Kentucky has one of the worst rates of incarceration in the country. Two years after a sharp decline in the Kentucky jail population due to COVID-19 policy-driven releases, the state’s jails are now over capacity again, with 21,831 people incarcerated in jails at the end of April, along with an additional 9,835 people incarcerated in state prisons.

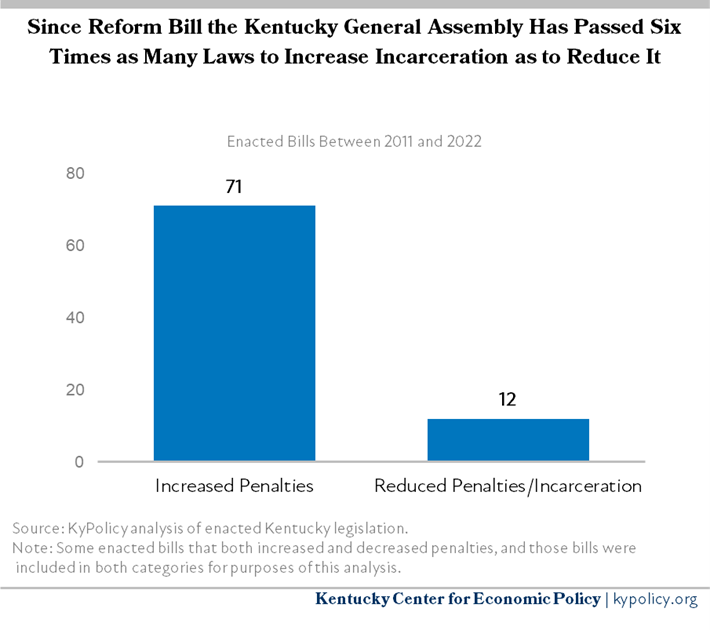

This legislative session, the General Assembly did not do enough to address this problem, and likely made it worse. Following the 2021 session that saw the passage of bills intended to modestly reduce incarceration and related harms, there was hope for further progress in the 2022 General Assembly. Instead, the legislature continued the broader trend of enacting significantly more bills that increase incarceration than decrease it. The General Assembly passed 12 bills that increase existing penalties or create new penalties and only 2 bills that should help to reduce incarceration.

Fewer bills passed that attempt to reduce incarceration than increasing it

Of the good bills that passed, Senate Bill (SB) 90 aims to reduce incarceration and criminal system involvement by implementing a 10-county, 4-year pilot “conditional dismissal” program that diverts people with mental health and substance use disorders who meet the eligibility requirements from the court system, instead providing supports and services in the community for these individuals. The restrictive eligibility requirements included in the bill will significantly limit the number of people who can be helped by this program, as will the fact that the program will be available in only 10 counties (which have yet to be determined). The bill requires the collection of a significant amount of data that will allow for review and evaluation of the effectiveness of the program, and should be used to guide the creation of a statewide, more inclusive program. People who successfully complete the program will have their criminal charges dismissed.

House Bill (HB) 310 expands time served credits for pretrial home incarceration to people who are ordered to pretrial detention without a GPS monitor. Prior to this legislative session, these individuals did not get credit for time served, or credit toward any potential future jail sentence. By expanding the number of people who receive credit for time spent on home incarceration pretrial, this change will ultimately reduce the amount of time people spend incarcerated following conviction.

Those 2 positive new laws are meager in comparison to 12 new laws that expand or enhance existing crimes, or create new crimes. Since 2011, the General Assembly has now passed 71 such bills, compared with only 12 bills to reduce penalties or incarceration.

Of the bills, two are particularly concerning because of the potential number of people impacted and the increased corrections costs. One such bill is HB 215, which does not create a new crime, but instead significantly increases already harsh penalties on existing crimes. HB 215 requires any individual convicted of importing or aggravated trafficking of carfentanil, fentanyl or fentanyl derivatives to serve at least 85% of their sentence before being eligible for release — an increase from the current requirement that such individuals serve at least 50% of their sentences. Additionally, HB 215 prohibits pretrial diversion for anyone charged with one of these offenses. Because the definition of importing in the bill includes the selling or sharing of any quantity of carfentanil, fentanyl or fentanyl derivatives to another person, with or without compensation, people who are low-level users sharing with others can be charged with these harsh penalties, even if they never sell anything to anyone.

SB 179 enhances penalties one level for existing crimes relating to assault, burglary, criminal trespass, criminal mischief, theft and robbery if the crimes are committed in an area where there is a declared emergency caused by a natural or man-made disaster that “imposes a significant threat to human health and safety, property, or critical infrastructure.” Research shows that enhancing criminal penalties does not actually prevent crime or make communities safer, and in the wake of a disaster, would only pile on to desperation in ravaged communities.

While the remainder of the 12 bills don’t have the same significant projected incarceration impact individually, they all take us in the wrong direction and continue pushing Kentucky down the path of increased incarceration.

Pretrial bills, both good and bad, did not move

Kentucky’s pretrial system — which determines whether a person charged with a crime waits for their day in court behind bars or at home — is arbitrary, unfair and unjust. It is a system where people who have money can get out, and people who do not cannot. Research shows that pretrial incarceration is associated with numerous harms to individuals and families while failing to make communities safer. Individuals who remain incarcerated pretrial are more likely to lose a job, plead guilty even when innocent and be found guilty if their cases do go to trial. However, 3 bills were introduced in the Kentucky General Assembly that would have actually increased pretrial incarceration and exacerbated the injustices in the current system.

One good pretrial bill that received a committee hearing but otherwise did not move was SB 31, which would have required that — with a few exceptions — individuals detained pretrial have their case tried within 180 days for a felony charge or 90 days for a misdemeanor charge. While the bill would not have reduced the number of people who are detained pretrial, it would have reduced the amount of time people can legally be detained before trial. Additionally, SB 31 would have limited the amount of time an individual may spend in pretrial detention to the maximum term of imprisonment for the most serious charge that has been made against them (if the offense charged is a felony). Currently, some Kentuckians are being detained pretrial for longer than they could be sentenced to at trial.

Fortunately, HB 313 and SB 313, which would have placed significant restrictions on the operations of charitable bail funds — such as restricting the bail amounts these organizations can post to very low amounts and for only certain charges — did not move either. Charitable bail funds provide bail and other support services to people who cannot afford them, providing one of the only ways for Kentuckians in these circumstances to avoid wealth-based detention. Restricting charitable bail funds’ ability to respond to unjust wealth-based detention would only exacerbate the systemic inequities in our pretrial system.

Other missed opportunities to reduce incarceration and support reentry

Many bills filed this session that would have addressed some of the most inequitable provisions in our criminal laws did not move either, creating a missed opportunity to address Kentucky’s severe level of incarceration. HB 776 would have significantly changed the way our systems address substance use disorders by establishing harm reduction centers, imposing community service and participation in educational programming as the punishment for possession of a controlled substance, and providing for setting aside of prior convictions for possession. HB 136 would have legalized medical cannabis, and HB 521 would have authorized and regulated the sale and purchase of non-medical cannabis in Kentucky.

Several bills were also filed to address Kentucky’s Persistent Felony Offender (PFO) law, a punitive sentencing policy that provides prosecutors with the option of enhancing sentences for people convicted of a felony if they have previously been convicted of any felony offense. SB 333 would have allowed PFO to apply only if a person is charged for a crime under the same section of the Kentucky Revised Statutes they were previously convicted of violating. SB 379 would have allowed juries to decide whether to apply PFO statutes rather than making the application mandatory as it is under current law. The bill would have also removed a 5-year look back for a prior conviction, expanded the availability of probation or conditional discharge to nonviolent C felonies (under current law, these provisions apply to D felonies only), and, applied retroactively, SB 380 would have removed PFO in the 2nd degree.

Finally, SB 163, an education bill that was vetoed, originally attempted to expand educational opportunities for formerly incarcerated people by allowing them to access Kentucky Educational Excellence Scholarship (KEES) funding earned prior to their incarceration. But the final version of this bill included harmful provisions that instead would have reduced educational opportunities available for current and formerly incarcerated individuals — the exact opposite of the original intent of the bill. It would have placed a lifetime ban on state scholarships through the need-based College Access Program and Work Ready Scholarship, among others, for people with convictions for violent offenses or criminal offenses against a minor. And it would have placed an additional ban on these programs while people are incarcerated for certain trafficking or importing offenses. Need-based financial aid is an important tool for increasing college degree and credential attainment among low-income Kentuckians. Higher education has been shown to reduce recidivism, and currently 41% of Kentuckians leaving incarceration end up returning after 2 years.