A study recently published in the American Sociological Review validates efforts to strengthen investments in education, health and other key areas by cleaning up tax breaks for those at the top. The finding – that millionaires are unlikely to respond to tax increases by moving – is important for Kentucky, where our upside-down tax code (it asks the least of those with the most) has led to deeply underfunded investments.

Millionaires Are Less Likely to Move

The Stanford University authors of “Millionaire Migration and Taxation of the Elite: Evidence from Administrative Data” challenge the notion that wealthy people are highly mobile and move from state to state “shopping” for low tax rates. Instead, 13 years’ worth of tax returns for millionaires show they migrate less than the general population and in fact, the migration rate “drops steadily with income.”

A compelling explanation is the idea of “elite embeddedness:” those at the top have strong social and economic ties to the region in which they have succeeded financially – in other words strong “place-based social capital” that comes from years of relationship-building. That makes it difficult for millionaires to move including in response to increases in income tax rates. Demographically, those at the top:

- Tend to be the “working rich” who already have employment, whereas a key reason for migration is to pursue employment opportunities;

- Are generally further on in their careers, as opposed to recent college graduates who are beginning at lower income levels and among whom migration is more common;

- Are more likely to be married, have kids in school, own homes and businesses – additional factors that discourage migration.

Supporters of regressive or upside-down taxation may be able to point to examples of millionaires who leave states with more progressive state tax policies: certainly such anecdotal evidence exists, especially when the state in question is Florida, where a tropical climate and luxury accommodations draw wealthy migrants. But after applying rigorous statistical analysis to tax data to see whether millionaires nationally relocate from high-to-low-tax states, the authors conclude that millionaire tax flight occurs “only at the margins of statistical and socioeconomic significance.” That means Kentucky could increase taxes on the top and benefit from additional revenue for investments in schools, health and other important areas, without causing meaningful out-migration.

Another part of the study examines whether millionaires specifically along state borders cluster on the low-tax side. Cross-border studies provide certain “natural controls” for social, cultural, and environmental differences that help isolate the possible impact of tax difference from other variables. In other words, top earners can choose to live on either side of the border, and consequently in either state, without forgoing access to the common market, cultural life or climate. The study finds that millionaires neither locate consistently on the low-tax side of the border, nor do they relocate to the lower-tax side of the border in response to tax changes. These findings cast a shadow on the claim that Kentucky loses out to Tennessee based on our comparatively progressive tax structure.

We Could and Should Fix Kentucky’s Upside-Down Tax System

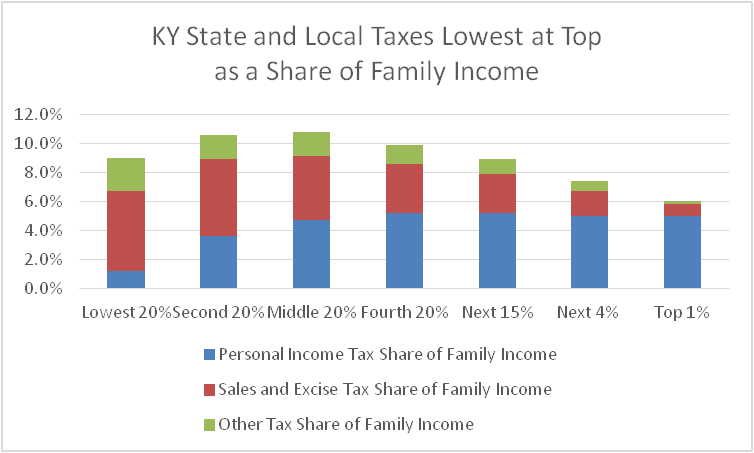

Kentucky’s tax system is less upside-down than Tennessee’s, but certainly has room for improvement. Though our incomes taxes are slightly progressive — rising as a share of income for the bottom four quintiles then leveling off at the top — our state and local tax system on the whole is regressive. Specifically, with billions of dollars in tax breaks and a top rate on income over $75,000 of 6 percent, our individual income tax is not sufficiently progressive to offset other regressive taxes, namely the sales tax. In 2015, the middle 20 percent of Kentucky earners (making between $30,000 – $50,000) paid 10.8 percent of family incomes in state and local taxes, while the top 1 percent (making more than $330,000) paid only 6 percent.

Source: Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy

This distribution is bad policy for a number of reasons:

- An upside-down tax system leaves money on the table that could be collected to support investments in a stronger state for everyone – without causing those at the top to flee.

- In an economy where an increasing share of growth goes to those at the top, asking the most of those for whom the economy is underperforming undermines fiscal health.

- Relying more heavily on low- to middle-income earners to fund services is bad for an economy driven by consumer demand, since they spend most or all of what they have on basic needs.

Cleaning up income tax breaks favoring those at the top would be an effective strategy to turn our tax code right-side-up and generate revenue for stronger public schools, college affordability, sustained investments in the health of our families and communities, modern and reliable infrastructure, great parks and a safety net that serves all Kentuckians in difficult times. The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy estimates that a 3.9 percent surcharge on millionaire’s income in Kentucky, for example, would generate $100 million in new revenue for these investments.