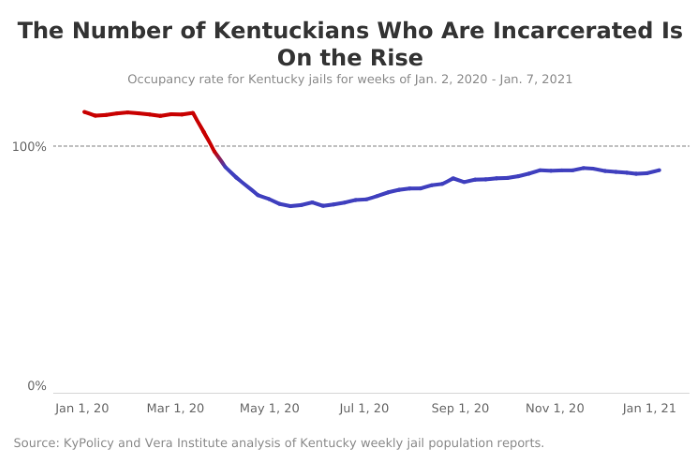

Between March and May of 2020, the jail population in Kentucky fell by a third (24,183 to 16,167) as a result of releases aimed at reducing the spread of COVID-19. Since May, however, the jail population has steadily increased statewide, posing a major risk for COVID-19 spread, which is already high in densely populated living spaces. Kentucky must work to reduce, not increase, the number of people who are incarcerated, as well as implement needed interventions to protect incarcerated Kentuckians during the pandemic.

After steep decline in incarceration, the numbers are rising again

Kentucky saw a significant reduction in its incarcerated population last year through several executive orders that commuted sentences and through expanded administrative release for people incarcerated pretrial. Overall, Kentucky jails held 8,016 fewer people between March and May, a decline of 33%, finally reaching a low of 16,167 on May 14. However, after this steep, two-month decline, Kentucky began seeing a steady increase in the jail population, climbing to 19,443 by November 19 and mostly holding steady since. Meanwhile, the current state prison population was 22% lower at the end of January 2021 than it was at the end of February 2020.

While this is still just below Kentucky’s total capacity for jails and prisons (a welcome change from before the pandemic when jails were at 114% of capacity overall), high levels of incarceration are always problematic. All prisons and jail facilities, even those that aren’t over capacity, are at risk for incubating and spreading COVID-19 outbreaks. The virus spreads through airborne transmission, and jails/prison facilities are closed spaces where social distancing is not feasible. When jails are at or over capacity — a situation we may be headed toward — it greatly increases the risk of danger both for jail populations (people who are incarcerated and the staff) and surrounding communities.

While Jefferson and Fayette counties (the most populated counties) expectedly have the highest total number of individuals who are incarcerated, rural counties, particularly in eastern Kentucky, are where many of the jails with highest occupancy rates are located. Out of the 77 Kentucky counties with jails, 37 are at or above 100% capacity of their jail facility occupancy rate, with the top five counties being Bell (224%), Carroll (185%), Letcher (169%), Leslie (167%) and Perry (156%).

People incarcerated in county jails in Kentucky fall into three primary categories — individuals awaiting trial or serving a misdemeanor sentence in county custody, individuals serving Class C or D (the lowest level) felony sentences held for the state Department of Corrections (DOC), and individuals in federal custody held by local jails under a contract with the U.S. Marshals or Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

As shown in the graph below, while the number of people in state custody in county jails steadily declined from March to July and then mostly held steady (the state custody population on Jan. 7, 2021, was 19% lower than on March 5, 2020), the population held for county-level incarceration has increased significantly from its original sharp decline from March to May 2020, and is close to surpassing the state custody population. Meanwhile, the number of people in federal custody held in Kentucky’s county jails has increased by 12% from Jan. 2, 2020, to Jan. 7, 2021.

COVID-19 cases have been rampant in Kentucky jails and prisons

According to the Kentucky Department of Corrections (DOC), as of February 1, there have been 6,884 confirmed cases of COVID-19 among people incarcerated in state prisons and 925 confirmed cases among staff. There have also been multiple COVID-19 outbreaks reported at county jails, and a late January news report stated that there have been more than 3,000 people incarcerated in jails and 500 local jail employees diagnosed with COVID-19 since last year (a number that is almost certainly far higher given the incompleteness of the data as described in the article). There is no centralized reporting of outbreaks in jails, not even for the people held in county jails who are serving state sentences, so unfortunately the only public information available about COVID-19 infections in jails continues to be through local media coverage.

State needs to do more to reduce the jail population while prioritizing people who are incarcerated in its COVID-19 response

In the summer of 2020, Prison Policy Initiative released a report describing how Kentucky had received a D- rating overall for its response to COVID-19 in its jails and prisons, receiving higher marks for executive orders and for releasing daily state prison data but failing marks for not halting jail admission or making larger reductions in the incarcerated population, among other issues.

As the pandemic continues, Kentucky needs to implement centralized reporting on COVID testing, positive cases in county jails and prevention measures being taken in county jails. This data is critical for monitoring breakouts and protecting communities. Kentucky also needs to prioritize people who are incarcerated for COVID-19 vaccination due to their status as high-risk for medical reasons and because jails, like other densely populated living spaces such as long-term care facilities, are institutions with high levels of outbreaks. While corrections workers are currently being prioritized in the Kentucky Vaccine Phases provided by the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services, people incarcerated in jails and prisons are not.

Kentucky also needs to do more through administrative response and legislation to reverse the increase of the incarcerated population. The administration and local justice systems need to pursue more ways to reduce incarceration during the pandemic. And more data is needed to better understand the specific drivers of increased incarceration in county jails despite the implementation of expanded administrative release. In addition to making the expansion of administrative release permanent, longer-term sentencing reforms including increasing the felony theft threshold (such as through House Bill 126, which just passed through the House Judiciary Committee) and additional pretrial reforms are steps for reducing the incarcerated population over time.