The expanded $300 a week in federally-funded jobless benefits known as Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) is providing a necessary bridge for families and the economy as we begin to emerge from the COVID-19 economic crisis. The benefit has added an average of $19 million a week in federal dollars into Kentucky’s fragile economy, spurring business growth as people spend those dollars in communities and shoring up family budgets during a time of continued severe hardship. Claims that FPUC is a major barrier to hiring workers are not based in evidence. Kentucky must fully protect the benefit through its federally–authorized expiration in early September and ignore calls from a few to hamper our recovery and hurt ailing workers by eliminating it.

Extra federal money helps spur demand and boost jobs

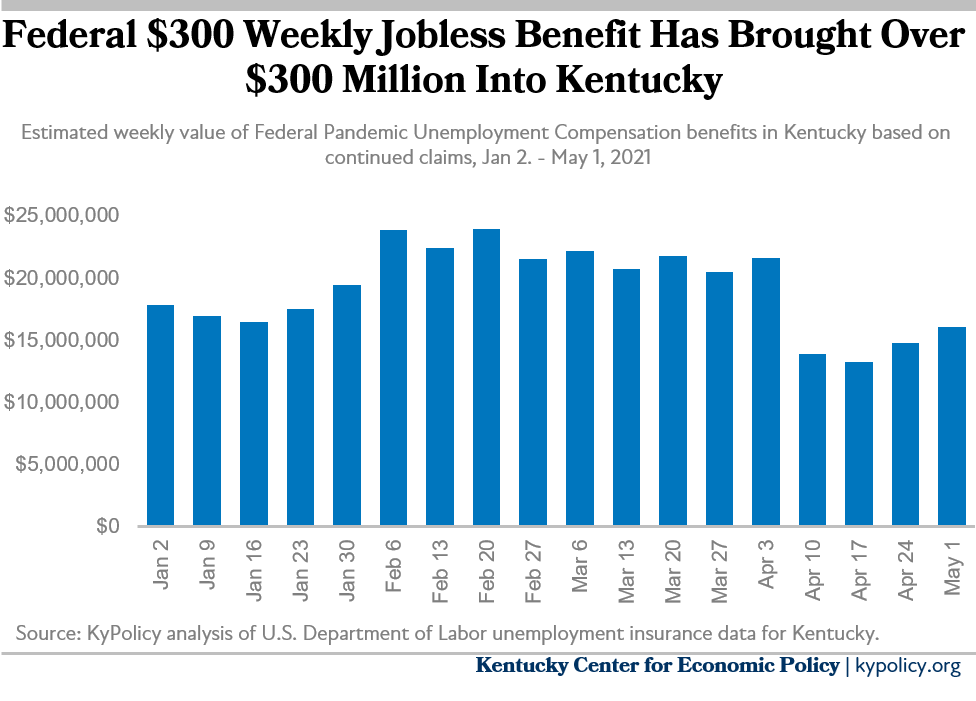

Since FPUC was reinstated by the relief package passed by Congress in December, it has brought an estimated $344 million into Kentucky, and nearly $4 billion since the beginning of the pandemic. This money was then used by claimants to pay for their everyday needs like groceries, utilities and transportation — spending that in turn supports businesses and jobs as it flows through the economy.

If Kentucky were to get rid of the $300 a week in benefits it would cost the state an estimated $229 million and hurt our economy as people would necessarily buy fewer goods and services. Last summer, when Congress allowed the larger $600 version of FPUC to expire, the Economic Policy Institute estimated that that loss in demand could have cost Kentucky nearly 50,000 jobs. Since then, the number of claimants has fallen dramatically, and the benefit has been halved, but the funding still supports employment through higher levels of consumer spending. Additionally, because FPUC is a federally-funded benefit, all of this money comes from out of state and costs Kentucky businesses and Kentucky state government nothing.

Kentuckians are returning to work

Over the last year, the number of Kentuckians receiving unemployment benefits has fallen dramatically while the number of people employed has been rising. Nearly 200,000 net jobs have been filled since the worst point in the crisis last April, and the number of Kentuckians receiving unemployment benefits is now just 18% of what it was at that time.

Yet some are claiming that the extra $300 in benefits is keeping people from working. Careful academic research on the much bigger $600 benefit last year found it had little to no impact on employment.

Most of the complaints about an alleged labor shortage come from restaurants offering low wages, few benefits and little workplace flexibility. Even with the limited appeal of restaurant work, people are returning to those jobs in huge numbers: 40,600 more Kentuckians work at restaurants now than at the worst point in the COVID recession. That sector faces two remaining barriers. It shed nearly 40% of its employment during the crisis, and it is taking time to build back that workforce even as customers return to restaurants after getting vaccinated and as COVID cases fall. And some restaurants insist on continuing to offer low wages at a time when workers still face barriers to employment including care responsibilities and health problems. Those businesses can attract more workers by offering competitive compensation and more accommodations.

Cutting off the $300 will hurt a wide range of workers who are receiving a benefit they need at a time when the economy is still struggling. Only 10% of Kentucky workers receiving state unemployment benefits in March had worked in the accommodation and food services sector, which is generating most of the attention. In fact, manufacturing and construction are the two Kentucky industries with the most workers who would lose jobless benefits if they were prematurely cut off. Over 14,000 self-employed workers and business owners who lost their income in the crisis and are receiving Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) would also lose the $300 weekly supplement.

Cutting off the $300 in supplemental benefits would also widen existing inequities and put up new roadblocks for Kentuckians already facing disproportionate harms from the pandemic. Black Kentuckians, for example, make up 13.1% of laid-off Kentuckians currently receiving unemployment benefits, a larger share than their 9.8% of the workforce.

Kentucky should continue to administer the federal benefit as long it is available

Last summer when the $600 per week version of FPUC expired, we heard from dozens of Kentuckians about how their hardship was exacerbated without that income support. While COVID-19 cases are falling and more Kentuckians are getting vaccinated, the pandemic isn’t over yet and the economy has a long way to go until it is back to pre-pandemic conditions. Kentucky still has 98,100 fewer jobs than before COVID-19 hit, and nearly 1 in 3 Kentucky adults report difficulty covering usual household expenses.

While the economy is getting back on its feet, Kentucky should not remove this critical economic boost. Many of the Kentuckians still receiving unemployment benefits were recently laid off or are immunocompromised, recovering from long-COVID, looking for a job in fields where opportunities are still scarce and shouldering child and elder care responsibilities. And moving forward, we should learn from the lessons of this downturn and improve our state unemployment insurance system so that it works better for laid-off Kentuckians in the future.