PDF copy – Disparate Justice: Where Kentuckians Live Determines Whether They Stay in Jail

Kentuckians presumed innocent should not have their freedom contingent upon their income or where in the state they are arrested. And yet new data shows widely varying rates between counties in the use of cash bail and in the ability of those arrested to meet those monetary conditions. The share of cases with defendants released pretrial without monetary conditions ranges from just 5% in McCracken County to 68% in Martin County. And just 17% of cases subject to monetary bail in Wolfe County result in the defendant finding a way to make the payment while 99% do in Hopkins County.

The data suggests an arbitrary system of justice based on location. In certain counties, people with low incomes face much higher risk of harms from being detained in jail ranging from job loss to higher likelihoods of being found guilty and committing crimes in the future. In addition, counties that detain more people on monetary conditions face additional jail costs many of them cannot afford.[1]

This data from Kentucky’s Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) underscores the critical need for reform of the pretrial release system in Kentucky, especially as it relates to the imposition of monetary bail as a condition of release. It also raises serious questions about whether there is equal justice statewide due to vastly different pretrial release practices of our local justice systems.

Negative individual, family and community impacts of incarceration widen existing disparities

The consequences of pretrial detention for individuals, families and communities when a person cannot afford bail are devastating and far-reaching – and important context for a conversation about Kentucky’s low and disparate rates of non-financial pretrial release. Because people with low incomes struggle to pay bail – and because historic, structural barriers have resulted in disproportionately low incomes for people of color – these communities in our state bear the brunt of the consequences of our unreformed pretrial system. Several studies have also found that people of color are often treated more harshly than white people during the pretrial release decision-making process.[2]

It can take months for a case to work its way through the system – time during which an individual who is incarcerated pretrial cannot earn income, keep a job or provide caretaking at home, for example.[3] Even those found not guilty of the crime for which they were arrested may lose months of their lives behind bars.

Research also shows people incarcerated pretrial are actually more likely to be found guilty and to receive harsher sentences.[4] Defendants are also more likely to plead guilty (even when they are innocent) when detained pretrial in order to be able to return to their homes and communities.[5] As a result, individuals detained pretrial are more likely to face the collateral consequences of having a felony record – economic insecurity and poor health, not only for themselves, but for their children and other family members as well.[6] Pretrial incarceration is also associated with an increased likelihood of criminal activity in the future.

In addition, it is important to note that most of Kentucky’s local jails are not equipped to provide treatment — pretrial or otherwise — for the many people whose involvement in the justice system stems from a substance use disorder.[7]

The over-incarceration of people pretrial also has a significant impact on costs in our corrections systems, including severe overcrowding in many local jails that is expensive financially, and results in poor living conditions.[8]

Nearly 60% of cases in Kentucky are subject to money bail while defendants await trial

A judge ultimately determines the conditions under which a person who is arrested in Kentucky may be released before trial based on an assessment of risk that they will fail to appear in court and risk that they will engage in new criminal activity if released. (You can read more about the risk assessment in the box at the end of this report.) The options include non-financial and financial terms of release.

Non-financial options for release (or non-financial bond) are:

- Release on recognizance – a person is released without any specific conditions other than appearing at required court dates.

- Unsecured bond – the judge sets a bond amount but the person is not required to pay it to be released; the money would only come due if a person does not come to designated court dates.

- Surety – a third party must sign with the defendant to allow for release; usually the third party is required to own property, although a lien would not necessarily be placed upon the property.[9]

Financial options for release (or financial bond, often referred to as “money bail”) are:

- Cash – a person must pay the full amount set as bail plus fees to be released pretrial.

- 10% bond – a person must pay 10% of the cash amount set as bail before being released.

- Property – a person can be released pretrial if they have an equity interest in property that is equal to twice the amount of bail; a lien is then placed on the property to secure the bail.

By law, money bail in Kentucky cannot be used to punish or detain individuals; it can be used only to ensure reasonable appearance at trial, and only in the amount “sufficient” to do so.[10] However, as described below many defendants in Kentucky are unable to afford bail, which results in them being detained pretrial.

The statistics paint a bleak picture of pretrial release in Kentucky. Just 40% of criminal district court and circuit court cases in Kentucky resulted in release pretrial on non-financial bond.[11] Meanwhile, for those subject to money bail — which is 57% of cases — just 39% (48,866 out of 124,102) resulted in pretrial release.[12] As described later in this report, it is fair to assume that a large share of those subject to money bail who were not released could not afford to pay bail. To provide context, in Washington D.C., more than 90% of defendants are released on non-financial conditions and 5% are released on money bail.[13] Kentucky’s rate of pretrial release with non-financial conditions is also very low compared to a national sample of felony defendants.[14]

At the same time, studies call into question the effectiveness of money bail at ensuring appearance at court and preventing crime. For example, a study by the Pretrial Justice Institute found unsecured bonds are as effective as money bail in protecting public safety and ensuring defendants appear in court.[15] And Kentucky pretrial data shows the appearance rate in court for those released pretrial is already pretty high at 79% overall — 63% for those at highest risk of “failure to appear.”[16] In addition, 89% of individuals released pretrial in 2018 were not charged with new crimes before trial — including 76% of those identified by the assessment instrument as having a higher risk of re-offense. And as a reference point, in Washington D.C., where 9 out of 10 defendants were released with non-financial conditions in 2015, 90% of those released came back to court, and 91% did not re-offend during the pretrial period. In other words, D.C.’s high rate of pretrial release does not correlate with higher rates of flight or pretrial crime relative to Kentucky.[17]

Pretrial release practices vary dramatically by county

Low-income people and Kentuckians of color are disproportionately harmed by a system that relies too heavily on financial conditions of release, but it also depends on where one lives whether or not pretrial release is accessible. There is extreme variation in pretrial practices from county to county under our current system, as demonstrated by AOC data. As shown in the map below, rates of pretrial release on non-financial bonds in 2018 are wildly inconsistent across the state, ranging from just 5% in McCracken County to 68% in Martin County. 65 counties were below the 40% statewide release rate on non-financial bond, which is a low bar.

This wide variation among counties, including neighboring counties, is evidence that the current system is arbitrary. The penalty for being poor for a person arrested in one county could be substantially greater than a person arrested across county lines for the same offense.

Here are a few examples of the dramatic disparities in contiguous counties:

- The rate of pretrial release on non-financial bonds in 2018 in Boyd County was just 17%, while a defendant would have had a better chance of pretrial release in Lawrence County (65%), Carter County (49%) and Greenup County (42%).

- McCracken County, which has the lowest rate of pretrial release on non-financial bond at 5%, borders Marshall County, which has a rate of 51%.

- Henderson County has an 11% rate of release on non-financial bond compared to neighboring Daviess County’s 52%.

- In Shelby County the rate of release on non-financial bond is 19% and Spencer County’s is 24%, compared to Jefferson’s 53% rate of release on non-financial bond.[18]

In other words, where a person is charged with a crime makes a big difference as to whether or not they sit in jail awaiting trial or are released — and whether they face losing employment and other collateral consequences.

Ability to be released if financial conditions are imposed is low and varies significantly by county

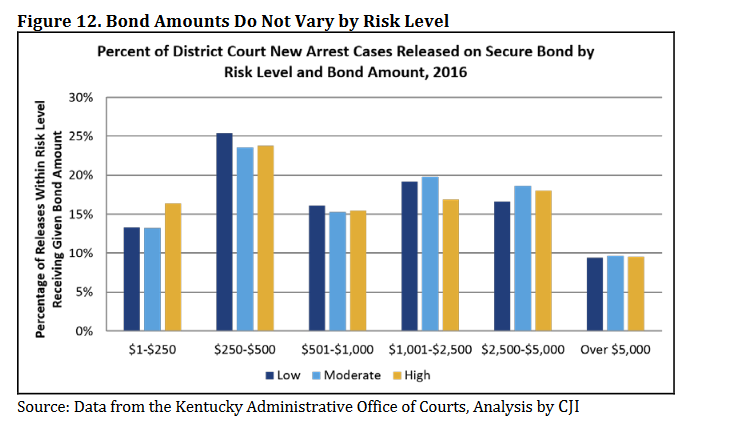

The ability of those offered release with financial conditions to actually meet those conditions also varies significantly among counties and depends on an individual’s economic circumstances and how high judges set financial bail. While the available AOC data doesn’t include the amount of bail or other financial conditions set by judges, it does indicate how many cases subject to financial conditions result in release — which provides an idea of how many cases were set at amounts affordable for defendants. A separate analysis of 2016 AOC data found that for the state as a whole, bond amounts did not correlate with risk levels of defendants (i.e., low risk versus high risk).[19]

As noted previously, for those who are given financial conditions of release, the statewide rate of pretrial release was just 39 percent in 2018. At the county level, in Hopkins County 99% of cases subject to financial conditions resulted in pretrial release, while in Wolfe County, only 17% did. Data is not available to pinpoint why this is the case, but a plausible reason for the disparity is that bail amounts set in Hopkins County may be more affordable than those set in Wolfe County. Regardless, a disparity of this magnitude indicates the need for further study.

The map below shows the variation in pretrial release among counties across the state. It is particularly notable that several counties with very low rates of release on non-financial conditions also have low rates of release on financial conditions: Laurel, Fayette, Todd, Knox, Logan, Breathitt, Powell and Wolfe. This means that if a person is arrested in one of these counties, there is an especially low chance that they will be released pretrial.

Bail reform needed

A mounting

body of research shows that pretrial decisions have a tremendous impact on

individuals, families and communities. And it’s costly to local governments to

detain individuals pretrial, contributing to the state’s jail overcrowding

problems and local budget challenges. Yet the majority of people arrested and

taken to jail in Kentucky pretrial are subject to financial conditions for

release, an insurmountable barrier for many. In addition, dramatically

inconsistent pretrial practices between counties point to the arbitrariness of

our current pretrial practices and the need for legislative pretrial reforms. More

Kentuckians should be released pretrial, and improving statewide standards will

help address these local disparities.

Use of Kentucky’s Pretrial Risk Assessment Tool in Release Decisions

Each defendant receives a pretrial risk assessment that predicts their risk of failing to appear in court and of engaging in new criminal activity if released pretrial.[20] The risk assessment must be considered by the judge, and is performed by Kentucky Pretrial Services, which is a part of the Court of Justice.[21] The risk assessment tool, the Public Safety Assessment (PSA), assigns points based on prior involvement in the criminal justice system, prior failures to appear in court and prior convictions for violent offenses.[22] Based on the assessment, defendants are classified into one of five risk categories ranging from low risk to high risk.

The law requires a judge to release low and moderate risk defendants with non-financial conditions, although the court may require moderate risk defendants to be monitored, drug tested or supervised, and judges may override the findings of the risk assessment instrument if they find a defendant has a high flight or crime risk based on other factors. For those deemed high risk, the law stipulates that judges have discretion in the pretrial decision. Additional evidence beyond the pretrial risk assessment that is allowed into a bail hearing include the nature of the charge itself, marriage or family relationships, years of residency in the county, health, veteran status and danger to the community.[23]

If judges followed directives associated with the state’s risk assessment, and did not override findings, 90% of defendants would be granted immediate non-financial release.[24] In practice, research shows that the risk assessment does not factor heavily into pretrial decisions in Kentucky. Immediately following pretrial reforms enacted in 2011 (House Bill 463) – which resulted in the development of the risk assessment tool currently in use as well as the requirement that judges use it in making release decisions – Kentucky judges changed their pretrial practices and released more low-risk defendants. However, judges soon returned to their previous practices of subjecting more low-risk defendants to unaffordable bail and pretrial incarceration.[25]

Appendix: Pretrial Release Data by County

[1] Kentucky Educational Television, “Bail Reform,” Kentucky Tonight, Feb. 18, 2019. LeónDigard and Elizabeth Swavola, “Justice Denied: The Harmful and Lasting Effects of Pretrial Detention,” Vera Institute of Justice, April 2019, https://www.vera.org/publications/for-the-record-justice-denied-pretrial-detention. Patrick Liu, Ryan Nunn and Jay Shambaugh, “The Economics of Bail and Pretrial Detention,” The Hamilton Project, December 2018, http://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/BailFineReform_EA_121818_6PM.pdf.

[2] Digard and Swavola, “Justice Denied.” A study of pretrial decisions in Miami and Philadelphia found bail judges in these cities are racially biased against Black defendants. David Arnold, Will Dobbie and Crystal Yang, “Racial Bias in Bail Decisions,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics (November 2018), pp. 1885-1932, https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/133/4/1885/5025665?redirectedFrom=fulltext. While Kentucky’s pretrial practices have not specially been studied in this way, we do know that African Americans are significantly overrepresented in the state criminal justice system. Ashley Spalding, “Criminal Justice Reform and Racial Disparities in Kentucky,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Sept. 8, 2016, https://kypolicy.org/criminal-justice-reform-and-racial-disparities-in-kentucky-2/.

[3] Administrative Office of the Courts, “District Court Closing Caseload, Average Months Between Filing Date to Closing Date,” https://courts.ky.gov/aoc/statisticalreports/Documents/INS054.pdf. Administrative Office of the Courts, “Circuit Court Closing Caseload, Average Months Between Filing Date to Closing Date,” https://courts.ky.gov/aoc/statisticalreports/Documents/INS051.pdf.

[4] Digard and Swavola, “Justice Denied.” J. Acker, P. Braveman, E. Arkin, J. Parsons and G. Hobor, “Mass Incarceration Threatens Health Equity in America,” Jan. 15, 2019, https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2019/01/mass-incarceration-threatens-health-equity-in-america.html.

[5] David Arnold, Will Dobbie and Crystal Yang, “Racial Bias in Bail Decisions,” IRS Working Paper, https://www.princeton.edu/~wdobbie/files/racialbias.pdf.

[6] J. Acker, P. Braveman, E. Arkin, L. Leviton, J. Parsons and G. Hobor, “Mass Incarceration Threatens Health Equity in America,” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Jan. 15, 2019, https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2019/01/mass-incarceration-threatens-health-equity-in-america.html.

[7] Legislative Research Commission, “State Inmates Housed in County Jails in Kentucky,” Nov. 24, 2017, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/lrc/publications/ResearchReports/RR430.pdf.

[8] Legislative Research Commission, “State Inmates Housed in County Jails in Kentucky.”

[9] These types of pretrial release are subject to approval on a local basis. If the defendant does not show up for court appearances, or does not abide by conditions imposed by the court, the third party surety may be subject to forfeiture by the court (the amount of the forfeiture would be the amount set as bail). Kentucky Court of Justice, “Interview Process & Release Alternatives,” https://courts.ky.gov/courtprograms/pretrialservices/Pages/interviewrelease.aspx.

[10] B. Scott West, “Five Bail Cases the Kentucky Criminal Defense Attorney Absolutely Must Know (and Why),” The Advocate, January 2017, https://dpa.ky.gov/Public_Defender_Resources/The%20Advocate/Advocate%20Newsletter%20Jan%202017%20(COLOR%20-%20FINAL).pdf.

[11] For most misdemeanor charges, defendants in Kentucky with low and moderate risk scores are now automatically released on recognizance to await trial, without going before a judge. This is a relatively recent development known as “administrative release. The release rates described in this report exclude administrative releases and also cases without a bond hearing. B. Scott West, “The Next Step in Pretrial Release Is Here: The Administrative Release Program,” The Advocate, January 2017, https://dpa.ky.gov/Public_Defender_Resources/The%20Advocate/Advocate%20Newsletter%20Jan%202017%20(COLOR%20-%20FINAL).pdf.

[12] The other 3% of cases were not offered any type of release. These are cases where there is a perceived presence of overwhelming proof of guilt.

[13] Pretrial Justice Institute, “The Pretrial Services Agency for the District of Columbia: Lessons From Five Decades of Innovation and Growth,” Aug. 22, 2018, https://university.pretrial.org/HigherLogic/System/DownloadDocumentFile.ashx?DocumentFileKey=46b516e0-5ea0-a9a3-b070-ecd6bacd9ed0&forceDialog=0.

[14] Megan Stevenson, “Assessing Risk Assessment in Action,” Minnesota Law Review (August 2017), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3016088.

[15] Michael R. Jones, “Unsecured Bonds: The As Effective and Most Efficient Pretrial Release Option,” Pretrial Justice Institute, 2013, https://perma.cc/US5H-MUFF. And one study based on Kentucky data showed incarceration for two to three days (as opposed to up to one day) — but ultimately being released pretrial — led to slightly lower rates of appearance in court. Christoper Lowenkamp, Marie VanNostrand and Alexander Holsinger, “The Hidden Costs of Pretrial Detention,” the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, 2013, https://craftmediabucket.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/PDFs/LJAF_Report_hidden-costs_FNL.pdf.

[16] The data includes all individuals released pretrial under any conditions. Administrative Office of the Courts, “Safety, Appearance, and Release Rates for Disposed Cases in Pretrial Interviews Released FY 18 Statewide by Charge County,” Research and Statistics, Nov. 27, 2018.

[17] Pretrial Justice Institute, “The Pretrial Services Agency for the District of Columbia.”

[18] Additional examples of bordering counties with contrasting rates of release pretrial with nonfinancial conditions include: Pike County (24%) borders Martin (68%) and Letcher (51%) (a 44 percentage point difference and a 27 percentage point difference). Todd County’s release rate on non-financial bonds is just 18% while Christian County, which it borders, has a rate of 57% (a 39 percentage point difference). Knox County’s release rate on non-financial bonds is 19%, compared to neighboring Whitley (45%) (a 26 percentage point difference). Laurel County’s release rate on non-financial bond is 14% versus Rockcastle (51%), Pulaski (48%) and Whitley (45%) (a 37, 34 and 31 percentage point difference). Anderson County’s rate of release on non-financial bond is 22%, Spencer’s is 24% and Washington’s is 29% — compared to neighboring Nelson County’s rate of 54% (a 32, 30 and 25 percentage point difference). Webster County’s rate is 16% versus neighboring Hopkins’s 42% rate of release on non-financial bond (a 26 percentage point difference).

[19] Kentucky Criminal Justice Policy Assessment Council, “Kentucky CJPAC Justice Reinvestment Work Group Final Report,” December 2017, https://justice.ky.gov/Documents/KY%20Work%20Group%20Final%20Report%2012.18.pdf.

[20] The risk assessment tool has been shown by research to be effective in predicting “failure to appear” and “new criminal activity”

rates. Matthew DeMichele, Peter Baumgartner, Michael Wenger, Kelle Barrick, Megan Comfort and Shilpi Misra, “The Public Safety Assessment: A Re-Validation and Assessment of Predictive Utility and Differential Prediction by Race and Gender in Kentucky,” April 25, 2018, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3168452.

[21] KRS 431.066, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=40904.

[22] Commonwealth of Kentucky Department of Public Advocacy, “Kentucky Pretrial Release Manual,” June 2013, https://dpa.ky.gov/Public_Defender_Resources/Documents/PretrialReleaseManualExternal102814REDUCED.pdf.

[23] In determining the amount of bail to set in the case of financial conditions of bail, a judge must consider several factors — not just the nature of the offenses charged against a defendant. KRS 431.525, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=39565.

[24] Stevenson, “Assessing Risk Assessment in Action.”

[25] Stevenson, “Assessing Risk Assessment in Action.”