Governor Bevin has said he will propose tax reform in a special session this year that will move Kentucky toward a “consumption-based” tax system – in other words shifting from income taxes to greater reliance on sales taxes. One of the options for doing so would be to expand the state’s sales tax base to include groceries. But a tax shift package that includes groceries would make Kentucky’s tax system more upside-down – asking more of those with less – and would further reduce our lagging rate of revenue growth, putting needed investments in our communities at even greater risk.

Repeal of Grocery Exemption Would Ask More of Low-to-Middle Income Families

Since 1972, Kentucky has exempted food purchased for home consumption from the sales tax at an estimated cost of $700 million in fiscal year 2017. 1 Food purchased in restaurants and “to-go” and “take-out” items are taxed.

Reapplying the sales tax to groceries would be highly regressive, meaning it would cost people with low incomes a much larger share of their income than wealthier people. That’s the case for two reasons. First, sales taxes themselves are regressive. In Kentucky, the poorest 20 percent pay 5.5 percent of their income in sales and excise taxes, while the richest 1 percent pay only 0.8 percent. 2 The reason for this disparity is that people with less income, out of necessity, typically spend most or all of their income to make ends meet. Those with higher incomes are able to save a portion of their earnings – and those savings are not subject to sales taxes.

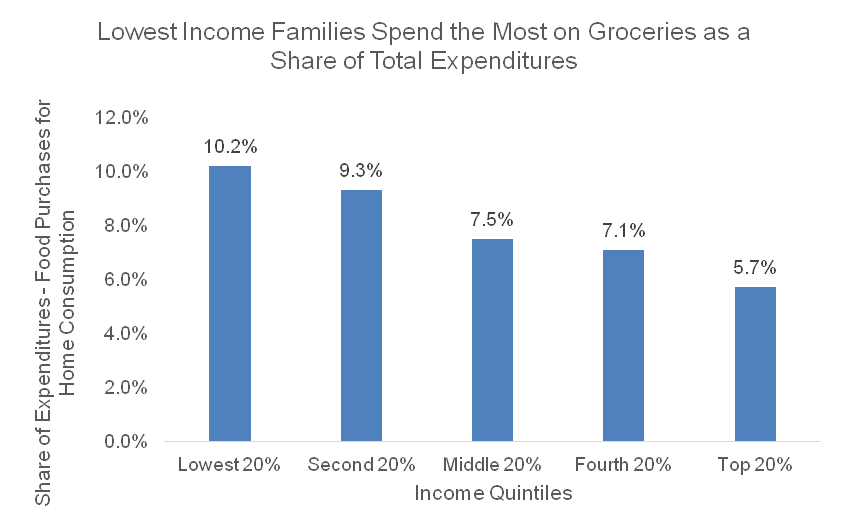

The second problem is that grocery taxes themselves are an especially regressive form of sales taxes. Rich or poor, everyone has to eat. Compared to other goods, there’s less a family can do – buying lower-priced items and less quantity – to cut grocery costs. Therefore, low-income families must devote a larger share of spending than those with higher incomes to meet this most basic need. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ annual Consumer Expenditure Survey show that food purchases for home consumption are a much larger share of total expenditures for the lowest income quintile than the top quintile (as shown in the graph below). 3 Also, it is notable that families in the lower income range spend a larger share of their total food budget on food to eat at home, while higher income households spend a larger share on eating meals out. 4

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

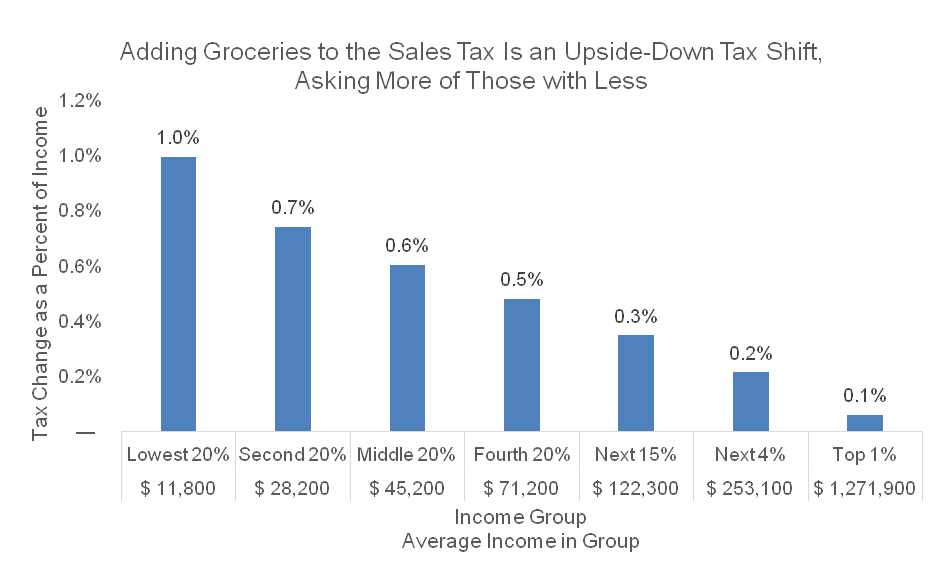

Lower-income families therefore receive the most benefit from the exemption for groceries. Repealing it would disproportionately increase the share of income they pay in taxes, making Kentucky’s tax system more regressive than it already is. 5 The chart below from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), illustrating the estimated distributional impact of including groceries in the Kentucky sales tax base, shows that families in the bottom 20 percent would see their taxes increase as a share of income by 10 times more than families in the top 1 percent. 6

Source: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP).

ITEP’s distributional analysis accounts for the fact that if groceries are taxed, some purchases made by low-income families through SNAP (formerly known as food stamps) would continue to be tax-free, as required by federal law. The impact on low-income families remains large however, for a couple of reasons. To begin with, not all low-income people are eligible for SNAP and some who are eligible do not claim it. For those who do, benefits are based on a formula that still expects people to contribute a significant portion of their income to food purchases – and those purchases outside of SNAP would become taxable under a repeal of the grocery exemption. 7 SNAP benefits are not intended to fully cover a family’s basic diet, providing only about $1.40 per person, per meal. The tax increase for families in the bottom quintile from putting the sales tax back on groceries equals $118 a year on average. 8

Low- to middle-income families’ purchasing power is already being squeezed. Real wages for Kentucky workers in the bottom 30 percent are below where they were 15 years ago and wages at the median have grown by less than 1 percent. 9 Meanwhile, income at the top has soared. Tax changes that ask more of those for whom the economy is stagnant – such as an expansion of sales taxes to groceries – exacerbate this inequality. For families in the second lowest income quintile, a grocery tax would increase what they pay by $197 on average every year. For families in the middle-income quintile, they would pay $271 more.

It should also be noted that if a grocery tax were part of a tax package that decreases income taxes, the extent to which it would deepen disparities in Kentucky’s tax system is even worse than indicated above. Currently in Kentucky, the poorest 20 percent pay 1.2 percent of their incomes in personal income taxes while the richest 1 percent pay 5 percent. 10 A plan that taxes groceries in order to pay for a cut in income tax rates would be a massive redistribution of dollars from low- and middle-income Kentuckians to those at the top.

Combined with Income Tax Cuts, Repeal Would Worsen Kentucky’s Revenue Problems

Adding groceries to the sales tax base would also worsen the extent to which Kentucky’s revenue keeps up with growth in the economy. The reason groceries weaken the rate of revenue growth is that they have been declining as a share of household expenditures for decades. Food costs have declined dramatically relative to the cost of other goods, families eat out more than they used to and other purchases associated with a service-oriented economy make up a larger share of consumption. Between 1960 and 2016, food purchased for off-premises consumption has fallen from 18.9 percent of what Americans buy to only 7.2 percent. 11 Since grocery consumption is a shrinking part of the economy, expanding the sales tax base to include it would lower the overall rate of sales tax revenue growth. Especially if a grocery tax is enacted along with a reduction in much faster-growing income taxes, such a plan would worsen Kentucky’s ability to maintain public investments over the long term. 12

Additionally, if Kentucky were to repeal the grocery exemption, shopping patterns in border communities could be impacted. While research does not support the claim that significant numbers of people relocate their entire lives to follow lower state income tax rates, it supports the concern that people who live in border areas – for instance in the greater Louisville and Cincinnati regions – would buy groceries across state lines. 13 Among our neighbors, Indiana, Ohio and West Virginia exempt groceries from sales taxes, with the rest taxing them at a lower rate than the general sales tax: Illinois at 1 percent; Missouri at 1.225 percent; Tennessee at 5 percent; and Virginia at 2.5 percent. 14 Changes in shopping patterns could reduce the anticipated state revenue from grocery sales taxes, as well as jobs in Kentucky and state and local revenue derived from Kentucky merchants’ income.

Kentucky Should Maintain Its Grocery Exemption

Of the 45 states that levy a sales tax, 31 exempt groceries from the base. For all the reasons this brief describes, the recent trend in state legislatures has been to reduce, rather than increase the sales tax on groceries. In our region alone over the last 20 years, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina and West Virginia have all exempted groceries from the sales tax; while Virginia, Tennessee and Arkansas have reduced their sales tax rates on groceries to below the general sales tax rate. 15

Taxing groceries won’t address the core problem with Kentucky’s tax system – that the revenue we have to invest in our communities is eroding relative to our economy. And the revenue a grocery tax would raise disproportionally impacts low-income families. Getting rid of special interest tax breaks for powerful interests and those with greater ability to pay is a better solution for Kentucky’s inadequate and upside-down tax system.

- Governor’s Office for Economic Analysis, “Commonwealth of Kentucky Tax Expenditure Analysis: Fiscal Years 2016-2018,” Office of the State Budget Director, http://osbd.ky.gov/Publications/Documents/Special%20Reports/Tax%20Expenditure%20Analysis%20Fiscal%20Years%202016-2018.pdf. This estimate includes the expenditures attributable to SNAP (formerly known as food stamp) purchases, which are exempt, and therefore overestimates the fiscal impact of a repeal. The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy estimates a $588 million impact from eliminating the grocery exemption. ↩

- Carl Davis, Kelly Davis, Matthew Gardner et al, “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States,” 5th Edition, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 2015, http://www.itep.org/whopays/. ↩

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Table 1101. Quintiles of income before taxes: annual expenditure means, shares, standard errors, and coefficients of variation,” Consumer Expenditure Survey, 2015, https://www.bls.gov/cex/2015/combined/quintile.pdf. ↩

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, “High-income households spent half of their food budget on food away from home in 2015,” TED: The Economics Daily, October 5, 2016, https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2016/high-income-households-spent-half-of-their-food-budget-on-food-away-from-home-in-2015.htm. ↩

- Currently in Kentucky, the top 1 percent of families pay 6 percent of their income in state and local taxes while the poorest 20 percent pay 9 percent. Carl Davis, Kelly Davis, Matthew Gardner et al, “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States.” ↩

- Some states that impose the sales tax on groceries attempt to address the disproportionate impact on low-income families by providing targeted income tax credits, usually in an amount that is much lower than what these families actually spend on groceries. Kentucky is better off maintaining its current exemption. In states that provide them, legislatures tend to let credits erode over time and even vote to cut them in times of fiscal strain. For instance, to help pay for income tax cuts for the wealthy in 2013, Kansas legislators voted to make their refundable credit for low-income families’ food purchases nonrefundable, which means that many low-income families with low or no income tax liability lost benefits. ↩

- SNAP’s net income calculation includes a handful of deductions (standard, dependent, medical expenses and high housing costs) that reduce the base of the expected contribution calculation. Even though this adjustment reflects the limited income families have available for food purchases, SNAP benefits still do not make up the entire gap between what families can spend, and what they need to become food-secure. Research suggests that higher benefits would result in higher spending on groceries. Patricia Anderson and Kristin Butcher, “The relationships Among SNAP Benefits, Grocery Spending, Diet Quality, and the Adequacy of Low-Income Families’ Resources,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 14, 2016, http://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-relationships-among-snap-benefits-grocery-spending-diet-quality-and-the. ↩

- The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “A Quick Guide to SNAP Eligibility and Benefits,” September 30, 2016, http://www.cbpp.org/research/a-quick-guide-to-snap-eligibility-and-benefits. ↩

- Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data, using CPI-U-RS to adjust for inflation. ↩

- Carl Davis, Kelly Davis, Matthew Gardner et al, “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States.” ↩

- KCEP analysis of Bureau of Economic Analysis personal consumption expenditure data. ↩

- Jason Bailey, “Will More Revenue from Tax Reform Be Real and Sustaining?” Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, February 9, 2017, https://kypolicy.org/will-revenue-tax-reform-real-sustaining/. ↩

- Michael Mazerov, “State Taxes Have a Negligible Impact on Americans’ Interstate Moves,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 21, 2014, http://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-taxes-have-a-negligible-impact-on-americans-interstate-moves. Mehmet Tosun and Mark Skidmore, “Cross-Border Shopping and the Sales Tax: A Reexamination of Food Purchases in West Virginia,” Working Paper 2005-07, Regional Research Institute, West Virginia University, http://rri.wvu.edu//www/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Tosunwp2005-7.pdf. ↩

- Eric Figueroa and Samantha Waxman, “Which States Tax the Sale of Food for Home Consumption in 2017?” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 1, 2017, http://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/which-states-tax-the-sale-of-food-for-home-consumption-in-2017. ↩

- Nicholas Johnson and Iris J. Lav, “Should States Tax Food? Examining the Policy Issues and Options,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 1998, http://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/stfdtax98.pdf. Eric Figueroa and Samantha Waxman, “Which States Tax the Sale of Food for Home Consumption in 2017.” ↩