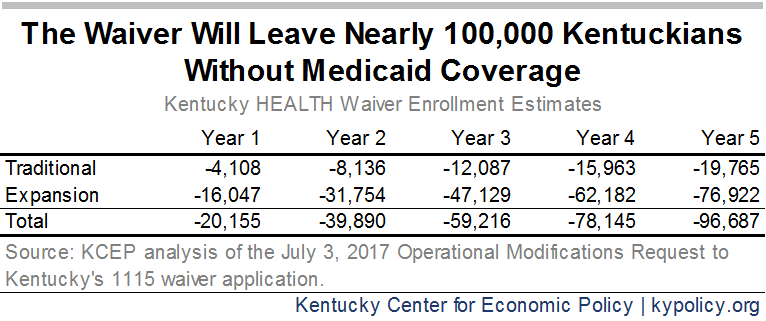

Low-income and disabled Kentuckians are currently eligible for a broad range of health care benefits thanks to Medicaid. As long as people earn below a certain annual wage (a little over $16,700 for adult individuals), or have certain disability-related needs, they qualify. But Kentucky’s recently approved changes to our Medicaid program (known as an 1115 waiver) removes benefits like dental and vision coverage and adds four new ways for people to lose coverage. The documentation attached to the waiver request estimates these new barriers will be the primary reason that 96,687 fewer people will be covered by Medicaid 5 years from now.

1. Work Requirements Are Ineffective and Unprecedented

The waiver includes a mandatory 80 hour per month “community engagement” requirement – which is essentially a work requirement. If non-disabled adults who are covered through the expansion and are not primary caregivers don’t volunteer or work 80 hours per month, they can be locked out of Medicaid for 6 months.

Such a requirement is at odds with the goal of the Medicaid program, which is to provide health coverage for those who cannot afford it. A work requirement will result in fewer people covered by Medicaid and has not been shown to be an effective tool for promoting long-term employment or reducing poverty. Evidence from the work requirements in TANF (cash assistance for low-income families) and SNAP (formerly known as food stamps) show that people don’t end up in well-paying, long term jobs or are being lifted out of poverty because of their participation in a work requirement.

Although Kentucky’s was the first Medicaid work requirement to be approved by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), other states have started to ask for one. For example, a similar request to implement a work requirement in Indiana included an estimate that roughly 30 percent of Medicaid enrollees would be subject to that requirement, and of those, a quarter would lose coverage because they wouldn’t meet the weekly hours required.

2. Premiums Are a Barrier to Coverage for Those Already Struggling to Make Ends Meet

Kentucky’s Medicaid program will also require people who earn above the poverty line ($12,140 for an individual and $25,100 for a family of 4) to pay premiums that increase over time, topping out at $37.50 per month, or else lose coverage. People who earn below the poverty line must also pay premiums that are tied to income levels. If they miss two premium payments they will have to pay co-pays every time they seek care, which can be an impediment to getting needed care and become very expensive for people with health conditions. Only people deemed “medically frail,” children and pregnant women would not be subject to premiums.

Oregon, Utah, Washington and Wisconsin have tried charging premiums for Medicaid enrollees in the past. In each of these states, premiums resulted in enrollment decreases. In Oregon, enrollment dropped by almost half when they began charging premiums for Medicaid.

If Indiana’s mandatory monthly contribution outcomes are indicative, we can expect over half of Medicaid enrollees in Kentucky to miss a payment, with some being locked out of coverage for six months and others being forced to make expensive co-pays every time they go to see a doctor. In Indiana, roughly 60,000 Hoosiers either lost coverage or were never covered because they missed a payment.

3. Reporting Requirement Penalty Is Extreme Given the Nature of Many Low-Wage Jobs

Another way Medicaid enrollees could lose coverage for 6 months is if they fail to report relevant changes in income or work hours. This mandate means if a Medicaid enrollee experiences a change in income or hours that results in Medicaid coverage for which they did not qualify, they will be locked out of coverage for six months.

This provision is especially problematic for Medicaid enrollees due to the kinds of jobs they have. Most Medicaid expansion-eligible adults work, but in jobs with notoriously variable hours and inconsistent incomes like in restaurants, construction and department stores. Workers commonly face “just-in-time scheduling” that can result in people being called into work the day-of or sent home after reporting for a shift. Other examples of low wage work that varies from week to week include tip-dependent server jobs and weather-dependent construction work. Penalizing someone’s failure to report those changes with a six-month disenrollment is both unduly harsh.

4. Annual Re-determination Is Unnecessary and Not Reflective of Other Types of Coverage

With the exception of pregnant women, children and the “medically frail,” enrollees will have to fill out redetermination paperwork each year within a three-month window, starting nine months after their coverage begins and annually thereafter. If an enrollee misses that window they lose coverage and have to wait nine months before they can start receiving benefits again.

Currently, as long as an enrollee’s circumstances have not changed they are re-enrolled automatically, like most anyone who gets insurance through work or who decides to keep a policy they purchased directly from an insurance company. This requirement adds a new, unnecessary hurdle for people to keep Medicaid coverage once they have it.

There are ways Medicaid enrollees can re-enroll prior to the end of their six-month lock out period if they lost coverage due to a work requirement, premium or reporting requirement violation. But by the 5th year of the waiver, nearly 100,000 Kentuckians will still lose coverage, mostly due to these new barriers, according to the most recent waiver application:

It is anticipated that enrollment in Kentucky HEALTH will fluctuate for a variety of reasons, including program noncompliance. Members may have health coverage temporarily suspended for not meeting the community engagement and employment initiative requirements, failing to pay required monthly premiums, or failing to report a change in circumstances.

Medicaid expansion has led to historic gains in coverage and health in Kentucky. With the approval of the Medicaid waiver, the historic progress Kentucky has achieved comes to a halt. These four new barriers to getting covered and keeping coverage will hurt working Kentuckians, health care providers and our economy.