Last August, Kentucky applied to modify its Medicaid program through a request to the federal government to waive certain requirements of the law, known as an 1115 waiver. 1 As explained in our comments at the time, the proposed changes would result in fewer Kentuckians covered and therefore decreased access to health care, which would ultimately harm health and move the state backwards. 2 While the waiver proposal is framed in terms of increased financial sustainability and reduced costs, it would likely increase costs for the state as it introduces new, expensive and complex administrative burdens, and limits access to the preventative care that improves health and keeps costs down in the long run. Rolling back Kentucky’s historic gains in health care coverage would hurt the many Kentuckians who benefit from the state’s Medicaid program in its current form and act against the goals of the Medicaid program as a whole and the 1115 waiver in particular.

With the recent modification of the original waiver request comes added barriers to getting and using Medicaid coverage. By jumping from a 12 month phase-in of the community engagement component to an immediate 20 hour per week requirement, the enrollment losses would be even more severe. And by enforcing a reporting requirement on income changes with a six-month lock out for non-compliance, the program would penalize enrollees simply based on the nature of low wage work. These changes intensify the harms of an already counterproductive waiver.

Work Requirement Is Misguided and Harmful — and Change Makes It Worse

The original waiver request required a community engagement requirement that made eligibility for Medicaid coverage conditional on 20 hours a week of some work-related activity. This minimum hourly work requirement was to be ramped-up over a period of 12 months, but the operation modification changes that to an immediate 20 hour mandate. Embedded in the work requirement is the assumption that people covered by Medicaid are not working, or would be encouraged to increase their work by the requirement, with the goal of having their incomes rise above the level that makes them eligible for Medicaid. This assumption is wrong-headed, as it ignores the reality of low-wage work and the barriers to improved employment.

Most Medicaid enrollees who can work do work

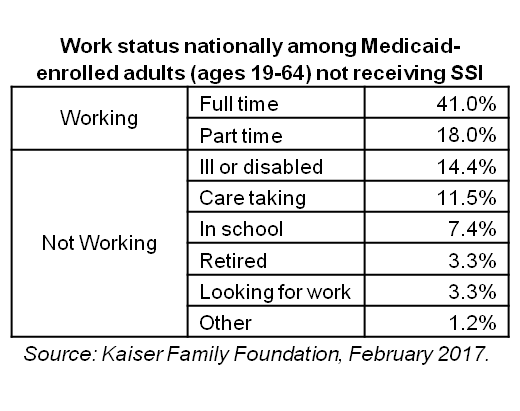

In Kentucky, the majority of Medicaid expansion enrollees currently work, and four out of five adult Medicaid expansion enrollees have worked at some point in the past five years. 3 The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that 51 percent of Kentucky Medicaid-covered adults currently work, and 66 percent come from a family where at least one person works. 4

Of those who do not work, most are ill or disabled, taking care of a loved one, or are in school or retired. Kaiser estimates that, nationally, all but 4.5 percent of Medicaid-enrolled adults are working or meet one of those criteria. Of the 4.5 percent who either do not work or have a good reason not to, 3.3 percent are looking for work and just 1.2 percent are not.

Work requirements ignore the nature of low-income work

Work requirements ignore the nature of low-income work

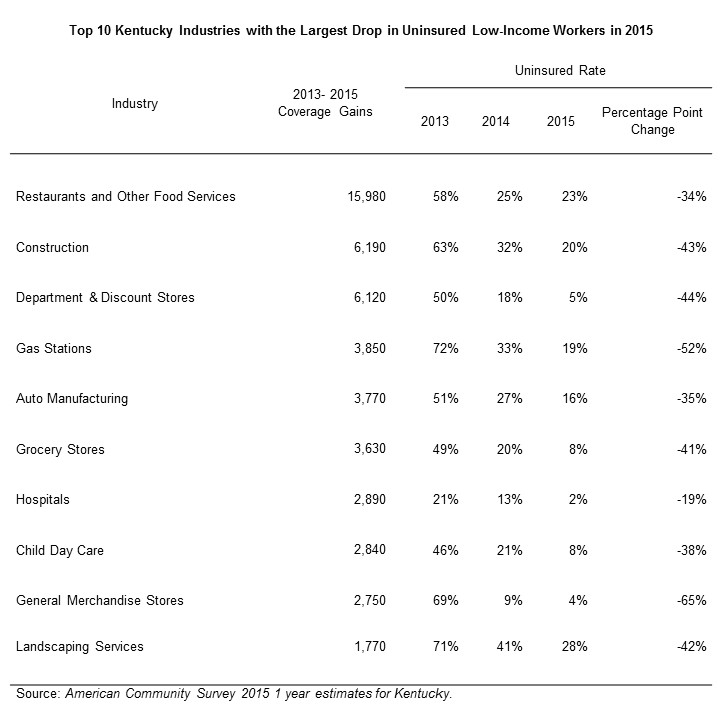

hours, sometimes below 20 hours per week. In fact, according to 2015 Census data, 1 in 5 non-elderly Kentucky adults whose incomes qualify them for Medicaid work less than 20 hours per week. 5 As of 2015, the three industries that employed the most Medicaid expansion-eligible adults in Kentucky were restaurants, construction and department stores, all of which often provide only part time and sometimes irregular work opportunities. 6

Estimates from the Kaiser Family Foundation mentioned above showed, nationally, 41 percent of Medicaid-covered adults work full time and 18 percent work part time. Low-income workers often are forced to work fewer hours than they would prefer. According to the Department of Labor, over 5 million Americans work part time involuntarily and would work more if their place of work offered more hours or they could find full time jobs.7

Work requirements do not promote long-term employment or reduce poverty

An established body of research shows work requirements do not reduce poverty or succeed in helping people obtain long term, permanent employment. 8 Among those who received cash assistance through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) since its creation in 1996, work requirements have not yielded long-term results. One review of 13 randomly assigned studies showed a work requirement resulted in a short-term increase in employment, but employment outcomes faded after 2 years and the requirement didn’t have any effect on employment 5 years afterward. In fact, the study showed most participants were not employed 75 percent or more of the time, 3 to 5 years out from their participation in TANF-required work activity. 9 The communities that have shown significant long-term employment effects through a program that required work as a condition of eligibility were in Portland, Ore., and Riverside, Ca.. In those communities program administrators offered significant work supports and training, and encouraged participants to hold out for better jobs with higher wages that offered more opportunity for advancement.

Most individuals subject to work requirements remain in poverty, and in some cases become poorer. An evaluation of 11 programs that offered cash assistance and SNAP (formerly known as food stamps) showed that the percent of TANF participants living in poverty in the observed communities didn’t change 2 years after participation, and the percent living in deep poverty (half of the poverty level or less) increased in 6 of the 11 communities. 10

Work requirements are ineffective as a condition of eligibility for public benefits because they do nothing to change either an individual’s job qualifications, ability to afford job training and education or the existence of decent job opportunities in the labor market in which he or she is trying to navigate.

Work requirements would result in decreased enrollment

In the recent request to add a work requirement nearly identical to the one Kentucky has proposed, the Indiana Family and Social Services Administration estimated that a quarter of those for whom a work requirement would apply would lose coverage due to non-compliance. 11 Assuming our state’s Medicaid population is similar, this requirement alone could lead to roughly 100,000 people losing coverage because they would not be able to meet the requirement for various reasons.

Those reasons do not have to do with a lack of motivation, or a desire to “free-load” as some have suggested, but are due to a struggling labor market. Between 2009 and 2017, 32 Kentucky counties saw the total number of jobs decline 10 to 32 percent. Roughly 3/4 of Kentucky counties saw either modest job growth of less than 10 percent or a decline in jobs during that time frame.12 A depressed labor market in much of the state, barriers to gainful employment or advancement like criminal records and poor health, and a lack of income supports and adequate wages are primarily what is holding back unemployed and underemployed Medicaid enrollees from better economic mobility. 13

Removing the ramp-up for community engagement hours would exacerbate the damage

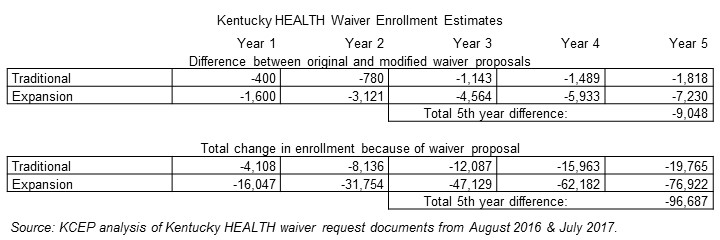

By eliminating a 12 month ramp-up for community engagement and instead requiring an immediate 20 hour per week activity related to work, the state would be enforcing a mandate without any opportunity for participants to adjust to it. Although the waiver amendment request includes a three month delay in the requirement, primarily for first time enrollees, enrollment would decline even more substantially than under the original waiver. In the estimate provided within the public notice section of the operational modifications document, it is estimated that 9,048 more people would lose coverage than under the original waiver request. A total of 96,687 would lose coverage by the 5th year. According to the estimate, people would lose coverage “for a variety of reasons, including program non-compliance.” In other words, rather than strengthen and expand coverage for low-income individuals, as is the first of four criteria for an 1115 waiver, these changes do the opposite.

Locking Out Medicaid Enrollees for a Failure to Report Changes in Income Is a Penalty for the Nature of Low-Income Work

There is already a requirement that enrollees report changes in wages that bump them over the income eligibility threshold. But the proposed change penalizes a failure to report a much larger number of changes, with failure to comply resulting in a six month lockout from the program. Now changes that must be reported include changes in income that affect thresholds to pay different levels of premiums (25, 50 and 100 percent of the Federal Poverty Level), changes in an employer’s health insurance offerings and premium costs, and changes in work-related hours per week. This requirement punishes people solely on the volatile nature of low-wage work.

Medicaid workers work in industries with instable hours and income

As mentioned previously, Kentucky workers covered by Medicaid work in jobs with irregular hours and inconsistent wages. This is especially true for the three industries with the largest Medicaid populations: restaurants, construction and retail. In retail, hours change weekly or even day-of; restaurant workers depend on tips, which vary greatly, especially when shared; and construction work is seasonal and often depends on weather conditions as well as the location of construction projects.

Low-wage workers face a number of challenges that would make this reporting requirement onerous. According to the Center for Law and Social Policy, many low-income workers are employed in jobs that have:

- Inadequate hours.

- Highly variable hours on a weekly basis.

- Little advance notice of shifts, including being sent home early or called in right before a shift begins because of growing use of management strategies like “just-in-time” scheduling.

- Split shifts or on-call shifts. 14

In each of these cases, wages and hours would vary on a week-to-week basis. But the waiver modification states such changes would have to be reported to the cabinet within a 10 day period. This would be burdensome for both the enrollee and the state, and would almost certainly result in people churning on and off Medicaid and higher administrative burden.

Locking out Medicaid enrollees for a failure to report income would increase churn and disrupt care

As already mentioned, given the highly variable work schedules and income of Medicaid-covered workers, it is very likely many Medicaid enrollees will become locked out of coverage. That results in one of two things: Either enrollees would decide to go without coverage and forgo needed care, or they would seek out a financial or health literacy class so they can re-enroll. In either case, this would be burdensome for the state and disruptive for the individual.

People already churn in and out of Medicaid in Kentucky at a high rate. Between 2012 and 2013, 19 percent of the Medicaid population changed eligibility status. 15 Each time someone’s eligibility status changes it requires administrative action. The prospect of a large number of people becoming locked out of Medicaid and then moving back on, potentially the same day, multiple times a year would dramatically increase the administrative cost and burden for the state.

In addition, disruptions in care could have very serious consequences for individuals with chronic conditions. According to a study from the Harvard School of Public Health, 72 percent of Medicaid expansion-eligible Kentuckians have 1 or more chronic conditions. 16 The study also found a substantial increase in the number of low income Kentuckians with a primary care physician and getting regular care for chronic conditions, thanks to Medicaid expansion. The waiver will cause more of these people to cycle on and off coverage, reducing health and costing the state more in the long run as conditions that might not have worsened become more expensive to treat.

Build on Kentucky’s Health Care Successes – Don’t Undermine Them

Kentucky has made historic progress in health care, primarily through our decision to expand Medicaid. Several studies have shown that multiple measures of health access and outcomes have improved since 2014:

- The number of uninsured Kentuckians dropped by more than half.

- Screenings for cancer, diabetes and dental issues have risen dramatically.

- The number of people with a primary care physician and who are receiving regular care for a chronic condition have increased.

- Preventable hospitalizations for problems like hypertension and asthma have dropped.

- Breast cancer deaths and infant mortality have declined.

- There is an increase in Medicaid expansion-eligible Kentuckians who report having excellent health. 17

The 1115 Medicaid waiver process exists to demonstrate innovations in health care coverage and delivery that move us forward. In spite of our unparalleled gains in health, this process could be used to make even more improvements. In fact the goals of an 1115 waiver, according to the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services are:

- Increase and strengthen overall coverage of low-income individuals in the state.

- Increase access to, stabilize and strengthen providers and provider networks available to serve Medicaid and low-income populations in the state.

- Improve health outcomes for Medicaid and other low-income populations in the state.

- Increase the efficiency and quality of care for Medicaid and other low-income populations through initiatives to transform service delivery networks.

But the waiver request does not meet these standards, as we described in our prior comments, and those failures are worsened by the most recent round of modifications. The new barriers to coverage, administrative complexity and reduced benefits are in direct conflict with what a demonstration waiver should do.

Forcing people off health care coverage based on the nature of their work and the current state of the labor market impedes that progress and would ultimately harm our communities. We urge the state to abandon these changes and work with stakeholders across the commonwealth to shape our Medicaid program in a way that builds on, rather than rolls back, our successes.

- “Kentucky Health,” Kentucky Cabinet for Health & Family Services, August 15, 2015, http://chfs.ky.gov/NR/rdonlyres/69D38EB6-602F-4707-933C-80D5AAE907F7/0/KYHEALTHWaiverFINAL.pdf. ↩

- Dustin Pugel & Jason Bailey, “Proposed Medicaid Waiver Would Reduce Coverage and Move Kentucky Backward on Health Progress,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, October 7, 2016, https://kypolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/1115-Medicaid-Waiver-Federal-Comments-KCEP.pdf. ↩

- Dustin Pugel, “Many Kentucky Workers Have Gained Insurance through the Medicaid Expansion and Are Now at Risk,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, December 8, 2016, https://kypolicy.org/many-kentucky-workers-gained-insurance-medicaid-expansion-now-risk/. ↩

- Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz & Anthony Damico, “Understanding the Intersection of Medicaid and Work,” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, February 17, 2017, http://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/understanding-the-intersection-of-medicaid-and-work/. ↩

- Data are from the 2015 American Community Survey one year estimates for Kentucky adults under 64 years old who earn less than 139% of the Federal Poverty Level. ↩

- Pugel, “Many Kentucky Workers Have Gained Insurance through the Medicaid Expansion and Are Now at Risk.” ↩

- Data are from the Current Population Survey’s June 2017 estimate for workers in nonagricultural industries who worked part time for economic reasons. https://www.bls.gov/webapps/legacy/cpsatab8.htm. ↩

- LaDonna Pavetti, “Work Requirements Don’t Cut Poverty, Evidence Shows,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 7, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/6-6-16pov3.pdf. ↩

- Jeffrey Grogger & Lynn A. Karoly, Welfare Reform: Effects of a Decade of Change, Harvard University Press, 2005. ↩

- Stephen Freedman et al., “National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies: Two-year Impacts for Eleven Programs,” Manpower Development Research Corporation, June 2000, http://www.mdrc.org/publication/evaluatingalternative-welfare-work-approaches. ↩

- “Amendment Request to Healthy Indiana Plan (HIP) Section 1115 Waiver Extension Application,” Indiana Family and Social Services Administration, July 20, 2017, https://www.in.gov/fssa/hip/files/HIP%20Amendment%20(Update%207_20).pdf. ↩

- Jason Bailey, “Job Recovery for Some Kentucky Counties, Second Recession for Others,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, May 15, 2017, https://kypolicy.org/job-recovery-kentucky-counties-second-recession-others/. ↩

- Jason Bailey, “Address Declining Workforce through Job Creation and Work Supports,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, July 11, 2016, https://kypolicy.org/address-declining-workforce-job-creation-work-supports/. ↩

- Jessica Gehr, “Doubling Down: How Work Requirements in Public Benefit Programs Hurt Low-Wage Workers,” Center for Law and Social Policy, June 2017, http://www.clasp.org/resources-and-publications/publication-1/Doubling-Down-How-Work-Requirements-in-Public-Benefit-Programs-Hurt-Low-Wage-Workers.pdf. ↩

- Anita Cardwell, “Revisiting Churn: An Early Understanding of State-Level Health Coverage Transitions Under the ACA,” National Academy for State Health Policy, August 2016, http://nashp.org//www/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Churn-Brief.pdf. ↩

- Benjamin D. Sommers, Bethany Maylone, Robert J. Blendon, E. John Orav & Arnold M. Epstein, “Three-Year Impacts Of The Affordable Care Act: Improved Medical Care And Health Among Low-Income Adults,” Health Affairs, May 17, 2017, http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/early/2017/05/15/hlthaff.2017.0293. ↩

- Dustin Pugel, “New Report Highlights Kentucky’s Gains in Care and Health,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, March 17, 2017, https://kypolicy.org/new-reports-highlight-kentuckys-gains-care-health/. ↩