In recent weeks, important steps have been taken to address the public health crisis posed by incarceration in Kentucky’s jails and prisons during the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in historic declines in incarceration in county jails and some modest declines in prisons. Yet all Kentuckians deserve to be healthy and safe, and more progress is needed to limit the spread of the disease. This analysis looks at the significant progress that has been made so far and what more needs to be done.

Precautions such as frequent hand washing and social distancing are especially difficult in jails and prisons, making decarceration a critical component of the state’s public health strategy. Kentuckians who are incarcerated are at an increased risk for infection, and spread in the community in which the facility is located is also of concern. Many people – staff and those who are arrested and quickly released – move in and out of prisons and especially local jails on a daily basis. The issue has become even more pressing with the deaths of two individuals in a Kentucky prison due to COVID-19, and over 70 confirmed cases. Alarming reports of the virus spreading throughout facilities in other states add urgency to the situation. In a Marion, Ohio prison more than 80% of incarcerated individuals have tested positive for COVID-19, as have 160 corrections officers. The Cook County jail in Chicago is another example of a rapid outbreak of the virus that has already resulted in seven deaths.

Kentucky’s decarceration progress during COVID-19 is significant

Decarceration efforts in Kentucky amidst the COVID-19 public health crisis have occurred at both the state and local levels, resulting in a 29% decline in the number of people incarcerated in Kentucky’s county jails and a 4% decline in prisons (April 23 compared to March 12).

In order to discuss the progress that’s been made so far, and what remains to be done, it’s important to understand who is held in Kentucky’s jails and prisons. The more than 17,000 Kentuckians incarcerated in jails are either being held for counties while awaiting trial or serving relatively short misdemeanor sentences, in state custody serving lower-level (Class D or C) felony sentences, or held pretrial on federal charges through agreements with the U.S. Marshal’s Service (USMS) or U.S. Immigration and Customs (ICE). The approximately 11,700 individuals in the state’s prisons are serving sentences for higher-level felony convictions.

Here are the decarceration actions that have been taken so far:

- On March 22, Kentucky’s Chief Supreme Court Justice issued a statement instructing judges to reduce incarceration right away to avoid COVID-19 outbreaks in the state’s county jails. In the following weeks, judges, prosecutors and public defenders worked closely together in many counties to release people being held pretrial who were unable to afford bail as well as those serving sentences for misdemeanors.

- On April 2, Governor Beshear issued an executive order commuting the sentences of 186 people being held in jails or prisons for non-violent, non-sexual Class C or D felonies with less than five years left to serve who are “at higher risk for severe illness or death due to their medical conditions.”

- On April 14, the Kentucky Supreme Court issued an order (amended on April 23) temporarily requiring (through May 31) that most people who are arrested be administratively released so that fewer people will be incarcerated while awaiting trial. It also directs that individuals not be incarcerated for nonpayment of fines and fees, for failing to appear in court, or for nonpayment of child support or restitution.

- On April 24, Governor Beshear commuted the sentences of 352 additional people who were identified as being “particularly vulnerable to the effects of COVID-19 due to age and/or medical conditions” identified as serving sentences for non-violent, non-sexual offenses with fewer than five years remaining on their sentences.

The reduction in county-level incarceration in Kentucky has been significant since the court issued its first order to reduce incarceration in the context of COVID-19. The number of people in county custody (held pretrial and serving misdemeanor sentences) in local jails has plummeted by nearly 50%, from 11,500 people on March 12 to 5,916 on April 23. And the number of pretrial defendants in custody is the lowest it’s been in decades – a critical improvement that will result in fewer Kentuckians being put at risk of infection just because they can’t afford bail. As shown in the graph below based on an analysis by the Vera Institute, persistent jail overcrowding is also improving (although some individual jails remain over capacity).

Data is not available on the racial breakdown of releases, but a racial impact analysis should drive the conversation going forward. Black Kentuckians are overrepresented in the state’s jails and prisons, and COVID-19 has hospitalized and killed a disproportionate number of black Americans. A third of individuals incarcerated at Green River, where the virus has been spreading, are black. Decarceration efforts must seek to mitigate the devastating toll that structural racism is having on black Kentuckians in this public health crisis.

Majority of decarceration has been for people held in county custody

The graph below – based on an interactive dashboard produced by the Vera Institute – shows that the majority of decarceration in county jails this year has been for those held in county custody. The further reduction in the county jail population based on Governor Beshear’s April 24 commutation is not yet reflected in the data.

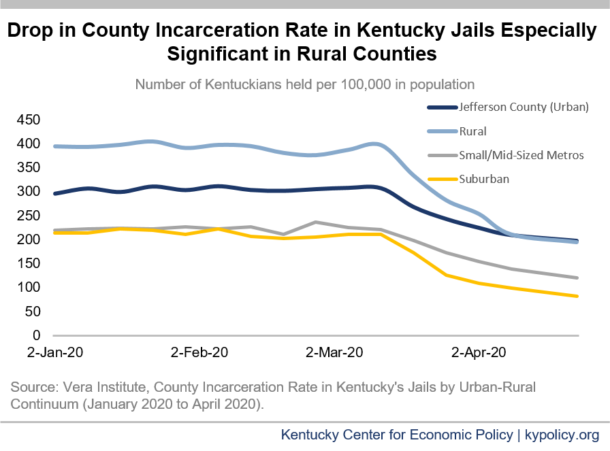

The overall decline of incarcerated individuals in county custody shown above has largely been driven by reductions in rural counties, where incarceration rates have historically been higher than those in urban areas. As a result, rural county-level incarceration rates are now in line with Jefferson County’s, as shown in the graph below based on an analysis by the Vera Institute (historically, the rural rates were about 33% higher than in Jefferson County).

As of April 23, 2020, 65% of people in Kentucky’s jails are now held for the state (55%) or federal (10%) government. As shown in the middle graphic above, the reduction of individuals in county jails who are held for the state has been much lower than the reduction in individuals held under county jurisdiction — a 13% drop between March 12 and April 23, compared to a 49% drop, respectively. The process for releasing people held by the state who have been convicted and sentenced is longer and more involved, requiring action in many cases by the governor or the parole board in conjunction with the Kentucky Department of Corrections. In addition, the state prison population has declined by approximately 500 individuals since mid-March, or 4%. Further action is therefore needed to release Kentuckians in state custody in both jails and prisons.

In recent weeks, the population of people held for the USMS and ICE has held steady at approximately 1,700 people. Some of the jails that remain overcrowded have high numbers of people held on federal detainers. For example, on April 23, the Grayson County Jail was at 128% of capacity, with 82% of the people being held in federal custody. In Crittenden County, the jail was at 109% of capacity, with people being held in federal custody making up 47% of the total population. And in Carter County, the jail was at 118% of capacity with 46% in federal custody. People held on federal detainers make up 28% of the overall jail population in the 19 counties that have agreements to hold them.

The pretrial release of federal detainees requires action by the court that ordered the person held, and the guidance provided by the U.S. Attorney General regarding COVID-19 release is changed little from pre -COVID-19 practices, making decarceration of this group of people based on federal action unlikely. However, because the relationship under which local jails incarcerate individuals in federal custody is contractual, local jails could further reduce their overall populations by refusing to accept additional federal detainers as Boone County recently did with regard to ICE detainers.

State needs to reduce incarceration and increase safety for those who remain behind bars

Kentucky’s progress in decarceration, especially in local jails, is significant and demonstrates the power of cooperative efforts in the pandemic. However, with more than 28,800 people still incarcerated in Kentucky jails and prisons during the COVID-19 pandemic there is more work to do, especially in terms of additional releases for individuals in state custody in jails and prisons.

Here are some additional actions that can be taken:

- The governor’s office should continue to review individuals serving felony sentences in prisons and jails, with additional commutations.

- The parole board should exercise its authority for releases by amending its eligibility policy on an emergency basis to allow for immediate parole consideration for some groups of incarcerated individuals and by automatically releasing others.

- Jails should reduce the number of, or stop accepting, individuals in federal custody.

- Data should be collected on the racial breakdown of decarceration efforts.

- The state needs to increase safety for those who remain incarcerated, including by testing staff and incarcerated people for infection on a widespread basis, providing sanitary masks to all, making soap and hand sanitizer readily available to all in every facility and enhancing cleaning/sanitizing practices in all facilities.

- More transparency around safety measures is needed in local jails.

Furthermore, people being released need transitional plans and support, as the many challenges associated with reentry into communities are made even more difficult during the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, the Justice Cabinet Secretary should pursue solutions for individuals who need new photo IDs to secure housing and employment when they leave jail. While this is not a new barrier to successful reentry, it is even more of a problem now because County Clerks offices are closed due to COVID-19.