cost of living across districts – which are likely reflected in retirement contributions – would refine this analysis of on-behalf funds, but is outside the scope of this report. ↩

- The Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence and the Kentucky Chamber, “A Citizen’s Guide to Kentucky Education: Reform, Progress, Continuing Challenges,” June 2016, http://prichardcommittee.org//www/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/A-Citizens-Guide-to-Kentucky-Education.pdf. ↩

- Joseph Stroud, “Governor Signs Historic Education Bill Law Ushers In School Reform, Higher Taxes,” Lexington Herald-Leader, April 12, 1990. ↩

- Kentucky Legislature, “Acts of the General Assembly; Kentucky Educational Reform Act Revenue Measures,” 1990, Western Kentucky University Library, http://www.wku.edu/library/dlps/documents/keralaw07.pdf. ↩

- Districts are also required to levy 5 cents per $100 of assessed property to participate in the state program that supports facility funding. ↩

- The “adjusted SEEK base” also includes add-ons for transportation, at risk and other student populations with additional needs. ↩

- The tax provisions of KERA operate in conjunction with existing broad-based laws establishing requirements and limitations on the levy of property taxes, commonly referred to as the “HB 44” limitations. HB 44 generally provides that any rate levied by a local taxing jurisdiction that generates revenues from real property that are more than 4 percent above what was generated the prior year is subject to recall by the voters of the district. The interrelationship of the two sets of requirements adds a level of complexity to the local district rate setting process. Martha Seiler, Pam Young, Albert Alexander and Jo Ann Ewalt, “Understanding How Tax Provisions Interact With the SEEK Formula,” Legislative Research Commission, November 15, 2007, http://www.lrc.state.ky.us/lrcpubs/RR354.pdf. ↩

- Marcia Ford Seiler et al, “Understanding How Tax Provisions Interact With the SEEK Formula.” ↩

- Jason Bailey, “Vast Inequality in Wealth Means Poor School Districts Are Less Able to Rely on Local Property Taxes,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, December 11, 2013, https://kypolicy.org/vast-inequality-wealth-means-poor-school-districts-less-able-rely-local-property-taxes/. ↩

- Since 1991, Kentucky’s General Fund has shrunk from 7.33 percent of state personal income to 5.85 percent, which amounts to more than $2.5 billion in less revenue. KCEP analysis of data from the Office of the State Budget Director and Bureau of Economic Analysis. ↩

- Ashley Spalding, et al., “Investing in Kentucky’s Future: A Preview of the 2016-2018 Kentucky State Budget,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, January 4, 2016, https://kypolicy.org/investing-in-kentuckys-future-a-preview-of-the-2016-2018-kentucky-state-budget/. ↩

- Many states are finally investing more in education through their core funding formula since the recession, but Kentucky ranks as the 3rd worst among the states still cutting for its per-pupil decline. Michael Leachman, Kathleen Masterson and Eric Figueroa, “A Punishing Decade for School Funding,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 29, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/a-punishing-decade-for-school-funding. ↩

- KCEP analysis of data from Kentucky Department of Education, “Annual Financial Revenues and Expenditures,” http://education.ky.gov/districts/FinRept/Pages/Fund%20Balances,%20Revenues%20and%20Expenditures,%20Chart%20of%20Accounts,%20Indirect%20Cost%20Rates%20and%20Key%20Financial%20Indicators.aspx. This estimate excludes on-behalf revenue due to the lack of statewide data prior to 2014. ↩

- As explained previously, this analysis (Figure 2) excludes on-behalf funds and includes activity funds in 2014-2016. Including on-behalf funds would increase the share of total state and local funding from the state. Excluding activity funds would slightly reduce the share of total revenue coming from local governments. ↩

- Jason Bailey, “Vast Inequality in Wealth Means Poor School Districts Are Less Able to Rely on Local Property Taxes.” ↩

- In the years after KERA, the HB 940 rate was often higher than the 4 percent rate. But with more districts having achieved Tier I funding, today the 4 percent rate is typically higher. Until legislative action in 2003, school districts were not allowed to adopt the 4 percent rate if it surpassed the Subsection 1 rate associated with HB 44 – the rate that “produces no more revenue than the previous year’s maximum rate.” Especially since then, the 4 percent rate has given districts the most ability to raise revenue. Very few have exceeded the 4 percent limit under HB 44 which makes the decision subject to voter recall. Marcia Seiler et al, “Understanding How Tax Provisions Interact With the SEEK Formula.” See also Kentucky Department of Education, “Local District Tax Levies” and “Historical Tax Rates by Levied Type,” http://education.ky.gov/districts/SEEK/Pages/Taxes.aspx. ↩

- Kentucky Department of Education, “Local District Tax Levies” and “Historical Tax Rates by Levied Type,” http://education.ky.gov/districts/SEEK/Pages/Taxes.aspx. Marcia Seiler et al, “Understanding How Tax Provisions Interact With the SEEK Formula.” ↩

- The index looks at degree attainment rates, ACT scores, high school drop out rates, AP test scores and other national test scores. Michael Childress and Matthew Howell, “Kentucky Ranks 33rd on Education Index,” University of Kentucky Center for Business and Economic Research, July 2011, http://uknowledge.uky.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1006&context=cber_issuebriefs. ↩

- Christopher Bollinger, William Hoyt, David Blackwell and Michael Childress, “Kentucky Annual Economic Report 2017,” University of Kentucky Center for Business and Economic Research, 2017, http://uknowledge.uky.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=cber_kentuckyannualreports. ↩

- Kirabo Jackson, Rucker Johnson and Claudia Persico, “The Effects of School Spending on Educational and Economic Outcomes: Evidence from School Finance Reforms,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, forthcoming, http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~ruckerj/QJE_resubmit_final_version.pdf. ↩

- Julien Lafortune, Jesse Rothstein, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, “School Finance Reform and the Distribution of Student Achievement,” NBER Working Paper, February 2016, http://eml.berkeley.edu/~jrothst/workingpapers/LRS_schoolfinance_120215.pdf. ↩