Click here to view a pdf of the report.

There has been a substantial decline over the last several decades in the share of employment that can be described as “good jobs” (defined in terms of salary, health and retirement benefits that allow an employee to make ends meet while still saving for the future) in the U.S. economy.1

Wages are stagnant for many workers and employer sponsored benefits including paid leave (i.e., for sickness and vacation) are becoming less common. In addition, wage theft is on the rise and new scheduling practices make work difficult for many employees.

Considering this context, it is concerning Kentucky’s workforce development conversations focus almost exclusively on employers’ needs and perspectives and ask how public dollars can improve perceived deficiencies in the workforce. Such an approach ignores the increasingly difficult conditions employees face in the labor market, and the responsibilities employers should have to provide jobs that meet acceptable community standards.

Workforce Development Investments in Kentucky

Our state’s workforce development strategy is being built around what employers say they need, with a focus on training workers in five occupational areas considered to be in high demand: advanced manufacturing, health care, construction, transportation/logistics and business/IT.2 While the administration, including the Education and Workforce Development Cabinet, acknowledges the importance of decent wages — with these sectors being touted as providing jobs that pay an average salary of around $40,000 a year — job quality is otherwise absent from state workforce development conversations.3

Here is an outline of several of the state’s key workforce development strategies that illustrate the administration’s employer-centered approach:

- Through the Kentucky Work Ready Skills Initiative, the state has spent nearly $100 million over the past two years on equipment and facilities needs for training programs in the five occupational areas across the state. These projects are collaborations between secondary education institutions, postsecondary education and industry — although very little public information exists on which employers are involved. It is also unknown how much potential employers plan to compensate entry-level employees that are trained using public dollars as well as other aspects of job quality.4

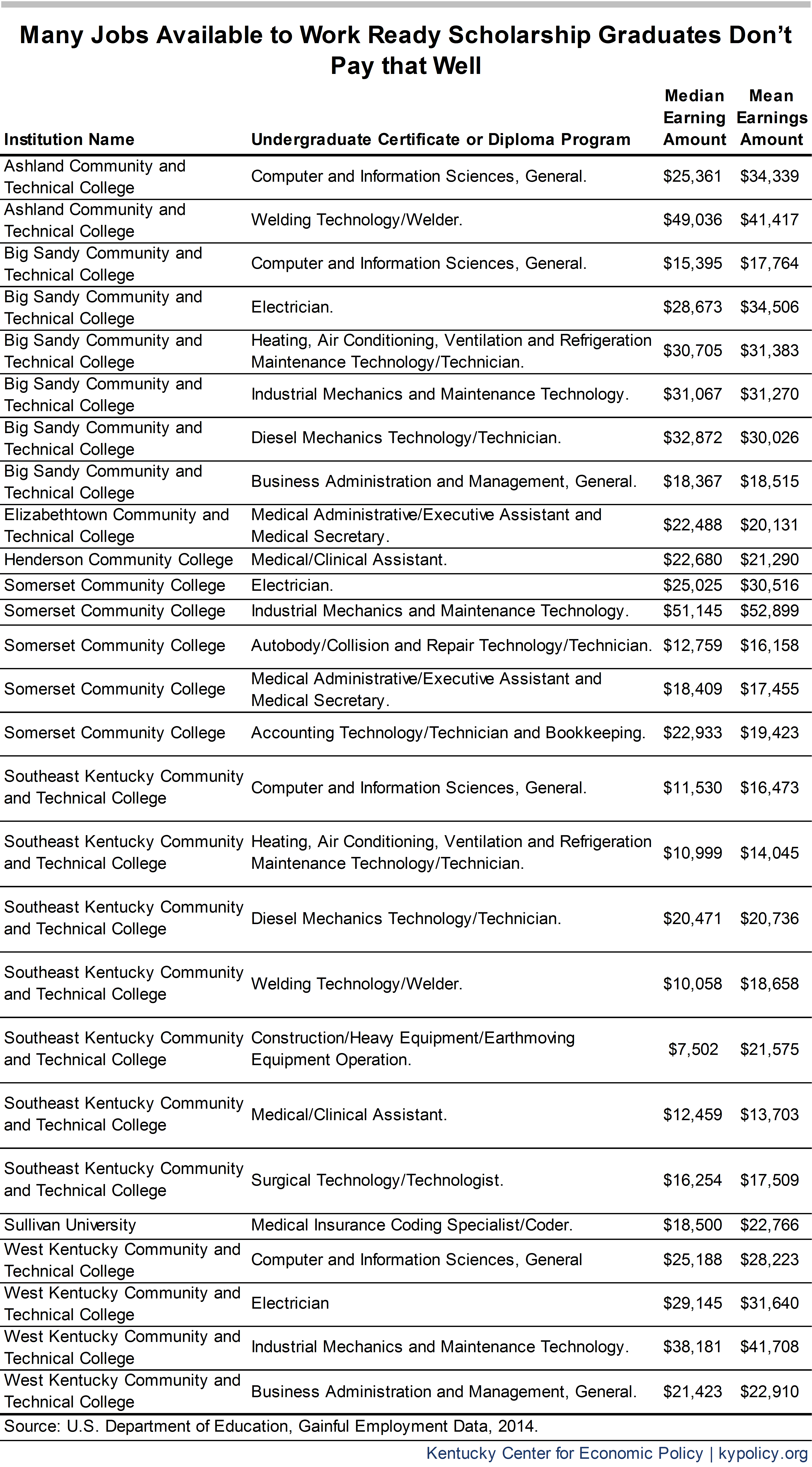

- The new Work Ready Scholarship program, which began this year, pays for tuition and mandatory fees at a state community college for Kentuckians to earn a short-term certificate or diploma credential (but not an associate’s degree) in any of the five occupational areas, with employers providing input into curricula and other aspects of these programs. The scholarship can be used at qualifying programs at several of the state’s public universities, two private universities (one of which is a for-profit) and schools in the Kentucky Community and Technical College System.5 It should be noted that at the same time the state is investing in these short-term credentials it is disinvesting in the public postsecondary education system.6

- Kentucky also receives federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) funds for training young and displaced workers, among others. The state’s WIOA plan is framed largely in terms of meeting employers’ stated needs.7 Employers benefit from WIOA funds both directly and indirectly; in some cases WIOA funds pay qualifying workers’ salaries for a period of time through on-the-job training and in other cases WIOA funds are used to train workers specifically for jobs with certain employers.

- Kentucky communities are becoming certified “work ready” and some public K-12 school districts — and legislators — are working to similarly certify secondary education students through a “work ethic certificate,” which involves voluntary drug testing and very few absences from school, among other criteria.8 In contrast, there is not currently a movement to similarly certify employers as high quality.

Making investments in workforce development based almost exclusively on what employers say they want or need is problematic in a labor market where, due to lack of policies upholding job quality, many jobs do not compensate workers enough to support stable employment, economic security and opportunity, and robust local economies. In such a context, the almost unilateral focus on employer needs can not only hurt workers but also ultimately undermine employers’ own best interest in a healthy, productive workforce and thriving communities.

Job Quality Concerns

Job quality is rarely mentioned in our state’s workforce development agenda but should be a central concern. The quality of jobs has been declining nationally and indicators suggest Kentucky workers are experiencing these national trends. When state leaders generically describe the many employers who are looking for qualified workers, the quality of these employers — which is likely quite variable — often is not specified.

Wages and Benefits

Kentucky is often described as having a “skills gap,” meaning there are plenty of good jobs but not workers with the skills and capabilities to fill those jobs. But numerous scholarly critiques of the skills gap narrative note when employers say they can’t find workers to fill jobs, what is often happening is employers don’t want to pay wages attractive enough to recruit workers.9

In Kentucky, too many jobs do not pay a living wage. More than 1/3 of Kentucky’s working families have incomes below 200 percent of the poverty level, ranking Kentucky 17th worst in the nation on this measure in 2015.10 The median wage in Kentucky in 2016 was just $16.73 an hour, which means even a full-time, year-round worker made just $34,798 annually — not enough to support a “modest yet adequate” lifestyle for one adult and one dependent, even in rural Kentucky where the cost of living is lower.11 For these typical workers, with incomes in the middle of the wage distribution in the state, wages have hardly grown at all, once inflation is accounted for, over the last 15 years. Real wages for workers in the bottom three deciles are worse, for the most part, than they were in either 2007 or 2001.12

Meanwhile, worker benefits have been declining. The share of Kentucky workers with employer-sponsored health insurance is 54.5 percent, compared to 59.1 percent in 2007.13 In Kentucky, 48 percent of private sector workers ages 25 to 64 (approximately 566,780 Kentuckians) have an employer that does not offer a retirement plan. And just 68 percent of workers nationally have any paid sick leave.14 A survey of construction workers in 6 cities in the U.S. South found less than half (43 percent) are offered medical insurance by their employer, 80 percent lack a retirement plan and 78 percent lack paid sick time.15

To improve this bleak picture for workers and the resulting economic strain in our communities, Kentucky needs to enact a stronger minimum wage, overtime threshold and paid sick and family leave, for instance, and to protect access to Medicaid which covers many low-income workers. It also needs to focus on raising wages and benefits in specific sectors or occupations. For instance, a recent Working Poor Families Project report identifies a number of ways that states can improve the job quality for the early child care/education workforce.16

For the state to spend its workforce development funds well, it needs to focus efforts on cultivating high-quality jobs in our state. Yet it is clear from the data that job quality is not a top priority. Despite the claim that jobs in the 5 targeted sectors pay around $40,000 a year, the salaries Kentuckians should expect after completing short-term credentials — in advanced manufacturing, health care, construction, transportation/logistics and business/IT — may be overstated. Many jobs in the health care sector, particularly those for which the state is providing training, do not pay well. For instance, a nursing assistant makes around $25,000 a year.17 In addition, while welders in our state make an average of $32,000 or $39,000 depending on the job, entry-level wages are $23,000 and $26,000, respectively.18 And more generally, short-term credentials just do not have the return on investment that even an associate’s degree does.19

The federal Department of Education’s Gainful Employment data on 2014 graduates of some of the Kentucky programs that now qualify for the Work Ready Scholarship show they vary greatly in terms of earnings, with many earning low wages when they graduate.

The majority of job growth in Kentucky is in low-wage jobs. Eight of the 10 most common occupations in our state according to job projections through 2024 pay less than $15 an hour on average and 3 pay less than $10 an hour; just 2 of these 10 occupations require an associate’s degree or higher (registered nurses and general/operations managers).20 In Kentucky, 76.5 percent of jobs are in occupations that have median annual pay below 200 percent of the poverty level for a family of 4; Kentucky ranks 9th worst in the nation on that measure.21

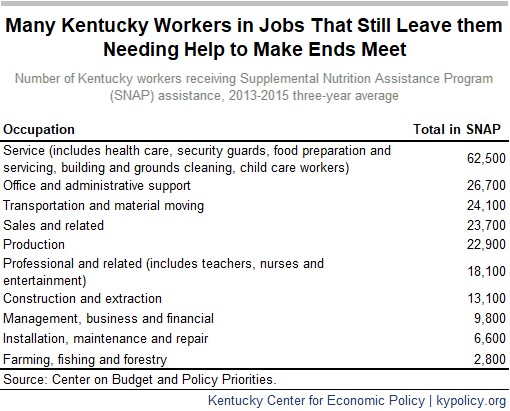

Even manufacturing jobs, which are widely considered to be good jobs, are now characterized by declining wages and working conditions.22 In fact, in Kentucky 28 percent of production workers’ families are enrolled in public safety net programs such as Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as “food stamps,” due to low wages.23

The table below shows the number of workers by industry in Kentucky whose incomes are low enough to receive SNAP. 24

The state’s five occupational areas of focus are all represented here.

Scheduling and Sick Leave

Relatively recent developments in job scheduling practices are contributing to very difficult working conditions for many. In addition, many jobs do not provide workers with any paid sick leave and may sanction workers who do not come to work when ill, even with a doctor’s note. These practices wreak havoc on workers’ lives, make it especially difficult for parents to hold jobs and contribute to turnover. State and federal workforce development dollars should not be used to support employers with these policies.

“Just-in-time” scheduling, for instance, is a practice employers use to more precisely match staff with consumer demand. For instance, if it is a slow week fewer staff will be allowed to work. This often leaves workers with little notice of their hours. On-call scheduling is a similar practice but provides even less notice, with workers learning the length of their schedule only hours before a shift starts. These scheduling methods make it impossible for workers to balance a job with other responsibilities such as arranging child care, taking classes or working another job to better make ends meet. Some of the consequences of these unstable hours are unpredictable earnings; negative health effects on workers and their families due to parental stress, psychological distress and inconsistent child care; and adverse impacts on child and adolescent development as parents find it difficult to adequately care for their children.25

At least 17 percent of the U.S. workforce has unstable work shift schedules — with at least 10 percent assigned to irregular and on-call work shift times and 7 percent working split shifts (when a work day is split into two or more parts) or rotating shifts (when a shift assignment — i.e., day or night shift — changes frequently, often on a weekly basis).26

While these scheduling practices are most often associated with low-wage retail and food service jobs, their reach is much greater. Low-level health care jobs are known to have unpredictable scheduling practices as well as other job quality issues. For instance, Certified Nurse Assistants (CNAs) earn low wages and often lack access to paid vacation or even sick days. One in-depth study found even in a high-end nursing home with much lower than average staff turnover (a potential indicator of higher job quality) — and where almost all beds are occupied all the time so the nursing home has the same number of staff each day — one out of three shifts was not according to schedule (either someone was working when they were not scheduled in advance to do so or someone was not working when the planned schedule had indicated they would be).27 Scheduling is particularly unpredictable for part-time workers, who typically want more hours. These jobs also often have high turnover.

In Kentucky’s current workforce development programs and partnerships, there is no transparency with regard to employers’ scheduling practices, and no criteria that businesses avoid harmful types of scheduling. In addition to the likelihood that targeted industries employ these practices, some state WIOA funds go to service sector jobs in which unfair scheduling practices are rampant. For instance, at least one of Kentucky’s Workforce Innovation Boards targets hospitality as a growing occupational area without consideration of the quality of these jobs.

Wage Theft

Wage theft, the failure to pay workers the full wages to which they are legally entitled, is also all too common. Among the forms wage theft can take are minimum wage violations, overtime violations, off-the-clock violations, meal break violations, pay stub and illegal deductions, tipped minimum wage violations (confiscating tips from workers or failing to pay tipped workers the difference between their tips and the legal minimum wage) and employee misclassification violations where employers wrongly classify workers as independent contractors to pay a wage lower than the legal minimum and avoid payroll compliance costs.28

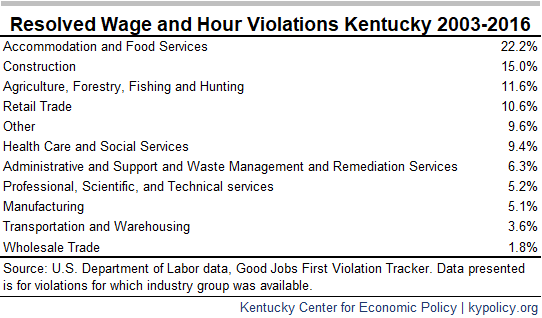

The U.S. Department of Labor’s (DOL) database of resolved wage and hour violation cases represent only a small portion of the actual violations that occur. At the same time federal labor protections have been eroding, the agency that enforces wage and hour laws has been stretched increasingly thin. In addition, filing a wage theft claim against an employer can be extremely difficult. Keeping in mind this is just the tip of the iceberg, between 2003 and 2016, the DOL penalized Kentucky employers with a total of $18.7 million in wage and hour violations.29

Construction and certain health care occupations (including home health) — two of the five industries Kentucky targets for workforce development — are among those with a high prevalence of wage theft nationally.30 According to one estimate, 26.4 percent of construction employers in Kentucky misclassify workers as independent contractors.31 As seen in the table below, in Kentucky between 2003 and 2016, 15 percent of resolved wage and hour violations were in construction, 9 percent were in health care and social services, 5 percent were in manufacturing and 4 percent were in transportation and warehousing.32

One study attempting to understand how prevalent workplace violations actually are, beyond what the DOL data reflects, found 1/4 of their sample (representing roughly the bottom 15 percent of the labor market in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles) had experienced a minimum wage violation in the previous work week — and among those who worked more than 40 hours a week, 70 percent had not been paid properly for their overtime work.33

Despite these all-too-common violations, criteria are not set forth in Kentucky’s workforce development policies and practices that would prevent public funds from going to violators, and information about partnering employers is not available to the public to track their violations.

Employee Turnover

Low-road jobs aren’t just bad for employees. They are also a poor investment for public training dollars. With poor wages and benefits, volatile scheduling practices and wage theft often lead to high turnover, which should be a concern when scarce workforce development funds are at stake. For instance, lack of access to paid sick leave contributes to turnover as workers lose their jobs when they are too sick to work or need to stay home to care for a sick child or aging parent. Workers may also quit because they can’t manage an illness in the family with a job that provides no paid sick time. Unpredictable scheduling also contributes to high turnover as workers leave to find a more stable work schedule or lose their jobs when they are unable to adjust to last-minute schedule changes.34

As noted in the report High Road WIOA: Building Higher Job Quality into Workforce Development, “When workers leave the jobs, training doesn’t pay off for the worker or for the workforce system — the investment is lost to the revolving door of turnover. In the worst case, businesses providing low-wage, revolving-door jobs may only be able to stay in business because of an effective subsidy from the workforce system to cover costs of worker recruitment and training.”35 An example given in the report is the common targeting by the workforce system of nursing assistant positions in long-term nursing care facilities. Short-term training can be geared to these job opportunities, but nursing home jobs often have high turnover as wages are limited and the stress and demands of the jobs very high.

In Wisconsin, where the state has begun requiring turnover information be reported, there are many nursing homes with annual turnover rates among nursing aides of over 50 percent and more than a few with turnover of 100 percent. However, there are quite a lot of nursing homes with turnover rates of less than 35 percent and a fair number with virtually no turnover, which shows turnover is not an inherent and unavoidable feature of nursing homes. When workers’ wages and working conditions meet higher standards they may stay for long periods of time in the same facility. As stated in the High Road report, “…there is no public purpose in investing public resources in nursing homes with turnover over 50%.” The report recommends investments in training only when nursing homes have annual turnover among full-time nursing assistants of 50 percent or less and turnover for part-timers of less than 110 percent.

Need for a High-Road Jobs Agenda for Kentucky

Our state’s workforce development system should do more to benefit both employers and workers over the longer term. A better investment of scarce state and federal funds is in high-quality jobs for Kentucky. Described in the High Road report as creating a “high road in workforce development,” this approach can help to make the state’s workforce system “an enduring force for better job quality.”36 With workers increasingly facing inadequate wages and benefits, often volatile, unpredictable scheduling practices and wage theft, these concerns should be central to our state’s workforce development agenda.

The following quality considerations could better guide Kentucky’s investments in workforce development.

Low Rates of Turnover

In order to invest in high-road jobs, Kentucky should set requirements for turnover rates for employers to qualify for workforce development funds. In doing so, the state should consider its unique circumstances and set thresholds based on industry conditions, among other factors. Incentivizing high-road employers that invest effort and resources in retaining employees is a strategy to create more high-quality jobs.

Adequate Wages and Benefits

It is similarly important that workforce development funds benefit employers offering decent wages and benefits. One possible threshold is a requirement that wages and benefits be at the top 20 percent for their industry and/or for the relevant occupation.37

Good Scheduling and Sick Time Practices

Our state should target its workforce development dollars to companies with better scheduling and sick time practices. Kentucky could require workforce resources go to employers that meet a family-friendly work time standard as well as a minimum paid sick leave standard. The High Road report gives as an example of a work time standard requiring that partnering employers post schedules at least two weeks in advance, practice standard scheduling (or a guarantee of a minimum number of hours if there are flexible schedules adjusted to accommodate employee as well as employer preferences/needs) and do not send employees home after they come to work when customer demand ends up being less than expected. A possible minimum paid sick leave standard is for employers to be required to provide at least 1 hour of accrued sick time for each 40 hours worked and to allow accrual of at least 6 days of paid leave that a worker can use when he/she is sick or needs to care for an ill child or other family/household member.

No Wage and Hour Violations

As noted in the High Road report, we should “not take for granted that every employer willing to engage with the state workforce development system has a strong commitment to worker development and training and plays by the rules when it comes to wage and hour laws.”

Given our workforce development funds are limited they should be spent where workers will get fair pay for fair work. Companies participating in wage theft should be disqualified from receiving workforce development funds.

While our state’s focus has been on credentialing communities and secondary school students as “ready to work,” Kentucky should consider a “good jobs certification” for Kentucky employers with high-road jobs practices along the lines outlined above. This certification could be used as a minimum qualification for workforce development funds and in other contexts as well. In several cities in Texas a “Better Builder” certification is being used to indicate a construction project meets certain minimum labor standards (including a living wage and safety training for workers), and in Austin an ordinance was passed to enable only projects that are Better Builder certified to have building permits expedited for large projects.38

As our state moves its workforce development strategy forward, high-road jobs need to be a central focus. Not only does this approach to workforce development in Kentucky make sense from worker and state investment perspectives, it is good for high-road employers who benefit from a highly skilled, stable workforce.39

-

John Schmitt and Janelle Jones, “Making Jobs Good,” Center for Economic and Policy Research, April 2013, http://cepr.net/documents/publications/good-jobs-policy-2013-04.pdf. John Schmitt and Janelle Jones, “Where Have All the Good Jobs Gone?,” Center for Economic and Policy Research, July 2012, http://cepr.net/publications/reports/where-have-all-the-good-jobs-gone. ↩

- These five areas were identified by the Kentucky Workforce Innovation Board and the Education and Workforce Development Cabinet. ↩

- Kentucky Education and Workforce Development Cabinet, “Work Ready Scholarship,” Budget Review Subcommittee on Education, July 27, 2017. ↩

- Kentucky Education and Workforce Development Cabinet, “Brief work Ready Skills Initiative Awards Summary,” Feb. 1, 2017. Kentucky Education and Workforce Development Cabinet, “Brief Work Ready Skills Initiative Round Two Award Summary,” May 18, 2017. ↩

- Kentucky Higher Education Assistance Authority, “2017-2018 Work Ready Kentucky Scholarship Listing of Approved Programs of Study,” https://www.kheaa.com/pdf/wrks_approved_programs.pdf. Students at for-profit colleges often have higher tuition than at many public institutions and have poorer student outcomes. Ashley Spalding, “Increasing Accountability of For-Profit Colleges,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Aug. 20, 2014, https://kypolicy.org/increasing-accountability-profit-colleges/. ↩

- Inflation-adjusted per-student state funding for higher education in Kentucky has been cut by 26.4 percent since 2008. Kenny Colston, “Kentucky Higher Ed Cuts Keep Kentucky Among Worst in Nation,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Aug. 23, 2017, https://kypolicy.org/higher-ed-cuts-keep-kentucky-among-worst-nation/. ↩

- Kentucky Workforce Innovation Board, “WIOA State Plan for the Commonwealth of Kentucky,” https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/osers/rsa/wioa/state-plans/ky.pdf. ↩

- “Kentucky Work Ready Communities,” Interim Joint Committee on Education, Oct. 9, 2017, http://workready.ky.gov/Downloadable/Resources/OutreachFlyer.pdf. ↩

- Peter Cappelli, Why Good People Can’t Get Jobs (Wharton Digital Press, 2012). Matthew Hora, Beyond the Skills Gap (Harvard Education Press, 2016). ↩

- Working Poor Families Project analysis of 2015 American Community Survey microdata. ↩

- Economic Policy Institute, “Family Budget Calculator,” http://www.epi.org/resources/budget/. ↩

- Anna Baumann, “Lack of Jobs and Wage Growth Still Hurts Kentuckians this Labor Day,” Sept. 1, 2017, https://kypolicy.org/lack-jobs-wage-growth-still-hurts-kentuckians-labor-day/. ↩

- Community Population Survey three-year estimates. ↩

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employee Benefits in the United States – March 2017,” July 2017, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/ebs2.pdf. ↩

- Nik Theodore, Bethany Boggess, Jackie Cornejo and Emily Timm, “Build a Better South,” Workers Defense Project, May 2017, http://www.workersdefense.org//www/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Build-a-Better-South-Full-Report-Digital.pdf. ↩

- Judy Berman and Melanie Kruvelis, “Improving Job Quality for the Early Childhood Workforce,” Working Poor Families Project, Fall 2017, http://www.workingpoorfamilies.org//www/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Fall-2017-WPFP-Policy-Brief_102317-.pdf. ↩

- Kentucky Center for Education and Workforce Statistics, “Kentucky Future Skill Report 2016,” https://kcews.ky.gov/Reports/TableauReport?url=https://kcewsreports.ky.gov/t/KCEWS/views/KentuckyFutureSkills2016/S_KFSR?:embed=y&:showShareOptions=true&:display_count=no&:showVizHome=no. ↩

- Kentucky Center for Education and Workforce Statistics, “2016 Statewide Employment and Wage Estimates,” https://kcews.ky.gov/KYLMI. ↩

- Christopher Jepsen, Kenneth Troske and Paul Coomes, “The Labor-Market Returns to Community College Degrees, Diplomas, and Certificates,” IZA, October 2012, http://ftp.iza.org/dp6902.pdf. ↩

- Jason Bailey, “Many Kentuckians Work in Bad Jobs,” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, Feb. 17, 2017, https://kypolicy.org/many-kentuckians-work-bad-jobs/. ↩

- Working Poor Families Project analysis of May 2015 Occupational Employment Statistics, Bureau of Labor Statistics, (http://www.bls.gov/oes/tables.htm. ↩

- Catherine Ruckelshaus and Sarah Leberstein, “Manufacturing Low Pay,” National Employment Law Project, November 2014, http://www.nelp.org/content/uploads/2015/03/Manufacturing-Low-Pay-Declining-Wages-Jobs-Built-Middle-Class.pdf. ↩

- Ken Jacobs, Zohar Perla, Ian Perry, and Dave Graham-Squire, “Producing Poverty: The Public Cost of Low-Wage Production Jobs in Manufacturing,” UC Berkeley Labor Center, May 2016, http://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/pdf/2016/Producing-Poverty.pdf. ↩

- Brynne Keith-Jennings, “Interactive Map: SNAP Helps Low-Wage Workers in Every State,” June 5, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/interactive-map-snap-helps-low-wage-workers-in-every-state. ↩

- Janelle Jones, “Working People Deserve Schedules that Work,” Economic Policy Institute,” June 20, 2017, http://www.epi.org/blog/working-people-deserve-schedules-that-work/. Leila Morsy and Richard Rothstein, “Parents’ Non-Standard Work Schedules Make Adequate Childrearing Difficult,” Aug. 6, 2015, http://www.epi.org/publication/parents-non-standard-work-schedules-make-adequate-childrearing-difficult-reforming-labor-market-practices-can-improve-childrens-cognitive-and-behavioral-outcomes/. ↩

- Lonnie Golden, “Irregular Work Scheduling and Its Consequences,” Economic Policy Institute, April 9, 2015, http://www.epi.org/publication/irregular-work-scheduling-and-its-consequences/. ↩

- Dan Clawson and Naomi Gerstel, Unequal Time: Gender, Class, and Family in Employment Schedules (Russell Sage Foundation, 2014). ↩

- David Cooper and Teresa Kroeger, “Employers Steal Billions from Worker Paychecks Each Year,” May 10, 2017, http://www.epi.org/publication/employers-steal-billions-from-workers-paychecks-each-year-survey-data-show-millions-of-workers-are-paid-less-than-the-minimum-wage-at-significant-cost-to-taxpayers-and-state-economies/. ↩

- Good Jobs First, “Violation Tracker,” https://www.goodjobsfirst.org/violation-tracker. ↩

- U.S. Department of Labor, “Low Wage, High Violation Industries,” https://www.dol.gov/whd/data/datatables.htm. ↩

- Ashley Spalding, “Misclassification Harms State Budget as Well as Workers,” Feb. 22, 2015, https://kypolicy.org/misclassification-harms-state-budget-well-workers/. ↩

- KCEP analysis of Good Jobs First Violation Tracker data, excluding wage and labor violations for which the occupational group was not available. ↩

- Ruth Milkman, “Estimating the Prevalence of Workplace Violations,” A Working Paper of the EINet Measurement Group, Sept. 2014, https://ssascholars.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/einet/files/einet_papers_milkman.pdf. ↩

- Jones, “Working People Deserve Schedules that Work.” ↩

- Laura Dresser, Hannah Halbert and Stephen Herzenberg, “High Road WIOA,” Economic Analysis Research Network, December 2015, https://www.keystoneresearch.org/sites/default/files/KRC_WIOA.pdf. ↩

- Dresser et al., “High Road WIOA.” ↩

- CLASP, “WIOA and Job Quality,” http://www.clasp.org/resources-and-publications/publication-1/WIOA-and-Job-Quality-memo.pdf ↩

- Better Builder, “Our Standards,” http://www.betterbuilder.org/better-builder-standards.html. ↩

- There are examples of successful companies like Costco that show the success of a high-road business model. Zeynep Ton, “Why Good Jobs Are Good for Retailers,” January-February 2012, https://hbr.org/2012/01/why-good-jobs-are-good-for-retailers. ↩