A recent state Supreme Court ruling has threatened the operation of thousands of slot machines across Kentucky because they do not meet the definition of “pari-mutuel wagering” associated with the lawful conduct of horse racing in Kentucky. The General Assembly may attempt action to keep these machines in business in the upcoming legislative session.

If so, the legislature should ensure these slots are appropriately taxed, like in other states, instead of maintaining the deeply inadequate tax levels Kentucky now allows. Doing so could raise at least $60 million annually in additional state revenues for investments in schools, health and other vital services.

“Historical horse racing” machines are simply slot machines

Starting in 2010, Kentucky began allowing a form of gambling that the industry markets as “instant racing” or “historical horse racing.” Despite the name, this type of gambling in fact bears no resemblance to horse racing. It features electronic terminals with names like “Money Harvest” and “Enchanted Treasures” where players spin to win like any other slot machine. The industry attempted to make a tenuous connection between the machines and horse racing by using the outcomes of randomly generated past races as the basis of spin results, but bettors typically have no awareness of that connection.

Proponents implausibly claimed these machines were legal under Kentucky law because they constituted “pari-mutuel wagering.” But under that system gamblers bet in pools against each other on discrete, individual live events, and those pools set the odds and payouts for each event. In a unanimous decision in September following 10 years of litigation, the Kentucky Supreme Court ruled that this is not how these machines work.

Instead, the industry itself creates the initial betting pool and must replenish it periodically, and patrons in effect wager on multiple anonymous races across history as opposed to simultaneously betting on a single race. That means patrons are not wagering among themselves, as required for pari-mutuel wagering. “Instant racing” was essentially an elaborate attempt to get around the laws prohibiting casinos in Kentucky, but the court has now struck it down.

Slot machine casinos are growing rapidly across Kentucky

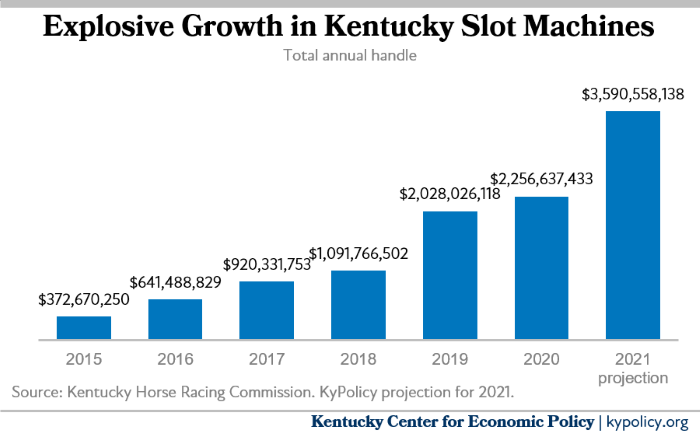

These slot machines have been expanding rapidly across the state, and the growth is expected to continue in the future. The handle, or the amount of money bet through these machines, topped $1 billion in 2018. After revenues stopped for a few months in 2020 as the casinos were shuttered temporarily during the COVID-19 crisis, betting at these machines resumed rapid growth in recent months. Based on receipts through November, the industry is on pace for $3.5 billion in handle at these facilities in the current fiscal year.

Currently, there are 3,527 such machines operating at facilities across the state, with an average daily handle of $9.8 million. In addition, the Kentucky Horse Racing Commission has approved thousands more machines, meaning the numbers are expected to rise further the future. We outlined the growth and expansion of these facilities across the state here.

Kentucky’s slot machines are taxed at a fraction of levels in other states

While betting at these facilities has grown dramatically in recent years, the amount collected for the state’s General Fund has been very small because the state taxes them at extremely low rates — far less than slot machine casinos in other states.

Typical tax rates at casinos are significant because they take into account the social costs associated with gambling. Rates often range from 25% to 50% or more of gross gaming revenue (generally defined as the amount that remains after paying winning bets, which is comparable to gross commissions in Kentucky’s system). Electronic gambling devices are often taxed at higher rates — for example, at 55% in Pennsylvania and 53.5% in West Virginia.

However, Kentucky’s tax on instant racing slot machines is much lower. In 2020, these machines brought in $189 million in gross commissions for the industry, but the state’s excise tax collected only $34 million — an effective tax rate of only 18%. But the story for Kentucky’s budget is actually even worse, because most of that revenue goes right back to the industry to support purses and other industry endeavors. The actual amount collected for Kentucky’s General Fund in 2020 was only $15 million, or an effective tax rate of only 8%. That’s what attorney Stan Cave called “the greatest ripoff in the history of the state of Kentucky” in testimony to the General Assembly’s Interim Joint Committee on Licensing and Occupations.

As we have noted previously, if Kentucky simply taxed these slot machines at a rate on par with what we tax live horse racing handle at the same volume (which would constitute a rate of approximately 32% of gross commissions for the General Fund, and 42% counting what goes back to the industry, a rate still far below what many other states levy), we could raise substantial additional revenue for the state’s General Fund. Based on the amount of betting we’ve seen so far this fiscal year, Kentucky could generate at least $60 million more a year — a number that will grow further as additional machines are installed.

Kentucky’s schools, health and more shouldn’t continue to be shortchanged

For a long time, Kentucky’s politics have been entangled in debates about whether to allow casino gambling. While that debate was in gridlock, the gambling industry was proceeding to rapidly site instant racing slot machines throughout Kentucky — a backdoor method that has resulted in the proliferation of mini-casinos all across the state. Because they did so without first passing the necessary legislation, their efforts have now been halted by the Kentucky Supreme Court.

If Kentucky decides to allow these facilities to operate in the state, we must not let the state’s budget continue to be shortchanged by meager tax rates. Gambling profits shouldn’t be allowed to continue growing dramatically on the backs of Kentucky’s economy while critical investments in schools, infrastructure, health and more fall further behind.