Policies requiring Medicaid participants to report the number of hours they work in order to keep their health care are seeing renewed interest at both the state and federal level. But evidence shows clearly that such requirements are effective only at taking away health care and medicine, including from people who fulfill their requirements but get tripped up by complicated paperwork.

When people have Medicaid coverage stripped due to these onerous requirements they are left financially worse off with no improved employment outcomes. The more barriers that are put between Kentuckians and their health care, the more opportunities there are for people lose coverage. State and federal lawmakers should support the health and well-being of their constituents by removing as many barriers as possible, not adding additional paperwork hoops to jump through.

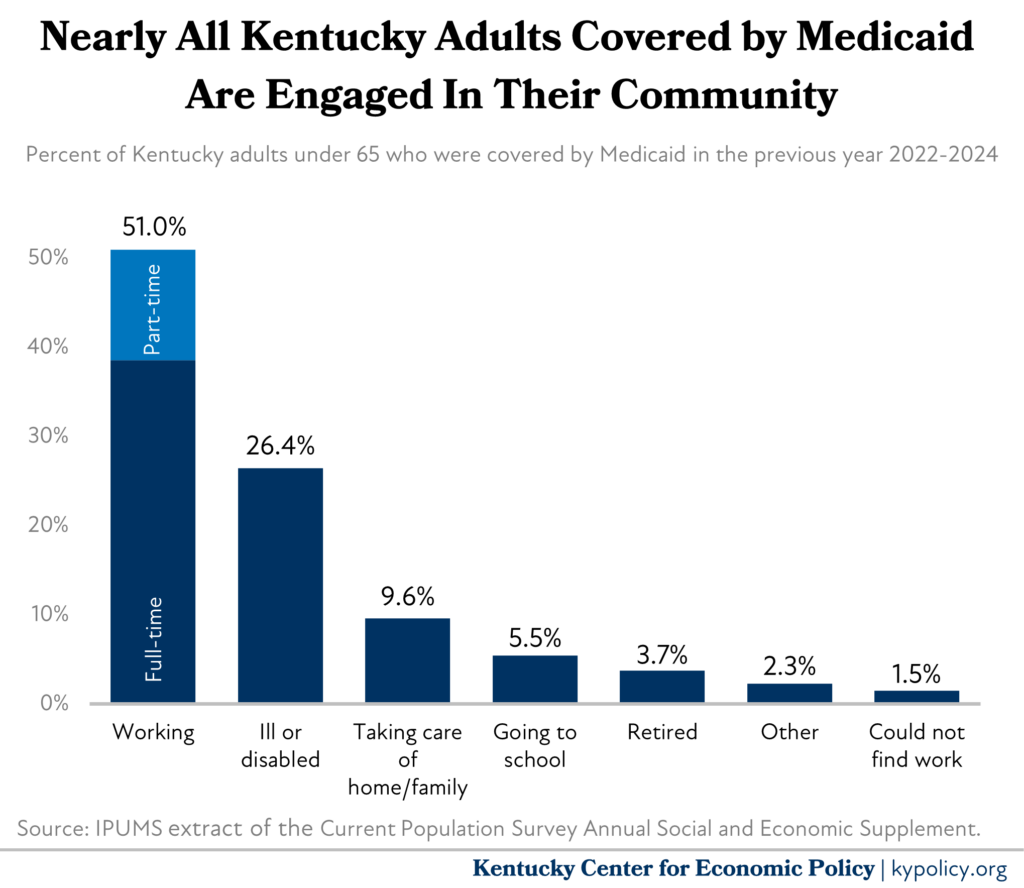

Nearly all Kentucky adults covered by Medicaid are already engaged in their community

According to census data, from 2022 to 2024, over half of Kentucky adults covered by Medicaid were working — 39% worked a full-time job and 12% worked a part-time job. And all of them, by definition, worked a job that paid so little, they qualified for Medicaid. Low-wage employment is inherently volatile, and creates significant challenges for workers trying to gain economic stability, which is a key reason why so many qualify for Medicaid to begin with. Workers in low-wage jobs tend to lack a normal number of hours per week, often experience last-minute cancelled or changed shifts, and are subject to “just-in-time” scheduling that could lead to being sent home early or called in last-minute. There is a strong correlation between increased instability at work inherent in low-wage jobs and increased turnover as well as increased hardship. Also, low-wage-earning workers are more often subject to company closures or position eliminations and wage stagnation or decline over time. The nature of low-wage work — which makes up a large portion of Kentucky’s economy particularly in rural and eastern parts of the state — results in a higher likelihood of being eligible for Medicaid.

While more than half of Kentucky adults covered by Medicaid are working, according to the same census data the vast majority of the remainder are ill or disabled (and therefore not likely subject to a work reporting requirement) or actively engaged in their community in some other way. Specifically, 21% are taking care of a loved one like a child or aging parent, attending school, retired, or looking for work. Only 2% of adults covered by Medicaid in Kentucky are not working for some reason the survey couldn’t identify. Presumably this small share is the fraction of Medicaid enrollees who are the target of any “community engagement” requirement. Many of those folks, however, may have been working recently, are dealing with challenges like homelessness, or other barriers that taking away healthcare would likely only worsen.

More paperwork barriers mean less enrollment

Past experience with reporting requirements shows that while most participants follow the requirement, it is the burden of proving it on a regular basis that results in disenrollment. This concept, sometimes called the “time tax,” is a well–documented means of reducing enrollment. A recent, national example is the 2023 unwinding of the Public Health Emergency, which required most Medicaid enrollees across the country to prove their eligibility for the first time in three years. This resulted in millions losing Medicaid, and up to 79% of the total disenrollments were due to paperwork errors rather than true verification of eligibility.

During the brief time when Arkansas had a work reporting requirement in 2018, only 371 of the 10,768 enrollees required to report work hours did so successfully, even though many met the requirements. Follow-up research two years later found that the work reporting requirement did not increase employment and left participants worse off financially, while 70% of Medicaid-eligible Arkansans did not know the policy was in effect. In Georgia, which currently has a work reporting requirement (which they were allowed to do legally only because it is the way they expanded eligibility to a new group of adults), only 4,231 of the estimated 240,485 uninsured adults were able to successfully navigate the requirements and become enrolled.

These kinds of requirements are also expensive to implement. Georgia’s program spent as much on technology improvements and administrative overhead as it did on actual care for enrollees during its first year and a half of implementation. When Kentucky proposed a similar requirement in 2016, it estimated that per-enrollee costs would actually increase under a requirement of this kind, despite leading to nearly 100,000 Kentuckians losing coverage from both the expansion and traditional Medicaid populations.

Work reporting requirements do nothing to improve employment, but would take away health care

A long history of rigorous research on work reporting requirements in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) shows that they have no meaningful effect on employment, but large, negative impacts on enrollment, including in Kentucky. Adults participating in SNAP, like those covered by Medicaid, are also largely employed, so it stands to reason that the threat of losing food assistance has little to do with whether or not they are working. Even if penalties or supports had some impact on a SNAP participant’s willingness to change their employment situation, past experience with extensive work supports showed that the degree to which a worker can do so is almost entirely dependent on the kinds of jobs available where they live.

While estimating the number of Kentuckians who would lose coverage is difficult without specific details of a work reporting requirement, there are 640,000 adults on Medicaid who could be at risk, including all 488,000 expansion-eligible adults and an additional 152,000 traditionally-eligible adults.